An antifascist report on the far right movement that embraced Donald Trump.

Click the icon to order Ctrl-Alt-Delete.

This report is excerpted from Matthew N. Lyons’s forthcoming book, Insurgent Supremacists: The U.S. Far Right’s Challenge to State and Empire, to be published by PM Press and Kersplebedeb Publishing. This report is also featured in Ctrl-Alt-Delete: An Antifascist Report on the Alternative Right, which is now available for pre-order.

For a printer-friendly PDF version, click HERE.

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

The Alt Right, short for “Alternative Right,” is a loosely organized far-right movement that emphasizes internet activism, is hostile to both multicultural liberalism and mainstream conservatism, and has had a symbiotic relationship with Donald Trump’s presidential campaign. The Alt Right brings together different branches of White nationalism, including “scientific” racists, sections of the neonazi movement, and adherents of European New Right ideology. The Alt Right also encompasses rightist ideologies that don’t center on race, above all efforts to destroy feminism and re-intensify men’s dominance over women, as well as other elitist and authoritarian currents. The Alt Right has little formal organization but has made effective use of online tactics.

This report offers an overview of the Alt Right’s history, ideology, and relationship with the Trump campaign and presidential administration.

Part 1 – Origins and development

Major forerunners of the Alt Right included paleoconservatism, an anti-interventionist, anti-free trade, anti-immigration branch of U.S. conservatism that emerged in the late 1980s; and the European New Right (ENR), a project that began in France in the late 1960s to rework fascist ideology by appropriating elements of liberal and leftist thought to mask anti-egalitarianism.

The term “Alternative Right” was introduced by Richard Spencer in 2008 and initially was a catch-all encompassing paleoconservatives, libertarians, White nationalists, and other rightists at odds with the conservative establishment. AlternativeRight.com, an online magazine which Spencer founded and edited from 2010 to 2012, became a popular intellectual forum for a range of dissident rightist views, including “scientific” racism, the ENR, National-Anarchism, libertarianism, male tribalism, and Black conservatism. Gradually, the term Alternative Right or Alt Right became more closely tied to White nationalism and the goal of creating a White ethnostate, as a number of other White nationalist publications became associated with the Alt Right and as Spencer focused more sharply on White nationalism after becoming head of the National Policy Institute in 2011.

Starting in 2015, the Alt Right broadened out from a small intellectual circle as a much wider array of online activists embraced the term. Many of these newer Alt Rightists were based in discussion websites such as Reddit, 4chan, and 8chan. Some of them, such as Andrew Anglin of The Daily Stormer, brought neonazi-based politics into the movement.

Part 2 – Major Ideological Currents

Some Alt Rightists have used moderate-sounding intellectual tones, often borrowing from the ENR’s euphemistic language about respecting “difference” and protecting “biocultural diversity.” But many others have used naked bigotry and supremacist speech in an effort to be as inflammatory as possible. This stylistic difference is more division of labor than factional conflict.

Most Alt Rightists regard Jews as dangerous outsiders who bear major responsibility for the decline of European civilization, but they disagree about whether or not to work with them. Neonazi-oriented Alt Rightists reject any association with Jews and regard them as the embodiment of pure evil. Other Alt Rightists, however, advocate a tactical alliance with right-wing Jews against Muslims and immigrants of color, and believe that migration to Israel will help prevent Jews from subverting western societies. A few Alt Rightists have welcomed like-minded Jews to movement publications and events.

The Alt Right has increasingly embraced an intensely misogynistic ideology, which argues that women need and want men to rule over them and should be stripped of any political role. This largely reflects the influence of the manosphere, an online antifeminist subculture of men who falsely claim that men in U.S. society are oppressed by feminism or by women in general. Although there has been some tension between the two movements over racial politics, many manospherians have also become active in the Alt Right, and the manosphere’s online harassment campaigns against women have strongly influenced the Alt Right’s own activism. The Alt Right has also been influenced by the “male tribalism” of Jack Donovan, a longtime Alt Right speaker and writer who advocates a social and political order based on small, close-knit “gangs” of male warriors.

Many Alt Rightists consider homosexuality in any form to be immoral and a threat to racial survival, but there has also been a trend to welcome some homosexual men (such as Jack Donovan) while continuing to derogate gay culture. Alt Rightists uphold classical fascism’s elitist and anti-democratic views of governance, but their goal of breaking up the United States into ethnically separate polities is inherently decentralist. This blend of authoritarianism and decentralism, rooted in the European New Right and paleoconservatism, has been bolstered by two other political currents that overlap with the Alt Right: (a) right-wing anarchists (including National-Anarchists and Keith Preston’s Attack the System website), who want to dismantle the centralized state but uphold non-state systems of hierarchy and oppression; and (b) the neoreactionary movement (also known as the Dark Enlightenment), an offshoot of libertarianism which rejects popular sovereignty and advocates small-scale authoritarian enclaves such as seasteads.

Part 3 – Relationship with Donald Trump

Alt Rightists have long argued about whether to work within existing political channels or reject them entirely. Many Alt Rightists, borrowing from the ENR, have focused on a “metapolitical” strategy of seeking to transform the broader political culture and thereby lay the groundwork for structural change.

A majority of Alt Rightists supported Donald Trump’s presidential candidacy, although they recognized that Trump was not one of them and was not going to bring about the change they wanted. Rather, they believed that Trump’s campaign could weaken the Republican Party and shift political discussion in ways that Alt Rightists could use to promote their own ideology. A minority of Alt Rightists opposed Trump because they believed he was loyal to Israel, promoted illusory faith in the U.S. political system, or would co-opt their movement into supporting established elites.

Alt Rightists helped Trump’s campaign through online activism, including skillful use of online memes such as #Cuckservative and #DraftOurDaughters to discredit Trump’s opponents, as well as coordinated online harassment, which often involved floods of abusive messages and images, rape and death threats, and doxxing (public releases of personal information) targeting individual Trump opponents and members of their families. In return, the Trump campaign gave the Alt Right greater visibility, influence, and sense of purpose.

As the Alt Right grew and attracted attention, some conservatives—who became known as the “Alt Lite”—took on the role of apologists or supporters for the Alt Right, helping to spread a lot of its message without embracing its full ideology or its ethnostate goals. In the public mind, prominent Alt Lite figures such as Milo Yiannopoulos and Steve Bannon of the Breitbart News Network have often been equated with the Alt Right itself. The Alt Right has relied on such figures to help bring its ideas to a mainstream audience, but many Alt Rightists have regarded them as untrustworthy opportunists.

Conclusion – the Alt Right and the Trump presidency

Many Alt Rightists see themselves as the Trump coalition’s political vanguard, taking hardline positions that pull Trump further to the Right while enabling him to look moderate by comparison. However, the question of how to play that vanguard role has sharpened tensions both within the Alt Right and between the Alt Right and its sympathizers.

Because Trump has mostly chosen hardline establishment figures for his administration, Alt Rightists could easily find themselves pushed into an oppositional role. Yet Alt Rightists could continue to exert significant pressure on the Trump administration, because they know how to speak effectively to a large part of his popular base. They are in a strong position to continue influencing the political culture.

Introduction

Maybe you first heard about them in the summer of 2015, when they promoted the insult “cuckservative” to attack Trump’s opponents in the Republican primaries.1 Maybe it was in August 2016, when Hillary Clinton denounced them as “a fringe element” that had “effectively taken over the Republican party.”2 Or maybe it was a couple of weeks after Trump’s surprise defeat of Clinton, when a group of them were caught on camera giving the fascist salute in response to a speaker shouting “Hail Trump, hail our people, hail victory!”3

The Alt Right helped Donald Trump get elected president, and Trump’s campaign put the Alt Right in the news. But the movement was active well before Trump announced his candidacy, and its relationship with Trump has been more complex and more qualified than many critics realize. The Alt Right is just one of multiple dangerous forces associated with Trump, but it’s the one that has attracted the greatest notoriety. However, it’s not accurate to argue, as many critics have, that “Alt Right” is just a deceptive code-phrase meant to hide the movement’s White supremacist or neonazi politics. This is a movement with its own story, and for those concerned about the seemingly sudden resurgence of far-right politics in the United States, it is a story worth exploring.

