- Order:

- Duration: 6:29

- Published: 05 Sep 2007

- Uploaded: 07 May 2011

- Author: gabberbaby69

(photo by Carl van Vechten).jpg)

.jpg)

crop.jpg)

3a.jpg)

_by_Erling_Mandelmann.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

![Construction of the Apex Building in 1937. In 1934, one building began construction and another finished. The Apex Building site began to be cleared in April.[144] The Post Office building was occupied on May 6,[145] and Postmaster General James Farley dedicated the Post Office Department building on June 11, 1934. Construction of the Apex Building in 1937. In 1934, one building began construction and another finished. The Apex Building site began to be cleared in April.[144] The Post Office building was occupied on May 6,[145] and Postmaster General James Farley dedicated the Post Office Department building on June 11, 1934.](http://web.archive.org./web/20110510041709im_/http://cdn.wn.com/pd/96/fe/495eae76225368e7d0d3f0a2a9d4_grande.jpg)

This text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.

| Name | Slavko Vorkapić |

|---|---|

| Image siz | 200px |

| Birth date | March 17, 1894 |

| Birth place | Dobrinci, Austria-Hungary |

| Death date | October 20, 1976 |

| Death place | Mijas, Spain |

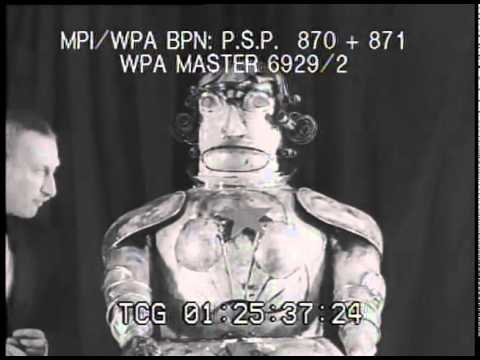

Vorkapić co-directed the experimental short film (1928) with Robert Florey, and Moods of the Sea (1941) and Forest Murmurs (1947) with filmmaker John Hoffman (1904–1980).

He is best known for his montage work (see montage sequence) on Hollywood films such as Viva Villa (1934), David Copperfield (1935), San Francisco (1936), The Good Earth (1937), and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939). In October 2005, the DVD collection was released and included a one-minute montage sequence Vorkapich did for the otherwise lost film Manhattan Cocktail (1928), directed by Dorothy Arzner.

The now-common montage sequence often appeared as notation in Hollywood scripts of the 1930s and 40s as the "vorkapich" because of his mastery of the dynamic visual montage sequence wherein time and space are compressed using a variety of editing techniques and camera moves. Vorkapich used kinetic editing, lap dissolves, tracking shots, creative graphics and optical effects for his stunning montage sequences for such features as Meet John Doe, Maytime, Crime without Passion, Manhattan Melodrama, and Firefly. He created, shot, and edited these kinesthetic montages for features at MGM, RKO, and Paramount.

His protege, Art Clokey, learned kinescope animation techniques under him and went on to create the Gumby animated series.

He was appointed dean of the USC School of Cinematic Arts of the University of Southern California from 1949-1951.

In 1938 Vorkapich commissioned modern architect Gregory Ain to build a garden house for his Beverly Hills residence. It was a minor landmark in prefabricated architecture. It has since been destroyed.

During the 1950s he was in Yugoslavia and worked as a professor at the Belgrade Film and Theatre Academy. In Yugoslavia in 1955 Vorkapić made his last full-length movie Hanka.

Slavko Vorkapić died of a heart attack in Mijas, Spain, on the estate of his son on October 20, 1976.

Two of his many master drawings, his gift during a visit to Yugoslavia, are kept in the Syrmia Museum in Sremska Mitrovica. Recent reports say that his descendants are ready to fulfill Vorkapić’s last will and testament to donate the same museum with all of his remaining art drawings.

Category:1894 births Category:1976 deaths Category:American people of Serbian descent Category:University of Southern California faculty Category:American film directors Category:American film editors Category:American cinematographers Category:Serbian film directors

This text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.

| Name | Sally Rand |

|---|---|

| Birth name | Helen Harriet Beck |

| Birth date | April 03, 1904 |

| Birth place | Hickory County, Missouri, U.S. |

| Death date | August 31, 1979 |

| Death place | Glendora, California, U.S. |

| Other names | Billie Beck |

| Occupation | Burlesque dancer Actress |

| Years active | 1925–1979 |

| Spouse | Clarence Robbins (?–?) Thurkel Greenough (1941–?)Harry Finkelstein (1949–1950) Fred Lalla (1954–?)}} |

Sally Rand (April 3, 1904 – August 31, 1979) was a burlesque dancer and actress, most noted for her ostrich feather fan dance and balloon bubble dance. She also performed under the name Billie Beck.

In 1936, she purchased The Music Box burlesque hall in San Francisco, which would later become the Great American Music Hall. She starred in "Sally Rand's Nude Ranch" at the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco in 1939 and 1940.

She appeared on television in 1957, on an episode of To Tell the Truth with host Bud Collyer and panelists Polly Bergen, Ralph Bellamy, Kitty Carlisle, and Carl Reiner. She did not "stump the panel" but was correctly identified by all four panelists. She continued to appear on stage doing her fan dance into the 1970s. Rand once replaced Ann Corio in the stage show, This Was Burlesque, appeared at the Mitchell Brothers club in San Francisco in the early 1970s and toured as one of the stars of the 1972 nostalgia revue "Big Show of 1928," which played major concert venues including New York's Madison Square Garden. Later, she appeared with Tempest Storm and Blaze Starr.

She was the model of several characters in Robert A. Heinlein's stories, such as the Mary-Lou Martin of "Let There Be Light". Rand was also included in Heinlein's final book, To Sail Beyond The Sunset, as a friend of main character, Maureen Johnson Long, mother of Lazarus Long.

Category:1904 births Category:1979 deaths Category:Actors from Missouri Category:American erotic dancers Category:American film actors Category:American silent film actors Category:Burlesque performers Category:Cardiovascular disease deaths in California Category:People from Jackson County, Missouri Category:People from New York City Category:Vaudeville performers

This text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.

| Name | Ethel Waters |

|---|---|

| Background | solo_singer |

| Born | October 31, 1896Chester, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | September 01, 1977Chatsworth, California, U.S. |

| Instrument | Vocals |

| Genre | Jazz, big band, pop, blues, rock and roll |

| Occupation | Actress, vocalist |

| Years active | 1925–1977 |

| Associated acts | Josephine BakerAlberta HunterBessie SmithFletcher Henderson |

Ethel Waters (October 31, 1896 – September 1, 1977) was an American blues, jazz and gospel vocalist and actress.

She frequently performed jazz, big band, and pop music, on the Broadway stage and in concerts, although she began her career in the 1920s singing blues. Her best-known recording was her version of the spiritual, "His Eye is on the Sparrow", and she was the second African American ever nominated for an Academy Award.

Waters married at the age of 13, but soon left her abusive husband and became a maid in a Philadelphia hotel working for US $4.75 per week. On Halloween night in 1913, she attended a party in costume at a nightclub on Juniper Street. She was persuaded to sing two songs, and impressed the audience so much that she was offered professional work at the Lincoln Theatre in Baltimore, Maryland. She later recalled that she earned the rich sum of ten dollars a week, but her managers cheated her out of the tips her admirers threw on the stage.

