Epicurus

| Epicurus | |

|---|---|

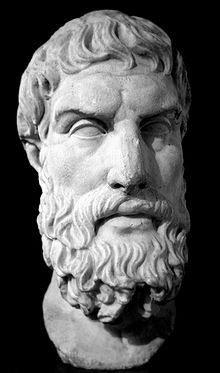

Roman marble bust of Epicurus

|

|

| Born | February 341 BC Samos |

| Died | 270 BC Athens |

| Ethnicity | Greek |

| Era | Ancient philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Epicureanism |

|

Main interests

|

Atomism, materialism |

|

Notable ideas

|

'Moving' pleasures (κατὰ κίνησιν ἡδοναί) and 'static' pleasures (καταστηματικαὶ ἡδοναί)[1] |

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

Epicurus (/ˌɛpɪˈkjʊərəs/ or /ˌɛpɪˈkjɔːrəs/;[2] Greek: Ἐπίκουρος, Epíkouros, "ally, comrade"; 341–270 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher as well as the founder of the school of philosophy called Epicureanism. Only a few fragments and letters of Epicurus's 300 written works remain. Much of what is known about Epicurean philosophy derives from later followers and commentators.

For Epicurus, the purpose of philosophy was to attain the happy, tranquil life, characterized by ataraxia—peace and freedom from fear—and aponia—the absence of pain—and by living a self-sufficient life surrounded by friends. He taught that pleasure and pain are measures of what is good and evil; death is the end of both body and soul and should therefore not be feared; the gods neither reward nor punish humans; the universe is infinite and eternal; and events in the world are ultimately based on the motions and interactions of atoms moving in empty space.

Contents

Biography[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Hedonism |

|---|

|

Schools of hedonism

|

|

Key concepts

|

|

Related articles

|

His parents, Neocles and Chaerestrate, both Athenian-born, and his father a citizen, had emigrated to the Athenian settlement on the Aegean island of Samos about ten years before Epicurus's birth in February 341 BC.[3] As a boy, he studied philosophy for four years under the Platonist teacher Pamphilus. At the age of eighteen, he went to Athens for his two-year term of military service. The playwright Menander served in the same age-class of the ephebes as Epicurus.

After the death of Alexander the Great, Perdiccas expelled the Athenian settlers on Samos to Colophon, on the coast of what is now Turkey. After the completion of his military service, Epicurus joined his family there. He studied under Nausiphanes, who followed the teachings of Democritus. In 311/310 BC Epicurus taught in Mytilene but caused strife and was forced to leave. He then founded a school in Lampsacus before returning to Athens in 306 BC where he remained until his death.[4] There he founded The Garden (κῆπος), a school named for the garden he owned that served as the school's meeting place, about halfway between the locations of two other schools of philosophy, the Stoa and the Academy.

Even though many of his teachings were heavily influenced by earlier thinkers, especially by Democritus, he differed in a significant way with Democritus on determinism. Epicurus would often deny this influence, denounce other philosophers as confused, and claim to be "self-taught".[5]

Epicurus never married and had no known children. He was most likely a vegetarian.[6][7] He suffered from kidney stones,[8] to which he finally succumbed in 270 BC[9] at the age of seventy-two, and despite the prolonged pain involved, he wrote to Idomeneus:

I have written this letter to you on a happy day to me, which is also the last day of my life. For I have been attacked by a painful inability to urinate, and also dysentery, so violent that nothing can be added to the violence of my sufferings. But the cheerfulness of my mind, which comes from the recollection of all my philosophical contemplation, counterbalances all these afflictions. And I beg you to take care of the children of Metrodorus, in a manner worthy of the devotion shown by the young man to me, and to philosophy.[10]

The school[edit]

Epicurus' school, which was based in the garden of his house and thus called "The Garden",[11] had a small but devoted following in his lifetime. The primary members were Hermarchus, the financier Idomeneus, Leonteus and his wife Themista, the satirist Colotes, the mathematician Polyaenus of Lampsacus, Leontion, and Metrodorus of Lampsacus, the most famous popularizer of Epicureanism. His school was the first of the ancient Greek philosophical schools to admit women as a rule rather than an exception.[12] An inscription on the gate to The Garden is recorded by Seneca in epistle XXI of Epistulae morales ad Lucilium:[13]

Stranger, here you will do well to tarry; here our highest good is pleasure.

