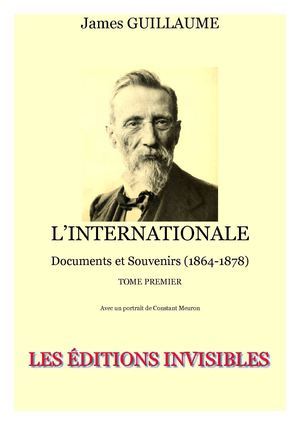

James Guillaume (1866)

James Guillaume (1844-1916) was one of the leading militants of the Swiss Jura Federation in the International Workingmen’s Association. I have discussed his role in the struggles within the International over the proper direction of working class and socialist movements in ‘We Do Not Fear Anarchy – We Invoke It’: The First International and the Origins of the Anarchist Movement. After he was expelled, along with Bakunin, from the Marxist faction of the International at the Hague Congress in 1872, Guillaume was instrumental in reconstituting the International along anti-authoritarian lines, playing an important role in producing the Sonvillier Circular in 1871, which denounced Marx’s attempts to centralize control of the International in the hands of the General Council in London, and to impose as official policy a commitment to the creation of national political parties whose object was to be the conquest of political power on behalf of the working class. After the Hague Congress, Guillaume and Bakunin, together with Internationalists from Spain, France, Italy and Switzerland, organized the St. Imier Congress, which resulted in a bold declaration of their revolutionary aims and a denunciation of Marxist policies and methods (both documents are in Volume One of Anarchism: A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas). Guillaume is very much the hero in René Berthier’s recent book, Social Democracy and Anarchism, which as I noted previously tries to show that the anarchist movements that emerged from the International somehow constituted a “break” with Bakunin’s “revolutionary socialism,” rather than a continuation of it. I disagree, and so would have the anarchist historian and Bakunin biographer, Max Nettlau (1865-1944). Below, I reproduce excerpts from a biographical sketch of Guillaume that Nettlau wrote in 1935, in which he sets forth some respectful criticisms of Guillaume’s claim that revolutionary syndicalism constituted the true heir to Bakunin’s revolutionary legacy.

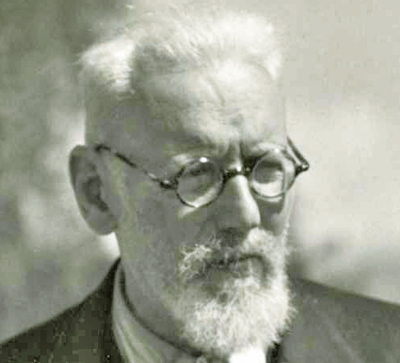

Max Nettlau

Max Nettlau: James Guillaume – A Biographical Sketch

This relatively little remembered man was on the side of Bakunin and, of course, many other comrades, the most efficient actor of those in the old International who resisted the will of Marx, [which leads] to social democracy, reformism and bolshevism, and affirmed complete libertarian socialism, expressed by anarchist thought and, to a certain degree, by revolutionary syndicalism…

[In Locle, Switzerland, during the early 1860s, Guillaume,] in looking round, in observing the local working population, by reading socialist and advanced philosophical books, by frequenting an old local revolutionist of strong social feelings, Constant Meuron, found consolation in devoting himself to educational work for the people… He read Feuerbach, Darwin, Fourier, Louis Blanc, Proudhon; he emancipated himself entirely from metaphysics, felt interested in what he heard of the French cooperators (an effort then supported in a broad spirit by Elie and Elisée Reclus, etc.), and of the International, of which in the larger township nearby, at La Chaux-de-Fonds, a section had already been founded.

In August 1866, Guillaume, old Meuron and a small handfull of others founded another section [in] Locle and in September, Guillaume represented it at the first Congress of the International, held in Geneva. There he met French, Belgian, British and other delegates and had his first direct glimpse at several of the social and labour currents of that times.

The activities of Guillaume, beginning in this small and new section [of the International], yet show him gradually coming to the front in the then small Jurassian milieu as a man who had a solid basis of general socialist information, who was penetrated by the wish to establish fraternal relations all over the awakening world of labour, but who could not imagine that such relations could be based upon any other basis than that of mutual fraternity and solidarity, of equality and of autonomy, non-interference with local life.

He had no idea that a Karl Marx resided in London who had the ambition to impress his own ideas upon the association, nor that a Central or General Council could be under the impression [that it could] be some organ of authority in the association, nor that parties, cliques, coteries could be formed and that locally useful and efficient men would try to extend their influence over districts, provinces and regions. All this was, in his opinion, exactly what the International did not wish to be; it was found[ed on] solidarity, respecting autonomy, and had no call to be a doctrinaire or an administrative unifying authority.