This logo for the Alt Right has been appearing online, on posters, and at events.

The Alt Right, short for “alternative right,” is a loosely organized far-right movement that shares a contempt for both liberal multiculturalism and mainstream conservatism; a belief that some people are inherently superior to others; a strong internet presence and embrace of specific elements of online culture; and a self-presentation as being new, hip, and irreverent.4 Based primarily in the United States, Alt Right ideology combines White nationalism, misogyny, antisemitism, and authoritarianism in various forms and in political styles ranging from intellectual argument to violent invective. White nationalism constitutes the movement’s center of gravity, but some Alt Rightists are more focused on reasserting male dominance or other forms of elitism rather than race. The Alt Right has little in the way of formal organization, but has used internet memes effectively to gain visibility, rally supporters, and target opponents. Most Alt Rightists have rallied behind Trump’s presidential bid, yet as a rule Alt Rightists regard the existing political system as hopeless and call for replacing the United States with one or more racially defined homelands.

This report offers an overview of the Alt Right’s history, beliefs, and relationship with other political forces. Part 1 traces the movement’s ideological origins in paleoconservatism and the European New Right, and its development since Richard Spencer launched the original AlternativeRight.com website in 2010. Part 2 surveys the major political currents that comprise or overlap with the Alt Right, which include in their ranks White nationalists, members of the antifeminist “manosphere,” male tribalists, right-wing anarchists, and neoreactionaries. Part 3 focuses on the Alt Right’s relationship with the Trump presidential campaign, including movement debates about political strategy, online political tactics, and its relationship to a network of conservative supporters and popularizers known as the “Alt Lite.” A concluding section offers preliminary thoughts on the Alt Right’s prospects and the potential challenges it will face under the incoming Trump administration.

PART 1 – ORIGINS AND DEVELOPMENT

Ideological roots

Two intellectual currents played key roles in shaping the early Alternative Right: paleoconservatism and the European New Right.

Paleoconservatives can trace their lineage back to the “Old Right” of the 1930s, which opposed New Deal liberalism, and to the America First movement of the early 1940s, which opposed U.S. entry into World War II. To varying degrees, many of the America Firsters were sympathetic to fascism and fascist claims of a sinister Jewish-British conspiracy. In the early 1950s, this current supported Senator Joe McCarthy’s witch-hunting crusade, which extended red-baiting to target representatives of the centrist Eastern Establishment. After McCarthy, the America First/anti-New Deal Right was largely submerged in a broader “fusionist” conservative movement, in which Cold War anticommunism served as the glue holding different rightist currents together. But when the Soviet bloc collapsed between 1989 and 1991, this anticommunist alliance unraveled, and old debates reemerged.5

In the 1980s, devotees of the Old Right began calling themselves paleoconservatives as a reaction against neoconservatives, those often formerly liberal and leftist intellectuals who were then gaining influential positions in right-wing think-tanks and the Reagan administration. The first neocons were predominantly Jewish and Catholic, which put them outside the ranks of old-guard conservatism. Neocons promoted an aggressive foreign policy to spread U.S. “democracy” throughout the world and supported a close alliance with Israel, but they also favored nonrestrictive immigration policies and, to a limited extent, social welfare programs. Paleconservatives regarded the neocons as usurpers and closet leftists, and in the post-Soviet era they criticized military interventionism, free trade, immigration, globalization, and the welfare state. They also spoke out against Washington’s close alliance with Israel, often in terms that had anti-Jewish undertones. Paleoconservatives tended to be unapologetic champions of European Christian culture, and some of them gravitated toward White nationalism, advocating a society in which White people, their values, interests, and concerns would always be explicitly preeminent. To some extent they began to converge with more hardline White supremacists during this period.6

These positions attracted little elite support, and after Reagan paleocons were mostly frozen out of political power. But they attracted significant popular support. In 1992 and 1996, Patrick Buchanan won millions of votes in Republican presidential primaries by emphasizing paleocon themes. Paleocons also played key roles in building the anti-immigrant and neo-Confederate movements in the ‘90s, and influenced the Patriot movement, which exploded briefly in the mid-90s around fears that globalist elites were plotting to impose a tyrannical world government on the United States. Some self-described libertarians, such as former Congressmember Ron Paul, embraced paleoconservative positions on culture and foreign policy.7 After the September 11th attacks in 2001, the resurgence of military interventionism and neoconservatives’ prominent roles in the George W. Bush administration solidified the paleocons’ position as political outsiders.8

The Alt Right’s other significant forerunner, the European New Right (ENR), developed along different lines. The ENR began in France in the late 1960s and then spread to other European countries as an initiative among far-right intellectuals to rework fascist ideology, largely by appropriating elements from other political traditions—including the Left—to mask their fundamental rejection of the principle of human equality.9 European New Rightists championed “biocultural diversity” against the homogenization supposedly brought by liberalism and globalization. They argued that true antiracism requires separating racial and ethnic groups to protect their unique cultures, and that true feminism defends natural gender differences, instead of supposedly forcing women to “divest themselves of their femininity.” ENR writers also rejected the principle of universal human rights as “a strategic weapon of Western ethnocentrism” that stifles cultural diversity.10

European New Rightists dissociated themselves from traditional fascism in various other ways as well. In the wake of France’s defeat by anticolonial forces in Algeria, they advocated anti-imperialism rather than expansionism and a federated “empire” of regionally based, ethnically homogeneous communities, rather than a big, centralized state. Instead of organizing a mass movement to seize state power, they advocated a “metapolitical” strategy that would gradually transform the political and intellectual culture as a precursor to transforming institutions and systems. In place of classical fascism’s familiar leaders and ideologues, European New Rightists championed more obscure far rightist intellectuals of the 1920s, ‘30s, and beyond, such Julius Evola of Italy, Ernst Jünger and Carl Schmitt of Germany, and Corneliu Codreanu of Romania.

ENR ideology began to get attention in the United States in the 1990s,11 resonating with paleoconservatism on various themes, notably opposition to multicultural societies, non-White immigration, and globalization. On other issues, the two movements tended to be at odds: reflecting their roots in classical fascism but in sharp contrast to paleocons, European New Rightists were hostile to liberal individualism and laissez faire capitalism, and many of them rejected Christianity in favor of paganism. Nonetheless, some kind of dialog between paleocon and ENR ideas held promise for Americans seeking to develop a White nationalist movement outside of traditional neonazi/Ku Klux Klan circles.

Early years and growth

Richard Spencer speaking at a National Policy Institute conference in 2016.

The term “Alternative Right” was introduced by Richard Spencer in 2008, when he was managing editor at the paleocon and libertarian Taki’s Magazine. At Taki’s Magazine the phrase was used as a catch-all for a variety of right-wing voices at odds with the conservative establishment, including paleocons, libertarians, and White nationalists.12 Two years later Spencer left to found a new publication, AlternativeRight.com, as “an online magazine of radical traditionalism.” Joining Spencer were two senior contributing editors, Peter Brimelow (whose anti-immigrant VDARE Foundation sponsored the project) and Paul Gottfried (one of paleoconservatism’s founders and one of its few Jews). AlternativeRight.com quickly became a popular forum among dissident rightist intellectuals, especially younger ones. The magazine published works of old-school “scientific” racism along with articles from or about the European New Right, Italian far right philosopher Julius Evola, and figures from Germany’s interwar Conservative Revolutionary movement. There were essays by National-Anarchist Andrew Yeoman, libertarian and Pat Buchanan supporter Justin Raimondo of Antiwar.com, male tribalist Jack Donovan, and Black conservative Elizabeth Wright.13

AlternativeRight.com developed ties with a number of other White nationalist intellectual publications, which eventually became associated with the term Alternative Right. Some of its main partners included VDARE.com; Jared Taylor’s American Renaissance, whose conferences attracted both antisemites and right-wing Jews; The Occidental Quarterly and its online magazine, The Occidental Observer, currently edited by prominent antisemitic intellectual Kevin MacDonald; and Counter-Currents Publishing, which was founded in 2010 to “create an intellectual movement in North America that is analogous to the European New Right” and “lay the intellectual groundwork for a white ethnostate in North America.”14

Founded in 2005, The National Policy Institute is a White nationalist, White supremacist think tank based in Arlington, Virginia.