Waters loved a drug addict during this early period, but she ended the destructive relationship sometime before the war years. Around 1919 she moved to Harlem and there became a celebrity performer in the Harlem Renaissance during the 1920s.

Waters obtained her first job at Edmond's Cellar, a club that had a black patronage. She specialized in popular ballads, and became an actress in a blackface comedy called Hello 1919. The jazz historian Rosetta Reitz points out that by the time Waters returned to Harlem in 1921, women blues singers were among the most powerful entertainers in the country. In 1921 Waters became the fifth black woman to make a record, on the tiny Cardinal Records label. She later joined Black Swan Records, where Fletcher Henderson was her accompanist. Waters later commented that Henderson tended to perform in a more classical style than she would prefer, often lacking "the damn-it-to-hell bass". According to Waters, she influenced Henderson to practice in a "real jazz" style.

She recorded with Black Swan from 1921 through 1923. In early 1924 Paramount bought the Black Swan label, and she stayed with Paramount through 1924. Waters then first recorded for Columbia Records in 1925, achieving a hit with her voicing of "Dinah"—which recording was voted a Grammy Hall of Fame Award in 1998. Soon after, she started working with Pearl Wright, and together they toured in the South. In 1924 Waters played at the Plantation Club on Broadway. She also toured with the Black Swan Dance Masters. With Earl Dancer, she joined what was called the "white time" Keith Circuit, a traditional white-audience based vaudeville circuit combined with screenings of (then-silent) movies. They received rave reviews in Chicago, and earned the unheard-of salary of US$1,250 in 1928. In 1929, Harry Akst helped Wright and Waters compose a version of "Am I Blue?", her signature tune.

Although she was considered a blues singer during the pre-1925 period, Waters belonged to the Vaudeville-style style similar to Mamie Smith, Viola McCoy, and Lucille Hegamin. While with Columbia, she introduced many popular standards including "Dinah", "Heebie Jeebies", "Sweet Georgia Brown", "Someday, Sweetheart", "Am I Blue?" and "(What Did I Do To Be So) Black and Blue".

During the 1920s, Waters performed and was recorded with the ensembles of Will Marion Cook and Lovie Austin. As her career continued, she evolved toward being a blues and Broadway singer, performing with artists such as Duke Ellington.

She remained with Columbia through 1931. She then signed with Brunswick in 1932 and remained until 1933 when she went back to Columbia. She signed with Decca in late 1934 for only two sessions, as well as a single session in early 1938. She recorded for the specialty label "Liberty Music Shops" in 1935 and again in 1940. Between 1938 and 1939, she recorded for Bluebird.

In 1933, Waters made a satirical all-black film entitled Rufus Jones for President. She went on to star at the Cotton Club, where, according to her autobiography, she "sang 'Stormy Weather' from the depths of the private hell in which I was being crushed and suffocated." She took a role in the Broadway musical revue As Thousands Cheer in 1933, where she was the first black woman in an otherwise white show. She had three gigs at this point; in addition to the show, she starred in a national radio program and continued to work in nightclubs. She was the highest paid performer on Broadway, but she was starting to age. MGM hired Lena Horne as the ingenue in the all-Black musical Cabin in the Sky, and Waters starred as Petunia in 1942, reprising her stage role of 1940. The film, directed by Vincente Minnelli, was a success, but Waters, offended by the adulation accorded Horne and feeling her age, went into something of a decline.

in Stage Door Canteen (1943)]]

She began to work with Fletcher Henderson again in the late 1940s. She was nominated for a Best Supporting Actress Academy Award in 1949 for the film Pinky. In 1950, she won the New York Drama Critics Award for her performance opposite Julie Harris in the play The Member of the Wedding. Waters and Harris repeated their roles in the 1952 film version of Member of the Wedding In 1950, Waters starred in the television series Beulah but quit after complaining that the scripts' portrayal of African-Americans was "degrading." She later guest starred in 1957 and 1959 on NBC's The Ford Show, Starring Tennessee Ernie Ford.'' In the former episode she sang "Cabin in the Sky."

Despite these successes, her brilliant career was fading. She lost tens of thousands in jewelry and cash in a robbery, and the IRS hounded her. Her health suffered, and she worked only sporadically in following years. In 1950-51 she wrote the autobiography His Eye is on the Sparrow, with Charles Samuels. (It later was adapted for a stage production in which she was portrayed by Ernestine Jackson.) In it, she talks candidly about her life. She also explains why her age has often been misstated, saying that her mother had to sign a paper saying she was four years older than she was. She states she was born in 1900. In her second autobiography, To Me, It's Wonderful, Waters states that she was born in 1896.

Rosetta Reitz called Waters "a natural". Her "songs are enriching, nourishing. You will want to play them over and over again, idling in their warmth and swing. Though many of them are more than 50 years old, the music and the feeling are still there."

{| class=wikitable |- | colspan=5 align=center | Ethel Waters: Grammy Hall of Fame Award |- ! Year Recorded ! Title ! Genre ! Label ! Year Inducted |- align=center | 1929 | "Am I Blue?" | Traditional Pop (Single) | Columbia | 2007 |- align=center | 1933 | "Stormy Weather"(Keeps Rainin' All The Time) | Jazz (Single) | Brunswick | 2003 |- align=center | 1925 | "Dinah" | Traditional Pop (Single) | Columbia | 1998 |- align=center |}

Harlem Godfather: The Rap on my Husband, Ellsworth "Bumpy" Johnson (Paperback) by Mayme Hatcher Johnson (Author), Karen E. Quinones Miller (Author) (ISBN 978-0967602837)

Category:1896 births Category:1977 deaths Category:African American actors Category:African-American Catholics Category:African American singers Category:American female singers Category:American film actors Category:American gospel singers Category:American jazz singers Category:Burials at Forest Lawn Memorial Park (Glendale) Category:Classic female blues singers Category:Gospel Music Hall of Fame inductees Category:Jubilee Records artists Category:Mercury Records artists Category:RCA Victor artists Category:Vocalion Records artists Category:Musicians from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Category:People from Delaware County, Pennsylvania Category:Torch singers Category:Vaudeville performers

This text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.

| Name | Duke Ellington |

|---|---|

| Background | non_vocal_instrumentalist |

| Birth name | Edward Kennedy Ellington |

| Born | April 29, 1899Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Died | May 24, 1974New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Instrument | Piano |

| Genre | Orchestral jazz, swing, big band |

| Occupation | Bandleader, pianist, composer |

| Years active | 1914–1974 |

| Url | Duke Ellington Legacy |

A prominent figure in the history of jazz, Ellington's music stretched into various other genres, including blues, gospel, film scores, popular, and classical. His career spanned more than 50 years and included leading his orchestra, composing an inexhaustible songbook, scoring for movies, composing stage musicals, and world tours. Several of his instrumental works were adapted into songs that became standards. Due to his inventive use of the orchestra, or big band, and thanks to his eloquence and extraordinary charisma, he is generally considered to have elevated the perception of jazz to an art form on a par with other traditional genres of music. His reputation increased after his death, the Pulitzer Prize Board bestowing a special posthumous honor in 1999.