Guillaume was far from being an anarchist then and, in the real sense he was this always as we shall see. He had not broken with politics, [but] he had not made an effort to enter a political career. He had lived in politics all his life, seeing his father, a professional politician and office holder, and this gave him some inside experience and created the strong wish not to have to court the favour of the electors year by year, as his father had to do.

He had watched closely, French and Italian popular and insurrectional movements – the continuous struggles against Napoleon III, the usurper, and against the Bourbons, the Pope and the Austrians in Italy, and he was observing with curiosity the English trade unionists, the German Lassalleans, the Russians of Tchernychevski’s time. All interested him and he loved and admired many things but he never wished to introduce artificially outside ideas and tactics into the Jurassian milieu. In this respect already Geneva and Lausanne, much more Berne and Zürich, were already, one might say, foreign continents to him. He did not dream of recommending Jurassian methods anywhere outside the mountain district, nor did he wish or tolerate that outsiders should interfere with the Jura.

By and by he concluded that the Internationalists of Belgium were least of all disposed to impose their ideas either by propaganda or by authority (majorities, administrative power) upon others, and he was on the best possible terms with them, notably with Caesar de Paepe. Later, as Paris always attracted him as the mother of Revolutions, he conceived great admiration for [Eugene] Varlin, who was equally disposed to feel fullest international solidarity, but to maintain the autonomy of Parisian tactics.

As for Bakunin, his idea of a… sweeping, all-[embracing] revolution was always strange and unnecessary and seemed to be improbable to Guillaume, who reserved the Jurassian autonomy before everything. Bakunin was of ripe experience and fully understood Guillaume and abstained with tact and care from all that might mean to be an infringement upon that autonomy. This brought about and safeguarded their close cooperation of several years, mainly from 1869 to 1872.

Marx was incapable [of] conceiv[ing] the notion of autonomy, just as Lenin later scorned the bourgeois notion of freedom and so, with all respect for his economic learnedness – Bakunin and Guillaume were the two only men in Switzerland who had read Das Kapital of 1867 in the years following, about 1869-1870 – it was impossible for them to cooperate with him (Marx) in the International as he (Marx) scorned and flouted Bakunin’s highest ideal – Freedom – [and] Guillaume’s ethical basis – Autonomy.

Guillaume, then, had a life [of] purpose before himself, at twenty two, to cooperate internationally and locally in the reconstitution of socialism which had so languished in the nearly twenty years of reaction and apathy intervening since 1848. He was in what he considered an independent local position of not elementary but almost high school teaching, and further educational and political advancement (by elections) was within his grasp. But he did nothing to promote such a career; when he understood that taking part in elections was of no social value to the workers, he and his friends proclaimed abstention from politics, and when his militant socialism and local independence were considered by the authorities incompatible with his employment as a public school-professor, he did nothing to bow before the storm and was in due form [made destitute] in 1869, aged twenty five, walking out of office as a well read young man, soon to be married, but with no earthly goods and prospects, locally a marked man. So he remained throughout a long life, always having to shift for himself.

He had no precarious resource at hand [but only] another dim light in the sky… his old plan to live in Paris and this had been nourished by his close contact with Ferdinand Buisson, lecturing in 1869 in Switzerland on the subject of a renewed liberal Christianity, left-wing Protestant Rationalism. Both he and Guillaume were deeply interested in tearing elementary education in France from the hands of the Catholic clergy, of laïcising and improving it, and as Buisson was a staunch republican, his counsel would be listened to when that party would triumph over Napoleon III, and then he and Guillaume would cooperate as educational Robespierres, so to speak. This, they planned about 1869, and some of this they were able to realize between ten and twenty years later, indeed.

But meanwhile, to get a living, he came to a business arrangement with his unsentimental father, who was furious to see him lose his professional position. [His] father had a little printing office, badly managed at the time, and this James took over, investing money of his wife, and thus from August 1869 to the end of 1872, he kept this small business going, managing, reading proofs, setting up type himself sometimes, employing confidential compositors, keeping up punctual business relations with his father, while many less punctual relations where on his own shoulders. For here papers and pamphlets for the movement, international books, some Italian printing, all in the interest of the Swiss, French, Italian movements, were printed and sometimes work requiring caution and meeting with difficulties in distribution.