In 2011, Richard Spencer became head of the White nationalist think-tank National Policy Institute (NPI) and its affiliated Washington Summit Publishers. He turned AlternativeRight.com over to other editors the following year, then shut it down completely, establishing a new online magazine, Radix, in its place. (The other editors then reestablished Alternative Right as a blog.) Compared with AlternativeRight.com’s broad ideological approach, Spencer’s later entities were more sharply focused on promoting White nationalism. Starting in 2011, NPI held a series of high-profile conferences that brought together intellectuals and activists from various branches of the movement. In 2014, the think-tank, together with supporters of Russian ENR theorist Aleksandr Dugin, cosponsored a “pan-European” conference in Budapest, although the Hungarian government deported Spencer and denied Dugin a visa.15

Starting in 2015, a much wider array of writers and online activists embraced the Alt Right moniker. As Anti-Fascist News put it, “the ‘alt right’ now often means an internet focused string of commentators, blogs, Twitter accounts, podcasters, and Reddit trolls, all of which combine scientific racism, romantic nationalism, and deconstructionist neo-fascist ideas to create a white nationalist movement that has almost no backwards connection with neo-Nazis and the KKK.”16 Some online centers of this larger, more amorphous Alt Right included the imageboard websites 4chan and 8chan, various Reddit sub-communities, and The Right Stuff blog and podcasts. Some Alt Right outfits offered neonazi-oriented politics (such as The Daily Stormer and the Traditionalist Youth Network), while others did not (such as Occidental Dissent, The Unz Review, Vox Popoli, and Chateau Heartiste).

Message boards like 4chan have become appropriated as online centers of a more amorphous Alt Right.

On many sites, Alt Right politics were presented in terms intended to be as inflammatory as possible, bucking a decades-old trend among U.S. Far Rightists to tone down their beliefs for mass consumption. Previously, antisemitic propagandist Willis Carto and former Ku Klux Klan leader David Duke had made careers of dressing up fascism as “populism” or “conservatism”; now Alt Rightists confidently derided antifascism in the way 1960s radicals had derided anticommunism: “We might not all be proper fascists,” The Right Stuff columnist Lawrence Murray wrote in 2015, “but we’re all a little fash whether we want to be or not. We’re fashy goys—we think a lot of nasty thoughts that keep leftists up at night during their struggle sessions. Might as well embrace it…”17

The Alt Right’s rapid growth partly reflected trends in internet culture, where anonymity and the lack of face-to-face contact have fostered widespread use of insults, bullying, and supremacist speech. More immediately, it reflected recent political developments, such as a backlash against the Black Lives Matter movement and, above all, Donald Trump’s presidential candidacy. A majority of Alt Rightists supported Trump’s campaign because of his anti-immigrant proposals; defamatory rhetoric against Mexicans, Muslims, women, and others; and his clashes with mainstream conservatives and the Republican Party establishment.

PART 2 – MAJOR IDEOLOGICAL CURRENTS

White nationalists, high- and low-brow

The original AlternativeRight.com magazine helped set the parameters of Alt Right White nationalism. In “Why an Alternative Right is Necessary,” published in 2010 soon after the magazine was launched, columnist Richard Hoste offered a paleocon-style criticism of the War on Terror and mainstream conservatives, coupled with a blunt new emphasis on race:

One would think that the odds of a major terrorist attack happening would depend on how many Muslims are allowed to live in the United States. Reducing Islamic immigration in the name of fighting terror would receive widespread public support, be completely practical in a way installing a puppet regime in Afghanistan wouldn’t, and not lead us to kill or torture anybody…. The idea that nothing must be done to stop the March Of Diversity is so entrenched in the minds of those considered of the Right that they will defend America policing the entire planet, torture, indefinite detentions, and a nation on permanent war footing but won’t mention immigration restriction or racial profiling.

We’ve known for a while through neuroscience and cross-adoption studies—if common sense wasn’t enough—that individuals differ in their inherent capabilities. The races do, too, with whites and Asians on the top and blacks at the bottom. The Alternative Right takes it for granted that equality of opportunity means inequality of results for various classes, races, and the two sexes. Without ignoring the importance of culture, we see Western civilization as a unique product of the European gene pool.18

A few months later, Greg Johnson at Counter-Currents Publishing declared that:

The survival of whites in North America and around the world is threatened by a host of bad ideas and policies: egalitarianism, the denial of biological race and sex differences, feminism, emasculation, racial altruism, ethnomasochism and xenophilia, multiculturalism, liberalism, capitalism, non-white immigration, individualism, consumerism, materialism, hedonism, anti-natalism, etc.

He also warned that White people would not survive unless they “work to reduce Jewish power and influence” and “regain political control over a viable national homeland or homelands.”19

In 2016, following the Alternative Right’s rapid growth, Lawrence Murray in The Right Stuff proposed a summary of the movement’s “big tent” philosophy: inequality of both individuals and populations is “a fact of life”; “races and their national subdivisions exist and compete for resources, land and influence”; White people are being suppressed and “must be allowed to take their own side”; men and women have separate roles and heterosexual monogamy is crucial for racial survival; “the franchise should be limited” because universal democracy “gives power to the worst and shackles the fittest”; and “Jewish elites are opposed to our entire program.”20 Alfred W. Clark in Radix offered a slightly different summary. In his view, Alt Rightists recognize human biodiversity; reject universalism; want to reverse Third World immigration into the West; are skeptical of free trade and free market ideology; oppose mainstream Christianity from a variety of religious viewpoints (traditionalist Christian, neo-pagan, atheist, and agnostic); and often (but not always) support Donald Trump. Unlike Murray, Clark noted that Alt Rightists disagree about the “Jewish question,” but generally agree “that Jews have disproportionately been involved in starting left-wing movements of the last 150 years.”21

Alt Rightists have promoted these ideas in different ways. Some have used moderate-sounding intellectual tones, often borrowed from the European New Right’s euphemistic language about respecting “difference” and protecting “biocultural diversity.” For example, the National Policy Institute has promoted “identitarianism,” a concept that was developed by the French New Right and popularized by the French group Bloc Identitaire. In 2015, Richard Spencer introduced an NPI essay contest for young writers on the theme, “Why I’m An Identitarian”:

Identitarianism… eschews nationalist chauvinism, as well as the meaningless, petty nationalism that is tolerated, even encouraged, by the current world system. That said, Identitarianism is itself not a universal value system, like Leftism, monotheism, and most contemporary versions of ‘conservatism.’ To the contrary, Identitarianism is fundamentally about difference, about culture as an expression of a certain people at a certain time…. Identitarianism acknowledges the incommensurable nature of different peoples and cultures—and thus looks forward to a world of true diversity and multiculturalism.22

Very different versions of Alt Right politics are available elsewhere. The Right Stuff website uses a mocking, ironic tone, with rotating tag lines such as “Your rational world is a circle jerk”; “Non-aggression is the triumph of weakness”; “Democracy is an interracial porno”; “Obedience to lawful authority is the foundation of manly character”; and “Life isn’t fair. Sucks for you, but I don’t care.” An article by “Darth Stirner,” titled “Fascist Libertarianism: For a Better World,” further illustrated this style:

Dear libertarian, take the rose colored glasses of racial egalitarianism off. Look around and see that other races don’t even disguise their hatred of you. Even though you don’t think in terms of race, rest assured that they do. Humanity is composed of a series of racial corporations. They stick together, and if we don’t… Western civilization is doomed.

