Sharia

|

|

This article needs attention from an expert in Islam. (January 2017) |

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

|

Texts and laws

|

| Part of the Politics series | ||||||||

| Basic forms of government | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power structure | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Power source | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Power ideology | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Politics portal | ||||||||

Sharia, Sharia law, or Islamic law (Arabic: شريعة (IPA: [ʃaˈriːʕa])) is the religious law forming part of the Islamic tradition.[1] It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam, particularly the Quran and the Hadith. In Arabic, the term sharīʿah refers to God's divine law and is contrasted with fiqh, which refers to its scholarly interpretations.[2][3][4] The manner of its application in modern times has been a subject of dispute between Muslim traditionalists and reformists.[1]

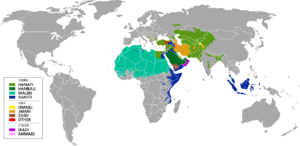

Traditional theory of Islamic jurisprudence recognizes four sources of sharia: the Quran, sunnah (authentic hadith), qiyas (analogical reasoning), and ijma (juridical consensus).[5] Different legal schools—of which the most prominent are Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi'i, Hanbali and Jafari—developed methodologies for deriving sharia rulings from scriptural sources using a process known as ijtihad.[2][3] Traditional jurisprudence distinguishes two principal branches of law, ʿibādāt (rituals) and muʿāmalāt (social relations), which together comprise a wide range of topics.[2][4] Its rulings assign actions to one of five categories: mandatory, recommended, permitted, abhorred, and prohibited.[2][3][4] Thus, some areas of sharia overlap with the Western notion of law while others correspond more broadly to following God's will.[3]

Historically, sharia was interpreted by independent jurists (muftis). Their legal opinions (fatwas) were taken into account by ruler-appointed judges who presided over qāḍī's courts, and by maẓālim courts, which were controlled by the ruler's council and administered criminal law.[2][3][4] Ottoman rulers achieved additional control over the legal system by promulgating their own legal code (qanun) and turning muftis into state employees.[3] Non-Muslim (dhimmi) communities had legal autonomy, except in cases of interconfessional disputes, which fell under jurisdiction of qadi's courts.[3]

In the modern era, sharia-based criminal laws were widely replaced by statutes inspired by European models.[3][6] Judicial procedures and legal education in the Muslim world were likewise brought in line with European practice.[3] While the constitutions of most Muslim-majority states contain references to sharia, its classical rules were largely retained only in personal status (family) laws.[3] Legislative bodies which codified these laws sought to modernize them without abandoning their foundations in traditional jurisprudence.[3][4] The Islamic revival of the late 20th century brought along calls by Islamist movements for full implementation of sharia, including reinstatement of hudud corporal punishments, such as stoning.[3][4] In some cases, this resulted in traditionalist legal reform,[note 1] while other countries witnessed juridical reinterpretation of sharia advocated by progressive reformers.[3][4]

The role of sharia has become a contested topic around the world. Attempts to impose it on non-Muslims have caused intercommunal violence in Nigeria[8][9] and may have contributed to the breakup of Sudan.[3] Some Muslim-minority countries in Asia (such as Israel[10]), Africa and Europe recognize the use of sharia-based family laws for their Muslim populations.[11][12] There are ongoing debates as to whether sharia is compatible with secular forms of government, human rights, freedom of thought, and women's rights.[13][14][15]

Contents

- 1 Etymology and usage

- 2 History

- 3 Definitions and disagreements

- 4 Application

- 5 Support and opposition

- 6 Criticism

- 7 Parallels with Western legal systems

- 8 See also

- 9 References

- 10 Further reading

- 11 External links

Etymology and usage[edit]

The primary range of meanings of the Arabic word šarīʿah, derived from the root š-r-ʕ, is related to religion and religious law.[16] It is used by Arabic-speaking peoples of the Middle East and designates a prophetic religion in its totality.[16] For example, sharīʿat Mūsā means law or religion of Moses and sharīʿatu-nā can mean "our religion" in reference to any monotheistic faith.[16] Within Islamic discourse, šarīʿah refers to religious regulations governing the lives of Muslims.[16] For many Muslims, the word means simply "justice", and they will consider any law that promotes justice and social welfare to conform to sharia.[3]

The lexicographical tradition records two major areas of use where the word šarīʿah can appear without religious connotation.[17] In texts evoking a pastoral or nomadic environment, the word and its derivatives refer to watering animals at a permanent water-hole or to the seashore, with special reference to animals who come there.[17] Another area of use relates to notions of stretched or lengthy.[17] This range of meanings is cognate with the Hebrew saraʿ and is likely to be the origin of the meaning "way" or "path".[17] Both these areas have been claimed to have given rise to aspects of the religious meaning.[17]

Some scholars describe the word šarīʿah as an archaic Arabic word denoting "pathway to be followed" (analogous to the Hebrew term Halakhah ["The Way to Go"]),[18] or "path to the water hole"[19][20] and argue that its adoption as a metaphor for a divinely ordained way of life arises from the importance of water in an arid desert environment.[20]

In the Quran, šarīʿah and its cognate širʿah occur once each, with the meaning "way" or "path".[16] The word šarīʿah was widely used by Arabic-speaking Jews during the middle ages, being the most common translation for the word torah in the 10th century Arabic Old Testament known as Saʿadya Gaon.[16] A similar use of the term can be found in Christian writers.[16] The Arabic expression Sharīʿat Allāh (شريعة الله "God’s Law") is a common translation for תורת אלוהים (‘God’s Law’ in Hebrew) and νόμος τοῦ θεοῦ (‘God’s Law’ in Greek in the New Testament [Rom. 7: 22]).[21] In Muslim literature, šarīʿah designates the laws or message of a prophet or God, in contrast to fiqh, which refers to a scholar's interpretation thereof.[22]

A related term al-qānūn al-islāmī (القانون الإسلامي, Islamic law), which was borrowed from European usage in the late 19th century, is used in the Muslim world to refer to a legal system in the context of a modern state.[23]

History[edit]

In Islam, the origin of sharia is the Qu'ran, and traditions gathered from the life of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad (born ca. 570 CE in Mecca).[24] The formative period of fiqh stretches back to the time of the early Muslim communities. In this period, jurists were more concerned with pragmatic issues of authority and teaching than with theory.[25]

Sharia underwent fundamental development, beginning with the reigns of caliphs Abu Bakr (632–34) and Umar (634–44) for Sunni Muslims, and Imam Ali for Shia Muslims, during which time many questions were brought to the attention of Muhammad's closest comrades for consultation.[26] During the reign of Muawiya b. Abu Sufyan ibn Harb, ca. 662 CE, Islam undertook an urban transformation, raising questions not originally covered by Islamic law.[26][page needed] The Umayyads initiated the office of appointing qadis, or Islamic judges. The jurisdiction of the qadi extended only to Muslims, while non-Muslim populations retained their own legal institutions.[27] Under the Umayyads Islamic scholars were "sidelined" from administration of justice and attempts to systematically uphold and develop Islamic law would wait for Abbasid rule.[citation needed] Al-Mansur (the first Abbasid caliph) felt a "pressing obligation—to make good on the promise to govern according to the sharia" and in 771 found "a respected member of the ulama" to serve as the head of the Egyptian judiciary, and to swear "to uphold the shari'a alone".[citation needed] The qadis were usually pious specialists in Islam. As these grew in number, they began to theorize and systemize Islamic jurisprudence.[28] The Abbasid made the institution of qadi independent from the government, but this separation wasn't always respected.[29]

Since then, changes in Islamic society have played an ongoing role in developing sharia, which branches out into fiqh and Qanun respectively. Progress in theory was started by 8th and 9th century Islamic scholars Abu Hanifa, Malik bin Anas, Al-Shafi'i, Ahmad ibn Hanbal and others.[30][31] Al-Shafi‘i is credited with deriving the theory of valid norms for sharia (uṣūl al-fiqh), arguing for a traditionalist, literal interpretation of Quran, Hadiths and methodology for law as revealed therein, to formulate sharia.[32][33]

A number of legal concepts and institutions were developed by Islamic jurists during the classical period of Islam, known as the Islamic Golden Age, dated from the 7th to 13th centuries. These shaped different versions of sharia in different schools of Islamic jurisprudence, called fiqhs.[34][35][36][37]

Both the Umayyad caliph Umar II and the Abbasids had agreed that the caliph could not legislate contrary to the Quran or the sunnah. Imam Shafi'i declared: "a tradition from the Prophet must be accepted as soon as it become known...If there has been an action on the part of a caliph, and a tradition from the Prophet to the contrary becomes known later, that action must be discarded in favor of the tradition from the Prophet." Thus, under the Abbasids the main features of sharia were definitively established and sharia was recognized as the law of behavior for Muslims.[38]

