David Goodis' literary life

out in the cold

By Anthony Neil Smith

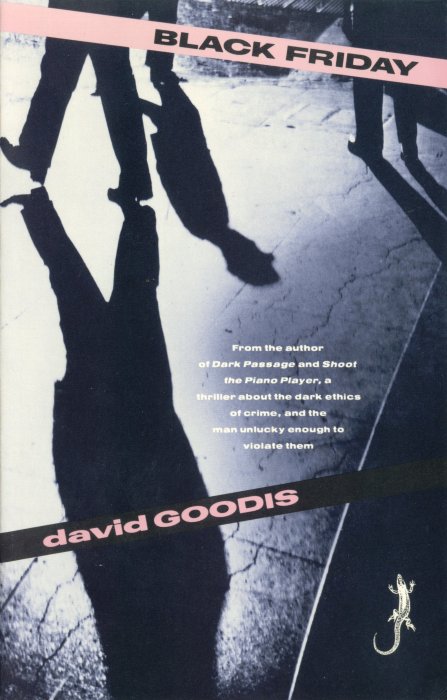

“January Cold came in from two rivers, formed four walls around Hart and closed in on him.” --Black Friday

What did it take for noir novelist David Goodis to get the type of literary attention he deserved?

The goddamned French.

Actually, the goddamned French New Wave. (Well, to be fair, the French had admired David Goodis as a literary artist already by then, but just play along.)

Wet behind the ears director Francois Truffaut plucked Down There from the newsstand and turned it into Shoot the Piano Player, a seminal film, a new direction in cinema, a more playful and inventive style that aimed for realism over glamour, and using American pulp as its sandbox. And while Truffaut kept the basic storyline (he moved the location from Philadelphia to France, of course) and the stream-of-consciousness internal monologues that helped Goodis stand out from his peers, he changed enough of the details and elements that the critics give him most of the credit for classing up a cheap pulp novel, rather than admitting that the work of Goodis was always several steps ahead of the other Gold Medal paperback writers, the work good enough to stand up beside the book that had earned him literary fame in the mid-Forties—Dark Passage.

So why is it that in spite of such a strong note of support from a now legendary director, along with the obviously well-deserved attention of his best known works, David Goodis remains a cult writer amongst the literati?

By the time Goodis escaped his failed screenwriting career and returned home to Philadelphia to settle down, the type of noir work he’d been applauded for in the Forties had been relegated to the paperback racks. Cheap, disposable, just like those pulps Goodis had slaved over in the thirties under many different names and many different themes, purely for money and the experience. He’d climbed out of the pulp pool, publishing a solid literary novel before hitting it big with Dark Passage. After trying to build on that success in the movies, but not getting very far at all, his return to novels meant a return to the mean streets, noir dark as midnight.

Today’s critics can’t help but temper their praise of Goodis with a little “not bad…for pulp” attitude. In a review of The Blonde on the Street Corner on Salon.com, David Ulin admits that Goodis “is a lost master of hard-boiled fiction, a writer who has never received his due,” before going on to say about the book, “Ultimately, there's nothing remarkable about this, except for the acuity with which Goodis traces the trajectory of broken dreams.” It seems an odd backhanded compliment, almost an oxymoron.

But maybe that’s spot-on. Goodis could’ve been a giant, one whose novels might somehow have been accepted beyond the cult readers, beyond the newsstand readers, beyond those looking simply for an entertaining way to pass a few hours. He could be in the canon with Hammett and Chandler , or at least enjoy the popular resurgence of the less talented (but still grand) Jim Thompson, another pulp toiler who never seemed to climb out of whatever rut he’d dug for himself. What would it have taken for Goodis to “receive his due”?

Perhaps we should start by looking at the package itself--the paperback original. It’s never gotten the appreciation it deserves. Scottish crime writer Allan Guthrie tells me, “There aren't any writers of mid-20th century paperback original crime novels who are given credit as great writers…Then Goodis' books weren't reprinted for decades. And when they were reprinted, it was by small presses. As a result, most literary critics have never heard of Goodis.” One wonders if Goodis and the other paperback writers knew that they were risking literary oblivion when they signed on for this “experiment” in publishing. Economically, it felt right. Readers ate the shit up, sending sales skyrocketing for writers like Goodis, Spillane, McBain, and Hamilton. The novels were short, cheap, and everywhere. Well, everywhere except the reviewer’s desk. Almost like class warfare--it didn’t matter how good the final product was if the messenger wore a cheap suit and used rough slang.