[…]

Progressives, communists, and degenerates of various stripes will need to be interned—at least during the transition period. Terrorism and guerrilla warfare can be prevented with this measure. In the instance of a coup d’état it would be reasonable to detain every person who might conceivably be an enemy of the right-wing revolution. Rather than starving or torturing them they should be treated well with the highest standard of living reasonably possible. Most of them will simply be held until the war is over and the winner is clear. This is actually much more humane than allowing a hotly contested civil war to occur.23

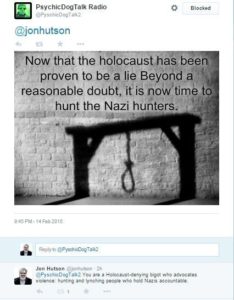

The Right Stuff doesn’t just offer quasi-irony, however, but also naked bigotry, as summarized by Anti-Fascist News:

[On The Right Stuff] they choose to openly use racial slurs, degrade women and rape survivors, mock the holocaust and call for violence against Jews. Their podcast, The Daily Shoah, which is a play on The Daily Show and the Yiddish term for The Holocaust, is a roundtable discussion of different racists broadcasting under pseudonyms. Here they do voice “impressions” of Jews, and consistently use terms like “Nig Nog,” “Muds[”] (referring to “mud races,” meaning non-white), and calling people of African descent “Dingos.” The N-word, homophobic slurs, and calls for enforced cultural patriarchy and heteronormativity are commonplace… The use of rhetoric like this is almost entirely missing from groups like American Renaissance, Counter-Currents, Radix Journal, Alternative Right, and even Stormfront, the main hub for racist groups who recently banned swastikas and racial slurs.24

Anti-Fascist News argues that different branches of the Alternative Right use different language to appeal to different target audiences. “The Right Stuff tries to mimic the aggression and reactionary insults of right-wing talk radio like Rush Limbaugh, while Radix would love to look a lot more like that trendy Critical Theory journal young grad students are clamoring to be published in.”25 This is more division of labor than factional conflict, as a number of Alt Right intellectual figures have appeared on The Right Stuff podcasts, for example.

Stylistic differences aside, though, Alt Rightists have also disagreed about substantive issues. One of the biggest points of contention has been whether White nationalists should work with Jews, or at least some Jews. Anti-Jewish bigotry and scapegoating have been prevalent across most of the movement, but with important variations and exceptions. For the minority of Alt Rightists who identify with neonazism, such as Andrew Anglin of the Daily Stormer, uncompromising antisemitism is the overriding core principle.26 And for many others, Jews are a major existential threat. To The Right Stuff blogger “Auschwitz Soccer Ref,” Jews as a group have engaged in “2,000 years of non-stop treachery and backstabbing” and are “remorseless enemies who seek the destruction of the people they hate, which is us.” As a result, “anyone who self-identifies as a Jew or anyone who makes excuses for a continued Jewish presence in White homelands should be unapologetically excluded from this movement, and none of these people should ever be allowed to speak at alt right conferences no matter how pro-White they may seem.”27

American Renaissance is a monthly online magazine considered widely to be a White supremacist publication.

Not all Alt Rightists agree. American Renaissance, one of the movement’s central institutions, pioneered a version of White nationalism that avoided antisemitism. Besides publishing Jewish authors, both Jews and antisemites have been welcome at AmRen events as long as they set aside their disagreements.28 Richard Spencer, too, repeatedly welcomed Jewish writers and cited them as useful contributors to the movement.

Even Alt Rightists who view Jews as dangerous outsiders don’t necessarily regard them as the embodiment of pure evil. Serbian-American author Srdja Trifkovic wrote that “the Jews” had disproportionately contributed to the erosion of European civilization. Nevertheless, he hoped for an alliance with Jews against their common enemy, “the brown, black, and yellow multitudes” whose eventual attacks on the Jewish community might “easily exceed in ferocity and magnitude the events of 1942-45.”29 Similarly, Counter-Currents writer M.K. Lane described Jews as “a self-segregating and culturally arrogant people, a people who refuse to assimilate [and] who even when they do ostensibly assimilate, cause even greater harm than they did before desegregating.” Yet Lane also hoped that a significant number of Jews could be won over to ally with White nationalism since, “if we go down, they go down.” Of course, in such an alliance White nationalists “must not allow ourselves to become stooges.” Jews “living in our midst… could either be allowed to live in their own communities, assimilate in small numbers, or move to Israel. Anything as long as they refrain from subverting our societies…”30

Manosphere

While White nationalism has been central to the Alternative Right, patriarchal politics have played an increasingly important—and increasingly poisonous—role in the movement. The original AlternativeRight.com featured a range of views on gender, from patriarchal traditionalism to a kind of quasi-feminism. A number of male contributors expressed concern that their branch of the Right had attracted few women. Publisher and novelist Alex Kurtagic argued in 2011 that women and men had distinct natural roles, but that the White nationalist movement needed both:

Women are far more than nurturers: they are especially proficient at networking, community building, consensus building, multi-tasking, and moral and logistical support provision. These are all essential in any movement involving community outreach and where user-friendly, low-key, non-threatening forms of recruitment are advisable…. Women can create a much broader comfort zone around hardcore political activism through organising a wide range of community, human, and support-oriented activities…31

Andrew Yeoman of Bay Area National Anarchists argued more pointedly that sexist behavior by male Alt Rightists was driving women away:

Many women won’t associate with our ideas. Why is this important? Because it leaves half our people out of the struggle. The women that do stick around have to deal with a constant litany of abuse and frequent courtship invitations from unwanted suitors. …nothing says ‘you’re not important to us’ [more] than sexualizing women in the movement. Don’t tell me that’s not an issue. I’ve seen it happen in all kinds of radical circles, and ours is the worst for it.32

Logo for the White nationalist discussion site, Stormfront

As the Alternative Right has grown, it has abandoned this kind of self-criticism and debate about gender politics. Going beyond traditionalist claims about the sanctity of the family and natural gender roles, Alt Rightists have embraced an intensely misogynistic ideology, portraying women as irrational, vindictive creatures who need and want men to rule over them and who should be stripped of any political role.33 The Traditionalist Youth Network claims that “women’s biological drives are contrary to the best interests of civilization and… the past century or so of women’s enfranchisement and liberation has been detrimental to societal stability.” But the group frames this position as relatively moderate because, unlike some rightists, they don’t believe “that women are central to the destruction of Western Civilization”—they are simply being manipulated by the Jews.34 The Daily Stormer has banned female contributors and called for limiting women’s roles in the movement, sparking criticism from women on the more old school White nationalist discussion site Stormfront. Far-right blogger Matt Forney asserts that “Trying to ‘appeal’ to women is an exercise in pointlessness…. it’s not that women should be unwelcome [in the Alt Right], it’s that they’re unimportant.”35

A big reason for this shift toward hardline woman-hating is that the Alt Right has become closely intertwined with the so-called manophere, an online antifeminist male subculture that has grown rapidly in recent years, largely outside traditional right-wing networks. The manosphere includes various overlapping circles, such as Men’s Rights Activists (MRAs), who argue that the legal system and media unfairly discriminate against men; Pickup Artists (PUAs), who help men learn how to manipulate women into having sex with them; Men Going Their Own Way (MGTOWs), who protest women’s supposed dominance by avoiding relationships with them; and others.36

Manospherians have emphasized male victimhood—the false belief that men in U.S. society are oppressed or disempowered by feminism or by women in general. This echoes the concept of “reverse racism,” the idea that White Americans face unfair discrimination, which White nationalists have promoted since the 1970s.

Daryush Valizadeh writes at the PUA site, Return of Kings.