In modern times, the Muslim community has divided points of view: secularists believe that the law of the state should be based on secular principles, not on Islamic legal doctrines; traditionalists believe that the law of the state should be based on the traditional legal schools;[39] reformers believe that new Islamic legal theories can produce modernized Islamic law[40] and lead to acceptable opinions in areas such as women's rights.[41] This division persists until the present day.[42][43][44][45][46][47]

There has been a growing religious revival in Islam, beginning in the eighteenth century and continuing today. This movement has expressed itself in various forms ranging from wars to efforts towards improving education.[48][49]

Definitions and disagreements[edit]

Sharia, in its strictest definition, is a divine law, as expressed in the Quran and Muhammad's example (often called the sunnah). As such, it is related to but different from fiqh, which is emphasized as the human interpretation of the law.[50][51] Many scholars have pointed out that the sharia is not formally a code,[52] nor a well-defined set of rules.[53] The sharia is characterized as a discussion on the duties of Muslims[52] based on both the opinion of the Muslim community and extensive literature.[54] Hunt Janin and Andre Kahlmeyer thus conclude that the sharia is "long, diverse, and complicated."[53]

From the 9th century onward, the power to interpret law in traditional Islamic societies was in the hands of the scholars (ulema). This separation of powers served to limit the range of actions available to the ruler, who could not easily decree or reinterpret law independently and expect the continued support of the community.[55] Through succeeding centuries and empires, the balance between the ulema and the rulers shifted and reformed, but the balance of power was never decisively changed.[56] Over the course of many centuries, imperial, political and technological change, including the Industrial Revolution and the French Revolution, ushered in an era of European world hegemony that gradually included the domination of many of the lands which had previously been ruled by Islamic empires.[57][58] At the end of the Second World War, the European powers found themselves too weakened to maintain their empires as before.[59] The wide variety of forms of government, systems of law, attitudes toward modernity and interpretations of sharia are a result of the ensuing drives for independence and modernity in the Muslim world.[60][61]

According to Jan Michiel Otto, Professor of Law and Governance in Developing Countries at Leiden University, "[a]nthropological research shows that people in local communities often do not distinguish clearly whether and to what extent their norms and practices are based on local tradition, tribal custom, or religion. Those who adhere to a confrontational view of sharia tend to ascribe many undesirable practices to sharia and religion overlooking custom and culture, even if high-ranking religious authorities have stated the opposite."[62]

Sources of sharia law[edit]

According to human notions of sharia, there are two sources of sharia (understood as the divine law): the Quran and the Sunnah. The Quran is viewed as the unalterable word of God. It is considered in Islam to be an infallible part of sharia. The Quran covers a host of topics including God, personal laws for Muslim men and Muslim women, laws on community life, laws on expected interaction of Muslims with non-Muslims, apostates and ex-Muslims, laws on finance, morals, eschatology, and others.[63][page needed][64][page needed] The Sunnah is the life and example of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. The Sunnah's importance as a source of sharia, is confirmed by several verses of the Quran (e.g. [Quran 33:21]).[65] The Sunnah is primarily contained in the hadith or reports of Muhammad's sayings, his actions, his tacit approval of actions and his demeanor. While there is only one Quran, there are many compilations of hadith, with the most authentic ones forming during the sahih period (850 to 915 CE). The six acclaimed Sunni collections were compiled by (in order of decreasing importance) Muhammad al-Bukhari, Muslim ibn al-Hajjaj, Abu Dawood, Tirmidhi, Al-Nasa'i, Ibn Majah. The collections by al-Bukhari and Muslim, regarded the most authentic, contain about 7,000 and 12,000 hadiths respectively (although the majority of entries are repetitions). The hadiths have been evaluated on authenticity, usually by determining the reliability of the narrators that transmitted them.[66] For Shias, the Sunnah include life and sayings of The Twelve Imams.[67]

Quran versus Hadith[edit]

Muslims who reject the Hadith as a source of law, sometimes referred to as Quranists,[68][69] suggest that only laws derived exclusively from the Quran are valid.[70] They state that the hadiths in modern use are not explicitly mentioned in the Quran as a source of Islamic theology and practice, they were not recorded in written form until more than two centuries after the death of the prophet Muhammed.[68] They also state that the authenticity of the hadiths remains a question.[71][72]

The vast majority of Muslims, however, consider hadiths, which describe the words, conduct and example set by Muhammad during his life, as a source of law and religious authority second only to the Qur'an.[73] Similarly, most Islamic scholars believe both Quran and sahih hadiths to be a valid source of sharia, with Quranic verse 33.21, among others,[74][75] as justification for this belief.[69]

Ye have indeed in the Messenger of Allah a beautiful pattern (of conduct) for any one whose hope is in Allah and the Final Day, and who engages much in the Praise of Allah.

It is not fitting for a Believer, man or woman, when a matter has been decided by Allah and His Messenger to have any option about their decision: if any one disobeys Allah and His Messenger, he is indeed on a clearly wrong Path.

For vast majority of Muslims, sharia has historically been, and continues to be derived from both the Quran and the Hadiths.[69][73][75] The Sahih Hadiths of Sunni Muslims contain isnad, or a chain of guarantors reaching back to a companion of Muhammad who directly observed the words, conduct and example he set—thus providing the theological ground to consider the hadith to be a sound basis for sharia.[69][75] For Sunni Muslims, the musannaf in Sahih Bukhari and Sahih Muslim is most trusted and relied upon as source for Sunni sharia.[76] Shia Muslims, however, do not consider the chain of transmitters of Sunni hadiths as reliable, given these transmitters belonged to Sunni side in Sunni-Shia civil wars that followed after Muhammad's death.[77] Shia rely on their own chain of reliable guarantors, trusting compilations such as Kitab al-Kafi and Tahdhib al-Ahkam instead, and later hadiths (usually called akhbār by Shi'i).[78][79] The Shia version of hadiths contain the words, conduct and example set by Muhammad and Imams, which they consider as sinless, infallible and an essential source of sharia for Shi'ite Muslims.[77][80] However, in substance, the Shi'ite hadiths resemble the Sunni hadiths, with one difference—the Shia hadiths additionally include words and actions of its Imams (al-hadith al-walawi), the biological descendants of Muhammad, and these too are considered an important source for sharia by Shi'ites.[78][81]

Disagreements on Quran[edit]

Authenticity and writing of Quran[edit]

Some scholars such as John Wansbrough have challenged the authenticity of the Quran and whether it was written in the time of Muhammad.[82] In contrast, Estelle Whelan has refuted Wansbrough presenting evidence such as the inscriptions on the Dome of the Rock.[83][84] John Burton states that medieval era Islamic texts claiming the Quran was compiled after the death of Muhammad were forged to preserve the status-quo.[85] The final version of the Quran, states Burton, was compiled while Muhammad was still alive.[86] Most scholars accept that the Quran as is used for sharia, was compiled into the final current form during the caliphate of Uthman.[87][88]

Abrogation and textual inconsistencies[edit]

From the founding of Islam, the Muslim community has also debated the authenticity of compiled verses and the consistency within the Quran.[89][90] The inconsistencies in deriving sharia from the Quran were recognized and formally complicated by verses 2.106 and 16.101 of the Quran, which are known as the "verses of abrogation (Naskh)".[91]

The principle of abrogation has been historically accepted and applied by Islamic jurists on both the Quran and the Sunnah.[89][91] Sharia is thus determined through a chronological study of the primary sources, where older revelations are considered overruled by later revelations.[91][not in citation given][92] While historical and modern Islamic scholars have accepted the principle of abrogation for the Quran and the Sunnah, some modern scholars disagree that the principle of abrogation necessarily applies to the Quran.[93]

Islamic jurisprudence (Fiqh)[edit]

Fiqh (school of Islamic jurisprudence) represents the process of deducing and applying sharia principles, as well as the collective body of specific laws deduced from sharia using the fiqh methodology.[30] While Quran and Hadith sources are regarded as infallible, the fiqh standards may change in different contexts. Fiqh covers all aspects of law, including religious, civil, political, constitutional and procedural law.[94] Fiqh deploys the following to create Islamic laws:[30]

- Injunctions, revealed principles and interpretations of the Quran (Used by all schools and sects of Islam)

- Interpretation of the Sunnah (Muhammad's practices, opinions and traditions) and principles therein, after establishing the degree of reliability of hadith's chain of reporters (Used by all schools and sects of Islam)

If the above two sources do not provide guidance for an issue, then different fiqhs deploy the following in a hierarchical way:[30]

- Ijma, collective reasoning and consensus amongst authoritative Muslims of a particular generation, and its interpretation by Islamic scholars. This fiqh principle for sharia is derived from Quran 4:59.[95] Typically, the recorded consensus of Sahabah (Muhammad's companions) is considered authoritative and most trusted. If this is unavailable, then the recorded individual reasoning (Ijtihad) of Muhammad companions is sought. In Islam's history, some Muslim scholars have argued that Ijtihad allows individual reasoning of both the earliest generations of Muslims and later generation Muslims, while others have argued that Ijtihad allows individual reasoning of only the earliest generations of Muslims. (Used by all schools of Islam, Jafari fiqh accepts only Ijtihad of Shia Imams)[30][96]