Epicurus emphasized friendship as an important ingredient of happiness, and the school resembled in many ways a community of friends living together. However, he also instituted a hierarchical system of levels among his followers, and had them swear an oath on his core tenets.

Teachings[edit]

Prefiguring science and ethics[edit]

Epicurus is a key figure in the development of science and scientific methodology because of his insistence that nothing should be believed, except that which was tested through direct observation and logical deduction. He was a key figure in the Axial Age, the period from 800 BC to 200 BC, during which, according to Karl Jaspers, similar thinking appeared in China, India, Iran, the Near East, and Ancient Greece. His statement of the Ethic of Reciprocity as the foundation of ethics is the earliest in Ancient Greece, and he differs from the formulation of utilitarianism by Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill by emphasizing the minimization of harm to oneself and others as the way to maximize happiness.

Epicurus's teachings represented a departure from the other major Greek thinkers of his period, and before, but was nevertheless founded on many of the same principles as Democritus. Like Democritus, he was an atomist, believing that the fundamental constituents of the world were indivisible little bits of matter (atoms; Greek: ἄτομος atomos, "indivisible") flying through empty space (Greek: κενόν kenon). Everything that occurs is the result of the atoms colliding, rebounding, and becoming entangled with one another. His theory differs from the earlier atomism of Democritus because he admits that atoms do not always follow straight lines but their direction of motion may occasionally exhibit a "swerve" (Greek: παρέγκλισις parenklisis; Latin: clinamen). This allowed him to avoid the determinism implicit in the earlier atomism and to affirm free will.[14]

He regularly admitted women and slaves into his school and was one of the first Greeks to break from the god-fearing and god-worshiping tradition common at the time, even while affirming that religious activities are useful as a way to contemplate the gods and to use them as an example of the pleasant life. Epicurus participated in the activities of traditional Greek religion, but taught that one should avoid holding false opinions about the gods. The gods are immortal and blessed and men who ascribe any additional qualities that are alien to immortality and blessedness are, according to Epicurus, impious. The gods do not punish the bad and reward the good as the common man believes. The opinion of the crowd is, Epicurus claims, that the gods "send great evils to the wicked and great blessings to the righteous who model themselves after the gods," whereas Epicurus believes the gods, in reality, do not concern themselves at all with human beings.

It is not the man who denies the gods worshipped by the multitude, who is impious, but he who affirms of the gods what the multitude believes about them.[15]

Pleasure as absence of suffering[edit]

Epicurus' philosophy is based on the theory that all good and bad derive from the sensations of what he defined as pleasure and pain: What is good is what is pleasurable, and what is bad is what is painful. His ideas of pleasure and pain were ultimately, for Epicurus, the basis for the moral distinction between good and evil. If pain is chosen over pleasure in some cases it is only because it leads to a greater pleasure. Although Epicurus has been commonly misunderstood to advocate the rampant pursuit of pleasure, his teachings were more about striving for an absence of pain and suffering, both physical and mental, and a state of satiation and tranquility that was free of the fear of death and the retribution of the gods. Epicurus argued that when we do not suffer pain, we are no longer in need of pleasure, and we enter a state of ataraxia, "tranquility of soul" or "imperturbability".[16][17]

Epicurus' teachings were introduced into medical philosophy and practice by the Epicurean doctor Asclepiades of Bithynia, who was the first physician who introduced Greek medicine in Rome. Asclepiades introduced the friendly, sympathetic, pleasing and painless treatment of patients. He advocated humane treatment of mental disorders, had insane persons freed from confinement and treated them with natural therapy, such as diet and massages. His teachings are surprisingly modern, therefore Asclepiades is considered to be a pioneer physician in psychotherapy, physical therapy and molecular medicine.[18]

Epicurus explicitly warned against overindulgence because it often leads to pain. For instance, Epicurus warned against pursuing love too ardently. He defended friendships as ramparts for pleasure and denied them any inherent worth.[19] He also believed, contrary to Aristotle,[20] that death was not to be feared. When a man dies, he does not feel the pain of death because he no longer is and therefore feels nothing. Therefore, as Epicurus famously said, "death is nothing to us." When we exist, death is not; and when death exists, we are not. All sensation and consciousness ends with death and therefore in death there is neither pleasure nor pain. The fear of death arises from the belief that in death, there is awareness.