Some manospherians are family-centered traditionalists while others celebrate a more predatory sexuality. Daryush Valizadeh, who writes at the PUA site Return of Kings under the name Roosh V, embodies this tension. He argues that the nuclear family with one father and one mother is the healthiest unit for raising children, and socialism is damaging because it makes women dependent on the government and discourages them from using their “feminine gifts” to “land a husband.” Yet Valizadeh has also written 10 how-to books for male sex tourists with titles such as Bang Ukraine and Bang Iceland. Valizadeh doesn’t dwell on his own glaring inconsistency, but does suggest in his article, “What is Neomasculinity?,” that the dismantling of patriarchal rules has forced men to pursue “game” as a defensive strategy “to hopefully land some semblance of a normal relationship.”37

Like the Alt Right, manosphere discourse ranges from intellectual arguments to raw invective, although the line between them is often blurred. Paul Elam’s A Voice for Men, founded in 2009, became one of the manosphere’s most influential websites with intentionally provocative articles arguing, for example, that the legal system was so heavily stacked against men that rape trial jurors should vote to acquit “even in the face of overwhelming evidence that the charges are true.”38 Elam also “satirically” declared October “Bash a Violent Bitch Month,” urging men to fight back against physically abusive female partners. He offered “satire” such as:

I don’t mean subdue them, or deliver an open handed pop on the face to get them to settle down. I mean literally to grab them by the hair and smack their face against the wall till the smugness of beating on someone because you know they won’t fight back drains from their nose with a few million red corpuscles.39

Manospherians also tend to promote homophobia and transphobia, which is consistent with their efforts to re-impose rigid gender roles and identities. At Return of Kings, Valizadeh has denounced the legalization of same-sex marriage as “one phase of a degenerate march to persecute heterosexuals, both legally and socially, while acclimating young children to the homosexual lifestyle.”40 On the same website, Matt Forney warned that trans women who have sex with cis men might be guilty of “rape by fraud.”41 At the same time, some manosphere sites have sought to reach out to gay men. A Voice for Men published a series of articles by writer Matthew Lye that were later collected into the e-book The New Gay Liberation: Escaping the Fag End of Feminism, which Paul Elam described as “a scorching indictment of feminist hatred of all things male.”42

One of the events that brought the manosphere to public attention was the Gamergate controversy. Starting in 2014, a number of women who worked in—or were critical of sexism in—the video game industry were subjected to large-scale campaigns of harassment, coordinated partly with the #Gamergate Twitter hashtag. Supporters of Gamergate claimed that that campaign was a defense of free speech and journalistic ethics and against political correctness, but it included streams of misogynistic abuse, rape and death threats, as well as doxxing (public releases of personal information), which caused several women to leave their homes out of fear for their physical safety.43 The Gamergate campaign took the pervasive, systematic pattern of threats and abuse that has been long used to silence women on the internet, and sharpened it into a focused weapon of attack.44 Gamergate, in turn, strongly influenced the Alt Right’s own online activism, as I discuss below.

There is significant overlap between the manosphere and the Alt Right. Both are heavily active on discussion websites such as 4chan, 8chan, and Reddit, and a number of prominent Alt Rightists—such as Forney, Theodore Beale (pseudonym: “Vox Day”), James Weidmann (“Roissy”), and Andrew Auernheimer (“weev”)—have also been active in the manosphere. Many other Alt Rightists have absorbed and promoted manosphere versions of gender ideology.

Daryush “Roosh” Valizadeh in Warsaw, Poland in 2014. (Photo: Bartek Kucharczyk via Wiki Commons).

But there have also been tensions between the two rightist movements. In 2015, Valizadeh (“Roosh V”) began to build a connection with the Alternative Right, attending an NPI conference and quoting extensively from antisemite Kevin MacDonald in a lengthy post about “The Damaging Effects of Jewish Intellectualism And Activism On Western Culture.”45 Some Alt Rightists responded favorably. One blogger commented that the manosphere was “not as stigmatized” as White nationalism and the Alt Right, and suggested hopefully that, “since the Manosphere has a very broad appeal it is possible that bloggers such as Roosh and Dalrock [a Christian manospherian] might serve as a stepping stone to guide formerly apathetic men towards the Alternative Right.”46 Matt Parrott of the Traditionalist Youth Network praised Valizadeh’s “What is Neomasculinity?” as “a masterful synthesis of human biodiversity knowledge, radical traditionalist principle, and pragmatic modern dating experience.”47

But the relationship soured quickly, largely because Valizadeh is Persian American. Although Andrew Anglin of The Daily Stormer tweeted that Valizadeh was “a civilized and honorable man,”48 many White nationalists denounced him as non White and an enemy. One tweeted that he was “a greasy Iranian” who “goes to Europe to defile white women and write books about it.”49 After studying Valizadeh’s accounts of his own sex tourism, Counter-Currents Publishing editor-in-chief Greg Johnson concluded that Roosh “is either a rapist or a fraud” and “it is not just feminist hysteria to describe Roosh as a rape advocate.” More broadly, Johnson wrote, “for all its benefits… the manosphere morally corrupts men. It does not promote the resurgence of traditional and biologically based sexual norms.”50 Valizadeh responded by blogging “The Alt Right Is Worse Than Feminism in Attempting to Control Male Sexual Behavior.”51

Male tribalism

Jack Donovan, an early contributor to AlternativeRight.com who has stayed active in the Alt Right as it has grown, offers a related but distinct version of male supremacist ideology. In a series of books and articles over the past decade, Donovan has advocated a system of patriarchy based on “tribal” comradeship among male warriors. Drawing on evolutionary psychology, he argues that in the past men have mostly organized themselves into small, close-knit “gangs,” which fostered true masculinity and men’s natural dominance over women. Yet modern “globalist civilization” “requires the abandonment of human scale identity groups for ‘one world tribe.’” A combination of “feminists, elite bureaucrats, and wealthy men,” he writes, has promoted male passivity and put women in a dominant role.52

Jack Donovan has advocated a system of patriarchy based on “tribal” comradeship among male warriors. (photo: Zachary O. Ray via Wiki Commons).

Unlike Christian rightists, who argue that feminism misleads women into betraying their true interests, Donovan sees feminism as an expression of women’s basic nature, which is “to calm men down and enlist their help at home, raising children, and fixing up the grass hut.” Today, he argues, feminists’ supposed alliance with globalist elites reflects this: “Women are better suited to and better served by the globalism and consumerism of modern democracies that promote security, no-strings attached sex and shopping.”53

Donovan’s social and political ideal is a latter-day tribal order that he calls “The Brotherhood,” in which all men would affirm their sacred loyalty to each other against the outside world. A man’s position would be based on “hierarchy through meritocracy,” not inherited wealth or status. All men would be expected to train and serve as warriors, and only warriors—meaning no women—would have a political voice. In this version of patriarchal ideology, unlike the Christian Right version, male comradeship is central and the family is entirely peripheral. An example of the kind of community Donovan envisions is the Odinist group Wolves of Vinland, which Donovan joined after visiting their off-the-grid community in rural Virginia in 2014. The Wolves use group rituals (including animal sacrifice) and hold fights between members to test their masculinity.54 The Wolves of Vinland have also been praised by White nationalist groups such as Counter-Currents Publishing, and one of their members has been imprisoned for attempting to burn down a Black church in Virginia.55

Donovan has written that he is sympathetic to White nationalist aims such as encouraging racial separatism and defending European Americans against “the deeply entrenched anti-white bias of multiculturalist orthodoxies.” White nationalism dovetails with his beliefs that all humans are tribal creatures and human equality is an illusion. But in contrast to most Alt Rightists, race is not Donovan’s main focus or concern. “My work is about men. It’s about understanding masculinity and the plight of men in the modern world. It’s about what all men have in common.” His “Brotherhood” ideal is not culturally specific and he’s happy to see men of other cultures pursue similar aims. “For instance, I am not a Native American, but I have been in contact with a Native American activist who read The Way of Men and contacted me to tell me about his brotherhood. I could never belong to that tribe, but I wish him great success in his efforts to promote virility among his tribesmen.”57

Donovan also echoes the 1909 Futurist Manifesto, a document that prefigured Italian Fascism. (Image: Wiki Commons)

There are strong resonances between Donovan’s ideas and early fascism’s violent male camaraderie, which took the intense, trauma-laced bonds that World War I veterans had formed in the trenches and transferred them into street-fighting formations such as the Italian squadristi and German storm troopers. Donovan also echoes the 1909 Futurist Manifesto, a document that prefigured Italian Fascism with statements such as “We want to glorify war—the only cure for the world—militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of the anarchists, the beautiful ideas which kill, and contempt for woman.”58 Thus it’s not surprising he has embraced the term “anarcho-fascism,” referring to “a unified male collective… bound together by a red ribbon of blood.”59