- Qiyas, analogy is deployed if Ijma or historic collective reasoning on the issue is not available. Qiyas represents analogical deduction, the support for using it in fiqh is based on Quran 2:59, and this methodology was started by Abu Hanifa.[97] This principle is considered weak by Hanbali fiqh, and it usually avoids Qiyas for sharia. (Used by all Sunni schools of Islam, but rejected by Shia Jafari)[30]

- Istihsan, which is the principle of serving the interest of Islam and public as determined by Islamic jurists. This method is deployed if Ijtihad and Qiyas fail to provide guidance. It was started by Hanafi fiqh as a form of Ijtihad (individual reasoning). Maliki fiqh called it Masalih Al-Mursalah, or departure from strict adherence to the Texts for public welfare. The Hanbali fiqh called it Istislah and rejected it, as did Shafi'i fiqh. (Used by Hanafi, Maliki, but rejected by Shafii, Hanbali and Shia Jafari fiqhs)[30][32]

- Istihab and Urf which mean continuity of pre-Islamic customs and customary law. This is considered as the weakest principle, accepted by just two fiqhs, and even in them recognized only when the custom does not violate or contradict any Quran, Hadiths or other fiqh source. (Used by Hanafi, Maliki, but rejected by Shafii, Hanbali and Shia Jafari fiqhs)[30]

Schools of law[edit]

A Madhhab is a Muslim school of law that follows a fiqh (school of religious jurisprudence). In the first 150 years of Islam, there were many madhhab. Several of the Sahābah, or contemporary "companions" of Muhammad, are credited with founding their own. In the Sunni sect of Islam, the Islamic jurisprudence schools of Medina (Al-Hijaz, now in Saudi Arabia) created the Maliki madhhab, while those in Kufa (now in Iraq) created the Hanafi madhhab.[98] al-Shafi'i, who started as a student of Maliki school of Islamic law, and later was influenced by Hanafi school of Islamic law, disagreed with some of the discretion these schools gave to jurists, and founded the more conservative Shafi'i madhhab, which spread from jurisprudence schools in Baghdad (Iraq) and Cairo (Egypt).[99] Ahmad ibn Hanbal, a student of al-Shafi'i, went further in his criticism of Maliki and Hanafi fiqhs, criticizing the abuse and corruption of sharia from jurist discretion and consensus of later generation Muslims, and he founded the more strict, traditionalist Hanbali school of Islamic law.[100] Other schools such as the Jariri were established later, which eventually died out.[101]

Sunni sect of Islam has four major surviving schools of sharia: Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi'i, Hanbali; one minor school is named Ẓāhirī. Shii sect of Islam has three: Ja'fari (major), Zaydi and Ismaili.[42][45][102][103][104] There are other minority fiqhs as well, such as the Ibadi school of Khawarij sect, and those of Sufi and Ahmadi sects.[94][105] All Sunni and Shia schools of sharia rely first on the Quran and the sayings/practices of Muhammad in the Sunnah. Their differences lie in the procedure each uses to create Islam-compliant laws when those two sources do not provide guidance on a topic.[106] The Salafi movement creates sharia based on the Quran, Sunnah and the actions and sayings of the first three generations of Muslims.[107]

The Hanafi school spread with the patronage and military expansions led by Turkic Sultans and Ottoman Empire in West Asia, Southeast Europe, Central Asia and South Asia.[108][109] It is currently the largest madhhab of Sunni Muslims.[110] The Maliki school is predominantly found in West Africa, North Africa and parts of Arabia.[110] The Shafii school spread with patronage and military expansions led by maritime Sultans, and is mostly found in coastal regions of East Africa, Arabia, South Asia, Southeast Asia and islands in the Indian ocean.[111] The Hanbali school prevails in the smallest Sunni madhhab, predominantly found in the Arabian peninsula.[110] The Shiite Jafari school is mostly found in Persian region and parts of West Asia and South Asia.[citation needed]

Categories of law[edit]

Along with interpretation, each fiqh classifies its interpretation of sharia into one of the following five categories: fard (obligatory), mustahabb (recommended), mubah (neutral), makruh (discouraged), and haraam (forbidden). A Muslim is expected to adhere to that tenet of sharia accordingly.[112]

- Actions in the fard category are those mandatory on all Muslims. They include the five daily prayers, fasting, articles of faith, obligatory giving of zakat (charity, tax) to zakat collectors,[113][114] and the hajj pilgrimage to Mecca.[112]

- The mustahabb category includes proper behaviour in matters such as marriage, funeral rites and family life. As such, it covers many of the same areas as civil law in the West. Sharia courts attempt to reconcile parties to disputes in this area using the recommended behaviour as their guide. A person whose behaviour is not mustahabb can be ruled against by the judge.[115]

- Mubah category of behaviour is neither discouraged nor recommended, neither forbidden nor required; it is permissible.[112]

- Makruh behaviour, while it is not sinful of itself, is considered undesirable among Muslims. It may also make a Muslim liable to criminal penalties under certain circumstances.[115]

- Haraam behaviour is explicitly forbidden. It is both sinful and criminal. It includes all actions expressly forbidden in the Quran. Certain Muslim dietary and clothing restrictions also fall into this category.[112]

The recommended, neutral and discouraged categories are drawn largely from accounts of the life of Muhammad. To say a behaviour is sunnah is to say it is recommended as an example of the life and sayings of Muhammad. These categories form the basis for proper behaviour in matters such as courtesy and manners, interpersonal relations, generosity, personal habits and hygiene.[112]

Areas of Islamic law[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) |

|---|

| Islamic studies |

The areas of Islamic law include:[citation needed]

- Hygiene and purification laws, including the manner of cleansing, either wudhu or ghusl.

- Economic laws, including Zakāt, the annual almsgiving; Waqf, the religious endowment; the prohibition on interest or Riba; as well as inheritance laws.

- Dietary laws including Dhabihah, or ritual slaughter.

- Theological obligations, including the Hajj or pilgrimage, with its rituals such as Tawaf, Sa'yee and the Stoning of the Devil; salat, formal worship; Salat al-Janazah, the funeral prayer; and celebrating Eid al-Adha.

- Marital jurisprudence, including Nikah, the marriage contract; and divorce, known as Khula if initiated by a woman.

- Criminal jurisprudence, including Hudud, fixed punishments; Tazir, discretionary punishment; Qisas or retaliation; Diyya or blood money; and apostasy.

- Military jurisprudence, including jus in bello and casus belli; Hudna or truce; and rules regarding prisoners of war.

- Dress code, including hijab.

- Other topics include customs and behaviour, slavery and the status of non-Muslims.

- Other classifications

Shari'ah law has been grouped in different ways, such as:[116][117] Family relations, Crime and punishment, Inheritance and disposal of property, The economic system, External and other relations.[citation needed]

"Reliance of the Traveller", an English translation of a fourteenth-century CE reference on the Shafi'i school of fiqh written by Ahmad ibn Naqib al-Misri, organizes sharia law into the following topics: Purification, prayer, funeral prayer, taxes, fasting, pilgrimage, trade, inheritance, marriage, divorce and justice.[citation needed]

In some areas, there are substantial differences in the law between different schools of fiqh, countries, cultures and schools of thought.[citation needed]

Objectives of Islamic law[edit]

A number of scholars have advanced "objectives" (مقاصد maqaṣid al-Shariah also "goals" or "purposes") they believe the sharia is intended to achieve. Abu Hamid Al-Ghazali argued that they were the preservation of Islamic religion, and in the temporal world the protection of life, progeny, intellect and wealth of Muslims.[118][119] Yazid et al state that the objective of sharia in Islamic finance is to provide rules and regulations from the Quran and Sunnah.[120]

Application[edit]

Application by country[edit]

Most Muslim-majority countries incorporate sharia at some level in their legal framework, with many calling it the highest law or the source of law of the land in their constitution.[121][122] Most use sharia for personal law (marriage, divorce, domestic violence, child support, family law, inheritance and such matters).[123][124] Elements of sharia are present, to varying extents, in the criminal justice system of many Muslim-majority countries.[125] Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Brunei, Qatar, Pakistan, United Arab Emirates, Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, Sudan and Mauritania apply the code predominantly or entirely while it applies in some parts of Indonesia.[125][126]

Most Muslim-majority countries with sharia-prescribed hudud punishments in their legal code do not prescribe it routinely and use other punishments instead.[121][127] The harshest sharia penalties such as stoning, beheading and the death penalty are enforced with varying levels of consistency.[128]

Since the 1970s, most Muslim-majority countries have faced vociferous demands from their religious groups and political parties for immediate adoption of sharia as the sole, or at least primary legal framework.[129] Some moderates and liberal scholars within these Muslim countries have argued for limited expansion of sharia.[130]