From this doctrine arose the Epicurean epitaph: Non fui, fui, non sum, non curo ("I was not; I was; I am not; I do not care"), which is inscribed on the gravestones of his followers and seen on many ancient gravestones of the Roman Empire. This quotation is often used today at humanist funerals.[21]

As an ethical guideline, Epicurus emphasized minimizing harm and maximizing happiness of oneself and others:

It is impossible to live a pleasant life without living wisely and well and justly, and it is impossible to live wisely and well and justly without living pleasantly.

- ("justly" meaning to prevent a "person from harming or being harmed by another")[22]

Epicurean paradox[edit]

The "Epicurean paradox" is a version of the problem of evil. Lactantius attributes this trilemma to Epicurus in De Ira Dei:

God, he says, either wishes to take away evils, and is unable; or He is able, and is unwilling; or He is neither willing nor able, or He is both willing and able. If He is willing and is unable, He is feeble, which is not in accordance with the character of God; if He is able and unwilling, He is envious, which is equally at variance with God; if He is neither willing nor able, He is both envious and feeble, and therefore not God; if He is both willing and able, which alone is suitable to God, from what source then are evils? Or why does He not remove them?

In Dialogues concerning Natural Religion (1779), David Hume also attributes the argument to Epicurus:

Epicurus’s old questions are yet unanswered. Is he willing to prevent evil, but not able? then is he impotent. Is he able, but not willing? then is he malevolent. Is he both able and willing? whence then is evil?

No extant writings of Epicurus contain this argument and it is possible that it has been misattributed to him.

Perhaps the earliest expression of the trilemma appears in the writings of the sceptic Sextus Empiricus (160–210 AD), who wrote in his Outlines of Pyrrhonism:

Further, this too should be said. Anyone who asserts that god exists either says that god takes care of the things in the cosmos or that he does not, and, if he does take care, that it is either of all things or of some. Now if he takes care of everything, there would be no particular evil thing and no evil in general in the cosmos; but the Dogmatists say that everything is full of evil; therefore god shall not be said to take care of everything. On the other hand, if he takes care of only some things, why does he take care of these and not of those? For either he wishes but is not able, or he is able but does not wish, or he neither wishes nor is able. If he both wished and was able, he would have taken care of everything; but, for the reasons stated above, he does not take care of everything; therefore, it is not the case that he both wishes and is able to take care of everything. But if he wishes and is not able, he is weaker than the cause on account of which he is not able to take care of the things of which he does not take care; but it is contrary to the concept of god that he should be weaker than anything. Again, if he is able to take care of everything but does not wish to do so, he will be considered malevolent, and if he neither wishes nor is able, he is both malevolent and weak; but to say that about god is impious. Therefore, god does not take care of the things in the cosmos.

Epistemology[edit]

Epicurus emphasized the senses in his epistemology, and his Principle of Multiple Explanations ("if several theories are consistent with the observed data, retain them all") is an early contribution to the philosophy of science.

There are also some things for which it is not enough to state a single cause, but several, of which one, however, is the case. Just as if you were to see the lifeless corpse of a man lying far away, it would be fitting to list all the causes of death in order to make sure that the single cause of this death may be stated. For you would not be able to establish conclusively that he died by the sword or of cold or of illness or perhaps by poison, but we know that there is something of this kind that happened to him.[23][24]

Politics[edit]

In contrast to the Stoics, Epicureans showed little interest in participating in the politics of the day, since doing so leads to trouble. He instead advocated seclusion. This principle is epitomized by the phrase lathe biōsas (λάθε βιώσας), meaning "live in obscurity", "get through life without drawing attention to yourself", i.e., live without pursuing glory or wealth or power, but anonymously, enjoying little things like food, the company of friends, etc. Plutarch elaborated on this theme in his essay Is the Saying "Live in Obscurity" Right? (Εἰ καλῶς εἴρηται τὸ λάθε βιώσας, An recte dictum sit latenter esse vivendum) 1128c; cf. Flavius Philostratus, Vita Apollonii 8.28.12.