Ellington called his music "American Music" rather than jazz, and liked to describe those who impressed him as "beyond category". These included many of the musicians who were members of his orchestra, some of whom are considered among the best in jazz in their own right, but it was Ellington who melded them into one of the most well-known jazz orchestral units in the history of jazz. He often composed specifically for the style and skills of these individuals, such as "Jeep's Blues" for Johnny Hodges, "Concerto for Cootie" for Cootie Williams, which later became "Do Nothing Till You Hear from Me" with Bob Russell's lyrics, and "The Mooche" for Tricky Sam Nanton and Bubber Miley. He also recorded songs written by his bandsmen, such as Juan Tizol's "Caravan" and "Perdido" which brought the 'Spanish Tinge' to big-band jazz. Several members of the orchestra remained there for several decades. After 1941, he frequently collaborated with composer-arranger-pianist Billy Strayhorn, whom he called his "writing and arranging companion." Ellington recorded for many American record companies, and appeared in several films.

Ellington led his band from 1923 until his death in 1974. His son Mercer Ellington, who had already been handling all administrative aspects of his father's business for several decades, led the band until his own death in 1996. At that point, the original band dissolved. Paul Ellington, Mercer's youngest son and executor of the Duke Ellington estate, kept the Duke Ellington Orchestra going from Mercer's death onwards.

At the age of seven Ellington began taking piano lessons from Marietta Clinkscales. Daisy surrounded her son with dignified women to reinforce his manners and teach him to live elegantly. Ellington’s childhood friends noticed that "his casual, offhand manner, his easy grace, and his dapper dress gave him the bearing of a young nobleman", and began calling him Duke. Ellington credited his "chum" Edgar McEntree for the nickname. "I think he felt that in order for me to be eligible for his constant companionship, I should have a title. So he called me Duke."

Though Ellington took piano lessons, he was more interested in baseball. "President Roosevelt (Teddy) would come by on his horse sometimes, and stop and watch us play," he recalled. Ellington went to Armstrong Technical High School in Washington, D.C. He got his first job selling peanuts at Washington Senators baseball games.

In the summer of 1914, while working as a soda jerk at the Poodle Dog Cafe, he wrote his first composition, "Soda Fountain Rag" (also known as the "Poodle Dog Rag"). Ellington created "Soda Fountain Rag" by ear, because he had not yet learned to read and write music. "I would play the 'Soda Fountain Rag' as a one-step, two-step, waltz, tango, and fox trot," Ellington recalled. "Listeners never knew it was the same piece. I was established as having my own repertoire." In his autobiography, Music is my Mistress (1973), Ellington said he missed more lessons than he attended, feeling at the time that playing the piano was not his talent. Ellington started sneaking into Frank Holiday's Poolroom at the age of fourteen. Hearing the poolroom pianists play ignited Ellington's love for the instrument and he began to take his piano studies seriously. Among the many piano players he listened to, he listened to Doc Perry, Lester Dishman, Louis Brown, Turner Layton, Gertie Wells, Clarence Bowser, Sticky Mack, Blind Johnny, Cliff Jackson, Claude Hopkins, Phil Wurd, Caroline Thornton, Luckey Roberts, Eubie Blake, Joe Rochester, and Harvey Brooks.

Ellington began listening to, watching, and imitating ragtime pianists, not only in Washington, D.C., but in Philadelphia and Atlantic City, where he vacationed with his mother during the summer months.

From 1917 through 1919, Ellington launched his musical career, painting commercial signs by day and playing piano by night. Through his day job, Duke's entrepreneurial side came out: when a customer would ask him to make a sign for a dance or party, he would ask them if they had musical entertainment; if not, Ellington would ask if he could play for them. He also had a messenger job with the U.S. Navy and State Departments. Ellington moved out of his parents' home and bought his own as he became a successful pianist. At first, he played in other ensembles, and in late 1917 formed his first group, "The Duke’s Serenaders" ("Colored Syncopators", his telephone directory advertising proclaimed).

Ellington played throughout the Washington, D.C. area and into Virginia for private society balls and embassy parties. The band included Otto Hardwick, who switched from bass to saxophone; Arthur Whetsol on trumpet; Elmer Snowden on banjo; and Sonny Greer on drums. The band thrived, performing for both African-American and white audiences, a rarity during the racially divided times.

In June 1923 a gig in Atlantic City, New Jersey, led to a play date at the prestigious Exclusive Club in Harlem. This was followed in September 1923 by a move to the Hollywood Club – 49th and Broadway – and a four-year engagement, which gave Ellington a solid artistic base. He was known to play the bugle at the end of each performance. The group was called Elmer Snowden and his Black Sox Orchestra and had seven members, including James "Bubber" Miley. They renamed themselves "The Washingtonians". Snowden left the group in early 1924 and Ellington took over as bandleader. After a fire the club was re-opened as the Club Kentucky (often referred to as the "Kentucky Club"), an engagement which set the stage for the biggest opportunities in Ellington's life.

Ellington made eight records in 1924, receiving composing credit on three including Choo Choo. In 1925 Ellington contributed four songs to Chocolate Kiddies, an all-African-American revue which introduced European audiences to African-American styles and performers. "Duke Ellington and his Kentucky Club Orchestra" grew to a ten-piece organization; they developed their distinct sound by displaying the non-traditional expression of Ellington’s arrangements, the street rhythms of Harlem, and the exotic-sounding trombone growls and wah-wahs, high-squealing trumpets, and sultry saxophone blues licks of the band members. For a short time soprano saxophonist Sidney Bechet played with the group, imparting his propulsive swing and superior musicianship to the young band members. This helped attract the attention of some of the biggest names of jazz, including Paul Whiteman.

In 1927 King Oliver turned down a regular booking for his group as the house band at Harlem's Cotton Club; the offer passed to Ellington. With a weekly radio broadcast and famous white clientèle nightly pouring in to see them, Ellington and his band thrived in the period from 1932 to 1942, a golden age for the band.

Ellington was joined in New York City by his wife, Edna Thompson, and son Mercer in the late twenties, but the couple soon permanently separated. According to her obituary in Jet magazine, she was "[h]omesick for Washington" and returned (she died in 1967).

Although trumpeter Bubber Miley was a member of the orchestra for only a short period, he had a major influence on Ellington's sound. An early exponent of growl trumpet, his style changed the "sweet" dance band sound of the group to one that was hotter, which contemporaries termed 'jungle' style. He also composed most of "Black and Tan Fantasy" and "Creole Love Call". An alcoholic, Miley had to leave the band before they gained wider fame. He died in 1932 at the age of twenty-nine. He was an important influence on Cootie Williams, who replaced him.