With the growing Muslim immigrant communities in Europe, there have been reports in some media of "no-go zones" being established where sharia law reigns supreme.[131][132] However, there is no evidence of the existence of "no-go zones", and these allegations are sourced from anti-immigrant groups falsely equating low-income neighborhoods predominantly inhabited by immigrants as "no-go zones."[133][134]

In England, the Muslim Arbitration Tribunal makes use of sharia family law to settle disputes, and this limited adoption of sharia is controversial.[135][136][137]

Enforcement[edit]

Sharia is enforced in Islamic nations in a number of ways, including mutaween and hisbah.[citation needed]

The mutaween (Arabic: المطوعين، مطوعية muṭawwiʿīn, muṭawwiʿiyyah)[138] are the government-authorized or government-recognized religious police (or clerical police) of Saudi Arabia. Elsewhere, enforcement of Islamic values in accordance with sharia is the responsibility of Polisi Perda Syariah Islam in Aceh province of Indonesia,[139] Committee for the Propagation of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice (Gaza Strip) in parts of Palestine, and Basiji Force in Iran.[140]

Hisbah (Arabic: حسبة ḥisb(ah), or hisba) is a historic Islamic doctrine which means "accountability".[143] Hisbah doctrine holds that it is a religious obligation of every Muslim that he or she report to the ruler (Sultan, government authorities) any wrong behavior of a neighbor or relative that violates sharia or insults Islam. The doctrine states that it is the divinely sanctioned duty of the ruler to intervene when such charges are made, and coercively "command right and forbid wrong" in order to keep everything in order according to sharia.[144][145][146] Al-Jama'a al-Islamiyya (considered a terrorist organization) suggest that enforcement of sharia under the Hisbah doctrine is the sacred duty of all Muslims, not just rulers.[144] The doctrine of Hisbah in Islam has traditionally allowed any Muslim to accuse another Muslim, ex-Muslim or non-Muslim for beliefs or behavior that may harm Islamic society. This principle has been used in countries such as Egypt, Pakistan and others to bring blasphemy charges against apostates.[147] For example, in Egypt, sharia was enforced on the Muslim scholar Nasr Abu Zayd, through the doctrine of Hasbah, when he committed apostasy.[148][149] Similarly, in Nigeria, after twelve northern Muslim-majority states such as Kano adopted sharia-based penal code between 1999 and 2000, hisbah became the allowed method of sharia enforcement, where all Muslim citizens could police compliance of moral order based on sharia.[150] In Aceh province of Indonesia, Islamic vigilante activists have invoked Hasbah doctrine to enforce sharia on fellow Muslims as well as demanding non-Muslims to respect sharia.[151] Hisbah has been used in many Muslim majority countries, from Morocco to Egypt and in West Asia to enforce sharia restrictions on blasphemy and criticism of Islam over internet and social media.[152][153]

Legal and court proceedings[edit]

Sharia judicial proceedings have significant differences from other legal traditions, including those in both common law and civil law. Sharia courts traditionally do not rely on lawyers; plaintiffs and defendants represent themselves. Trials are conducted solely by the judge, and there is no jury system. There is no pre-trial discovery process, and no cross-examination of witnesses. Unlike common law, judges' verdicts do not set binding precedents[154][155] under the principle of stare decisis,[156] and unlike civil law, sharia is left to the interpretation in each case and has no formally codified universal statutes.[157]

The rules of evidence in sharia courts also maintain a distinctive custom of prioritizing oral testimony.[158] Witnesses, in a sharia court system, must be faithful, that is Muslim.[159] Male Muslim witnesses are deemed more reliable than female Muslim witnesses, and non-Muslim witnesses considered unreliable and receive no priority in a sharia court.[160][161] In civil cases in some countries, a Muslim woman witness is considered half the worth and reliability than a Muslim man witness.[162][163] In criminal cases, women witnesses are unacceptable in stricter, traditional interpretations of sharia, such as those found in Hanbali madhhab.[159]

Criminal cases[edit]

A confession, an oath, or the oral testimony of Muslim witnesses are the main evidence admissible, in sharia courts, for hudud crimes, that is the religious crimes of adultery, fornication, rape, accusing someone of illicit sex but failing to prove it, apostasy, drinking intoxicants and theft.[164][165][166][167] Testimony must be from at least two free Muslim male witnesses, or one Muslim male and two Muslim females, who are not related parties and who are of sound mind and reliable character. Testimony to establish the crime of adultery, fornication or rape must be from four Muslim male witnesses, with some fiqhs allowing substitution of up to three male with six female witnesses; however, at least one must be a Muslim male.[168] Forensic evidence (i.e., fingerprints, ballistics, blood samples, DNA etc.) and other circumstantial evidence is likewise rejected in hudud cases in favor of eyewitnesses, a practice which can cause severe difficulties for women plaintiffs in rape cases.[169][170]

Muslim jurists have debated whether and when coerced confession and coerced witnesses are acceptable.[citation needed] In the Ottoman Criminal Code, the executive officials were allowed to use torture only if the accused had a bad reputation and there were already indications of his guilt, such as when stolen goods were found in his house, if he was accused of grievous bodily harm by the victim or if a criminal during investigation mentioned him as an accomplice.[171] Confessions obtained under torture could not be used as a ground for awarding punishment unless they were corroborated by circumstantial evidence.[171]

Civil cases[edit]

Quran 2:282 recommends written financial contracts with reliable witnesses, although there is dispute about equality of female testimony.[163]

Marriage is solemnized as a written financial contract, in the presence of two Muslim male witnesses, and it includes a brideprice (Mahr) payable from a Muslim man to a Muslim woman. The brideprice is considered by a sharia court as a form of debt. Written contracts are paramount, in sharia courts, in the matters of dispute that are debt-related, which includes marriage contracts.[172] Written contracts in debt-related cases, when notarized by a judge, is deemed more reliable.[173]

In commercial and civil contracts, such as those relating to exchange of merchandise, agreement to supply or purchase goods or property, and others, oral contracts and the testimony of Muslim witnesses triumph over written contracts. Sharia system has held that written commercial contracts may be forged.[173][174] Timur Kuran states that the treatment of written evidence in religious courts in Islamic regions created an incentive for opaque transactions, and the avoidance of written contracts in economic relations. This led to a continuation of a "largely oral contracting culture" in Muslim nations and communities.[174][175]

In lieu of written evidence, oaths are accorded much greater weight; rather than being used simply to guarantee the truth of ensuing testimony, they are themselves used as evidence. Plaintiffs lacking other evidence to support their claims may demand that defendants take an oath swearing their innocence, refusal thereof can result in a verdict for the plaintiff.[176] Taking an oath for Muslims can be a grave act; one study of courts in Morocco found that lying litigants would often "maintain their testimony 'right up to the moment of oath-taking and then to stop, refuse the oath, and surrender the case."[177] Accordingly, defendants are not routinely required to swear before testifying, which would risk casually profaning the Quran should the defendant commit perjury;[177] instead oaths are a solemn procedure performed as a final part of the evidence process.[citation needed]

Sentencing[edit]

Sharia courts treat women and men differently, with Muslim woman's life and blood-money compensation sentence (Diyya) as half as that of a Muslim man's life.[178][179] Sharia also treats Muslims and non-Muslims differently in the sentencing process.[180] Human Rights Watch and United States' Religious Freedom Report states that in sharia courts of Saudi Arabia, "The calculation of accidental death or injury compensation is discriminatory. In the event a court renders a judgment in favor of a plaintiff who is a Jewish or Christian male, the plaintiff is only entitled to receive 50 percent of the compensation a Muslim male would receive; all other non-Muslims [Buddhists, Hindus, Jains, Atheists] are only entitled to receive one-sixteenth of the amount a male Muslim would receive".[181][182][183]

Saudi Arabia follows the Hanbali madhab, whose historic jurisprudence texts considered a Christian or Jew life as half the worth of a Muslim. Jurists of other schools of law in Islam have ruled differently. For example, Shafi'i sharia considers a Christian or Jew life as a third the worth of a Muslim, and Maliki's sharia considers it worth half.[180] The legal schools of Hanafi, Maliki and Shafi'i Sunni Islam as well as those of twelver Shia Islam have considered the life of polytheists and atheists as one-fifteenth the value of a Muslim during sentencing.[180]

Support and opposition[edit]

Support[edit]