At other times, unskilled, helpless refugees would learn composing there. This little office at Neuchâtel was a real oasis of international printing for some time, one of the very few places at that time where work was efficiently done which defied equally Napoleon III, Bismarck, the Tsar and the Pope – and Karl Marx, Liebknecht and all the capitalists, and where Bakunin, the refugees of the Commune, Kropotkin (a visitor in 1872), the Italian and Spanish internationalists anarchists and the Jura Swiss workers felt at home. It required intense work and care on Guillaume’s side to keep this place going with real efficiency and evading absolute financial disaster. He was finally unable to continue his own overlarge mixture of intellectual, business, routine and often manual occupations and felt relieved when his father sold the printing office (end of 1872) and from then to the spring of 1878 he had to make a living in Neuchâtel by private lessons, many small paid translations and [by] beginning literary work for encyclopedic publications in Paris and London.

The situation [facing] him in 1877-1878, however, was so little hopeful, locally, that then, finally, in may 1878 he carried out his plan to go to live in Paris. He had been preparing to do this in the beginning of 1871, already, on the invitation of Buisson, but the Commune had intervened and the years of full reaction in France had made it quite impossible…

The watchmakers in Geneva and in the small Jurassian townships and large villages were up to the second half of the 1870s, when American machine-made watches and similar factories established also in Switzerland, ruined them and made them slaves to machinery – they were until then a very independent home-industry, very skilled work was done by men in their own rooms of small houses ; the demand for their output was universal and constant, they were used to combining against the large firms, they were citizens interested in local politics, some of them in social questions, they were not proletarianized at all and many of them welcomed the International and formed sections which were meant at first to be local educational units, forming local electoral power [distinct] from the bourgeois, agricultural, conservative and other interests.

In Geneva, the electoral power of these skilled workers was so great that the International sections – except the one inaugurated [in] 1868 by Bakunin (the Section of the Alliance) – never emancipated themselves from the politicians. In the Jura (the cantons of Bern and Neuchâtel mainly), the other electoral powers were stronger, and those of the International sections who had expected to further socialist aims by electoral methods, by local politics, saw that they were powerless after all at the elections. The same experience was [had] by a number of militant workers and citizens in Geneva who had tried to form a more advanced workers’ party and had failed at the elections of the autumn of 1868. Thus about that time these two milieus of socialists abandoning electoral politics had been formed – that of Guillaume in the Jura and that of [Charles] Perron in Geneva – and that very summer, about July, Bakunin had entered the International at Geneva – and he made the acquaintance of Perron in August and that of Guillaume at the end of the year; from then, for some time, these three men cooperated intimately.

Before this, Guillaume had assisted at the international Congresses of Geneva (1866) and Lausanne (1867), [being] most interest[ed] in the company of some Belgians, notably De Paepe, of some London and Paris delegates, informing himself on trade unionism, Parisian Proudhonism, meeting Dr. Ludwig Büchner, the author of “Kraft und Stoff”, the old German socialist Johann Philipp Becker; he corresponded with Hermann Jung, the Swiss secretary of the General Council, talked with Eccarius, a German tailor of London who was to some degree in the confidence of Karl Marx, etc.

All that interested him, just as he had met before old Fourierists in the Jura, old Pierre Leroux himself and others. And he was [one] of the delegates sent by the Lausanne Congress to the Peace Congress of Geneva (September 1867), where he saw Garibaldi and first saw and heard Bakunin, though not making his personal acquaintance. [That] took place at the congress held at the end of 1868 in Geneva, for the purpose of federating the French-speaking sections of Switzerland, to form the Fédération Romande.

He was standing out by his earnest activity and his skill as a clear debater and writer, and this may have contributed to making Bakunin wish to see more of him. In any case, as the outside delegates lodged with comrades in Geneva, it may not have been quite an accident that the young professor from the Jura was invited to lodge with Bakunin and in this way they became friends, and Guillaume was eager to invite Bakunin to come to the Jura, and Bakunin was quite satisfied to extend his sphere of activity to this new ground, thus taking up his position both in Geneva and in the milieu of the [Jura] Mountains.

Bakunin’s visits in the Jura (February and May 1869), short as they were, were time well spent in local manifestations affirming the independence of the sections from powerful politicians who propagated an adulterated socialism which was just some petty reformism, with more intimate, cordial discussions with many workers, with very intimate revolutionary discussions with a number of militants who shaped the activities of their whole lives, in not a few cases, upon these early impressions – and in conversations of the fullest confidence with Guillaume and but a very few others.

Bakunin (as we know) always had in view this: to inspire a small number of men of real value and efficiency with the whole of the anarchist ideas and the desire for action and these would each operate upon the best men of their acquaintance and confidence – and these upon a wider milieu of [the] less advanced, and so on. The most intimate would consult among themselves and consult with Bakunin, who was in a similar way in touch with efficient men of a number of other countries – and thus, by personal contact, correspondence, some travelers, the meeting of these intimates during congresses, etc., all these men could co-operate upon similar lines, albeit locally modified, and such private mutual understanding would harmonize the propaganda, create local milieus disposed to act upon similar lines and, someday, when action was possible and imminent, would facilitate it efficiently.

