For some reason, the email WordPress sent out about my latest radio show posting was blank. Let’s see if this one is too.

You can see the post at https://lbo-news.com/2020/08/13/fresh-audio-product-230/.

For some reason, the email WordPress sent out about my latest radio show posting was blank. Let’s see if this one is too.

You can see the post at https://lbo-news.com/2020/08/13/fresh-audio-product-230/.

Posted in Uncategorized

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

August 13, 2020 Elizabeth Wrigley-Field on race and mortality: years lost to police violence and how many white people would have to die of COVID-19 to equal a “normal” year of black death? (paper here, NYT article here) • Tom Philpott, author of Perilous Bounty, on the ecological crises facing US agriculture

Posted in radio | Tags: agriculture, ecological crisis, farming, Green New Deal, police violence, public health, race disparities

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

August 6, 2020 Edwin Ackerman on Mexican president AMLO • Marcia Chatelain, author of Franchise, on the impact and role of black McDonald’s franchisees

Posted in radio | Tags: AMLO, black politics, franchising, McDonalds, Mexico

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

July 30, 2020 Tobita Chow on the roots and dangers of Sinophobia in the US • Donna Murch, author of Living for the City, on the emergence of the Black Panther Party out of early 1960s campus study groups

Posted in radio | Tags: China, black politics, campus politics, Sinophobia, Black Panther Party

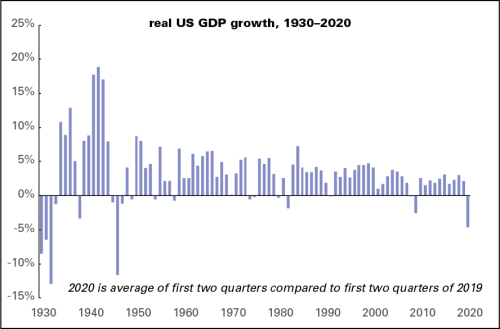

Even non-connoisseurs are reeling from the miserable second quarter GDP numbers released this morning. Between the first and second quarters of this year, GDP was off 33% after adjustment for inflation. That’s by far the biggest decline since quarterly numbers begin in 1947.

That 33% figure is at an annualized rate, meaning GDP would be off by a third if it declined at the second-quarter rate for a full year. The US is unusual in annualizing the data; most other countries report the quarter-to-quarter change without annualizing it. If we did that, it would have been off a mere 9.5%. But no matter how you slice it, it’s awful: more than three times as bad as the previous record, the first quarter of 1958 (a recession that helped elect JFK), and four times as bad as the worst quarter of the 2008–2009 recession, the fourth of 2008.

If you average the first two quarters of this year and compare them to the first two of last year, as the graph below does, you get by far the worst number since 1946, when the US was demobilizing after World War II. Aside from that, you’d have to go back to the Great Depression for bigger negative numbers.

As I’ve pointed out elsewhere, we never really recovered from the 2008 recession. Quoting that to save some keystrokes:

Had the economy continued to grow in line with its 1970–2007 trend, GDP would be about 20% higher than it is now. GDP is a deeply flawed measure; it says little about distribution or quality of life, but it is what the capitalist system runs on. Listen to any pundit or propagandist, and growth is what the whole set-up is all about. And by this most conventional of measures, American capitalism is failing badly on its own terms.

But that 20% shortfall was based on first quarter numbers; the second quarter took it close to 30%, as the graph below shows.

A near-30% shortfall works out to just over $18,000 per person. That’s an aggregate number; it doesn’t mean that we’d each be $18,000 richer had growth held to the old trend. There are things in GDP like investment and government spending that don’t translate into personal income—and since the rich have hogged most GDP growth over the last several decades, the average person would see little of that $18,000. But it is a measure of how much poorer we are as a society because of the economic troubles of the last decade.

Of the 33% annualized decline in GDP, 25 points came from personal consumption, three times the previous worst quarter (the fourth of 1950). That decline in spending came despite the huge boost to personal income provided by the $1,200 stimulus checks and expanded unemployment benefits; it looks like those who could saved their money out of fear it would soon be in very short supply. As the graph below shows, spending on recreation led the way down, off 94%; close behind were transportation, off 84%, and food services and accommodation, off 81%. Spending on clothing & footwear and gasoline & energy were also down hard. Amazingly, spending on health care was down 63%, as people postponed routine care out of fear of catching the virus.