A 2013 survey based on interviews of 38,000 Muslims, randomly selected from urban and rural parts in 39 countries using area probability designs, by the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life found that a majority—in some cases "overwhelming" majority—of Muslims in a number of countries support making sharia the law of the land, including Afghanistan (99%), Iraq (91%), Niger (86%), Malaysia (86%), Pakistan (84%), Morocco (83%), Bangladesh (82%), Egypt (74%), Indonesia (72%), Jordan (71%), Uganda (66%), Ethiopia (65%), Mali (63%), Ghana (58%), and Tunisia (56%).[184] In Muslim regions of Southern-Eastern Europe and Central Asia, the support is less than 50%: Russia (42%), Kyrgyzstan (35%), Tajikistan (27%), Kosovo (20%), Albania (12%), Turkey (12%), Kazakhstan (10%), Azerbaijan (8%). Regarding specific averages, in South Asia, Sharia had 84% favorability rating among the respondents; In Southeast Asia 77%; In the Middle-East/North Africa 74%; In Sub-Saharan Africa 64%; In Southern-Eastern Europe 18%; And in Central Asia 12%.[184]

However, while most of those who support implementation of sharia favor using it in family and property disputes, fewer supported application of severe punishments such as whippings and cutting off hands, and interpretations of some aspects differed widely.[184]

According to the Pew poll, among Muslims who support making sharia the law of the land, most do not believe that it should be applied to non-Muslims. In the Muslim-majority countries surveyed this proportion varied between 74% (of 74% in Egypt) and 19% (of 10% in Kazakhstan), as percentage of those who favored making sharia the law of the land.[185]

Polls demonstrate that for Egyptians, the 'Shariah' is associated with notions of political, social and gender justice.[186]

In 2008, Rowan Williams, the archbishop of Canterbury, has suggested that Islamic and Orthodox Jewish courts should be integrated into the British legal system alongside ecclesiastical courts to handle marriage and divorce, subject to agreement of all parties and strict requirements for protection of equal rights for women.[187] His reference to the sharia sparked a controversy.[187] Later that year, Nicholas Phillips, then Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales, stated that there was "no reason why sharia principles [...] should not be the basis for mediation or other forms of alternative dispute resolution."[188]

A 2008 YouGov poll in the United Kingdom found 40% of Muslim students interviewed supported the introduction of sharia into British law for Muslims.[189]

Since the 1970s, Islamist movements whose goals are establishment of Islamic states and implementation of sharia have become prominent in some countries.[citation needed]

Extremism[edit]

Fundamentalists, wishing to return to basic Islamic religious values and law, have in some instances imposed harsh sharia punishments for crimes, curtailed civil rights and violated human rights. Extremists have used the Quran and their own particular version of sharia to justify acts of war and terror against Muslim as well as non-Muslim individuals and governments, using alternate, conflicting interpretations of sharia and their notions of jihad.[190][191][192]

The sharia basis of arguments advocating terrorism is controversial. According to Bernard Lewis, "[a]t no time did the classical jurists offer any approval or legitimacy to what we nowadays call terrorism"[193] and the terrorist practice of suicide bombing "has no justification in terms of Islamic theology, law or tradition".[194] In the modern era the notion of jihad has lost its jurisprudential relevance and instead gave rise to an ideological and political discourse.[195] For al-Qaeda ideologues, in jihad all means are legitimate, including targeting Muslim non-combatants and the mass killing of non-Muslim civilians.[190] According to these interpretations, Islam does not discriminate between military and civilian targets, but rather between Muslims and nonbelievers, whose blood can be legitimately spilled.[190]

Some scholars of Islam, such as Yusuf al-Qaradawi and Sulaiman Al-Alwan, have supported suicide attacks against Israeli civilians, arguing that they are army reservists and hence should be considered as soldiers, while Hamid bin Abdallah al-Ali declared that suicide attacks in Chechnya were justified as a "sacrifice".[190][196] Many prominent Islamic scholars, including al-Qaradawi himself, have issued condemnations of terrorism in general terms.[197] For example, Abdul-Aziz ibn Abdullah Al ash-Sheikh, the Grand Mufti of Saudi Arabia has stated that "terrorizing innocent people [...] constitute[s] a form of injustice that cannot be tolerated by Islam", while Muhammad Sayyid Tantawy, Grand Imam of al-Azhar and former Grand Mufti of Egypt has stated that "attacking innocent people is not courageous; it is stupid and will be punished on the Day of Judgment".[190][198]

Opposition[edit]

In the post-9/11 non-Muslim Western world, sharia has been called a source of "hysteria",[199] "more controversial than ever", the one aspect of Islam that inspires "particular dread".[200] On the Internet, "dozens of self-styled `counter-jihadis`" emerged to campaign against sharia law, describing it in strict interpretations resembling those of Salafi Muslims.[200] Several years after 9/11, fear of sharia law and of "the ideology of extremism" among Muslims reportedly spread to mainstream conservative Republicans in the United States.[201] Former House Speaker Newt Gingrich won ovations calling for a federal ban on sharia law.[201] In 2015, the governor of Louisiana (Bobby Jindal) warned of the danger of purported "no-go zones" in European cities allegedly operating under sharia law and where local laws are not applicable.[202] The issue of "liberty versus Sharia" was called a "momentous civilizational debate" in at least one conservative editorial page.[203] In 2008 in Britain, the future Prime Minister (David Cameron) declared his opposition to "any expansion of Sharia law in the UK."[204] In Germany, in 2014, the Interior Minister (Thomas de Maizière) told a newspaper (Bild), "Sharia law is not tolerated on German soil."[205]

In the U.S., opponents of Sharia have sought to ban it from being considered in courts, where it has been routinely used alongside traditional Jewish and Catholic laws to decide legal, business, and family disputes subject to contracts drafted with reference to such laws, as long as they do not violate secular law or the U.S. constitution.[206] After failing to gather support for a federal law making observing Sharia a felony punishable by up to 20 years in prison, anti-Sharia activists have focused on state legislatures.[206] By 2014, bills aimed against use of Sharia have been introduced in 34 states and passed in 11.[206] These bills have generally referred to banning foreign or religious law in order to thwart legal challenges.[206]

Criticism[edit]

Compatibility with democracy[edit]

Ali Khan states that "constitutional orders founded on the principles of sharia are fully compatible with democracy, provided that religious minorities are protected and the incumbent Islamic leadership remains committed to the right to recall".[207][208] Other scholars say sharia is not compatible with democracy, particularly where the country's constitution demands separation of religion and the democratic state.[209][210]

Courts in non-Muslim majority nations have generally ruled against the implementation of sharia, both in jurisprudence and within a community context, based on sharia's religious background. In Muslim nations, sharia has wide support with some exceptions.[211] For example, in 1998 the Constitutional Court of Turkey banned and dissolved Turkey's Refah Party on the grounds that "Democracy is the antithesis of Sharia", the latter of which Refah sought to introduce.[212][213]

On appeal by Refah the European Court of Human Rights determined that "sharia is incompatible with the fundamental principles of democracy".[214][215][216] Refah's sharia-based notion of a "plurality of legal systems, grounded on religion" was ruled to contravene the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms. It was determined that it would "do away with the State's role as the guarantor of individual rights and freedoms" and "infringe the principle of non-discrimination between individuals as regards their enjoyment of public freedoms, which is one of the fundamental principles of democracy".[217]

Human rights[edit]

Several major, predominantly Muslim countries have criticized the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) for its perceived failure to take into account the cultural and religious context of non-Western countries. Iran declared in the UN assembly that UDHR was "a secular understanding of the Judeo-Christian tradition", which could not be implemented by Muslims without trespassing the Islamic law.[218] Islamic scholars and Islamist political parties consider 'universal human rights' arguments as imposition of a non-Muslim culture on Muslim people, a disrespect of customary cultural practices and of Islam.[219][220] In 1990, the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, a group representing all Muslim majority nations, met in Cairo to respond to the UDHR, then adopted the Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam.[221][222]

Ann Elizabeth Mayer points to notable absences from the Cairo Declaration: provisions for democratic principles, protection for religious freedom, freedom of association and freedom of the press, as well as equality in rights and equal protection under the law. Article 24 of the Cairo declaration states that "all the rights and freedoms stipulated in this Declaration are subject to the Islamic shari'a".[223]

In 2009, the journal Free Inquiry summarized the criticism of the Cairo Declaration in an editorial: "We are deeply concerned with the changes to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by a coalition of Islamic states within the United Nations that wishes to prohibit any criticism of religion and would thus protect Islam's limited view of human rights. In view of the conditions inside the Islamic Republic of Iran, Egypt, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, the Sudan, Syria, Bangladesh, Iraq, and Afghanistan, we should expect that at the top of their human rights agenda would be to rectify the legal inequality of women, the suppression of political dissent, the curtailment of free expression, the persecution of ethnic minorities and religious dissenters – in short, protecting their citizens from egregious human rights violations. Instead, they are worrying about protecting Islam."[224]

H. Patrick Glenn states that sharia is structured around the concept of mutual obligations of a collective, and it considers individual human rights as potentially disruptive and unnecessary to its revealed code of mutual obligations. In giving priority to this religious collective rather than individual liberty, the Islamic law justifies the formal inequality of individuals (women, non-Islamic people).[225] Bassam Tibi states that sharia framework and human rights are incompatible.[226] Abdel al-Hakeem Carney, in contrast, states that sharia is misunderstood from a failure to distinguish sharia from siyasah (politics).[227]