“Action” was not an idle dream in those years (1864-1870), of Bakunin’s impulse in this direction, as in at least three countries (France, Italy, Spain) rotten powers were doomed to fall – Napoleon III, the Pope as sovereign of the Roman State [Kirchenstaat], and Queen Isabella of Spain – and indeed Isabella fell in September 1868, and both Napoleon III and the Pope’s power over Rome fell in September 1870.

In Spain followed a revolutionary period lasting up to the end of 1874, including a Republic and the great insurrection of the federalist republicans of 1874. In France the accumulated [discontent] led to the two months of the Commune of Paris, March to May 1871, and in Italy, Garibaldi, straight from the Geneva congress of 1867, went to fight the Popish army in open battle and, after his failure, three years later the Italian army fought Rome and reduced the Pope to living from that time onward – until Mussolini’s surrender – in the Vatican, nominally declaring himself to be a prisoner.

Here we have all elements of revolutionary warfare – the Commune defying the French State and the French bourgeoisie, the insurgent Spanish cities proclaiming their autonomy, the Church of Rome bombarded by the Italian army and many other events – and if in all these the popular forces, the workers, did not succeed and were even terribly defeated and massacred (Paris), surely it was neither a chimerical and idle or absurd, nor a useless, unpractical thought and effort of Bakunin to try to prepare and to coordinate forces which should be ready to act on such occasions. His activities were strongest just in these countries and, if he failed, if he and his comrades could not overcome all the enormous obstacles, the blame may be laid on them for this or that mistake, but it lays much more upon all those who did not help them and it lays heaviest upon those who did all they could to combat, to discredit, to destroy them: here lays one of the various culpabilities which Marx accumulated during his career.

Marx, in those years, wielding the power which, he imagined, his participation in the General Council of the International had legitimately given to him, was haunted by the idea of war against Russia in favour of Poland and a secondary thought of Irish rebellion in England, while he also, after the easy victory of Prussia over Austria in 1866, was [impressed] by Bismarck’s prestige and had but contempt for France, Italy and Spain. None of his then expectations were realized while Bakunin, as to the West and South of Europe, had seen clearly. When Bakunin tried to rally the revolutionists in preparation [for the] very struggles which did come, Marx insisted [on starting] electoral labour parties, as Lassalle had done, and urged upon the States to begin the world war against Russia. So his fraction of the International became emasculated and he used the very nominal powers confided to the General Council to make regular war by chicanery and other means against the autonomous sections and federations [of the International].

This was keenly felt by an autonomist like Guillaume and welded him and Bakunin together until autonomy had triumphed in 1872-1873. But Guillaume was not [amenable] to Bakunin’s favorite attempt, to give to his relations with the intimate comrades a formal name, the Fraternité internationale, Alliance secrète or so, to write or even print statements of principles and rules, to correspond in cypher, etc. He practised the real thing, but rejected the form, and in this respect he was wiser then Bakunin who lost time in drawing up documents of such apparently conspiratorial character which, when misused, seized [and] published, gave an extraordinary aspect to very harmless things.

Bakunin knew that as well, but all the secret societies had such documents and some of the members seemed to like and to require it, while, in practice, very few or hardly any one conformed to such documents. Anyhow, Guillaume obtained from Bakunin in 1869 a general indulgence not to have anything to do with written rules himself, nor should Bakunin introduce them in the Jura. For the rest he did not care and he did exactly what Bakunin did (and had done before, locally) – he had incessant private relations with the militants in the Jura and he corresponded with all the intimates of Bakunin abroad, whenever necessary, without using the terms of any secret body (Fraternité, Alliance). He was most eager to attract militants in France within this inner sphere and came to some understanding with Varlin during the Congress of Basel (1869), etc. He was at times most painstaking to arrive at agreements by discussion, while when he considered that the occasion required immediate or modified action, he took it on as his sole responsibility.

Two examples of this are the manifesto of September, 5, 1870 in Neuchâtel, when upon the first news of the collapse of the Empire in Paris (September 4), he was misled to consider this political change a social revolution and called [on] all to take up arms to defend the Revolution in France. The Swiss government had this Manifesto seized and suppressed the paper, Solidarité, and Guillaume’s father felt anxiety about the printing plant which belonged to him. Bakunin wrote a most generous letter on that occasion to the Committee of the Fédération Romande, in defence of Guillaume’s over rash act on his personal account which deprived the organization [the Romande Federation] of its paper.