The third quarter is unlikely to be this dire. According to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s GDP tracker, the third quarter is likely to see a sharp rebound—though that’s based largely on early July data. Things look to have slowed as the month progressed—and with the $600 supplemental unemployment benefits gone, at least for now, we could just flatline for a few months. Even if we see some recovery, the long-term damage—people disemployed, businesses shuttered, confidence hammered—will be substantial and lingering.

What a terrible time to be governed by callous morons.

Posted in statistics, Uncategorized | Tags: $18000 shortfall, consumption, depression

[This is the edited text of a talk I gave via Zoom, like everything else these days, sponsored by the North Brooklyn chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America. It reprises and updates several things I’ve written recently, but it’s hard to be original these days. Video will be posted, but who wants to look at me? The Q&A was quite good though.]

Before I get into the body of my talk, I want to celebrate our electoral victories and say how proud I am to be a member of DSA. If you’re not a member, please join. As someone who was a socialist throughout the dark days of the 80s, 90s, and 00s, let me say how great it is to see socialists in Congress and legislative bodies around the country, not to mention vast uprisings across the country. Onward to state power and social transformation!

Long ago I was a right-winger, fervently but briefly, and the title of this little talk, “Reflections on the current disorder,” was one that the dreadful old reactionary William F. Buckley used as his all-purpose evergreen when he was asked what he was going to talk about. Just a tasteless joke, sorry.

This is not your typical recession. Back in the old days, meaning three or four decades after the end of WW2, there was a textbook pattern to the business cycle. After a few years, an expansion would mature, the stock market would get exuberant and frothy, labor markets would tighten (meaning wages would start to rise more rapidly than the employing and owning class liked, because tight labor markets increase workers’ power), inflation would pick up, and the Federal Reserve would raise interest rates to provoke a recession. Stocks would decline, the overall pace of business would slow, unemployment would rise, and wage and price pressures would ebb. The employing and owning class would then feel better about the balance of forces, the Federal Reserve would lower interest rates, and recession would turn into recovery and expansion.

All that began to change with the onset of the neoliberal era forty years ago. The deep recession of the early 1980s crushed labor and led to a massive onslaught on unions and deep cuts in social spending. Wall Street went wild with takeovers and restructurings that led to job cuts, wage cuts, and speedup. The capitalist class, firmly in the driver’s seat, demanded higher profits and higher stock prices above all other priorities.

This has undoubtedly been a great time to be rich. But things haven’t been so great for everyone else. And the whole system got more unstable. Instead of the neat boom and bust cycle I described earlier, we had insane bubbles, reckless speculative manias that would end in crashes. The first was as the leveraging mania 1980s turned into the 1990s; the second, as the dot.com mania of the 1990s turned into the 2000s, and the third as the housing mania of the early 2000s ended in the 2008 crash. Each recovery from those crashes got weaker and weirder, with the very upper brackets making out like bandits and much of the rest of the population feeling like the previous recession had never ended.

The point of this compressed history is that the US economy was getting sicker for a long time. Neoliberalism, by which I mean the belief that markets should be insulated from any political influence and capitalists should be free to do as they please with little restriction, had seriously undermined the system’s integrity. (When I say insulation from political influence I mean of the humane sort. Intervention to make the rich richer, or bail them out when they hit a wall, was perfectly ok—encouraged in fact.) The competence of the state, military and police functions aside, were consciously eroded. Public investment was squeezed, and our physical and social infrastructure left to rot. Class and racial disparities in health widened along with income inequality and economic precarity. Debt levels kept rising, and the cult of maximizing stock prices meant corporations didn’t invest or hire. Many borrowed money just to buy their own stock to raise its price, leaving them in weak financial shape when this crisis hit.

This economic crisis is different from both sorts I’ve been describing. It’s not the garden-variety recession of the post-World War II decades, nor is it like the financial crises of the neoliberal era. It’s the result of mass illness disrupting normal economic life, making it impossible for people to work (though of course many were forced to at great peril) or shop or do all the things that keep the wheels of consumption and production spinning.

But this crisis hit a system that had been structurally weakened because of the systemic rot—the erosion of state capacity, declining health among a lot of the population, increasing financial fragility, inequality, precarity, and the rest. Fragility and precarity are widespread even in what are nominally “good” times.

