Professor of English, Mansfield University

Several years ago I taught The Blonde on the Street Corner to a summer school class of undergraduates.. One of the students stated that she understood perfectly Ralph Creel’s frustration at not being able to break free of whatever prevented him from escaping the street corner, his dippy friends, and his parents. He was on a permanent merry-go-round, never able to grab the brass ring. She especially understood those long walks in the park. She understood because, she confessed, she was both a creative person and a manic depressive, and thought Ralph was. It is this kind of ability to embody in stories what readers understand at a most personal level that makes Goodis a fine writer. For some, it’s his description of working class men; for others the look, feel, and smells of the kind of city in which they grew up; for still others it’s his protagonists’ letting go of pent-up frustrations in a whirlwind of feral violence.

Goodis seemed to have found a way of universalizing what may have well been a personal existential situation. In doing so, he generalizes his neuroses into obsessions rooted in 20th century urban life. Manic depression is one of these, and so is restoration, if not regeneration, through violence. Those epic street fights, extensions of the writers’ interest in prize fighting, still thrill his readers. Another kind of objectifying is Goodis’ unique treatment of self-hatred. That is a subject on which much has been written, particularly from the point of view of ethnic (especially Jewish) minorities. Stereotypes about one’s physical weakness, vulgarity, or sexual dysfunction get deep under one’s skin. Goodis, unlike writers such as Philip Roth, Samuel Ornitz, Michael Gold, Woody Allen, or Bernard Malamud, does not write about Jewish people and their experiences. Self-hatred, however, is a chronic disability in both his minor and major characters: Kerrigan, and also his clownish drinking buddy Mooney, and Newton Channing, the slumming alcoholic in The Moon in the Gutter; Chet in Street of the Lost; James Bevan in The Wounded and the Slain; Ralph in The Blonde on the Street Corner.

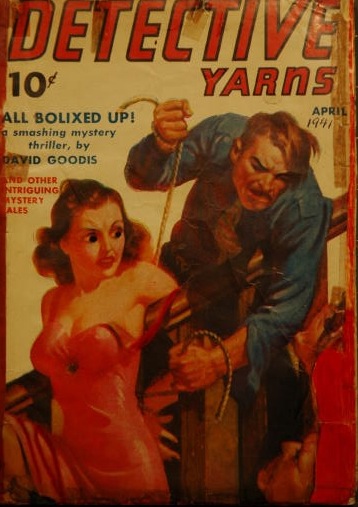

Jay A. Gertzman

Typical of noir crime novels is inevitability and stoicism. The most striking heroes (and that is the way I think of them), Black Friday’s Hart, Street of No Return’s Whitey, and Piano Player’s Eddie, seem to eat and breathe not embittered resignation but rather the grace under pressure that is so important to Hemingway’s protagonists (who also have psychic wounds under which to bear up). They, like Goodis’, are no less fascinating because they are pessimistic, or because they have left behind forever the kind of American Dream that empowers consumerism, uses “decency” as a shibboleth, and sanctifies security. Other writers whose best insights echo in Goodis’ pages include Kafka (don’t even try to escape) and Berthold Brecht (“There’s only two kinds of people in this world, the ones who get kicked around and those who do the kicking,” straight out of The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny but recalled in “Black Pudding” by an ex-con hiding in a tenement in Philly’s Skid Row). A lot more about David Goodis, including his literary and editorial influences, needs to be discovered before we can give him his due as the substantial American writer he is. For example, film maker Larry Withers has uncovered his amazing travel itinerary.

Among writers describing Philadelphia , Goodis is the one that makes me imagine he is with his characters as he describes their lives. He must have been there alongside them: the hobo hotels of Vine Street; the bars, hash houses, and residences of Port Richmond or Southwark; a wind- and rain- flooded Delaware Avenue, the bizarre congestion of machines, aromas, men and trucks at the pre-dawn Dock Street market. Goodis passionately puts his readers into the picture, making the setting a living extension of his characters’ anger, brutality, hard-bitten community spirit, and stoic nobility.

This essay appeared in the GoodisCON program book.

David Goodis' Hardboiled Philadelphia by Jay A. Gertzman .