But the Epicureans did have an innovative theory of justice as a social contract. Justice, Epicurus said, is an agreement neither to harm nor be harmed, and we need to have such a contract in order to enjoy fully the benefits of living together in a well-ordered society. Laws and punishments are needed to keep misguided fools in line who would otherwise break the contract. But the wise person sees the usefulness of justice, and because of his limited desires, he has no need to engage in the conduct prohibited by the laws in any case. Laws that are useful for promoting happiness are just, but those that are not useful are not just. (Principal Doctrines 31-40)

Legacy[edit]

Elements of Epicurean philosophy have resonated and resurfaced in various diverse thinkers and movements throughout Western intellectual history.

The atomic poems (such as 'All Things are Governed by Atoms') and natural philosophy of Margaret Cavendish were influenced by Epicurus.

His emphasis on minimizing harm and maximizing happiness in his formulation of the Ethic of Reciprocity was later picked up by the democratic thinkers of the French Revolution, and others, like John Locke, who wrote that people had a right to "life, liberty, and property."[25] To Locke, one's own body was part of one's property, and thus one's right to property would theoretically guarantee safety for one's person, as well as one's possessions.

This triad, as well as the egalitarianism of Epicurus, was carried forward into the American freedom movement and Declaration of Independence, by the American founding father, Thomas Jefferson, as "all men are created equal" and endowed with certain "unalienable rights," such as "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness." Jefferson considered himself an Epicurean.[26]

In An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, David Hume uses Epicurus as a character for explaining the impossibility of our knowing God to be any greater or better than his creation proves him to be.

Karl Marx's doctoral thesis was on The Difference Between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature.

Epicurus was first to assert human freedom as coming from a fundamental indeterminism in the motion of atoms. This has led some philosophers to think that for Epicurus free will was caused directly by chance. In his On the Nature of Things (De rerum natura), Lucretius appears to suggest this in the best-known passage on Epicurus' position.[27] But in his Letter to Menoeceus, Epicurus follows Aristotle and clearly identifies three possible causes - "some things happen of necessity, others by chance, others through our own agency." Aristotle said some things "depend on us" (eph'hemin). Epicurus agreed, and said it is to these last things that praise and blame naturally attach. For Epicurus, the "swerve" (or clinamen) of the atoms simply defeated determinism to leave room for autonomous agency.[28]

Epicurus was also a significant source of inspiration and interest for both Arthur Schopenhauer, having particular influence on the famous pessimist's views on suffering and death, as well as one of Schopenhauer's successors: Friedrich Nietzsche. Nietzsche cites his affinities to Epicurus in a number of his works, including The Gay Science, Beyond Good and Evil, and his private letters to Peter Gast. Nietzsche was attracted to, among other things, Epicurus' ability to maintain a cheerful philosophical outlook in the face of painful physical ailments. Nietzsche also suffered from a number of sicknesses during his lifetime. However, he thought that Epicurus' conception of happiness as freedom from anxiety was too passive and negative.

Works[edit]

The only surviving complete works by Epicurus are three letters, which are to be found in book X of Diogenes Laërtius' Lives of Eminent Philosophers, and two groups of quotes: the Principal Doctrines (Κύριαι Δόξαι), reported as well in Diogenes' book X, and the Vatican Sayings, preserved in a manuscript from the Vatican Library.

Numerous fragments of his thirty-seven volume treatise On Nature have been found among the charred papyrus fragments at the Villa of the Papyri at Herculaneum. In addition, other Epicurean writings found at Herculaneum contain important quotations from his other works. Moreover, numerous fragments and testimonies are found throughout ancient Greek and Roman literature, a collection of which can be found in Usener's Epicurea.