According to an annual survey of economic well-being by the Federal Reserve—an institution that ironically shows more interest in the topic than most others in US society— done last October, when the unemployment rate was under 4%:

• 16% of adults were unable to pay their monthly bills in full, and another 12% said they couldn’t pay if they were hit with an unexpected $400 expense

• Over a third couldn’t meet an unexpected $400 expense either out of savings or using a credit card they’d pay off at the end of the month. The rest would either carry a credit card balance or throw up their hands in despair.

• One in four skipped medical or dental care because they couldn’t pay

• Almost one in five had unpaid medical debt.

These are averages. It will not surprise you to learn that white people did better than average, and black and Latino people did worse. For example, almost four in five white people were doing ok or living comfortably, compared with about two in three black and Latino people. You could turn that around, though: even in a relatively good year, one in five white people were barely getting by. Almost four in five straight people (yes, I was surprised the Fed asked this question) were doing at least ok, compared with two in three identifying as lesbian, gay, or bisexual.

So that was the situation going into this hellscape. In June, the official unemployment rate was over 11%, three times what it was when the Fed took that survey last year. Unemployment had come down from a peak of almost 15% in April, as people were recalled to work, but that 11% is higher than any month between May 1941 and April of this year. It never got that high during the deep recessions of 1982 and 2008–2009. Under this definition of unemployment, you have to have looked for work in the previous month. If you broaden the definition to include people who’ve given up the job search as hopeless and those who are working part-time but want full-time, it was 18%. Though down from April’s peak, it’s still higher than at any point during the Great Recession of a decade ago.

And it looks like the late spring recovery has run out of steam. Well over a million people a week are still applying for unemployment insurance, and over 30 million are collecting benefits. Not quite half those beneficiaries are on the rolls because of expansion of eligibility to freelancers and other who would not have been eligible under traditional programs.

That expansion of unemployment insurance eligibility was part of the first pandemic relief package, the so-called CARES Act. The CARES Act also included a $600 weekly benefit on top of the normal state benefits. Benefits vary widely by state, ranging from $550 a week in Massachusetts to $215 in Mississippi. (Most southern states pay well under $300.) The national average pre-supplement was $342. So that $600 supplement made a huge difference to millions of people. It has now expired.

As I wrote last week in Jacobin, the unemployment insurance provisions of the CARES Act were the most generous welfare state measures in our ungenerous history. Job losses from late March onward resulted in steep declines in wage and salary income—almost twice as bad as the declines after the 2008 financial crisis and exceeded only by the onset of the Great Depression in the early 1930s. But those declines were more than offset by the huge increases in unemployment insurance benefits, along with the $1,200 checks. These payments were so large that personal income actually rose overall despite the giant hit to wage and salary income.

Personal consumption spending collapsed in late March and early April but stabilized almost the very day the CARES Act passed and began rising when the payments started flowing. According to near-real-time tracking of debit and credit card spending compiled by the Opportunity Insights project, led by the extremely energetic economist Raj Chetty, spending nearly recovered to pre-crisis levels by mid-June. (The graph below is updated from the one in Jacobin. Opportunity Insights is now reporting weekly, not daily, data.) Since then, they’ve begun to slip—and now that the $600 emergency payments have stopped, we can expect them to fall sharply.

These numbers are, of course, aggregates. Lots of people almost certainly haven’t been so lucky. Many reported huge difficulties in filing for unemployment insurance because our systems are so antiquated. Bloomberg—the news service, not the billionaire ex-mayor—was out with a story earlier today that estimated that as much as a quarter of benefits went unpaid because of bottlenecks.

Despite the payments, food banks have been doing record business. According to a new experimental weekly survey from the Census Bureau, there’s been a decline of over 30 million people in the number reporting that they’re getting enough of the food they want. Most, 25 million, say they’re getting enough food, just not what they want, and the rest, almost 5 million, don’t have enough to eat at least some of the time.

Still, there’s no question the supplemental benefits helped a lot. But no longer.