The other case happened at the Hague Congress, where an artificial majority, fabricated by Marx, Engels and others, expelled Bakunin and Guillaume from the International (September 1872). It had been agreed upon that the revolutionary federations should leave the congress, when the Marxist intrigue should unfold itself openly. Guillaume preferred to pass much time during the congress week to explain the situation to quite a number of non-revolutionists, but who were not friends of Marx either and who simply ignored the facts. In this way he formed a minority of revolutionists and general friends of fair play, and Marx turned yellow, when he saw to his surprise, that the revolutionists [did not] just leave, as he had expected, but that a declaration of solidarity by a strong minority was read, to which he had no reply to make.

Guillaume preferred an International composed of autonomous bodies of revolutionary or reformist, anarchist or social democratic, opinion, to a body composed exclusively of revolutionists. He did not object to such a body as the latter described, but he valued the principle of solidarity and autonomy expressed by the former composition – and so became the antiauthoritarian International of the St. Imier, Geneva, Brussels, Bern and Verviers congresses of the years 1872 (September) to 1877 (September). Bakunin formed intimate ties with the revolutionists at Zürich (September 1872), the Alliance of the Revolutionary Socialists (secret), but, after discussion with Guillaume, agreed with his tactics at the public Congress of St. Imier. A year later, in Geneva, Guillaume mainly shaped the new forms of the organization during a week of arduous discussion; Bakunin watched this from a distance, at Bern.

There is no question that the fall of the Commune in 1871 made Guillaume understand that socialism in France would not be revived in the spirit of his friend Varlin (who had been shot) for a long time to come, nor that the Hague congress, 1872, displaying all the malignity of Marx and Engels, made him see that socialism had that deleterious dry rot inside of it, Marxism – an emasculating disease which from then [on] has produced some fifty years of social democracy and [then] communist despotism in Russia. Both hard facts made Guillaume concentrate on Swiss local socialist autonomy and he had no real faith in revolutionary attempts as these were [being] prepared in Spain and in Italy by the fervent young Internationalists, and by Bakunin who, hopeful or hopeless, was active up to 1874.

Otherwise expressed – Guillaume considered his association with Bakunin more or less [had] come to an end, as the fight in common against Marx was over, as there was nothing to do in France, for some time, and as the Russian, Italian [and] Spanish activities of Bakunin did not concern him, while Bakunin was less interested than he in Belgian, British, Swiss, German and other movements. It came to this, sorry to tell, that while Bakunin continued to value what Guillaume did, the latter, who saw and heard little of Bakunin in 1873-74, came to imagine that Bakunin’s career was coming to an end. I cannot enter into this delicate subject [but] let it be sufficient to say here that at a moment in the autumn of 1874, when Bakunin would most have needed a clear thinking and fair-minded friend as Guillaume might have been to him, Guillaume proved utterly prejudiced, hard and cruel, and there was an absolute separation between Guillaume and several others and Bakunin (September 1874), and this remained so up to Bakunin’s death [in] 1876…

In this way Guillaume’s relations with Bakunin had a bitter end; [once again] a Robespierrist mind was unable to understand a Dantonesque character and felt obliged to try to destroy it.

That same autumn Guillaume wrote, at the invitation of Cafiero, an exposé of the social arrangements in a free society, a text published in 1876 as Idées sur l’Organisation sociale (Ideas on social organization), Chaux-de-Fonds, 1876, 56 p. – a clear statement of the collectivist anarchist conception with its eventual evolution toward communist anarchism; there were Italian and Spanish translations…

He had analysed Proudhon’s Confession of a Revolutionary, adding a description of mutualism and of collectivist anarchism, a book of which only a Russian translation (Anarchy according to Proudhon) exists in print, set up and printed by M.P. Sazin, in London, 1874 : the French manuscript is lost. He lectured on the French Revolution and printed sketches of great historical days in the Bulletin [of the Jura Federation]. He wrote also a study of the conspiracy of Babeuf. The Bulletin is very exact in foreign notes which he translated often from letters or took from secretly printed Spanish and other publications. The more one is able to inspect documentary relics of those years, the more there are traces of Guillaume’s constant care, resourcefulness and husbanding of very small means.

He was really masterful in exposing the Marxist protagonists, Engels, Lafargue, Greulich, etc. ; but he always tried to be on terms of polite correction with those who showed respect for autonomy toward the Jurassians, like some of the German Lassalleans and some less narrow socialists in Switzerland, in England, etc. But he kept out such as would adulterate and mix up the ideas like Benoît Malon and others of his ilk.