According to Diogenes Laertius, the major works of Epicurus include:

- Thirty-seven treatises on Natural Philosophy

- On Atoms and the Void

- On Love

- Abridgment of the Arguments employed against the Natural Philosophers

- Against the Doctrines of the Megarians

- Problems

- Fundamental Propositions

- On Choice and Avoidance

- On the Chief Good

- On the Criterion (the Canon)

- Chaeridemus, a treatise on the Gods

- On Piety

- Hegesianax

- Four essays on Lives

- Essay on Just Dealing

- Neocles

- Essay addressed to Themista

- The Banquet

- Eurylochus

- Essay addressed to Metrodorus

- Essay on Seeing

- Essay on the Angle in an Atom

- Essay on Touch

- Essay on Fate

- Opinions on the Passions

- Treatise addressed to Timocrates

- Prognostics

- Exhortations

- On Images

- On Perceptions

- Aristobulus

- Essay on Music

- On Justice and the other Virtues

- On Gifts and Gratitude

- Polymedes

- Timocrates (three books)

- Metrodorus (five books)

- Antidorus (two books)

- Opinions about Diseases, addressed to Mithras

- Callistolas

- Essay on Kingly Power

- Anaximenes

- Letters

Hero cult[edit]

According to Diskin Clay, Epicurus himself established a custom of celebrating his birthday annually with common meals, befitting his stature as heros ktistes (or founding hero) of the Garden. He ordained in his will annual memorial feasts for himself on the same date (10th of Gamelion month).[29] Epicurean communities continued this tradition,[30] referring to Epicurus as their "savior" (soter) and celebrating him as hero. Lucretius apotheosized Epicurus as the main character of his epic poem De rerum natura. The hero cult of Epicurus may have operated as a Garden variety civic religion.[31] However, clear evidence of an Epicurean hero cult, as well as the cult itself, seems buried by the weight of posthumous philosophical interpretation.[32] Epicurus' cheerful demeanor, as he continued to work despite dying from a painful stone blockage of his urinary tract lasting a fortnight, according to his successor Hermarchus and reported by his biographer Diogenes Laërtius, further enhanced his status among his followers. [8]

In literature and popular media[edit]

Paul the Apostle encountered Epicurean and Stoic philosophers as he was ministering in Athens.[33]

Horace describes himself as Epicuri de grege porcum "a swine from Epicurus's herd" in his Epistles.[34]

In Canto X Circle 6 ("Where the heretics lie") of Dante's Inferno, Epicurus and his followers are criticized for supporting a materialistic ideal when they are mentioned to have been condemned to the Circle of Heresy.

Epicurus the Sage is a two-part comic book by William Messner-Loebs and Sam Kieth portraying Epicurus as "the only sane philosopher" by anachronistically bringing him together with many other well-known Greek philosophers. It was republished as graphic novel by the Wildstorm branch of DC Comics.

In indie-rock band The 1975's song, The Sound, lead singer Matthew Healy states 'There's so much skin to see / It's a simple Epicurean philosophy'.

Epicurus and the Epicurism[edit]

In Rabbinic literature the term Epikoros is used, without a specific reference to the Greek philosopher Epicurus, yet it seems apparent that the term was derived from his name.[35]

Epicurus's apparent hedonistic views (as Epicurus' ethics was hedonistic) and philosophical teachings, though opposed to the Hedonists of his time, countered Jewish scripture, the strictly monotheistic conception of God in Judaism and the Jewish belief in the afterlife and the world to come.

The Talmudic interpretation is that the Aramaic word is derived from the root-word פק"ר (PKR; lit. licentious), hence disrespect.

The Christian censorship of the Jewish Talmud in the aftermath of the Disputation of Barcelona and during the Spanish Inquisition and Roman Inquisition, let the term spread within the Jewish classical texts, since Roman Catholic Church censors replaced terms like Minim ("sectarians", coined on the Christians) with the term Epikorsim or Epicursim, meaning heretics.[citation needed]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, The Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, X:136.

- ^ Jones, Daniel (2006). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary. 17th edition. Cambridge UP.

- ^ Apollodorus of Athens (reported by Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, 10.14–15) gives his birth on the fourth day of the month February in the third year of the 109th Olympiad, in the archonship of Sosigenes

- ^ "Epicurus - Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy".

- ^ http://www.jstor.org/stable/4182030

- ^ "The Hidden History of Greco-Roman Vegetarianism".

- ^ Dombrowski, Daniel A. (1984). The Philosophy of Vegetarianism. ISBN 0870234315.

- ^ a b Bitsori, Maria; Galanakis, Emmanouil (2004). "Epicurus' death". World Journal of Urology. 22 (6): 466–469. doi:10.1007/s00345-004-0448-2. PMID 15372192.