There will probably be a second covid relief bill, but the two parties are far apart on details and the Republicans are divided among themselves. Dems are looking for a $4 trillion package; Republicans, a quarter that. The GOP is leaning towards another round of $1,200 checks, $200 in supplemental unemployment benefits and a cap at 70% of previous wages (something many states say would take them weeks to calculate), job retention tax credits, and liability shields to protect employers against suits from employees forced back to work. They’re also trying to slip the Pentagon almost $4 billion to replace money shifted from its normal budget to build Trump’s border wall. Trump himself wants almost $2 billion to fund a new FBI building on its current site, rather than one out in the suburbs as had previously planned. The reasons for Trump’s concerns, which he expressed right on taking office, are not fully clear, but may involve assuring that nothing could be built on the current site that would compete with his hotel down the block. The Dems want aid for busted state and local governments and school districts; Republicans don’t. The bickering is likely to drag well into August, which means lots of seriously broke people for weeks on end.

And why do the Republicans want to put a tight lid on unemployment benefits? Because, as Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin said, “We’re going to make sure that we don’t pay people more money to stay home than go to work.”

That attitude isn’t stopping Mnuchin for looking to forgive loans extended to businesses under the Paycheck Protection Program, or PPP. Businesses who took the loans were supposed to keep employees on payroll; if they did, the loans would be forgiven. It’s not clear how many did keep employees on the payroll, or how many gamed the system by laying off and then recalling workers before the deadline, but Mnuchin wants to forgive the loans without knowing auditing what happened.

That whole program was a disaster. Much of the money went to areas least affected by either the virus or unemployment. It was administered through banks rather than public authorities, and their decisions were often opaque, arbitrary, and slow. ProPublica reportedthat temp firms got PPP money to “retain” employees that they were renting out to their clients, meaning they got paid twice for the same work. The contrast with European job preservation schemes is striking. They paid employers promptly to keep workers on the job and they did. European unemployment rates have risen only slightly, and their economies look mostly to be recovering. Ours is a wreck.

The recovery in employment is also running out of steam. That same weekly Census Bureau survey reports a 5% decline in employment between mid-June and mid-July, almost 7 million people in numerical terms. As spending slips because the expanded unemployment benefits have expired, it’s hard to see how those employment numbers could do anything but decline further. Add to that the increasing covid toll in the South and West and we have a serious problem on our hands.

How long could this recession last? A long time, I’d say. Not only is a recovery dependent on getting the virus numbers seriously down, there’s a lot of damage to the real economy. As I said at the beginning, this is not merely not a conventional old textbook recession, a story of what the mainstream calls overheating followed by an imposed cooling followed by a normal recovery nor a financial crisis recession, where recovery is inhibited by a huge debt overhang. It’s one caused by immense damage to the real sector—supply chains broken, workers kept off the job by sickness and death (and the fear of sickness and death), firms bankrupted by months of closure who may never reopen and rehire. The Fed can pump money into the markets and the federal government can deficit spend on a previously unimaginable scale, but these problems will take time to heal.

And we haven’t really recovered from the 2008 crisis either. That led to serious long-term economic damage. Had the economy continued to grow in line with its 1970–2007 trend, GDP would be about 20% higher than it is now. GDP is a deeply flawed measure; it says little about distribution or quality of life, but it is what the capitalist system runs on. Listen to any pundit or propagandist, and growth is what the whole set-up is all about. And by this most conventional of measures, American capitalism is failing badly on its own terms.

With all this gloom, why has the stock market been doing so well? I see at least four reasons.

One, the financial markets’ reputation for rationality is thoroughly unearned. The markets are populated by traders with the emotional volatility of fourteen-year-old boys. (Actually, I have a fourteen-year-old son and he’s far more stable than a stock trader.)

Second, the markets have been convinced the virus is going to go away and everything will be better very soon. That bounceback was supposed to begin in the second half of the year; we’re a month into the second half of the year and it’s not here yet. (A major reason to worry: Trump economic advisor Larry Kudlow, who is almost always wrong about everything, says we’re going to see 20% GDP growth in the third and fourth quarters of this year. The US has never seen 20% growth over two quarters since the end of World War II; the closest we came was not quite 15% during the Korean War buildup of 1950. I’m tempted to put a negative sign in front of whatever Kudlow predicts.)

Third, the Federal Reserve has been pumping trillions into the markets for months; that’s potent fuel for a speculative fire.

And fourth, most of the market’s gains are concentrated in five big tech stocks, Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, and Google. They’re up 35% since the beginning of 2020; the rest of the market, as measured by the S&P 500 index, is down 5%. (See graph below, lifted from that Financial Times article.) A 5% decline is not big, given the damage to the real economy, but it tells a much different story from the tech biggies.