In the Alternative Right and among rightists in general, the most controversial part of Donovan’s ideology is that he advocates and practices “androphilia,” by which he means love or sex between masculine men. Donovan doesn’t call himself gay, rejects gay culture as effeminate, and justifies homophobia as a defense of masculinity rooted in the male gang’s collective survival needs. His version of homosexuality is a consummation of the priority that men in his ideal gang place on each other. As he has commented, “When you get right down to it, when it comes to sex, homos are just men without women getting in the way.”60 Many Alternative Rightists consider homosexuality in any form to be immoral and a threat to racial survival, and Donovan has been vilified on many Alt Right sites for his sexuality, yet his work has also won widespread support within the movement. Anti-Fascist News has noted a broader trend among many White nationalists to include openly homosexual writers (such as James O’Meara) and musicians (such as Death in June leader Douglas Pearce), while continuing to derogate gay culture.61

Right-wing anarchists

Like many far-right currents in the United States, the Alt Right offers a vision of the state that is both authoritarian and decentralist. Alt Rightists uphold classical fascism’s elitist and anti-democratic views on how society should be governed, and as the movement has grown it has increasingly applauded dictatorial figures such as Chile’s Augusto Pinochet.62 At the same time, the Alt Right goal of breaking up the United States into ethnically separate polities is inherently decentralist, and is rooted in both the European New Right’s vision of replacing nation-states with a federated “empire” and paleoconservatism’s traditional hostility to big government. The authoritarian/decentralist blend has been bolstered by two other political currents that have influenced the Alt Right: right-wing anarchism and neoreaction.

As part of its project to bring together a range of dissident right-wing voices, AlternativeRight.com published articles by self-identified anarchists Andrew Yeoman of Bay Area National Anarchists (BANA) and Keith Preston of the website Attack the System (ATS). National-Anarchism, which advocates a decentralized system of “tribal” enclaves, was initiated in the 1990s by Troy Southgate, a veteran of British neonazism.63 Over the following years, National-Anarchist groups formed in a number of countries across Europe, the Americas, and Australia/New Zealand. The first U.S. affiliate, BANA, began in 2007, and Southgate formally launched the National-Anarchist Movement (N-AM) in 2010.64

National-Anarchism is a White nationalist ideology. Like Identitarianism, it draws heavily on the ENR doctrine that ethnic and racial separatism is needed to defend so-called biocultural diversity. The N-AM Manifesto declares that race categories are basic biological facts and some people are innately superior to others. National-Anarchists also repeat classic antisemitic conspiracy theories and, like many neonazis, promote neopaganism and closeness to nature.65 But National-Anarchists reject classical fascism for its emphasis on strong nation-states, centralized dictatorship, and collaboration with big business. Instead, they call for breaking up society into self-governing tribal communities, so that different cultures, beliefs, and practices can co-exist side by side.66

National-Anarchism is a White nationalist ideology. Like Identitarianism, it draws heavily on the ENR doctrine that ethnic and racial separatism is needed to defend so-called biocultural diversity. The N-AM Manifesto declares that race categories are basic biological facts and some people are innately superior to others. National-Anarchists also repeat classic antisemitic conspiracy theories and, like many neonazis, promote neopaganism and closeness to nature.65 But National-Anarchists reject classical fascism for its emphasis on strong nation-states, centralized dictatorship, and collaboration with big business. Instead, they call for breaking up society into self-governing tribal communities, so that different cultures, beliefs, and practices can co-exist side by side.66

National-Anarchists have not had a significant presence in the Alternative Right since BANA disbanded in 2011, but self-described anarcho-pluralist Keith Preston has continued to participate in Alt Right forums, for example speaking at National Policy Institute conferences and on The Right Stuff podcasts. Preston is a former left-wing anarchist who moved to the Right in the 1990s and then founded the group American Revolutionary Vanguard, which is better known today by the name of its website, Attack the System.67 ATS brings together a number of right-wing currents, including National-Anarchist, libertarian, White nationalist, Duginist, and others, among it editors and contributors, but Preston’s own ideology is distinct from all of these.68

Like the National-Anarchists, Preston advocates a decentralized, diverse network of self-governing communities, while rejecting left-wing anarchism’s commitment to dismantle social hierarchy and oppression. Authoritarian and supremacist systems would be fully compatible with the anarcho-pluralist model, as long as they operated on a small scale. But unlike National-Anarchists, Preston frames his decentralist ideal in terms of individual free choice rather than tribalism, and he is not a White nationalist.69 Although Preston has echoed some racist ideas such as the claim that non-European immigrants threaten to destroy Western civilization, his underlying philosophy is based not on race but rather a generic, Nietzschean elitism that is not ethnically specific.70 While Preston himself is White, several of his closest associates in the Attack the System inner circle are people of color.

Preston has offered several reasons for his involvement in the Alternative Right. He sees the movement as an important counterweight to what he calls “totalitarian humanism” (supposedly state-enforced progressive values, i.e., political correctness), he regards the Alt Right’s foreign policy non-interventionism and economic nationalism as superior to what the Republican or Democratic parties advocate, and he shares many Alt Rightists’ interest in earlier European “critics of liberal capitalism and mass democracy,”71 meaning people like Julius Evola, Carl Schmitt, and Ernst Jünger. In addition, the Alt Right allows Preston to avoid political isolation, as his efforts to reach out to left-wing anarchists have been almost completely rejected.

Preston is a respected figure within the Alternative Right, and his anti-statist vision appeals to some White nationalists in the movement. For example, Counter-Currents author Francisco Albanese has argued that it provides “the best and most viable option for the ethnic and racial survival” of Whites in regions where they form a minority of the population. In addition, “it is only outside the state that whites can come to understand the true essence of community and construction of a common destiny.”72 At the same time, anarcho-pluralism offers potential common ground between White nationalists and other critics of the existing order, such as anarcho-capitalists and other “market anarchists,” whose ideas are regularly featured on Attack the System, as well as the “libertarian theocrats” of the Christian Reconstructionist movement.73

Preston’s approach to political strategy takes this bridge-building further. Echoing Third Position fascists, who denounce both communism and capitalism, Preston and ATS call for a broad revolutionary alliance of all those who want to destroy U.S. imperialism and the federal government. Within U.S. borders, this would involve a “pan-secessionist” strategy uniting groups across the political spectrum that want to carve out self-governing enclaves free of federal government control.74 As a step in this direction, ATS supported a series of North American secessionist conventions, which brought together representatives of the neo-Confederate group League of the South, the Reconstructionist-influenced Christian Exodus, the libertarian Free State Project, advocates of Hawaiian independence, the left-leaning Second Vermont Republic, and others.75

Neoreaction

Neoreaction is another dissident right-wing current with a vision of small-scale authoritarianism that has emerged online in the past decade, which overlaps with and has influenced the Alternative Right. Like the Alt Right and much of the manosphere, neoreaction (often abbreviated as NRx, and also known as Dark Enlightenment) is a loosely unified school of thought that rejects egalitarianism in principle, argues that differences in human intelligence and ability are mainly genetic, and believes that cultural and political elites wrongfully limit the range of acceptable discourse. Blogger Curtis Yarvin (writing under the pseudonym Mencius Moldbug) first articulated neoreactionary ideology in 2007, but many other writers have contributed to it. Neoreaction emphasizes order and restoring the social stability that supposedly prevailed before the French Revolution, along with technocratic and futurist concerns such as transhumanism, a movement that hopes to radically “improve” human beings through technology. NRx theorist Nick Land is a leading advocate of accelerationism, which in his version sees global capitalism driving ever-faster technological change, to the point that artificial intelligence essentially replaces human beings. One critic wrote that neoreaction “combines all of the awful things you always suspected about libertarianism with odds and ends from PUA culture, Victorian Social Darwinism, and an only semi-ironic attachment to absolutism. Insofar as neoreactionaries have a political project, it’s to dissolve the United States into competing authoritarian seasteads on the model of Singapore…”76

PayPal co-founder and Trump supporter Peter Thiel. (Photo by JD Lasica via Flickr.)