Kropotkin was greatly impressed by Guillaume on his first visit to him in the spring of 1872 and visited him again, [at the] end of 1876 (after [Kropotkin’s] escape from Russia), and saw him frequently in 1877 when [Kropotkin] had settled himself in the Jura. At that time, Paul Brousse, a French Southerner from Montpellier, was doing advanced and lively popular anarchist agitation in Bern and in the Jura, was best liked by the young people, while the elder generation preferred the sedate Guillaume. Kropotkin stood nearer to Brousse, but had a very great respect for Guillaume.

Brousse inspired the Red Flag procession in Bern, assaulted by the Gendarmes, when all the Jurassian and French militants and a number of Russians, Kropotkin as well as Plechanov, were in a hand-to-hand fight, with or without all sorts of weapons, implements and fists; and letters, recollections and the report of the ensuing trial still record who smashed up with gendarmes or was himself almost battered to pieces or was rescued by the intervention of the other comrades. There was a big trial in the autumn and 20 or 30 had to pass weeks or months that winter in the Jura prisons. They entered there in procession with the red flag (permitted there) and music and had their watchmakers’ table and tools brought into prison… Guillaume arrived with cases of books and papers and did his literacy work as before.

He had last seen the Internationalists at their private meeting at La Chaux-de-Fonds where also a large Jurassian congress was held; also a small and private French congress. Then he assisted at the Verviers congress [of the reconstituted International] in Belgium, with Viñas and Morago from Spain, Costa, Brousse, Kropotkin, Emil Werner, the Belgians; and at the so-called “World Socialist Congress,” held at Gent: here Liebknecht and Guillaume confronted [each other] and all the efforts of Guillaume to bring about a state of mutual toleration between the authoritarians and the libertarians – he had acted in that spirit at the International’s Bern Congress of 1876 – were frustrated by Liebknecht.

Thus, he was active to the last, but his material situation was locally hopeless, while a more efficient collaboration in Buisson’s large Dictionnaire de Pédagogie (Paris, Hachette) was possible only if he were settled in Paris. The Bulletin was succumbing – [at the] end of March 1878 – as the great crisis in the Jura (American competition by machinery) was approaching. In May, Guillaume went to Paris, having before resigned membership in the International, as this was a society prohibited in France.

The French liberal revival had begun by the elections early in 1876, but clerical governments still held power and James Guillaume imposed [on] himself the strictest incognito and abstained from participation in propaganda. Just then, Costa, who took no precautions, was arrested and heavily sentenced, and Kropotkin in connection with this had had to leave Paris and France. Later, [in] 1879, when Caferio and Malatesta, released from Italian prisons, came to see Guillaume, he was not exactly glad to receive the two romantic figures in his quiet home and so, by and by, he hinted to all visitors that they had better not come again and years of voluntary solitude followed…

[In the early 1900s], when he had discovered French Syndicalism, [Guillaume’s] purpose became to inform the syndicalists of the real work and spirit of the International as, unknown to most of them, they were in Guillaume’s opinion, its direct continuators…

Guillaume identified the ideas and aims of the collectivist International with those of Revolutionary Syndicalism – and he considered Communist Anarchism, the work of Reclus, Kropotkin, Malatesta etc., as an aberration, a period of time lost (1878-94) – and since 1895, more so since 1900 and 1904, the C.G.T. [the French revolutionary syndicalist organization, the General Confederation of Labour] had resumed in his opinion the old work of the International…

We are often told that the anarchist period in France, let us say the years 1880 to 1894 were a period of illusions: but if that were the case, the 1895 to 1906 and 1914 period of syndicalist illusions was infinitely more deceptive. With the workers by millions abandoning socialism for politics (social democracy), it was inevitable and logical on their part to abandon revolutionary syndicalism for reformist labourism (ouvrièrisme) and so they did, and the syndicalist leaders could not stay that current [stem that tide], but continued to proclaim the syndicalist ideology. They all knew that they were painting red the white cheeks of a corpse.

Only old James Guillaume did not wish to see things in their real light, and in the midst of reformism chose to believe to march ahead with an invincible revolutionary current impelling them all. It was pathetic to see the wish and the will of the old man not to see things as they were. To him, the syndicalists were the men of 1792 who when roused, as the events of 1914 – the war – might have done, would once more conquer Europe for freedom as the sansculottes of 1792 had meant to do – and when nothing of the kind happened, when the truth confronted him that summer [of 1914], within six months he had become a wreck and his life was nearly over, as we shall learn soon.