- ^ In the second year of the 127th Olympiad, in the archonship of Pytharatus, according to Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, 10.15

- ^ Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, 10.22 (trans. C.D. Yonge).

- ^ Long, A. A. (1986). Hellenistic philosophy: Stoics, Epicureans, Sceptics. p. 15.

- ^ Two women, Axiothea and Lastheneia, were known to have been admitted by Plato. See Hadot, Pierre. Qu'est-ce que la philosophie antique?, page 99, Gillimard 1995. Pythagoras is also believed to have inducted one woman, Theano, into his order.

- ^ "Epistulae morales ad Lucilium".

- ^ The only fragment in Greek about this central notion is from the Oenoanda inscription (fr. 54 in Smith's edition). The best known reference is in Lucretius's On the nature of things, [1].

- ^ letter by Epicurus to Menoeceus; see Diogenes Laërtius de clarorum philosophorum vitis, dogmatibus et apophthegmatibus libri decem (X, 123)

- ^ Folse, Henry (2005). How Epicurean Metaphysics leads to Epicurean Ethics. Department of Philosophy, Loyola University, New Orleans, LA.

- ^ Konstan, David. Epicurus, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2013 Edition).forthcoming URL = <http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2013/entries/epicurus/>

- ^ C, Yapijakis (2009). "Hippocrates of Kos, the father of clinical medicine, and Asclepiades of Bithynia, the father of molecular medicine. Review". In Vivo. 23 (4): 507–14. PMID 19567383.

- ^ Cicero, Marcus Tullius. "II.82". De finibus bonorum et malorum. ISBN 3-519-01219-7.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Stephen. Appraising Death In Human Life: Two Modes Of Valuation, in French, Peter, and Wettstein, Howard (editors), Life And Death: Metaphysics And Ethics, Midwest Studies In Philosophy, volume XXIV. Blackwell Publishers, Inc., 2000, p.153 (Aristotle 'seems to have believed [in] fearing death ... . [But] his conclusion should be understood to be [merely] that the fact that a person dies is bad [because] nothing is any longer good or bad for him or her.') Books.Google.com (accessed 2011-Feb-04)

- ^ "Epicurus (c 341-270 BC)". British Humanist Association.

- ^ "Epicurus Principal Doctrines 5 and 31 transl. by Robert Drew Hicks". 1925.

- ^ Lucretius.[full citation needed]

- ^ The poem version can be found in: Carus, Titus Lucretius (Jul 2008). Of The Nature of Things. Project Gutenberg EBook. 785. William Ellery Leonard (translator). Project Gutenberg. Book VI, Section Extraordinary and Paradoxical Telluric Phenomena, Line 9549–9560

- ^ John Locke (1689) "Two Treatises of Government#Property"

- ^ Jefferson considered himself an Epicurean (1819): "Letter, Thomas Jefferson to William Short"

- ^ 2.251-262 "On the Nature of Things, 289-293" Check

|url=value (help). - ^ "Epicurus page on Information Philosopher; cf. Letter to Menoeceus, §134.".

- ^ D. Smith, Nicholas. Reason and religion in Socratic philosophy. p. 160. ISBN 0-19-513322-6.

- ^ Glad, Clarence E. Paul and Philodemus: adaptability in Epicurean and early Christian psychology. p. 176. ISBN 90-04-10067-9.

- ^ Nussbaum, Martha Craven. The Therapy of Desire: Theory and Practice in Hellenistic Ethics. p. 119. ISBN 0-691-14131-2.

- ^ Clay, Diskin. Paradosis and survival: three chapters in the history of Epicurean philosophy. p. 76. ISBN 0-472-10896-4.

- ^ The Holy Bible, Acts 17:18

- ^ Horace, Epistles Bk I, ep. 4 v. 16.

- ^ "Epikoros". encyclopedia.com.

References[edit]

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). "Epicurus". Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. 2:10. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). "Epicurus". Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. 2:10. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.

Further reading[edit]

- Texts

- Epicurus (1994). Inwood, Brad; Gerson, Lloyd P., eds. The Epicurus Reader. Selected Writings and Testimonia. Indianapolis: Hackett. ISBN 0-87220-242-9.