Neoreactionaries, who are known for their arcane, verbose theoretical monologues, appear to be mostly young, computer-oriented men, and their ideas have spread partly through the tech startup scene. PayPal co-founder and Trump supporter Peter Thiel has voiced some neoreactionary-sounding ideas. In 2009, for example, he declared, “I no longer believe that freedom and democracy are compatible” and “the vast increase in welfare beneficiaries and the extension of the franchise to women…have rendered the notion of ‘capitalist democracy’ into an oxymoron.”77 Both Yarvin and fellow NRxer Michael Anissimov have worked for companies backed by Thiel.78 This doesn’t necessarily mean that Thiel is intentionally bankrolling the neoreactionary movement per se, but it points to resonances between that movement and Silicon Valley’s larger techno-libertarian discourse.

“At its heart, neoreaction is a critique of the entire liberal, politically-correct orthodoxy,” commented “WhiteDeerGrotto” on the NRx blog Habitable Worlds. “The Cathedral, a term coined by Moldbug, is a description of the institutions and enforcement mechanisms used to propagate and maintain this orthodoxy”—a power center that consists of Ivy League and other elite universities, The New York Times, and some civil servants. “The politically-correct propagandists assert that humans are essentially interchangeable, regardless of culture or genetics, and that some form of multicultural social-welfare democracy is the ideal, final political state for all of humanity. Neoreaction says no. The sexes are biologically distinct, genetics matter, and democracy is deeply flawed and fundamentally unstable.”79

While Alt Rightists largely agree with these neoreactionary ideas, and some outsiders have equated the two movements, Alt Right and neoreaction differ significantly. Alt Rightists might or might not invoke popular sovereignty as an achievement of European civilization, and try to strike a populist or anti-elitist pose, but neoreactionaries all regard regular people as utterly unsuited to hold political power—“a howling irrational mob” as NRx theorist Nick Land has put it.80 Some NRxers advocate monarchy; others want to turn the state into a corporation with members of an intellectual elite as shareholders.81 Conversely, neoreactionaries might or might not translate their genetic determinism into calls for racial solidarity, but for most Alt Rightists race is the basis for everything else.82 Unlike most Alt Rightists, leading neoreactionaries have not supported Donald Trump.83 In addition, while many Alt Rightists emphasize antisemitism, neoreactionaries generally do not, and some neoreactionaries are Jewish or, in Yarvin’s case, of mixed Jewish and non-Jewish ancestry.84 Indeed, in The Right Stuff’s lexicon of Alt Right terminology, “Neoreaction” translates as “Jews.”

At the same time, many Alt Rightists regard neoreaction as a related movement that offers many positive contributions. Some writers, such as Steve Sailer, have had a foot in both camps. Alt Rightist Gregory Hood has argued that White nationalism and neoreaction are complementary: “I’ve argued in the past that race is sufficient in and of itself to serve as a foundation for state policy. However, just saying that tells you very little about how precisely you execute that program. NRx and its theoretical predecessors are absolutely core to understanding how society works and how power functions.”85 Anarcho-pluralist Keith Preston applauded a proposal by NRxer Michael Anissimov to create breakaway enclaves in “low-population, defensible regions of the United States like Idaho.”86 On its own, neoreaction seems too esoteric to have much of a political impact, but its contribution to Alt Right ideology might be significant.

PART 3 – RELATIONSHIP WITH DONALD TRUMP

Political strategy debates

The Alternative Right first gained mainstream attention through its support for Donald Trump’s presidential candidacy. In exploring the Alt Right’s relationship with the Trump campaign and with Trump as president-elect, several issues deserve special attention: the movement’s debates about political strategy, its skillful use of online activism, and its attraction of a wider circle of sympathizers and popularizers who came to be known as the “Alt Lite.”

Alt Rightists’ embrace of Trump followed several years in which they argued about whether to work within existing political channels or reject them entirely. During this period, American Renaissance columnist Hubert Collins called on White nationalists to use the electoral process and ally with more mainstream anti-immigrant groups to keep Whites at as high a percentage of the U.S. population as possible.87 In contrast, Gregory Hood of Counter-Currents Publishing declared that the United States was “beyond reform” and political secession was “the only way out.” Sidestepping this issue, many Alt Rightists have followed the European New Right lead and focused on a “metapolitical” strategy of seeking to transform the broader culture. In Lawrence Murray’s words, “When the idea of White nationalism has taken root among enough of our people, the potential to demand, demonstrate, and act will be superior to what it currently is.”89 Jack Donovan has argued that the U.S. is on the road to becoming a failed state and urged Alt Rightists to “build the kinds of resilient communities and networks of skilled people that can survive the collapse and preserve your identities after the Fall.”90 To Donovan, this is an optimistic scenario: “In a failed state, we go back to Wild West rules, and America becomes a place for men again—a land full of promise and possibility that rewards daring and ingenuity, a place where men can restart the world.”91

Donald Trump speaking to supporters in Phoenix, Arizona, 2016.

(Photo: Gage Skidmore via Flickr).

Whether or not to work within established political channels has been debated at movement events, with some Alt Rightists moving from one position to another. Richard Spencer, for example, argued in 2011 that “the GOP could unite a substantial majority of white voters by focusing its platform on immigration restriction.” This strategy “would…ensure that future Americans inherit a country that resembles that of their ancestors.” But two years later, Spencer seemingly turned his back on the Republican Party and called for creating a separate White ethnostate in North America. He declared, “the majority of children born in the United States are non-White. Thus, from our perspective, any future immigration-restriction efforts are meaningless.” Spencer also argued that “restoring the Constitution,” (going back to an aristocratic republic run by property-owning White men) as some White nationalists advocated, would only lead to a similar or worse situation.

One approach has been to propose working within the system in order to weaken it, advocating changes that sound reasonable but require radical change—a right-wing version of the Trotskyist transitional demand strategy. Ted Sallis, for example, urged White nationalists to “demand a seat at the multicultural table, represented by real advocates of White interests, not groveling patsies.” This would involve using the language of multiculturalism to complain about “legitimate” cases of discrimination against Whites or members of other dominant groups. The aim here would not be “reforming the System. It is instead using the contradictions and weaknesses of the System against itself…”94

The Traditionalist Youth Network is a White nationalist group founded in 2013 by Matthew Heimbach.

To a large extent, Alternative Rightist support for Trump’s presidential candidacy followed a related approach of using the system against itself. Alt Rightists began praising Trump in 2015, and by mid-2016 most of the movement was applauding him. But this support was qualified by the recognition that Trump was not one of them and was not going to bring about the change they wanted. Brad Griffin, who blogs at Occidental Dissent under the name Hunter Wallace, hoped in late 2015 that Trump “provokes a fatal split that topples the GOP.” The Traditionalist Youth Network declared:

While Donald Trump is neither a Traditionalist nor a White nationalist, he is a threat to the economic and social powers of the international Jew. For this reason alone as long as Trump stands strong on deportation and immigration enforcement we should support his candidacy insofar as we can use it to push more hardcore positions on immigration and Identity. Donald Trump is not the savior of Whites in America, he is however a booming salvo across the bow of the Left and Jewish power to tell them that White America is awakening, and we are tired of business as usual.96

At The Right Stuff, “Professor Evola-Hitler” argued that Trump had broken important taboos on issues such as curtailing immigration and ending birthright citizenship, damaged the Republican Party’s pro-Israel coalition, shifted the party closer to ethnic nationalism, and “offers the opportunity for the Alt-Right to expand quickly,” but cautioned that “We need to be taking advantage of Trump, not allow Trump to take advantage of us.”97

Not all Alt Rightists supported Trump. The Right Stuff contributor “Auschwitz Soccer Ref” argued that Alt Rightists shouldn’t support Trump since two of his children had married Jews, making him “naturally loyal” to Israel.98 Jack Donovan suggested that a Hillary Clinton presidency would be preferable, because she would “drive home the reality that white men are no longer in charge… and that [the United States] is no longer their country and never will be again,”99 Keith Preston commented, “The alt-right’s attachment to Trump seems to be a mirror image repeat of the religious right’s attachment to Reagan, i.e. the case of an insurgent, somewhat reactionary, populist movement being taken for a ride by a thoroughly pro-ruling class centrist politician motivated primarily by personal ambition.”100 However, these anti-Trump voices were squarely in the minority.