So, to ask Lenin’s classic question, what is to be done? Most urgently, people need serious income support, at least $2,000 a month for at least six months. We need eviction and foreclosure moratoriums to prevent what looks like an inevitable wave of mass homelessness as people find it impossible to pay their rent and mortgages. State and local governments and school systems need big support; if they don’t get it there will be massive job and service cuts that will generate misery and deeper depression. Schools can’t reopen safely without a major infusion of resources.

Longer term never has the Green New Deal seemed so practical, Nancy Pelosi’s “green dream or whatever” to the contrary. It has everything we need: the massive public investment program to repair our rotting infrastructure, and the kinds of social spending we need to make the poor not poor and the working and middle classes comfortable and secure.

For decades, civilian public investment net of depreciation has hovered just above 0, meaning that we’re doing little better to replacing things as they decay. (See graph below.) This economic statistic can easily be confirmed just by walking around anywhere in the US outside our richest neighborhoods. We need massive investment in public infrastructure on the model of the New Deal, both to fight the slump and to make this country habitable for the bottom 80–90% of the population. That infrastructure investment must not simply be more of the same—not airports and highways but clean energy and high-speed rail. The investment program needs to be part of a conversion of an economy based on exploitation of workers and nature into something humane and sustainable. The New Deal also subsidized artists and writers, and the projects it created were often beautiful—not driven by the mean, philistine view of life that we usually associate with the public sector.

As an example of the new kind of investment we need, we could put now-unemployed auto workers back to work building vehicles that don’t threaten life on earth. A model to think about was the (sadly unsuccessful) proposal to transform a plant in Ontario GM closed into something earth- and worker-friendly.

We also need to think about industries we don’t want to see recover. The airline industry is in dire shape. It’s also ecologically destructive and we need to imagine a world in which we all continue to fly much less. The cruise industry is filthy and wrecks the towns where those giant ships dock, and it should be euthanized. This would be a propitious time to nationalize the oil and gas sector, undertaken with the idea of putting them out of business. We must move as quickly as possible to stop the use of fossil fuels, and as long as these entities exist, the political and economic obstacles to that necessity are nearly impossible to overcome. Big Oil could be Because the price of oil has fallen so dramatically, the value of the major carbon producers has cratered. The five biggest US-based oil companies (Exxon Mobil, Chevron, ConocoPhillips, Phillips 66, and Valero) have a combined market capitalization of about $400 billion, which is equal to about an eighth of JPMorgan Chase’s total assets and less than 2% of GDP. Shareholders will whine, but as the financial world wakes up to the inevitability of carbon’s obsolescence, the value of their investments will tend towards 0 anyway. In all cases, workers should be protected, not displaced, but the underlying businesses should be wound down or severely shrunk.

The banking system is in decent shape now, surprisingly perhaps, but should the recession continue, as I think it will, this will change as more people and businesses find themselves unable to service their debts. Nationalize several of the largest banks—and unlike the nationalizations in Sweden in the 1990s and the UK a decade ago, they should not be undertaken with the idea of returning them to private ownership as quickly as possible, after the government eats the losses. They should be run on entirely different principles—something like a financial utility, that provides basic services like checking and savings accounts, but not incomprehensible financial products.

There’s no reason the nationalized banks couldn’t be run to finance the Green New Deal. Some of the GND will have to be financed with traditional tax- and bond-financed public spending, but there’s no reason these socialized banks couldn’t participate.

Along with the nationalized banks, we should create something on the model of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, to finance the GND. It would be a publicly capitalized bank that would evaluate and fund projects like clean energy generation and new models of food production.

At the same time, we should severely rein in with an eye to abolishing, the shadow banking sector of private equity (PE) and hedge funds. PE has saddled companies with crippling levels of debt, which enrich their investors but put them at great risk of failure even in relatively good times. (A subset of PE, venture capital, can play a more constructive economic role, but it’s quite small: there was less than $10 billion in early-stage financing from the sector last year.) Hedge funds do little but destabilize markets and serve no useful purpose.

And never has the need for Medicare for All been so clear. And the reason for that isn’t only the need of freeing people from the anxiety of not being able to pay for essential care, but also because there is little in the way of planning for the distribution of health care resources beyond what The Market demands. A major part of the reason the US is so unprepared to handle the coronavirus crisis is that hospitals are built and outfitted according to where the money is, not where the needs are. Hospitals in both cities and rural areas are broke and closing in the middle of a health emergency. They need to be built where they can serve people who need them.