In 1927 Ellington made a career-advancing agreement with agent-publisher Irving Mills, giving Mills a 45% interest in Ellington's future. Mills had an eye for new talent and early on published compositions by Hoagy Carmichael, Dorothy Fields, and Harold Arlen. During the 1930s Ellington's popularity continued to increase – largely as a result of the promotional skills of Mills – who got more than his fair share of co-composer credits. Mills arranged recording sessions on the Brunswick, Victor, and Columbia labels which gave Ellington popular recognition. Mills lifted the management burden from Ellington's shoulders, allowing him to focus on his band's sound and his compositions. Ellington ended his association with Mills in 1937, although he continued to record under Mills' banner through to 1940.At the Cotton Club, Ellington's group performed all the music for the revues, which mixed comedy, dance numbers, vaudeville, burlesque, music, and illegal alcohol. The musical numbers were composed by Jimmy McHugh and the lyrics by Dorothy Fields (later Harold Arlen and Ted Koehler), with some Ellington originals mixed in. Weekly radio broadcasts from the club gave Ellington national exposure. In 1929 Ellington appeared in his first movie, a nineteen-minute all-African-American RKO short, Black and Tan, in which he played the hero "Duke". In the same year, The Cotton Club Orchestra appeared on stage for several months in Florenz Ziegfeld's Show Girl, along with vaudeville stars Jimmy Durante, Eddie Foy, Jr., Al Jolson, Ruby Keeler, and with music and lyrics by George Gershwin and Gus Kahn. That feverish period also included numerous recordings, under the pseudonyms "Whoopee Makers", "The Jungle Band", "Harlem Footwarmers", and the "Ten Black Berries". In 1930 Ellington and his Orchestra connected with a whole different audience in a concert with Maurice Chevalier and they also performed at the Roseland Ballroom, "America's foremost ballroom". Noted composer Percy Grainger was also an early admirer and supporter.

In 1929, when Ellington conducted the orchestra for Show Girl, he met Will Vodery, Ziegfeld’s musical supervisor. In his 1946 biography, Duke Ellington, Barry Ulanov wrote:

As the Depression worsened, the recording industry was in crisis, dropping over 90% of its artists by 1933. Ellington and his orchestra survived the hard times by taking to the road in a series of tours. Radio exposure also helped maintain popularity. Ivie Anderson was hired as their featured vocalist. Sonny Greer had been providing occasional vocals and continued to do in a cross-talk feature with Anderson. Ellington, however, later had many different vocalists, including Herb Jeffries (until 1943) and Al Hibbler (who replaced Jeffries in 1943 and continued until 1951).

Ellington led the orchestra by conducting from the keyboard using piano cues and visual gestures; very rarely did he conduct using a baton. As a bandleader Ellington was not a strict disciplinarian; he maintained control of his orchestra with a crafty combination of charm, humor, flattery, and astute psychology. A complex, private person, he revealed his feelings to only his closest intimates and effectively used his public persona to deflect attention away from himself.

While the band's United States audience remained mainly African-American in this period, the Cotton Club had a near-exclusive white clientèle and the Ellington orchestra had a huge following overseas, exemplified by the success of their trip to England in 1933 and their 1934 visit to the European mainland. The English visit saw Ellington win praise from members of the 'serious' music community, including composer Constant Lambert, which gave a boost to Ellington's aspiration to compose longer works. For agent Mills it was a publicity triumph, as Ellington was now internationally known. On the band's tour through the segregated South in 1934, they avoided some of the traveling difficulties of African-Americans by touring in private railcars. These provided easy accommodations, dining, and storage for equipment while avoiding the indignities of segregated facilities.

The death of Ellington's mother in 1935 led to a temporary hiatus in his career. Competition was also intensifying, as African-American and white swing bands began to receive popular attention, including those of Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey, Jimmy Dorsey, Jimmie Lunceford, Benny Carter, Earl Hines, Chick Webb, and Count Basie. Swing dancing became a youth phenomenon, particularly with white college audiences, and "danceability" drove record sales and bookings. Jukeboxes proliferated nationwide, spreading the gospel of "swing". Ellington band could certainly swing, but Ellington's strengths were mood and nuance, and richness of composition; hence his statement "jazz is music; swing is business". Ellington countered with two developments. He made recordings of smaller groups (sextets, octets, and nonets) drawn from his then-15-man orchestra and he composed pieces intended to feature specific instrumentalist, as with "Jeep's Blues" for Johnny Hodges, "Yearning for Love" for Lawrence Brown, "Trumpet in Spades" for Rex Stewart, "Echoes of Harlem" for Cootie Williams and "Clarinet Lament" for Barney Bigard.

In 1937 Ellington returned to the Cotton Club which had relocated to the mid-town theater district. In the summer of that year, his father died, and due to many expenses, Ellington's finances were tight. Things improved in 1938 and he met and moved in with Cotton Club employee Beatrice "Evie" Ellis. After splitting with agent Irving Mills, he signed on with the William Morris Agency. The 1930s ended with a very successful European tour just as World War II loomed.

Ellington delivered some huge hits during the 1930s, which greatly helped to build his overall reputation. Some of them include: "Mood Indigo" (1930), "It Don't Mean a Thing (If It Ain't Got That Swing)" (1932), "Sophisticated Lady" (1933), "Solitude" (1934), "In a Sentimental Mood" (1935), "Caravan" (1937), "I Let A Song Go Out Of My Heart" (1938). "Take the "A" Train" which hit big in 1941, was written by Billy Strayhorn.

Strayhorn, originally hired as a lyricist, began his association with Ellington in 1939. Nicknamed "Swee' Pea" for his mild manner, Strayhorn soon became a vital member of the Ellington Organization. Ellington showed great fondness for Strayhorn and never failed to speak glowingly of the man and their collaborative working relationship, "my right arm, my left arm, all the eyes in the back of my head, my brain waves in his head, and his in mine". Strayhorn, with his training in classical music, not only contributed his original lyrics and music, but also arranged and polished many of Ellington's works, becoming a second Ellington or "Duke's doppelganger". It was not uncommon for Strayhorn to fill in for Duke, whether in conducting or rehearsing the band, playing the piano, on stage, and in the recording studio.

The band reached a creative peak in the early 1940s, when Ellington and a small hand-picked group of his composers and arrangers wrote for an orchestra of distinctive voices who displayed tremendous creativity.

Some of the musicians created a sensation in their own right. The short-lived Jimmy Blanton transformed the use of double bass in jazz, allowing it to function as a solo rather than a rhythm instrument alone. Ben Webster, the Orchestra's first regular tenor saxophonist, started a rivalry with Johnny Hodges as the Orchestra's foremost voice in the sax section. Ray Nance joined, replacing Cootie Williams (who had "defected", contemporary wags claimed, to Benny Goodman). Nance, however, added violin to the instrumental colors Ellington had at his disposal.

Three-minute masterpieces flowed from the minds of Ellington, Billy Strayhorn, Ellington's son Mercer Ellington, Mary Lou Williams and members of the Orchestra. "Cotton Tail", "Main Stem", "Harlem Airshaft", "Sidewalks of New York (East Side, West Side)", "Jack the bear", and dozens of others date from this period.

Privately made recordings of Nance's first concert date, at Fargo, North Dakota, on November 7, 1940 by Jack Towers and Dick Burris, are probably the most effective display of the band during this period. These recordings, later released as Duke Ellington at Fargo, 1940 Live, are among the first of innumerable live performances which survive, made by enthusiasts or broadcasters, significantly expanding the Ellington discography.

Ellington's long-term aim became to extend the jazz form from the three-minute limit of the 78 rpm record side, of which he was an acknowledged master. He had composed and recorded Creole Rhapsody as early as 1931 (issued as both sides of 12" record for Victor and both sides of a 10" record for Brunswick), and his tribute to his mother, "Reminiscing in Tempo," had filled four 10" record sides in 1935; however, it was not until the 1940s that this became a regular feature of Ellington's work.