To be fair, some writers still managed to achieve literary success after a run of pulp novels. Just check out a list of Gold Medal alums and you’ll find Kurt Vonnegut, Elmore Leonard, John D. Macdonald, along with several other surprises. Goodis is also on that list, and nearly everyone agrees his novels are head and shoulders above almost all the pulp writers slaving away back then. So his being passed over for so many years could be connected to the fact that it’s hard to remember a novel that’s printed on cheap paper and designed to fall apart. No one meditated on the striking craftsmanship and depth of the Goodis they had just read. They just wanted the next one. And the next. All forgotten by the time television had entrenched itself as an easier way to kill time than books.

Or could it be that he was too ahead of his time? That what we now consider to be pretty tame on the scale of lewd entertainment could’ve been marginalized as slightly-above-pornography at the time? In his review of Black Friday at Bookmuch, Chris Pickering writes“…the extreme violence described isn’t even remotely as shocking as I was led to believe. Though the description of the disposal of a dead body can conjure up many an unwanted image, there’s little to fulfill the bloodlust of today’s Tarantino obsessed readers.” Ahead of its time then, but now it’s not up to speed with our own pulp culture? I can’t agree. It still packs a punch, mainly because Goodis doesn’t concentrate on the gore or the violence so much as he does Hart’s reaction to it, and its later consequences. Seems like the literary engine at the heart of the novel is working just fine, thank you.

It could also be said that maybe Goodis’ obsessions kept him from expanding his subject matter, thus forever writing the same book--an artist/writer/musician who aims for the stars but comes up short, then somehow ends up tangled in crime. There’s always a blonde, there’s always a brother, and nobody ever leaves happy. We are reminded of the moment in Black Friday when Hart evaluates Rizzio’s paintings, telling him they’re very good. Rizzio reacts like he hadn’t heard that before, none of his gang ever giving him credit for his talent. In fact Charley, the head guy, becomes suspicious of Hart after that before figuring a way to use his painting smarts to help them in the robbery. We think of the moment in Down There when Lena reveals to Eddie that she knows more about his past as a famous concert pianist than she had let on, and how that triggers some bad memories for our melancholy hero.

Has Goodis really led us in psychoanalytical circles? Do all of the artists and all of the brothers and all the women really point his failure to live up to the success of Dark Passage, having to deal with his brother’s schizophrenia, and his own internal struggle in dealing with the opposite sex? If so, that shouldn’t be counted against him as a literary icon. Wasn’t Hemingway himself obsessed with sports and women? Fitzgerald with bored rich folks? Steinbeck with class warfare? Many classic writers have recycled their obsessions endlessly, always chipping away at their souls one novel at a time. In noir, James Ellroy is consumed with his mother’s murder. George Pelecanos writes mostly about the hard knock life on the streets of Washington D.C. Rather than marginalize Goodis’ work because of the similarities in his novels, we should celebrate the dark core around which his fiction swirled, always revisiting the same themes, ever so close to refining them into the Great American Novel…but not quite getting there.

Then again, maybe it’s just the darkness itself keeping readers away. The same could be said of many noir writers, working in a commercial genre while writing work that the mass audiences don’t find so appealing. They want justice, not despair. A satisfying ending instead of heartbreak. Noir novelist Vicki Hendricks thinks that may be a burden Goodis had to shoulder, as well as successive generations if writers who slink around in the darkness: “The worlds we create are narrow in scope and appeal only to certain strange people, like the writers themselves. The die-hards who love Goodis are those who find beauty in the darkness and ambiguity of life, but that taste is not easily shared with most readers who want to escape just such feelings. Also, possibly Goodis-type readers are generally the loners who don't tend to proselytize, preferring to keep their ‘guilty pleasures’ secret.” So we’re masochists, aren’t we? We bemoan Goodis’ lack of recognition and hope that his reputation will one day creep up until he’s on par with the masters, exactly as he should be. But we’re afraid to share him with the world, thinking the literati might suck away all that we find special about him if given the chance, somehow stealing the secret mojo only the chosen few know currently enjoy. That’s the problem with cults, isn’t it?

Since we’ve already got all of the Goodis books we’ll ever have, there’s no danger in pushing him out into the sunlight. The novels are good, each new reissue not only standing up well next to the noir writers of today, but surpassing them with Goodis’ instincts on human nature--where our society was headed, and how some people just can’t seem to shake their self-destructive tendencies even in the face of certain doom. If we want the novels of Goodis to survive, let’s start making the point that he was a prophet, one of the Old Testament variety. It’s all going to end bad, bad, bad. But Goddamn it, if things have to end in horror, make that horror as vivid and sublime as you can.

This essay appeared in the GoodisCON program book.

Anthony Neil Smith is the author of PSYCHOSOMATIC and THE DRUMMER. He was also editor and co-founder of the late great internet crime zine PLOTS WITH GUNS. Over thirty of his stories, and a handful of essays, have been published in the last six years, two of them receiving honorable mentions from the editors of BEST AMERICAN MYSTERY STORIES. He is currently an Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at Southwest Minnesota State University.

.