A lot of this may seem pie in the sky, but who ever thought there’d be a socialist caucus in the New York State legislature? The right still has political power but it’s widely discredited, and mainstream Democrats are out of ideas. We’re deep in a massive economic and social crisis and we’ve got the energy and ideas and they don’t. Now is not the time to be shy!

Posted in talk, Uncategorized | Tags: CARES Act, consumption, COVID-19, crisis, depression, Green New Deal, unemployment

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

July 23, 2020 Jason Wilson on the protests and storm troopers in Portland • Forrest Hylton on COVID-19, repression, corruption, and drug gangs in Latin America

Posted in radio | Tags: Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, COVID-19, drug gangs, homeland security, Portland, protest, storm troopers

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

July 16, 2020 Claire Potter, author of Political Junkies, on how our politics got so divided • Sonia Shah, author of this article, thinks about the pandemic in more than biomedical terms

Posted in radio | Tags: COVID-19, divisiveness, media, politics

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

July 9, 2020 Erin Thompson on art crime and the history of toppling statues • Jennifer Cohen on gendering the health and economic crises [back after another brief vacation break]

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

June 25, 2020 Nikhil Pal Singh on race, class, policing, protest • Michael Kinnucan of Brooklyn DSA’s electoral committee on left victories in the NYC primary elections

Posted in radio, Uncategorized | Tags: class, DSA, electoral politics, identity, New York City, police, protest, race

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

June 18, 2020 Eric Reinhart on jails as COVID-19 spreaders (article here, AER article on pretrial detention here) • Erin Hatton on “coerced” workers, from prisoners to grad students [back after vacation break]

Posted in radio, Uncategorized | Tags: coercion, COVID-19, incarceration, jails, labor, prisoners

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

June 4, 2020 Alex Vitale, author of The End of Policing, on why cops are being so brutal and what should be done with them • Ben Tarnoff, co-founder of Logic magazine, on tech worker organizing (essay here)

Posted in radio | Tags: labor militancy, police, tech workers, unions

As do many other cities, but since I’m a New Yorker, I’m leading with the hometown news.

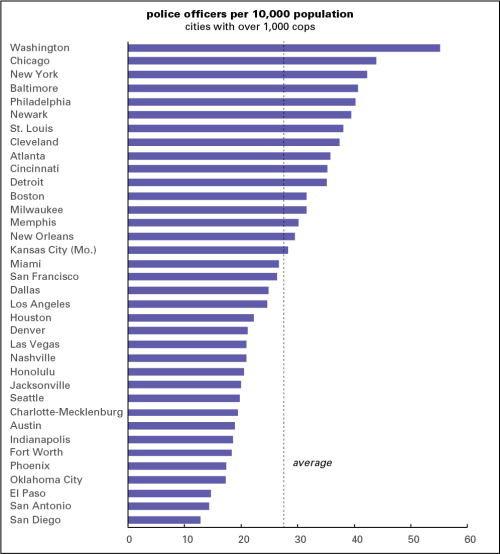

US cities vary widely in the number of cops they have relative to their population, as the graph below (drawn from data assembled by Governing magazine). Among big cities, DC, Chicago, New York, Baltimore, and Philadelphia top the list, with over 40 officers per 10,000 people. These are well above the national average of just under 28 per 10,000. Cities toward the bottom of the list have 20 or fewer.

If New York had an average number of cops, and not one of the highest ratios to population of any city in the country, we’d have 23,645 officers, not 36,228. If we had San Diego’s ratio, we’d have just 11,422, half as many as that average (which falls between Miami and Kansas City).

So, if New York wanted to be just average, we could fire 12,500 cops. If we wanted to be like San Diego, minus the nice weather and the US Navy, we could fire almost 25,000. We don’t have to be harsh about it. We could give them nice new jobs doing useful things instead of beating and shooting people, or a generous severance package if they prefer.

Even 11,422 is probably too many cops. But that’s another conversation.

Posted in observation, Uncategorized | Tags: police

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

May 28, 2020 Excerpts from a virtual panel sponsored by Red May, Seattle: Jodi Dean, Leo Panitch, and Asad Haider on the current crisis, with lots about how socialists should engage with the state (full session, with video, here)

Posted in radio | Tags: coronacrisis, dual power, Marxism, state theory