In this, he was helped by Strayhorn, who had enjoyed a more thorough training in the forms associated with classical music than Ellington. The first of these, "Black, Brown, and Beige" (1943), was dedicated to telling the story of African-Americans, and the place of slavery and the church in their history. Ellington debuted Black, Brown and Beige in Carnegie Hall on January 23, 1943, beginning a series of concerts there suited to displaying Ellington's longer works. While some jazz musicians had played at Carnegie Hall before, few had performed anything as elaborate as Ellington’s work.

Unfortunately, starting a regular pattern, Ellington's longer works were generally not well-received. Jump for Joy, a full-length musical based on themes of African-American identity, debuted on July 10, 1941 at the Mayan Theater in Los Angeles. Although it had the support of the Hollywood establishment, and received mostly positive reviews, its socio-political outlook provoked a negative reaction among some members of the public. It ran for 122 performances until September 29, 1941, with a brief revival in November of that year. Its subject matter did not make it appealing to Broadway, despite Ellington's plans to take it there.

The settlement of the first recording ban of 1942–43 had a serious effect on all the big bands because of the increase in royalty payments to musicians which resulted from it. The financial viability of Ellington's Orchestra came under threat, though Ellington's income as a songwriter ultimately subsidized it. Ellington always spent lavishly and although he drew a respectable income from the Orchestra's operations, the band's income often just covered expenses.

The music industry's focus shifted away from the Big Bands to the work of solo vocalists such as the young Frank Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holliday and mainstream groups like The Andrews Sisters as World War II drew to a close. While Ellington had featured some of the most talented singers of the day fronting his orchestra, he and his band took a back seat to no one, which set him down a path that put him increasingly at odds with the growing recording industry which was profiting from celebrity singers who were cheaper to keep than a big band, and produced bigger revenues.

By the mid 1940s artists were creatively changing. One of Ellington's composer-arrangers, Mary Lou Williams, left Ellington in 1943 and by 1945 was working with Dizzy Gillespie on a new form of jazz music, "Bebop."

Bebop rebelled against mainstream jazz and the strict forms of which Ellington was perhaps its most well known standard-bearer. The music, which had redefined the American sound over 35 years, was about to be shaken up.

It would take another ten years for Bebop to begin catching on with jazz aficionados world-wide, but it was an early hit with club owners of smaller venues who could draw the jazz form's growing audiences in New York City at a fraction of the cost of hosting a big band, particularly one of Ellington's caliber. Newer, smaller bands and splinter forms of music increasingly put pressure on the bigger clubs who paid out increasingly more to maintain their big bands. Ellington's elite band was a costly enterprise that, along with his excessive personal spending, always teetered on the brink of break-even. The new music trends eventually pushed it over the edge and put Ellington out on the road in search of venues that could afford to showcase his music.

Bebop was also a huge shift for young talent, from Charlie Parker to John Coltrane to Thelonious Monk who did not embrace Big Band and sought out new creative frontiers, redefining "modern" jazz music forever. Ellington did not recruit or embrace these new artists and change with the times.

In 1950 another emerging musical trend, the African-American popular music style known as Rhythm and Blues driven by a new generation of composers and musicians like Fats Domino drew away young audiences from both the African-American and white communities, and ultimately unified those audiences as R&B; morphed into Rock & Roll which expanded the cults of the singers from the Big Band era to the singer/songwriters from Domino to Elvis Presley to Buddy Holly. Again, Ellington did not embrace the new musical form, leaving him further in the growing dust cloud of musical history.

Ellington continued on his own course through these tectonic shifts in the music business. He did not wholly resist trends while trying to turn out major works. The Kay Davis vocal feature "Transblucency" was an attempt to cater to the singer-centric music world. He still performed major extended compositions such as Harlem (1950), whose score he presented to music-loving President Harry Truman, but these works were rapidly becoming reflections of his greatness in the 1930s and 1940s, and not ground-breaking works that rattled the music world back into the Big Band camp.

In 1951, Ellington suffered a major loss of personnel, with Sonny Greer, Lawrence Brown, and most significantly Johnny Hodges, leaving to pursue other ventures. Lacking overseas opportunities and motion picture appearances, Ellington's Orchestra survived on "one-nighters" and whatever else came their way.

By the summer of 1955 the band was performing for six weeks at the Aquacade in Flushing, New York, where Ellington is supposed to have "invented" a drink known as "The Tornado," the only alcoholic concoction that features his signature Coca-Cola and sugar.

Ellington had hoped that television would provide a significant new outlet for his type of jazz was not fulfilled. Tastes and trends had moved on without him. The introduction of the 33 1/3 rpm LP record and hi-fi phonograph though, did give new life to many of his older compositions. However by 1955, after three years of recording for Capitol, Ellington no longer had a regular recording affiliation.

featured Ellington.]]

Ellington's appearance at the Newport Jazz Festival on July 7, 1956 returned him to wider prominence and exposed him to new audiences. The feature "Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue", with saxophonist Paul Gonsalves's six-minute saxophone solo, had been in the band's book since 1937, but on this occasion nearly created a riot. The revived attention should not have surprised anyone – Hodges had returned to the fold the previous year, and Ellington's collaboration with Strayhorn had been renewed around the same time, under terms more amenable to the younger man. Such Sweet Thunder (1957), based on Shakespeare's plays and characters, and The Queen's Suite, dedicated to Queen Elizabeth II, were products of the renewed impetus which the Newport appearance helped to create.

A new record contract with Columbia produced Ellington's best-selling LP Ellington at Newport and yielded six years of recording stability under producer Irving Townsend, who coaxed both commercial and artistic productions from Ellington. In 1957, CBS (Columbia's parent corporation) aired a live television production of A Drum Is a Woman, an allegorical suite which received mixed reviews. Festival appearances at the new Monterey Jazz Festival and elsewhere provided venues for live exposure, and a European tour in 1958 was wildly received.

After a 25-year gap, Ellington (with Strayhorn) returned to work on film scores, this time for Anatomy of a Murder (1959) and Paris Blues (1961). Ellington and Strayhorn, always looking for new musical territory, produced adaptations of John Steinbeck's novel Sweet Thursday, Tchaikovsky's Nutcracker Suite and Edvard Grieg's Peer Gynt. The late 1950s also saw Ella Fitzgerald record her Duke Ellington Songbook with Ellington and his orchestra—a recognition that Ellington's songs had now become part of the cultural canon known as the "Great American Songbook".

Detroit Free Press music critic Mark Stryker concludes that the work of Billy Strayhorn and Ellington in Anatomy of a Murder, the trial court drama film directed by Otto Preminger in 1959, is "indispensable, [although] . . . too sketchy to rank in the top echelon among Ellington-Strayhorn masterpiece suites like Such Sweet Thunder and The Far East Suite, but its most inspired moments are their equal." Film historians have recognized the soundtrack "as a landmark – the first significant Hollywood film music by African Americans comprising non-diegetic music, that is, music whose source is not visible or implied by action in the film, like an on-screen band." The score avoided the cultural stereotypes which previously characterized jazz scores and rejected a strict adherence to visuals in ways that presaged the New Wave cinema of the ’60s".

In the early 1960s, Ellington embraced recording with artists who had been fierce rivals of the past, or who had been young artists from the Bebop beginnings whom he didn't associate with. The Ellington and Count Basie orchestras recorded together. During a period when he was between recording contracts he made a records with Louis Armstrong (Roulette), Coleman Hawkins, John Coltrane (both for Impulse) and participated in a session with Charles Mingus and Max Roach which produced the Money Jungle (United Artists) album.