Freedom of speech[edit]

The Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam conditions free speech with sharia law: Article 22(a) of the Declaration states that "Everyone shall have the right to express his opinion freely in such manner as would not be contrary to the principles of the Shariah."[228]

Blasphemy in Islam is any form of cursing, questioning or annoying God, Muhammad or anything considered sacred in Islam.[229][230][231][232] The sharia of various Islamic schools of jurisprudence specify different punishment for blasphemy against Islam, by Muslims and non-Muslims, ranging from imprisonment, fines, flogging, amputation, hanging, or beheading.[229][233][234][235] In some cases, sharia allows non-Muslims to escape death by converting and becoming a devout follower of Islam.[236]

Blasphemy, as interpreted under sharia, is controversial.[237] Muslim nations have petitioned the United Nations to limit "freedom of speech" because "unrestricted and disrespectful opinion against Islam creates hatred".[238] Other nations, in contrast, consider blasphemy laws as violation of "freedom of speech",[239] stating that freedom of expression is essential to empowering both Muslims and non-Muslims, and point to the abuse of blasphemy laws, where hundreds, often members of religious minorities, are being lynched, killed and incarcerated in Muslim nations, on flimsy accusations of insulting Islam.[240][241]

Freedom of thought, conscience and religion[edit]

According to the United Nations' Universal Declaration of Human Rights, every human has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change their religion or belief. Sharia has been criticized for not recognizing this human right. According to scholars[13][242][243] of Islamic law, the applicable rules for religious conversion under sharia are as follows:

- If a person converts to Islam, or is born and raised as a Muslim, then he or she will have full rights of citizenship in an Islamic state.[13]

- Leaving Islam is a sin and a religious crime. Once any man or woman is officially classified as Muslim, because of birth or religious conversion, he or she will be subject to the death penalty if he or she becomes an apostate, that is, abandons his or her faith in Islam in order to become an atheist, agnostic or to convert to another religion. Before executing the death penalty, sharia demands that the individual be offered one chance to return to Islam.[13]

- If a person has never been a Muslim, and is not a kafir (infidel, unbeliever), he or she can live in an Islamic state by accepting to be a dhimmi, or under a special permission called aman. As a dhimmi or under aman, he or she will suffer certain limitations of rights as a subject of an Islamic state, and will not enjoy complete legal equality with Muslims.[13]

- If a person has never been a Muslim, and is a kafir (infidel, unbeliever), sharia demands that he or she should be offered the choice to convert to Islam and become a Muslim; if he or she rejects the offer, he or she may become a dhimmi. Failure to pay the tax may lead the non-muslim to either be enslaved, killed or ransomed if captured.[13]

According to sharia theory, conversion of disbelievers and non-Muslims to Islam is encouraged as a religious duty for all Muslims, and leaving Islam (apostasy), expressing contempt for Islam (blasphemy), and religious conversion of Muslims is prohibited.[244][245] Not all Islamic scholars agree with this interpretation of sharia theory. In practice, as of 2011, 20 Islamic nations had laws declaring apostasy from Islam as illegal and a criminal offense. Such laws are incompatible with the UDHR's requirement of freedom of thought, conscience and religion.[246][247][248][249] In another 2013 report based on international survey of religious attitudes, more than 50% of Muslim population in 6 out of 49 Islamic countries supported death penalty for any Muslim who leaves Islam (apostasy).[250][251] However it is also shown that the majority of Muslims in the 43 nations surveyed did not agree with this interpretation of sharia.

Some scholars claim sharia allows religious freedom because a sharia verse teaches, "there is no compulsion in religion."[252] Other scholars claim sharia recognizes only one proper religion, considers apostasy as sin punishable with death, and members of other religions as kafir (infidel);[253] or hold that sharia demands that all apostates and kafir must be put to death, enslaved or be ransomed.[254][need quotation to verify][255][256][257] Yet other scholars suggest that sharia has become a product of human interpretation and inevitably leads to disagreements about the “precise contents of the Shari'a." In the end, then, what is being applied is not sharia, but what a particular group of clerics and government decide is sharia. It is these differing interpretations of sharia that explain why many Islamic countries have laws that restrict and criminalize apostasy, proselytism and their citizens' freedom of conscience and religion.[258][259]

LGBT rights[edit]

Homosexual intercourse is illegal under sharia law, though the prescribed penalties differ from one school of jurisprudence to another. For example, some Muslim-majority countries impose the death penalty for acts perceived as sodomy and homosexual activities: Iran,[260] Saudi Arabia,[261] and in other Muslim-majority countries such as Egypt, Iraq, and the Indonesian province of Aceh,[262] same-sex sexual acts are illegal,[263] and LGBT people regularly face violence and discrimination.[264]

Women[edit]

Domestic violence[edit]

Many claim sharia law encourages domestic violence against women, when a husband suspects nushuz (disobedience, disloyalty, rebellion, ill conduct) in his wife.[265] Other scholars claim wife beating, for nashizah, is not consistent with modern perspectives of the Quran.[266]

One of the verses of the Quran relating to permissibility of domestic violence is Surah 4:34.[267][268] Sharia has been criticized for ignoring women's rights in domestic abuse cases.[269][270][271][272] Musawah, CEDAW, KAFA and other organizations have proposed ways to modify sharia-inspired laws to improve women's rights in Islamic nations, including women's rights in domestic abuse cases.[273][274][275][276]

Personal status laws and child marriage[edit]

Shari'a is the basis for personal status laws in most Islamic majority nations. These personal status laws determine rights of women in matters of marriage, divorce and child custody. A 2011 UNICEF report concludes that sharia law provisions are discriminatory against women from a human rights perspective. In legal proceedings under sharia law, a woman’s testimony is worth half of a man’s before a court.[162]

Except for Iran[citation needed], Lebanon[citation needed] and Bahrain[citation needed] which allow child marriages[citation needed], the civil code in Islamic majority countries do not allow child marriage of girls. However, with sharia personal status laws, sharia courts in all these nations have the power to override the civil code. The religious courts permit girls less than 18 years old to marry. As of 2011, child marriages are common in a few Middle Eastern countries, accounting for 1 in 6 all marriages in Egypt and 1 in 3 marriages in Yemen. UNICEF and other studies state that the top five nations in the world with highest observed child marriage rates – Niger (75%), Chad (72%), Mali (71%), Bangladesh (64%), Guinea (63%) – are Islamic-majority countries where the personal laws for Muslims are sharia-based.[277][278]

Rape is considered a crime in all countries, but sharia courts in Bahrain, Iraq, Jordan, Libya, Morocco, Syria and Tunisia in some cases allow a rapist to escape punishment by marrying his victim, while in other cases the victim who complains is often prosecuted with the crime of Zina (adultery).[162][279][280]

Women's right to property and consent[edit]

Sharia grants women the right to inherit property from other family members, and these rights are detailed in the Quran.[281] A woman's inheritance is unequal and less than a man's, and dependent on many factors.[Quran 4:12][282] For instance, a daughter's inheritance is usually half that of her brother's.[Quran 4:11][282]

Until the 20th century, Islamic law granted Muslim women certain legal rights, such as the right to own property received as Mahr (brideprice) at her marriage.[283][284] However, Islamic law does not grant non-Muslim women the same legal rights as the few it did grant Muslim women. Sharia recognizes the basic inequality between master and women slave, between free women and slave women, between Believers and non-Believers, as well as their unequal rights.[285][286] Sharia authorized the institution of slavery, using the words abd (slave) and the phrase ma malakat aymanukum ("that which your right hand owns") to refer to women slaves, seized as captives of war.[285][287] Under Islamic law, Muslim men could have sexual relations with female captives and slaves.[288][289]

Slave women under sharia did not have a right to own property or to move freely.[290][291] Sharia, in Islam's history, provided a religious foundation for enslaving non-Muslim women (and men), but nevertheless encouraged the manumission of slaves. However, manumission required that the non-Muslim slave first convert to Islam.[292][293] A non-Muslim slave woman who bore children to her Muslim master became legally free upon her master's death, and her children were presumed to be Muslims like their father, in Africa[292] and elsewhere.[294]

Starting with the 20th century, Western legal systems evolved to expand women's rights, but women's rights under Islamic law have remained tied to the Quran, hadiths and their fundamentalist interpretation as sharia by Islamic jurists.[289][295]

Parallels with Western legal systems[edit]

Elements of Islamic law have parallels in western legal systems. As example, the influence of Islam on the development of an international law of the sea can be discerned alongside that of the Roman influence.[296]

