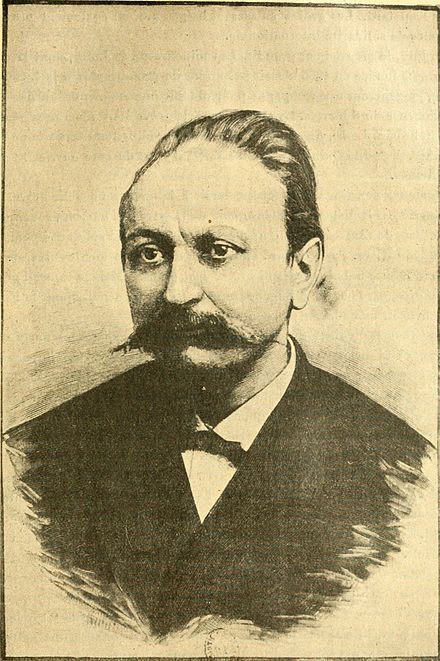

October 13th marks the 113th anniversary of the Spanish state’s execution of the libertarian revolutionary Francisco Ferrer (1859-1909), who tried to establish “Modern Schools” in Spain, for boys and girls, that were rationalist and anti-authoritarian. But he was also a revolutionary in the more political sense, supporting the efforts of radical working class movements to abolish the state and capitalism, and to create a free society based on workers’ self-management. This made him a target for state repression. When the workers in Barcelona arose in revolt in July 1909, in the face of mass conscription to fight in Spanish Morocco and mass lockouts by the employers, leading to a week of armed struggle, Ferrer was accused of being one of the instigators, when in reality he played virtually no role in the uprising. His crime was preaching and practicing “free thought” in a country where education was controlled by a reactionary Catholic Church, and providing funds and support to radicals and revolutionaries. The following excerpts are taken from Chapter 10 of his book, The Origins and Ideals of the Modern School (first published in 1908; English translation, 1913). Ferrer’s rejection of rewards and punishments as teaching “methods” was shared by other anarchists involved in libertarian education, from William Godwin, to Sebastien Faure, to people like Paul Goodman and Joel Spring. In Volume One of Anarchism: A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas, I included Ferrer’s essay, “L’École Rénovée,” which summarizes his libertarian approach to education.

No Reward or Punishment

Rational education is, above all things, a means of defence against error and ignorance. To ignore truth and accept absurdities is, unhappily, a common feature in our social order; to that we owe the distinction of classes and the persistent antagonism of interests. Having admitted and practised the co-education of boys and girls, of rich and poor — having that is to say started from the principle of solidarity and inequality — we are not prepared to create a new inequality. Hence in the Modern School there will be no rewards and no punishments; there will be no examinations to puff up some children withe the flattering title of excellent, to give others the vulgar title of “good”, and make others unhappy with a consciousness of incapacity and failure. These features of the existing official and religious schools, which are quite in accord with their reactionary environment and aim, cannot, for the reasons I have given, be admitted in to the Modern School. Since we are not educating for a specific purpose, we cannot determine the capacity or incapacity of the child. When we teach a sciend, or art, or trade, or some subject requiring special conditions, an examination may be useful, all(] there may be reason to give a diploma or refuse one; I neither affirm nor deny it. But there is no such specialism in the Modern School. characteristic note of the school, distinguishing It even from some which pass as progressive models, is that in it the faculties of the children shall develop freely without subjection to any dogmatic patron, not even to what it may consider the body of convictions of the founder and teachers; every pupil shall go forth from it Into social life with the ability to be his own master and guide his own life in all things.

Hence, if we were rationally prevented from giving prizes, we could not impose penalties, and no one Would have dreamed of doing so In our school if the idea had not been suggested from without. Sometimes parents came to me with the rank proverb, “Letters go in with blood,” on their lips, and begged me to punish their children. Others who were charmed with the precocious talent. of their children wanted to see them shine in examinations and exhibit medals. We refused to admit either prizes or punishments , and Sent the parents away. 11’ any child were conspicuous for merit, application, laziness, or bad conduct, we pointed out to it the need of accord, or the unhappiness of lack of accord, with its own welfare and that of others, and the teacher might give a lecture oil the subject. Nothing more was (]oil(,, and the parents were gradually reconciled to the system, though they often had to be corrected in their errors and prejudices by their own children.

Nevertheless, the old prejudice was constantly recurring, and I saw that I had to repeat my arguments with the parents of new pupils. I therefore wrote the following article in the Bulletin:

The conventional examinations which we usually find held at file end of a scholastic year, to which our fathers attached so much Importance, have had no result at all; or, if any result, a bad one. These functions and their accompanying solemnities seem to have been instituted for the sole purpose of satisfying the vanity of parents and the selfish interests of many teachers, and in order to put the children to torture before the examination and make them ill afterwards. Each father wants his child to be presented in public as one of the prodigies of the college, and regards him with pride as a learned man in miniature He does not notice that for a fortnight or so the child suffers exquisite torture. As things are judged by external appearances, It is not thought that there is ally real torture, as there is not the least scratch visible on the skin ……

The parent’s lack of acquaintance with the natural disposition of the child, and the iniquity of putting it in false conditions so that its intellectual powers, especially in the sphere of memory, are artificially stimulated, prevent the parent from seeing that this measure of personal gratification may, as has happened in many cases, lead to Illness and to the moral, if not the physical, death of the, child.

On the other hand, the majority of teachers, being mere stereotypers of ready — made phrases and mechanical innoculators, rather than moral fathers of their pupils, are concerned in these examinations with their own personality and their economic interests. Their object is to let the parents and the others who are present at the public display see that, under their guidance, the child has learned a good deal, that its knowledge is greater in quantity and quality than could have been expected of its tender years and in view of the short time that it has been under the charge of this very skilful teacher.

In addition to this wretched vanity, which is satisfied at the cost of the moral and physical life of the child, the teachers are anxious to elicit compliments from the parents and the rest of the audience, who know nothing of the real state of things, as a kind of advertisement of the prestige of their particular school.

Briefly, we are inexorably opposed to holding public examinations. In Our school everything must be done for the advantage of the pupil. Everything that does ]lot conduce to this end must be recognised as opposed to the natural spirit of positive education. Examinations do no good, and they do much harm to the child. Besides the Illness of which we have already spoken, the nervous system of the child suffers, and a kind of temporary paralysis is inflicted on its conscience by the immoral features of the examination; the vanity provoked In those who are placed highest, envy and humiliation grave obstacles to sound growth, in those who have failed, and in all of them the gel-ills of’ most of the sentiments which go to the making of egoism.

In a later number of the Bulletin I found it necessary to return to the subject:

We frequently receive letters from Workers’ Educational Societies and Republican Fraternities asking that the teachers shall chastise the children in our schools. We ourselves have been disgusted, during our brief excursions, to find material proofs of the fact which is at the base of this request; we have seen children on their knees, or in other attitudes of punishment.

These irrational and atavistic practices must disappear. Modern pædagogy entirely discredits them. The teachers who offer their services to the Modern School, or ask our recommendation to teach in similar schools, must refrain from any moral or material punishment, under penalty of being disqualified permanently. Scolding, impatience, and anger ought to disappear with the ancient title of “master.” In free schools all should be peace, gladness, and fraternity. We trust that this will suffice to put an end to these practices, which are most improper in people whose sole ideal is the training of a generation fitted to establish a really fraternal, harmonious, and just state of society.

Francisco Ferrer Guardia, 1908