Ironically, the singer most responsible for setting off the changes that brought an end to the big band era became Ellington's salvation. He signed to Frank Sinatra's new Reprise label. Musicians who had previously worked with Ellington returned to the Orchestra as members: Lawrence Brown in 1960 and Cootie Williams in 1962.

The international mania for jazz reinstated Ellington as one of the highest earning artists in jazz. He performed all over the world; a significant part of each year was now spent making overseas tours.

He formed notable new working relationships with international artists from around the world, including the Swedish vocalist Alice Babs, and South African musicians Dollar Brand and Sathima Bea Benjamin (A Morning in Paris, 1963/1997).

His earlier hits became big sellers in the rediscovery of the music world-wide, earning Ellington impressive royalties.

"The writing and playing of music is a matter of intent.... You can't just throw a paint brush against the wall and call whatever happens art. My music fits the tonal personality of the player. I think too strongly in terms of altering my music to fit the performer to be impressed by accidental music. You can't take doodling seriously." His reaction at 67 years old: "Fate is being kind to me. Fate doesn't want me to be famous too young." In September of the same year, the first of his Sacred Concerts was given its premiere. It was an attempt to fuse Christian liturgy with jazz, and even though it received mixed reviews, Ellington was proud of the composition and performed it dozens of times. This concert was followed by two others of the same type in 1968 and 1973, known as the Second and Third Sacred Concerts. This caused controversy in what was already a tumultuous time in the United States. Many saw the Sacred Music suites as an attempt to reinforce commercial support for organized religion, though Ellington simply said it was, "the most important thing I've done." The Steinway piano upon which the Sacred Concerts were composed is part of the collection of the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History. Like Haydn and Mozart, Ellington conducted his orchestra from the piano - he always played the keyboard parts when the Sacred Concerts were performed.

from President Nixon, 1969.]] Ellington continued to make vital and innovative recordings, including The Far East Suite (1966), the New Orleans Suite (1970), and The Afro-Eurasian Eclipse (1971), much of it inspired by his world tours. It was during this time that Ellington recorded his only album with Frank Sinatra, entitled Francis A. & Edward K. (1967).

Ellington was awarded the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1966. He was later awarded several other prizes, the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1969, an Honorary PhD from the Berklee College of Music in 1971, and the Legion of Honor by France in 1973, the highest civilian honors in each country. At his funeral attended by over 12,000 people at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, Ella Fitzgerald summed up the occasion, "It's a very sad day. A genius has passed." Mercer Ellington picked up the reins of the orchestra immediately after Duke's death. Ellington's last words were, "Music is how I live, why I live and how I will be remembered."

He wrote an original score for director Michael Langham's production of Shakespeare's Timon of Athens at the Stratford Festival in Ontario, Canada which opened on July 29, 1963. Langham has used it for several subsequent productions, most recently in an adaptation by Stanley Silverman which expands the score with some of Ellington's best-known works.

Ellington composed the score for the musical Jump For Joy, which was performed in Los Angeles during 1941. Ellington's sole book musical, Beggar's Holiday, was staged on Broadway in 1946. Sophisticated Ladies, an award-winning 1981 musical revue, incorporated many tunes from his repertoire.

Ellington's sister Ruth (1915–2004) later ran Tempo Music, Ellington's music publishing company. Ruth's second husband was the bass-baritone McHenry Boatwright, whom she met when he sang at her brother's funeral.

Ellington's grandson Edward Ellington is a musician and maintains a small salaried band known as the Duke Ellington Legacy, which frequently comprises the core of the big band operated by The Duke Ellington Center for the Arts.

His son, Mercer Ellington kept his big band alive after his passing. When Mercer died, Paul Ellington kept the Duke Ellington Orchestra going. It plays in concert halls around the world to this day.

In Ellington's birthplace of Washington, D.C., there is a school dedicated to his honor and memory as well as one of the bridges over Rock Creek Park. The Duke Ellington School of the Arts educates talented students, who are considering careers in the arts, by providing intensive arts instruction and strong academic programs that prepare students for post-secondary education and professional careers. The Calvert Street Bridge was renamed the Duke Ellington Bridge; built in 1935, it connects Woodley Park to Adams Morgan.

On February 24, 2009, the United States Mint launched a new coin featuring Duke Ellington, making him the first African-American to appear by himself on a circulating U.S. coin. Ellington appears on the reverse ("tails") side of the District of Columbia quarter.

Ellington lived for years in a townhouse on the corner of Manhattan's Riverside Drive and West 106th Street. After his death, West 106th Street was officially renamed Duke Ellington Boulevard. A large memorial to Ellington, created by sculptor Robert Graham, was dedicated in 1997 in New York's Central Park, near Fifth Avenue and 110th Street, an intersection named Duke Ellington Circle.

Although he made two more stage appearances before his death, Ellington performed what is considered his final "full" concert in a ballroom at Northern Illinois University on March 20, 1974. The hall was renamed the Duke Ellington Ballroom in 1980. at 6535 Hollywood Blvd.]]

A statue of Ellington at a piano is featured at the entrance to UCLA's Schoenberg Hall. According to UCLA magazine, "When UCLA students were entranced by Duke Ellington's provocative tunes at a Culver City club in 1937, they asked the budding musical great to play a free concert in Royce Hall. 'I've been waiting for someone to ask us!' Ellington exclaimed".

"On the day of the concert, Ellington accidentally mixed up the venues and drove to USC instead. He eventually arrived at the UCLA campus and, to apologize for his tardiness, played to the packed crowd for more than four hours. And so, "Sir Duke" and his group played the first-ever jazz performance in a concert venue."

He is one of only five jazz musicians ever to have been featured on the cover of Time (the other four being Louis Armstrong, Thelonious Monk, Wynton Marsalis, and Dave Brubeck).

The Essentially Ellington High School Jazz Band Competition and Festival is a nationally renowned annual competition for prestigious high school bands. Started in 1996 at Jazz at Lincoln Center, the festival is named after Ellington because of the large focus that the festival places on his works.

There are hundreds of albums dedicated to the music of Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn by artists famous and obscure. The more notable artists include Sonny Stitt, Thelonious Monk, Dizzy Gillespie, Tony Bennett, Claude Bolling, Oscar Peterson, Toshiko Akiyoshi, Dick Hyman, Joe Pass, Milt Jackson, Earl Hines, André Previn, World Saxophone Quartet, Ben Webster, Zoot Sims, Kenny Burrell, Lambert, Hendricks and Ross, Martial Solal, Clark Terry and Randy Weston.

Martin Williams said "Duke Ellington lived long enough to hear himself named among our best composers. And since his death in 1974, it has become not at all uncommon to see him named, along with Charles Ives, as the greatest composer we have produced, regardless of category."

In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed Duke Ellington on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.

Andre Previn said, "You know, Stan Kenton can stand in front of a thousand fiddles and a thousand brass and make a dramatic gesture and every studio arranger can nod his head and say, ‘‘Oh, yes, that’s done like this.’’ But Duke merely lifts his finger, three horns make a sound, and I don’t know what it is!"