Makdisi states Islamic law also parallels the legal scholastic system in the West, which gave rise to the modern university system.[297] He writes that the triple status of faqih ("master of law"), mufti ("professor of legal opinions") and mudarris ("teacher"), conferred by the classical Islamic legal degree, had its equivalents in the medieval Latin terms magister, professor and doctor, respectively, although they all came to be used synonymously in both East and West.[297] Makdisi suggests that the medieval European doctorate, licentia docendi was modeled on the Islamic degree ijazat al-tadris wa-l-ifta’, of which it is a word-for-word translation, with the term ifta’ (issuing of fatwas) omitted.[297][298] He also argues that these systems shared fundamental freedoms: the freedom of a professor to profess his personal opinion and the freedom of a student to pass judgement on what he is learning.[297]

There are differences between Islamic and Western legal systems. For example, sharia classically recognizes only natural persons, and never developed the concept of a legal person, or corporation, i.e., a legal entity that limits the liabilities of its managers, shareholders, and employees; exists beyond the lifetimes of its founders; and that can own assets, sign contracts, and appear in court through representatives.[299] Interest prohibitions imposed secondary costs by discouraging record keeping and delaying the introduction of modern accounting.[300] Such factors, according to Timur Kuran, have played a significant role in retarding economic development in the Middle East.[301]

See also[edit]

|

|

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ While the advocacy of hudud punishments has gained symbolic importance, and in theory often involved rejection of the stringent traditional restrictions on their application, in practice, in those few countries where they have been reintroduced, they have often been used sparingly or not at all. Their application has varied depending on local political climate.[3][7]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b "British & World English: sharia". Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- ^ a b c d e John L. Esposito, ed. (2014). "Islamic Law". The Oxford Dictionary of Islam. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Knut S. Vikør (2014). "Sharīʿah". In Emad El-Din Shahin. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Islam and Politics. Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b c d e f g Norman Calder, Joseph A. Kéchichian, Farhat J. Ziadeh, Abdulaziz Sachedina, Jocelyn Hendrickson, Ann Elizabeth Mayer, Intisar A. Rabb (2009). "Law". In John L. Esposito. The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ John L. Esposito, Natana J. DeLong-Bas (2001), Women in Muslim family law, p. 2. Syracuse University Press, ISBN 978-0815629085. Quote: "[...], by the ninth century, the classical theory of law fixed the sources of Islamic law at four: the Quran, the Sunnah of the Prophet, qiyas (analogical reasoning), and ijma (consensus)."

- ^ Otto 2008, p. 19.

- ^ Otto 2008, p. 20.

- ^ Staff (January 3, 2003). "Analysis: Nigeria's Sharia Split". BBC News. Retrieved September 19, 2011. "Thousands of people have been killed in fighting between Christians and Muslims following the introduction of sharia punishments in northern Nigerian states over the past three years".

- ^ Harnischfeger, Johannes (2008).

• p. 16. "When the Governor of Kaduna announced the introduction of Sharia, although non-Muslims form almost half of the population, violence erupted, leaving more than 1,000 people dead."

• p. 189. "When a violent confrontation loomed in February 200, because the strong Christian minority in Kaduna was unwilling to accept the proposed sharia law, the sultan and his delegation of 18 emirs went to see the governor and insisted on the passage of the bill." - ^ "Features – A Guide to the Israeli Legal System". LLRX.com. 2001-01-15. Retrieved 2016-03-22.

- ^ Otto 2008, pp. 18–20.

- ^ Stahnke, Tad and Robert C. Blitt (2005), "The Religion-State Relationship and the Right to Freedom of Religion or Belief: A Comparative Textual Analysis of the Constitutions of Predominantly Muslim Countries." Georgetown Journal of International Law, volume 36, issue 4; also see Sharia Law profile by Country, Emory University (2011)

- ^ a b c d e f An-Na'im, Abdullahi A (1996). "Islamic Foundations of Religious Human Rights". In Witte, John; van der Vyver, Johan D. Religious Human Rights in Global Perspective: Religious Perspectives. pp. 337–59. ISBN 978-90-411-0179-2.

- ^ Hajjar, Lisa (2004). "Religion, State Power, and Domestic Violence in Muslim Societies: A Framework for Comparative Analysis". Law & Social Inquiry. 29 (1): 1–38. doi:10.1111/j.1747-4469.2004.tb00329.x. JSTOR 4092696.

- ^ Al-Suwaidi, J. (1995). Arab and western conceptions of democracy; in Democracy, war, and peace in the Middle East (Editors: David Garnham, Mark A. Tessler), Indiana University Press, see Chapters 5 and 6; ISBN 978-0253209399[page needed]

- ^ a b c d e f g Calder & Hooker 2007, p. 321.

- ^ a b c d e Calder & Hooker 2007, p. 326.

- ^ Abdal-Haqq, Irshad (2006). Understanding Islamic Law – From Classical to Contemporary (edited by Aminah Beverly McCloud). Chapter 1 Islamic Law – An Overview of its Origin and Elements. AltaMira Press. p. 4.

- ^ Hashim Kamali, Mohammad (2008). Shari'ah Law: An Introduction. Oneworld Publications. pp. 2, 14. ISBN 978-1851685653.

- ^ a b Weiss, Bernard G. (1998). The Spirit of Islamic Law. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-8203-1977-3.

- ^ Ullmann, M. (2002), Wörterbuch der griechisch-arabischen Übersetzungen des neunten Jahrhunderts, Wiesbaden, p. 437. Rom. 7: 22: ‘συνήδομαι γὰρ τῷ νόμῳ τοῦ θεοῦ’ is translated as ‘أني أفرح بشريعة الله’

- ^ Calder & Hooker 2007, p. 322.

- ^ Calder & Hooker 2007, p. 323.

- ^ Hodgson, Marshall (1958). The Venture of Islam Conscience and History in a World Civilization Vol 1. University of Chicago. pp. 155–56.

- ^ Weiss (2002), pp. 3, 161.

- ^ a b Dien, Mawil Izzi. Islamic Law: From Historical Foundations To Contemporary Practice. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2004.[page needed]

- ^ Khadduri & Liebesny 1955, p. 37.

- ^ Khadduri & Liebesny 1955, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Khadduri & Liebesny 1955, p. 58.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ramadan 2006, pp. 6–21.

- ^ Weiss (2002). p. 162.

- ^ a b Baber Johansen (1998), Contingency in a Sacred Law: Legal and Ethical Norms in the Muslim Fiqh, Brill Academic, ISBN 978-9004106031, pp. 23–32

- ^ Hallaq, Wael B. (November 1993). "Was al-Shafii the Master Architect of Islamic Jurisprudence?". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 25 (4): 587–605. doi:10.1017/s0020743800059274. JSTOR 164536.

- ^ Badr, Gamal M.; Mayer, Ann Elizabeth (1984). "Islamic Criminal Justice". The American Journal of Comparative Law. 32 (1): 167–69. doi:10.2307/840274. JSTOR 840274.

- ^ El-Gamal 2006, p. 16.

- ^ Makdisi 1999, p. [page needed].

- ^ Makdisi 2005, p. [page needed].

- ^ Khadduri & Liebesny 1955, pp. 60–61.

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20060522000137/http://www.averroes-foundation.org/articles/sex_slavery.html. Archived from the original on May 22, 2006. Retrieved February 14, 2006. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20060708103623/http://www.averroes-foundation.org/articles/islamic_law_evolving.html. Archived from the original on July 8, 2006. Retrieved February 12, 2006. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20060708103932/http://www.averroes-foundation.org/articles/free_and_equal.html. Archived from the original on July 8, 2006. Retrieved February 14, 2006. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ^ a b Brown 1996[page needed]

- ^ Hallaq 2001[page needed]

- ^ Ramadan 2005[page needed]

- ^ a b Aslan 2006[page needed]

- ^ Safi 2003[page needed]

- ^ Nenezich 2006[page needed]

- ^ Lapidus, Ira (edited by Francis Robinson) (1996). The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Islamic World. Cambridge University Press. p. 292. see Bibliography for Conclusion.

- ^ Hamoud, Hassan R. "Illiteracy in the Arab World". Background paper prepared for the Education for All Global Monitoring Report 2006, Literacy for Life UNESCO.

- ^ Esposito (2004), "Shariah", pg. 288

- ^ Calder & Hooker 2007, p. [page needed]: "Within Muslim discourse, sharia designates the rules and regulations governing the lives of Muslims, derived in principle from the Kuran and hadith. In this sense, the word is closely associated with fiḳh [q.v.], which signifies academic discussion of divine law."

- ^ a b Gibb, Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen (1970). Mohammedanism – An Historical Survey. Oxford University Press. p. 68. ISBN 0-19-500245-8.

- ^ a b Hunt Janin and Andre Kahlmeyer in Islamic Law: the Sharia from Muhammad's Time to the Present by Hunt Janin and Andre Kahlmeyer, McFarland and Co. Publishers, 2007, p. 3. ISBN 0786429216

- ^ The Sharia and The Nation State: Who Can Codify the Divine Law? p. 2. Accessed 20 September 2005.

- ^ Basim Musallam, The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Islamic World edited by Francis Robinson. Cambridge University Press, 1996, p. 176.