- Epicurus (1993). The essential Epicurus : letters, principal doctrines, Vatican sayings, and fragments. Eugene O'Connor, trans. Buffalo, N.Y.: Prometheus Books. ISBN 0-87975-810-4.

- Epicurus (1964). Letters, principal doctrines, and Vatican sayings. Russel M. Geer, trans. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill.

- Laertius, Diogenes (1969). Caponigri, A. Robert, ed. Lives of the Philosophers. Chicago: Henry Regnery Co.

- Lucretius Carus, Titus (1976). On the nature of the universe. R. E. Latham, trans. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-044018-6.

- Körte, Alfred (1987). Epicureanism : two collections of fragments and studies (in Greek). New York: Garland. ISBN 0-8240-6915-3.

- Oates, Whitney J. (1940). The Stoic and Epicurean philosophers, The Complete Extant Writings of Epicurus, Epictetus, Lucretius and Marcus Aurelius. New York: Modern Library.

- Diogenes of Oinoanda (1993). The Epicurean inscription. Martin Ferguson Smith, trans. Napoli: Bibliopolis. ISBN 88-7088-270-5.

- Studies

- Bailey C. (1928). The Greek Atomists and Epicurus, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Bakalis, Nikolaos (2005). Handbook of Greek Philosophy from Thales to the Stoics. Analysis and fragments. Victoria: Trafford. ISBN 1-4120-4843-5.

- Gordon, Pamela (1996). Epicurus in Lycia. The Second-Century World of Diogenes of Oenoanda. Ann Arbor: Univ. of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-10461-6.

- Gottlieb, Anthony (2000). The Dream of Reason. A History of Western Philosophy from the Greeks to the Renaissance. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-04951-5.

- Hibler, Richard W. (1984). Happiness Through Tranquillity. The school of Epicurus. Lanham, MD: University Press of America. ISBN 0-8191-3861-4.

- Hicks, R. D. (1910). Stoic and Epicurean. New York: Scribner.

- Jones, Howard (1989). The Epicurean Tradition. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-02069-7.

- O'Keefe, Tim (2009). Epicureanism. University of California Press.

- Panichas, George Andrew (1967). Epicurus. New York: Twayne Publishers.

- Rist, J.M. (1972). Epicurus. An introduction. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-08426-1.

- Warren, James (2009). The Cambridge Companion to Epicureanism. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-05218-7347-5.

- William Wallace. Epicureanism. SPCK (1880)

External links[edit]

Media related to Epicurus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Epicurus at Wikimedia Commons Quotations related to Epicurus at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Epicurus at Wikiquote Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: Κύριαι Δόξαι

Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: Κύριαι Δόξαι Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: Ἐπιστολὴ πρὸς Μενοικέα

Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: Ἐπιστολὴ πρὸς Μενοικέα- Society of Friends of Epicurus – Epicurean community

- Konstan, David. "Epicurus". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- O'Keefe, Tim. "Epicurus". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Stoic And Epicurean by Robert Drew Hicks (1910) (Internet Archive)

- Epicurus.net – Epicurus and Epicurean Philosophy

- Epicurus and Lucretius – small article by "P. Dionysius Mus"

- The Difference Between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature – Karl Marx's doctoral thesis

- Epicurus on Free Will

- The Garden of Epicurus – useful summary of the teachings of Epicurus

- Philosophy of Happiness (PDF)

- Epicurea, Hermann Usener - full text

- Works by or about Epicurus at Internet Archive

- Works by Epicurus at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Portrait

- Primary sources

- Principal Doctrines – unidentified translation

- Principal Doctrines – the original Greek, two English translations, and a parallel mode

- Vatican Sayings – unidentified translation

- Vatican Sayings – the original Greek with an English translation

- Letter to Herodotus

- Letter to Pythocles

- Letter to Menoeceus

- Epicurus: Fragments - Usener's compilation in English translation

- 341 BC births

- 270 BC deaths

- 4th-century BC Greek people

- 3rd-century BC Greek people

- 3rd-century BC philosophers

- 3rd-century BC writers

- Ancient Greek philosophers

- Ancient Samians

- Epicurean philosophers

- Greek historical hero cult

- Hellenistic-era philosophers

- Materialists

- Moral philosophers

- Philosophers of science

- Religious skeptics

- Critics of religions

- Ancient Greek agnostics