{| class=wikitable |- | colspan=5 align=center | Duke Ellington: Grammy Hall of Fame Award |- ! Year Recorded ! Title ! Genre ! Label ! Year Inducted |- align=center | 1932 | "It Don't Mean a Thing (If It Ain't Got That Swing)" | Jazz (Single) | Brunswick | 2008 |- align=center | 1934 | "Cocktails for Two" | Jazz (Single) | Victor | 2007 |- align=center | 1957 | Ellington at Newport | Jazz (Album) | Columbia | 2004 |- align=center | 1956 | "Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue" | Jazz (Single) | Columbia | 1999 |- align=center | 1967 | Far East Suite | Jazz (Album) | RCA | 1999 |- align=center | 1944 | Black, Brown and Beige | Jazz (Single) | RCA Victor | 1990 |- align=center | 1928 | "Black and Tan Fantasy" | Jazz (Single) | Victor | 1981 |- align=center | 1941 | "Take the "A" Train" | Jazz (Single) | Victor | 1976 |- align=center | 1931 | "Mood Indigo" | Jazz (Single) | Brunswick |1975 |- align=center |}

{| class=wikitable |- ! Year ! Category ! Notes |- align=center | 2009 | Commemorative U.S. quarter | D.C. and U.S. Territories Quarters Program. |- align=center | 2008 | Gennett Records Walk of Fame |- align=center | 2004 | Nesuhi Ertegün Jazz Hall of Fameat Jazz at Lincoln Center |- align=center | 1999 | Pulitzer Prize | Special Citation |- align=center | 1978 | Big Band and Jazz Hall of Fame |- align=center | 1973 | French Legion of Honor | July 6, 1973 |- align=center | 1973 | Honorary Degree in Music from Columbia University | May 16, 1973 |- align=center | 1971 | Honorary Doctorate Degree from Berklee College of Music |- align=center | 1971 | Songwriters Hall of Fame |- align=center | 1969 | Presidential Medal of Freedom |- align=center | 1956 | Down Beat Jazz Hall of Fame inductee |- align=center | 1968 | Grammy Trustees Award | Special Merit Award |- align=center | 1966 | Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award |- align=center | 1959 | NAACP Spingarn Medal |}

Category:1899 births Category:1974 deaths Category:African American musicians Category:American autobiographers Category:American jazz composers Category:American jazz pianists Category:Big band bandleaders Category:Columbia Records artists Category:Decca Records artists Category:Gennett recording artists Category:Red Baron Records artists Category:Grammy Award winners Category:Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award winners Category:Légion d'honneur recipients Category:Musicians from Washington, D.C. Category:Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients Category:RCA Victor artists Category:Songwriters Hall of Fame inductees Category:Swing pianists Category:American Episcopalians Category:Cancer deaths in New York Category:Deaths from lung cancer Category:Burials at Woodlawn Cemetery (The Bronx) Category:Spingarn Medal winners Category:American pianists

This text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.

| Name | Cole Porter |

|---|---|

| Alt | Caucasian man in his thirties smiling and looking into the camera. He has a round face, full lips and large dark eyes, and his short dark hair is combed to the side. He is wearing a dark jacket, a white shirt and a black tie with white dots. |

| Caption | Cole Porter, composer and songwriter |

| Birth date | June 09, 1891 |

| Birth place | Peru, Indiana, U.S. |

| Death date | October 15, 1964 |

| Death place | Santa Monica, California, U.S. |

| Spouse | (her death) |

Cole Albert Porter (June 9, 1891 – October 15, 1964) was an American composer and songwriter. His works include the musical comedies Kiss Me, Kate, Fifty Million Frenchmen, DuBarry Was a Lady and Anything Goes, as well as songs like "Night and Day", "I Get a Kick out of You", "Well, Did You Evah!" and "I've Got You Under My Skin". He was noted for his sophisticated, bawdy lyrics, clever rhymes and complex forms. Porter was one of the greatest contributors to the Great American Songbook. Cole Porter is one of the few Tin Pan Alley composers to have written both the lyrics and the music for his songs.

In 1948, Porter made a great comeback, writing his biggest hit show, Kiss Me, Kate. The production won the Tony Award for Best Musical (the first Tony awarded in that category), and Porter won for Best Composer and Lyricist. The score includes "Another Op'nin' Another Show", "Wunderbar", "So In Love", "We Open in Venice", "Tom, Dick or Harry", "I've Come to Wive It Wealthily in Padua", "Too Darn Hot", "Always True to You (in My Fashion)", and "Brush Up Your Shakespeare". Though his next show, Out Of This World (1950), was not greatly successful, the show after that, Can-Can (1952), featuring "C'est Magnifique" and "It's All Right with Me", was another hit. His last original Broadway production, Silk Stockings (1955), featuring "All of You", was also successful.

Meanwhile, Porter continued to work in Hollywood, writing the scores for two Fred Astaire movies, Broadway Melody of 1940 (1940), which featured an old hit, "Begin The Beguine," and a new one, "I Concentrate on You", and You'll Never Get Rich (1941). He later wrote the songs for the Gene Kelly and Judy Garland musical The Pirate (1948). The film lost money, though it features the standard "Be a Clown" (echoed in Donald O'Connor's performance of "Make 'Em Laugh" in the 1952 musical film Singin' in the Rain). High Society (1956), starring Bing Crosby, Frank Sinatra and Grace Kelly, had Porter's last major hit, "True Love".

Judy Garland performed a medley of Porter's songs at the 37th Academy Awards, the first Oscars ceremony held following Porter's death. Porter's life was made into Night and Day, a very sanitized 1946 Michael Curtiz film starring Cary Grant and Alexis Smith. His life was chronicled more realistically in De-Lovely, a 2004 Irwin Winkler film starring Kevin Kline as Porter and Ashley Judd as Linda. The Cole Porter Festival is held every year the second weekend of June, in his hometown of Peru, Indiana. The festival fosters music and art appreciation by celebrating Porter's life and music. In 1980, Porter's music was used for the score of Happy New Year, based on the Philip Barry play Holiday. He is referenced in the song "The Call of the Wild" (Merengue) by David Byrne on his 1989 album Rei Momo. He is also mentioned in the song "Tonite It Shows" by Mercury Rev on their 1998 album Deserter's Songs. At halftime of the 1991 Orange Bowl between Colorado and Notre Dame, Joel Grey led a large cast of singers and dancers in a tribute to Porter marking the one hundredth anniversary of his birth. The program was called, "You'll Get a Kick Out of Cole".

The French Foreign Legion honors Porter with a portrait that hangs in the Legion's official museum. Porter was a Steinway Artist, which means that he chose to perform on Steinway pianos exclusively, and he owned a Steinway piano. Porter's piano is currently in the lobby of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York City.

In December 2010, Cole Porter's portrait was added to the Hoosier Heritage Gallery in the office of the Governor of Indiana.

Shows listed are stage musicals unless otherwise noted. Where the show was later made into a film, the year refers to the stage version. A complete list of Porter's works is in the Library of Congress (Complete List of Cole Porter works, and Cole Porter Collection at the Library of Congress).

A far more comprehensive list of Cole Porter songs, along with their date of composition and original show, is available online at the "Cole Porter Songlist Page".