- ^ Marshall Hodgson, The Venture of Islam Conscience and History in a World Civilization Vol 3. University of Chicago, 1958, pp. 105–08.

- ^ Marshall Hodgson, The Venture of Islam Conscience and History in a World Civilization Vol 3. University of Chicago, 1958, pp. 176–77.

- ^ Sarah Ansari, The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Islamic World edited by Francis Robinson. Cambridge University Press, 1996, p. 90.

- ^ Marshall Hodgson, The Venture of Islam Conscience and History in a World Civilization Vol 3. University of Chicago, 1958, pp. 366–67.

- ^ Ansari, Sarah. The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Islamic World edited by Francis Robinson. Cambridge University Press, 1996, pp. 103–11.

- ^ Hodgson, Marshall. The Venture of Islam Conscience and History in a World Civilization Vol 3. University of Chicago, 1958, pp. 384–86.

- ^ Otto 2008, p. 30.

- ^ Fazlur Rahman (2009), The major themes of Quran, 2nd Edition, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0226702865

- ^ Shabbir Akhtar (2008), The Quran and the Secular Mind: A Philosophy of Islam, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415437837

- ^ Ramadan 2006, p. 4.

- ^ Ramadan 2006, pp. 12–3.

- ^ Glenn, H. Patrick (2014). p. 199.

- ^ a b Aisha Y. Musa, The Qur’anists, Florida International University, accessed May 22, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Neal Robinson (2013), Islam: A Concise Introduction, Routledge, ISBN 978-0878402243, Chapter 7, pp. 85–89

- ^ Edip Yuksel, Layth Saleh al-Shaiban, Martha Schulte-Nafeh, Quran: A Reformist Translation, Brainbow Press, 2007[page needed]

- ^ Al-Shibli, Sirat al-Numan, Lahore, n. d. Trans. Muhammad Tayyab Bakhsh Badauni as Method of Sifting Prophetic Tradition, Karachi, 1966. 179

- ^ Iqbal, Muhammad, The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam, edited by M. Saeed Sheikh, Adam Publishers and Distributors, Delhi, 1997 (also published earlier (in 1934) by the Oxford University Press), p. 137

- ^ a b Aisha Y. Musa, The Qur’anists, Florida International University, accessed May 22, 2013; Quote: "Stories relating the words and deeds of the Prophet Muhammad, known as Hadith in Arabic, have long been esteemed by the vast majority of Muslims as a source of law and guidance second only to the Qur’an in authority."

- ^ Quran 3:32, Quran 3:132, Quran 4:59, Quran 8:20, Quran 33:66

- ^ a b c Muhammad Qasim Zaman (2012), Modern Islamic Thought in a Radical Age, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1107096455, pp. 30–31

- ^ Jonathan A.C. Brown (2009), Hadith: Muhammad's Legacy in the Medieval and Modern World, Oneworld Publications, ISBN 978-1851686636, Chapter 2[page needed]

- ^ a b Moojan Momen (1987), An Introduction to Shiʻi Islam: The History and Doctrines of Twelver Shiʻism, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0300035315, pp. 173–75

- ^ a b William C. Chittick (1981), A Shi'ite Anthology, SUNY Press, ISBN 978-0873955102, pp. 5–12

- ^ Joseph Lowry (2010), in The Cambridge Companion to Muhammad (Editor: Jonathan E. Brockopp), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521713726, pp. 92–94

- ^ Hakeem, Farrukh B.; Haberfeld, M. R.; Verma, Arvind (2012). "Human Rights and Islamic Law". Policing Muslim Communities: Comparative International Context. Springer. pp. 41–57. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-3552-5_4. ISBN 978-1-4614-3552-5.

- ^ Jonathan A.C. Brown (2009), Hadith: Muhammad's Legacy in the Medieval and Modern World, Oneworld Publications, ISBN 978-1851686636, Chapter 4[page needed]

- ^ Cambridge Companion to the Quran. p. 60.

- ^ Whelan, Estelle (1998). "Forgotten Witness: Evidence for the Early Codification of the Qurʾān". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 118 (1): 1–14. doi:10.2307/606294. JSTOR 606294.

- ^ Hagarism: The Making of the Islamic World. pp. 18, 167.

- ^ Cambridge Companion to the Quran. p. 63.

- ^ Cambridge Companion to the Quran. pp. 62–63.

- ^ Cambridge Companion to the Quran. p. 62.

- ^ "British university reveals Quran parchment among oldest". DAWN. Dawn News. 22 July 2015. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ^ a b Motzki, Harald (2006). McAuliffe, Jane Dammen, ed. The Cambridge Companion to the Qur'ān. Cambridge University Press. pp. 59–67. ISBN 978-0-521-53934-0.[not specific enough to verify]

- ^ Rippin, A. (2009). "Al-Zuhrī, Naskh al-Qur'ān and the problem of early Tafsīr texts". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 47 (1): 22–43. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00022126. JSTOR 618316.

- ^ a b c Hallaq, Wael B. (2009). Sharī'a: Theory, Practice, Transformations. Cambridge University Press. pp. 96–97. ISBN 978-0-521-86147-2.

- ^ Haddad, Yvonne Yazbeck; Esposito, John L. (1997). Islam, Gender, & Social Change. Oxford University Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-19-511357-0.

- ^ Fatoohi, Louay (2012). Abrogation in the Qurʼan and Islamic Law. Routledge. pp. 3–6. ISBN 978-0-415-63198-3.

- ^ a b Ramadan 2006, pp. 5–7.

- ^ Ramadan 2006, p. 17.

- ^ Javaid Rehman et al (Editors), Religion, Human Rights and International Law, Brill Academic, ISBN 978-9004158269, p. 82 (notes 2-6)

- ^ Ramadan 2006, p. 18.

- ^ Ian Netton (2007), Encyclopaedia of Islam, ISBN 978-0700715886, pp. 230, 358–59

- ^ Ramadan 2006, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Chiragh Ali (2002), Modernist Islam 1840–1940: A Sourcebook, Edited by Charles Kurzman, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195154689, pp. 281–82

- ^ A.C. Brown, Jonathan (2014). Misquoting Muhammad: The Challenge and Choices of Interpreting the Prophet's Legacy. Oneworld Publications. p. 193. ISBN 978-1780744209.

Although it eventually became extinct, Tabari's madhhab flourished among Sunni ulama for two centuries after his death.

- ^ John Esposito, The History of Islam, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195107999[page needed]

- ^ Hallaq 1997[page needed]

- ^ Mohamed Keshavjee, Islam, Sharia and Alternative Dispute Resolution, Taurus, ISBN 978-1848857322[page needed]

- ^ Abdulaziz Abdulhussein Sachedina, The Just Ruler in Shi'ite Islam, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195119152[page needed]

- ^ Ramadan 2006, pp. 24–30.

- ^ Esposito, John L. (2010). The Future of Islam. Oxford University Press. pp. 74–77.

- ^ Esposito 1999, pp. 112–14.

- ^ Nazeer Ahmed (2001), Islam in Global History, (Xlibris) ISBN 978-0738859620.[page needed]

- ^ a b c Jurisprudence and Law – Islam Reorienting the Veil, University of North Carolina (2009)[page needed]

- ^ MN Pearson (2000), The Indian Ocean and the Red Sea, in The History of Islam in Africa (Ed: Nehemia Levtzion, Randall Pouwels), Ohio University Press, ISBN 978-0821412978, Chapter 2[page needed]

- ^ a b c d e Horrie & Chippindale 1991, p. 46.

- ^ Heck, Paul L. (2006), "Taxation", In Encyclopaedia of the Qur'an, vol. 5, (McAuliffe, Jane Dammen editor), Leiden: Brill Publishers. ISBN 90-04-14743-8

- ^ Medani Ahmed and Sebastian Gianci, Zakat, Encyclopedia of Taxation and Tax Policy (Cordes et al. editors), ISBN 978-0877666820, pp. 479–81

- ^ a b Horrie & Chippindale 1991, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Doi ARI. Shariah: The Islamic Law, AS Noordeen Publishers, Kuala Lumpur, ISBN 9679963330[full citation needed]

- ^ "Online Book". Abdurrahmandoi.net. Retrieved 2012-11-26.[self-published source?]

- ^ Shah, Niaz A (2011-03-03). Islamic Law and the Law of Armed Conflict: The Conflict in Pakistan. Taylor & Francis. p. 16. ISBN 9781136824685. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ^ Chapra, Muhammad Umer (2000), The Future of Economics: An Islamic Perspective, Leicester: The Islamic Foundation, p.118, ISBN 978-0-86037-2752

- ^ MOHAMAD YAZID, I; ASMADI, M.N; MOHD LIKI, H (March 2015). "The Practices of Islamic Finance in Upholding the Islamic" (PDF). International Review of Management and Business Research. 4 (1): 286–87. Retrieved 27 August 2015.