Meanwhile, from 1903-4 onward, he was “an Internationalist” by himself, entering into contact with the most suitable elements which he could find, trying to make them work together and like a spider, whose webs are almost constantly destroyed in part, he was undismayed by failure, always patched up the webs, but it told upon his nerves, he became bitter and in 1914 the open struggle by him against anarchism, as expressed by men like Bertoni and Malatesta, was only averted by [the] great efforts of Kropotkin…

Two factors stood in the way of any real success of his ceaseless activity. One was his absolute separation from the movements [for the preceding] 25 years. This meant that even those whom he knew intimately up until 1878, had changed, sometimes greatly developed, sometimes the contrary. He attributed to his old friends qualities which they had long since lost and – it was touching to see this – he imagined to see such qualities even in their grown up children who were quite unable to come up to his expectations…

…[F]from those of Kropotkin’s letters to [Guillaume] which have survived, one sees their entire separation: for the one, anarchism (implying Communism), for the other the Syndicalist Society, were the next ideal aims and coming realities. Kropotkin never wished to work for a Syndicalist Totalism, and Guillaume saw but this and considered Anarchism as the dream of the workers of Lyons (notorious dreamers), of Kropotkin (with all the vagueness of wide Russia-Siberia in him), of Malatesta (a romantic Italian insurrectionist), of Elisée Reclus (of old Christian mysticism), etc. So Guillaume had, in France, only the syndicalist leaders as comrades in the domain of ideas and these – some of whom like Pouget and Griffuelhes before all he really admired – these men had their hard daily struggle before them and not a moment’s rest and not time to listen to his advice, nor any wish to take him into their counsels in a really solidary way.

For these anti-parliamentarians and anti-politicians had themselves as much or more of “politics” in hand as ministers or political leaders. They had to control their committees and the members of these, the delegates of the Syndicates, had to secure the support of the majority of members; all were confronted by a strong reformist opposition, by governmental manoeuvres, and they required all the science or the tricks of regular “bosses” to do this. Besides, in the years after 1908, the syndicalist leaders themselves ceased to believe in the direct action-methods and became reformists at heart – Léon Jouhaux, once an anarchist, from 1909 to the present the secretary of the C.G.T., is typical for these transformations – while before the main body of members, at the Congresses, in the papers, they still affirmed until the war of 1914 to be revolutionist. Now a man like Guillaume, could not [prevent], nor hinder all this and it was best for all sides that he should keep out of it…

He was in touch mainly with some comrades in the Jura, in Lausanne, Bern and Zürich, with [Anselmo] Lorenzo in Barcelona, with Alceste de Ambris in Lugano or in Italy; but, as I hinted at before, this influence was not lasting, as all these correspondents had more or less made up their minds and had their own irons in the fire. He dreamed of coordinating them, as his friends had been internationally in Bakunin’s time. But all this was ephemeral or barely begun, and he had great disappointments.

These arose also, inevitably, out of the second factor which I now shall mention. As those who know the history of the International are aware of, at some time, in 1869, it was suggested that that organization was already the framework or the embryo of the coming free society and others, in 1870, accepted this as an organizational dogma and, logically – if any totalitarian reasoning could be logical at all – it was concluded and resolved upon, that in each locality, district, region, only one such organizational unit can and must exist. If by differences of opinion, etc., two units were forming, one was considered and decreed to be wrong and was expelled or expelled the other unit.

Endless and useless quarrels ensued in several places, but the dogma of the one unit in one place was maintained. Consequently also the French syndicalists recognized one territorial C.G.T. which, on its side, internationally, would enter into friendly relations, “be on speaking terms,” only with one similar territorial association for each country. Now in Germany, Austria, Hungary, Switzerland, the Scandinavian countries, etc., such territorial organizations were all controlled by social democrats and were utterly reformist. Nonetheless, the only international contact which the C.G.T. cared to have, was that meeting every two years of the general secretaries of these great bodies – meetings where the French were faced by a compact body of social democratic adversaries… and which consisted only of mutual bickering and useless travelling expenses.

When the real syndicalist movements were founded in several countries, they looked to the C.G.T. to encourage and help them. But the C.G.T., linked up with the social democratic trade unions of other countries, did nothing to help these struggling new movements and, for instance, ignored their international Congress held in London in September 1913 – where the foundations were laid for what after the long war was founded as the present I.W.A – A.I.T. Guillaume could not alter this state of things, which made it so difficult for the new syndicalists of other countries to sympathize with the French C.G.T. when they saw it linked up with their most bitter local enemies, the social democratic unions. At the same time, Guillaume was opposed to the anarchist spirit in the syndicates and, both in Switzerland and in Italy, he was with those who were the adversaries of the most recognized anarchist promoters of syndicalism – of Bertoni, Borghi, etc. All this made his task always more hopeless.