Category:1891 births Category:1964 deaths Category:Songwriters from Indiana Category:American film score composers Category:American musical theatre composers Category:American musical theatre lyricists Category:Musicians from Indiana Category:Deaths from renal failure Category:Grammy Award winners Category:LGBT composers Category:LGBT musicians from the United States Category:People from Peru, Indiana Category:People from Santa Monica, California Category:American amputees Category:Schola Cantorum de Paris alumni Category:Scroll and Key Category:Songwriters Hall of Fame inductees Category:Worcester Academy alumni Category:Yale University alumni Category:Harvard University alumni Category:Soldiers of the French Foreign Legion

This text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.

| Name | Carole Lombard |

|---|---|

| Birth name | Jane Alice Peters |

| Birth date | October 06, 1908 |

| Birth place | Fort Wayne, Indiana, U.S. |

| Death date | |

| Death place | Mount Potosi, near Las Vegas, Nevada, U.S. |

| Resting place | Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale, California |

| Spouse | William Powell (1931–1933; divorced)Clark Gable (1939–1942; her death) |

| Occupation | Actress |

| Years active | 1921–1942 |

Carole Lombard (October 6, 1908 – January 16, 1942) was an American actress. She was particularly noted for her comedic roles in several classic films of the 1930s, most notably in the 1936 film My Man Godfrey. She is listed as one of the American Film Institute's greatest stars of all time and was the highest-paid star in Hollywood in the late 1930s, earning around US$500,000 per year (more than five times the salary of the US President). Lombard's career was cut short when she died at the age of 33 in the crash of TWA Flight 3.

Lombard achieved a few minor successes in the early 1930s in 1930's Safety in Numbers with Charles "Buddy" Rogers and 1932's No Man of Her Own with Clark Gable, but she was continuously cast in second-rate films. It was not until 1934 that her career began to take off. That year, director Howard Hawks encountered Lombard at a party and became enamored with her saucy personality, thinking her just right for his latest project. He hired her for Twentieth Century, alongside stage legend John Barrymore. Lombard was at first intimidated by Barrymore, but the two quickly developed a good working rapport. The film bolstered Lombard's reputation immensely and brought her a level of fame that her previously lackluster career had eschewed her from. in Swing High, Swing Low (1937)]]

Also in 1934, she starred in Bolero with George Raft and it was for this film that she turned down the role of Ellie Andrews in It Happened One Night. In 1935 she starred in Mitchell Leisen's Hands Across the Table which helped to establish her reputation as a top comedy actress. 1936 proved to be a big year for Lombard with her casting in the screwball comedy My Man Godfrey alongside ex-husband William Powell. Her performance earned Lombard an Academy Award nomination for Best Actress. It was followed by Nothing Sacred in 1937, casting her opposite Fredric March and under the direction of William A. Wellman. It was Lombard's only film in Technicolor and was regarded a critical and commercial smash. Nothing Sacred put Lombard at the top of the Hollywood tier and established her one of the highest paid actresses in the business.

(1940).]] In 1938, Lombard suffered a flop with Fools for Scandal and moved on to dramatic films for the next few years. In 1939, Lombard took roles opposite James Stewart in producer David O. Selznick's Made for Each Other (1939) and Cary Grant in In Name Only (1939). She also starred in the dramatic Vigil in the Night in 1940.

Audiences did not respond as well to Lombard in dramatic roles and she made a return to comedy, teaming with director Alfred Hitchcock in Mr. & Mrs. Smith (1941). The film gave Lombard's career a much needed boost and she followed her success with what proved to be her last film, and one of her most successful, To Be or Not to Be (1942).

In 1934, following her divorce from Powell, Lombard moved into a house on Hollywood Boulevard. She lived with a friend from the days of Mack Sennett, Madalynne Fields, who became Lombard's personal secretary and whom Lombard called "Fieldsie." Lombard became known as one of Hollywood's great hostesses for her outrageous parties with unconventional themes. During this time she carried on relationships with actors Gary Cooper and George Raft, as well as the screenwriter Robert Riskin.

Also during 1934, Lombard met and began a serious affair with crooner Russ Columbo. Columbo reportedly proposed marriage, but was killed in a freak shooting accident at the age of 26. To reporters Lombard said Columbo was the love of her life.

Lombard's most famous relationship came in 1936 when she became involved with actor Clark Gable. They had worked together previously in 1932's No Man of Her Own, but at the time Lombard was still happily married to Powell and knew Gable to have the reputation of a roving eye. They were indifferent to each other on the set and did not keep in touch.

It was not until 1936, when Gable came to the Mayfair Ball that Lombard had planned, that their romance began to take off. Gable, however, was married at the time to oil heiress Rhea Langham, and the affair was kept quiet. The situation proved a major factor in Gable accepting the role of Rhett Butler in Gone With the Wind, as MGM head Louis B. Mayer sweetened the deal for a reluctant Clark Gable by giving him enough money to settle a divorce agreement with Langham and marry Lombard. Gable divorced Langham on March 7, 1939 and proposed to Lombard in a telephone booth at the Brown Derby.

During a break in production on Gone With the Wind, Gable and Lombard drove out to Kingman, Arizona on March 29, 1939 and were married in a quiet ceremony with only Gable's press agent, Otto Winkler, in attendance. They bought a ranch previously owned by director Raoul Walsh in Encino, California and lived a happy, unpretentious life, calling each other "Ma" and "Pa" and raising chickens and horses. Although they attempted, their efforts to have a child were ultimately unsuccessful.

Off-screen, Lombard was much loved for her unpretentious personality and well known for her earthy sense of humor and blue language. Friends of Lombard's included Alfred Hitchcock, Marion Davies, William Haines, Jean Harlow, Fred MacMurray, Cary Grant, Jack Benny, Jorge Negrete, William Powell, and Lucille Ball.

(1937).]]

Shortly after her death at the age of 33, Gable (who was inconsolable and devastated by her loss) joined the United States Army Air Forces. After officers training, Gable headed a six-man motion picture unit attached to a B-17 bomb group in England to film aerial gunners in combat, flying five missions himself. Gable attended the launch of the Liberty ship , named in her honor, on January 15, 1944.

On January 18, 1942, Jack Benny did not perform his usual program, both out of respect for Lombard and grief at her death. Instead, he devoted his program to an all-music format.

Lombard's final film, To Be or Not to Be (1942), directed by Ernst Lubitsch and co-starring Jack Benny, a satire about Nazism and World War II, was in post-production at the time of her death. The film's producers decided to cut the part of the film in which her character asks, "What can happen on a plane?" as they felt it was in poor taste, given the circumstances of Lombard's death.

At the time of her death, Lombard had been scheduled to star in the film They All Kissed the Bride; when production started, her role was given to Joan Crawford. Crawford donated all of her pay for this film to the Red Cross.

Lombard is interred at the Forest Lawn Memorial Park Cemetery in Glendale, California. The name on her crypt marker is "Carole Lombard Gable". Although Gable remarried, he was interred next to her when he died in 1960. Bess Peters was also interred beside her daughter .

Lombard's Fort Wayne childhood home has been designated a historic landmark. The city named the nearby bridge over the St Mary's River the "Carole Lombard Memorial Bridge." (1937)]]

Category:20th-century actors Category:Accidental deaths in Nevada Category:Actors from Indiana Category:American Bahá'ís Category:American film actors Category:American silent film actors Category:Burials at Forest Lawn Memorial Park (Glendale) Category:California Democrats Category:Fairfax High School (Los Angeles) alumni Category:American actors of German descent Category:American actors of English descent Category:Indiana Democrats Category:People from Fort Wayne, Indiana Category:Victims of aviation accidents or incidents in the United States Category:1908 births Category:1942 deaths

This text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.