This embittered him and made him on the one hand take sides with men who introduced national partiality in socialist discussion – I refer to the notorious French professor[Charles] Andler [1866-1933 – author of Le Socialisme impérialiste dans l’Allemagne contemporaine, dossier d’une polémique avec Jean Jaurès 1912-1913, and Le Pangermanisme, ses plans d’expansion allemande dans le monde, 1915]. On the other hand, he was at the bottom of the new dogma of syndicalist “automatism” (1913-14) which misused certain writings of Bakunin (mainly of 1869-1870). By this dogma, by merely becoming an organized worker, a worker is expected to become automatically a revolutionary syndicalist, a social revolutionist.

Bakunin, urging workers to enter into the International, had described in elementary writings, for publication, how a milieu of solidarity promotes social feelings and leads to social action, and may lead to final revolutionary activities. But, as Guillaume of all men knew best, Bakunin considered as essential efficient secret activities of militants of real mark, of the Alliance, and thus only revolutionary action, in his opinion, could be initiated, spread, coordinated, rousing the less developed members and reaching masses of men.

Guillaume was free to proclaim “automatism”, but he had no right to say that Bakunin had advocated it; nor had he ever himself practiced it in the Jura, where he and his nearest friends always had been the initiators of everything, the men who on certain days met in a little known locality and arranged everything among themselves. Malatesta in Volontà pointed out the real facts and said that Guillaume better than anybody knew that Bakunin and his near comrades practiced the Alliance-method. So did Kropotkin who, when he was really militant, was the secretary of the intimate circle and who believed in this method, while, of course, he would not discourage spontaneity in public utterances.

The revolutionary activities of the workers are so slow in unfolding, that beginnings must be made by the very best developed – and if these beginnings can be reasoned out intelligently and co-ordinated as much as possible, so much the better – this is what Bakunin, Guillaume in his early days (and in practice to the last), Malatesta, and Kropotkin meant and tried to do. Automatism in this domain would mean revolutionary parthenogenesis or self-combustion (as in wet haystacks): that may happen, but when other initiating methods exist, why deny, reject, belittle, ignore them? That controversy of the first months of 1914, when Guillaume was especially hard on Bertoni, who was combating that other weak side of syndicalist organizations, the inevitable reformism and conservativism of paid functionaries, was brought to an end by private letters of Kropotkin conjuring [imploring] Guillaume and Bertoni to give up public polemics. As to the question at issue, Kropotkin considered Guillaume to be in the wrong…

He was so absorbed by the inner life of the C.G.T. and his own writings and polemics, that the war took him by surprise, like many others; but then, from the first moment, it was to him the year 1792 come again; the regiments which he saw marching being to him like the old sansculottes, now the founders of Socialism and Syndicalism on the ruins of Marxism. He immediately wrote in this spirit in the Bataille syndicaliste almost every day for a few weeks. Then his eyes opened to the fact that it was all militarism and that the workers introduced nothing of their own, nothing socialist nor revolutionary, into what was being done and that they were quite powerless or inactive, the C.G.T. and all.

This was a terrible blow to him – he had believed that a working class power and will did exist in France and he now saw that this was not so. This did not in the least diminish his solidarity with the French cause in the war, but it broke his hopes and his spirit, if not his body. He went to Neuchâtel once more, in September, when many left Paris, and passed an uncomfortable time in Switzerland, returning to Paris in November. He still wrote in the Bataille until about January 1915, but a serious illness, badly defined, had struck him, and after a short recovery his state seems to have required in February or March 1915 that he should leave Paris for the last time, and he was then in a deplorable state of physical [depredation] and mental despair… he expired in the late autumn of 1916 in his native canton of Neuchâtel.

I do not regret to have spoken for this length of the life of this remarkable man, an intellectual worker of an intense painstaking working effort, as the most hardworking manual worker might claim for himself. With his qualities and the tenth part of his effort he might have acquired power and wealth in any other cause than the most advanced causes, those which he helped with absolute abnegation. Intellectual efficiency and personal self-effacement, patient co-ordination of forces for collective action, rejoicing in friends, free thought, study, a firm will were some of his qualities. Of his deficiencies I have said more than enough for the sake of historic truth, as far as I can see it. His long story ought to stimulate us to work and to study, without which we are less than nothing.

Max Nettlau, December 9, 1935

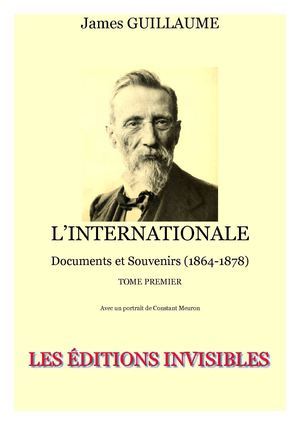

Guillaume’s documentary history of the International