Internet memes and harassment campaigns

Alt Rightists also turned online harassment and abuse into a potent tactic for frightening and silencing opponents. Photo: Sebastian via Flickr.

The main way that Alt Rightists helped Trump’s campaign was through online activism. A pivotal example came in the summer of 2015, when Alt Rightists promoted the #cuckservative meme to attack Trump’s GOP rivals as traitors and sellouts to liberalism. “Cuckservative” combines the words “conservative” and “cuckold,” meaning a man whose wife has sex with other men. As journalist Joseph Bernstein pointed out, “The term’s connotations are racist. By alluding to a genre of porn in which passive white husbands watch their wives have sex with black men, it casts its targets as impotent defenders of white people in America.”101 During the weeks leading up to the first Republican presidential debate, Alt Rightists spread the meme across social media to boost Trump and vilify his GOP rivals, as in a Tweet that showed a picture of Jeb Bush with the words, “Please fuck my country, Mexico. #Cuckservative.”102 As Anti-Fascist News pointed out, this initiative “allowed racialist discourse to shift into the public, making #cuckservative an accusation that mainstream Republicans feel like they have to answer to.”103

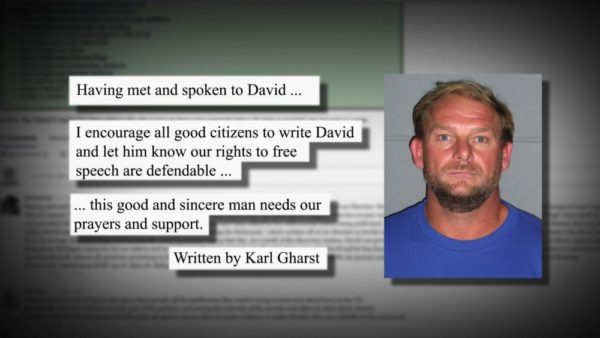

Alt Rightists also turned online harassment and abuse into a potent tactic for frightening and silencing opponents, borrowing directly from the manosphere’s Gamergate campaign discussed above. In the Spring of 2016, for example, anti-Trump protesters at Portland State University were flooded with racist, transphobic, and antisemitic messages, doxxing, and rape and death threats, sent from anonymous social media accounts. Reflecting the manosphere’s influence, Alt Right harassment often emphasized sexual violence and the humiliation of women and girls, even when men were the supposed targets.104 David French, staff writer at the conservative National Review, described the yearlong stream of relentless online abuse his family has endured because he criticized Trump and the Alt Right:

I saw images of my daughter’s face in gas chambers, with a smiling Trump in a Nazi uniform preparing to press a button and kill her. I saw her face photoshopped into images of slaves. She was called a “niglet” and a “dindu.” The alt-right unleashed on my wife, Nancy, claiming that she had slept with black men while I was deployed to Iraq, and that I loved to watch while she had sex with “black bucks.” People sent her pornographic images of black men having sex with white women, with someone photoshopped to look like me, watching.105

PULSE Nightclub sign in Orlando (photo: Daniel Ruyter via Flickr).

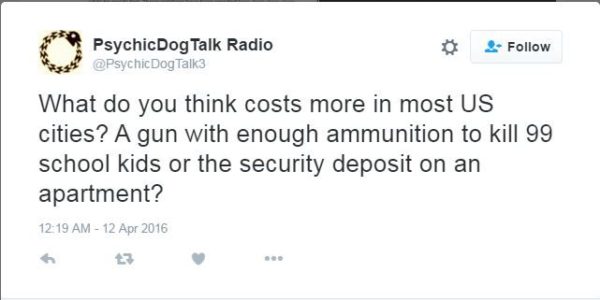

Another example of Alt Right online activism was the campaign to “wedge gays and Muslims,” as “Butch Leghorn” of The Right Stuff put it. Writing in June 2016, two days after Afghani American Omar Mateen murdered 49 people at a gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida, Leghorn declared, “Gays will never be safe from Muslim violence, and the liberals will allow Muslim violence against gays because Muslims are higher ranked on the Progressive stack than gays…. This makes [the Orlando] shooting a very valuable wedge issue. By allowing Muslims into America, the Democrats are in effect choosing Muslims over gays. We simply need to hammer this issue. Meme magic is real boys, so spread this meme. Drive this wedge. Smash their coalition.”106 Leghorn offered several examples of talking points and images to use, such as a rainbow flag with the words “Fuck Islam” superimposed over it.

One of the Alt Right’s most skillful uses of social media in 2016 was the #DraftOurDaughters meme, which was trending on Twitter the week before the election. As the website Know Your Meme explained, “#DraftOurDaughters is a satirical social media hashtag launched by supporters of Donald Trump which encourages American women to register for Selective Service in preparation for hypothetical scenarios of United States military operations that would supposedly be launched by Hillary Clinton if she were elected as President of the United States.” The campaign included a series of fake Clinton campaign ads, many of which feature images of women in military uniform and slogans such as “Hillary will stand up to Russian Aggression. Will you stand with her?,” “I’d rather die in a war than live under bigotry,” and “In the White House or on Russian soil. The fight for equality never stops.”107

The Daily Stormer is White supremacist news and commentary website edited by Andrew Anglin.

#DraftOurDaughters portrayed the Clinton campaign as fusing feminism/multiculturalism and aggressive militarism. Since that was a reasonably accurate description of Clinton’s politics, the meme was equally effective as either disinformation or satire. A number of Alt Right sites, such as Vox Popoli and The Daily Stormer, promoted the campaign.108 Along with spreading the “ads” themselves, Alt Rightists also spread the phony claim that mainstream media had been taken in by them.109

The Alt Lite

As the Alt Right has grown and attracted increased attention, it has also developed complicated relationships with more moderate rightists. The movement has largely defined itself and drawn energy by denouncing conservatives, and some conservatives have returned the favor, such as the prestigious National Review.110 At the same time, other conservatives have taken on the role of apologists or supporters for the Alt Right, helping to spread a lot of its message without embracing its full ideology or its ethnostate goals. Richard Spencer and his comrades began to call this phenomenon the “Alt Right-lite” or simply the “Alt Lite.” Alt Rightists have relied on the Alt Lite to help bring its ideas to a mass, mainstream audience, but to varying degrees they have also regarded Alt Lite figures with resentment, as ideologically untrustworthy opportunists.

Breitbart News Network is the preeminent example of Alt Lite politics. Founded in 2007, Breitbart featured sensationalist attacks on liberals and liberal groups, praise for the Tea Party’s anti-big government populism, and aggressive denials that conservatives were racist, sexist, or homophobic. Under Steve Bannon, who took over leadership in 2012, the organ began to scapegoat Muslims and immigrants more directly.111 In March 2016, Breitbart published “An Establishment Conservative’s Guide to the Alt-Right,” by Allum Bokhari and Milo Yiannopoulos, which asserted—without evidence—that most Alt Rightists did not believe their own racist propaganda, but were actually just libertarians trying to shock people.112 The article helped boost the Alt Right’s profile and acceptability in mainstream circles, yet many Alt Rightists criticized it for glossing over their White nationalist ideology.113

Breitbart News Network is the preeminent example of Alt Lite politics. Founded in 2007, Breitbart featured sensationalist attacks on liberals and liberal groups, praise for the Tea Party’s anti-big government populism, and aggressive denials that conservatives were racist, sexist, or homophobic. Under Steve Bannon, who took over leadership in 2012, the organ began to scapegoat Muslims and immigrants more directly.111 In March 2016, Breitbart published “An Establishment Conservative’s Guide to the Alt-Right,” by Allum Bokhari and Milo Yiannopoulos, which asserted—without evidence—that most Alt Rightists did not believe their own racist propaganda, but were actually just libertarians trying to shock people.112 The article helped boost the Alt Right’s profile and acceptability in mainstream circles, yet many Alt Rightists criticized it for glossing over their White nationalist ideology.113

Milo Yiannopoulos. (Photo by Kmeron for LeWeb13 Conference via Flickr.)

Over the following months, Yiannopoulos—a flamboyantly gay man of Jewish descent and a political performer who vilifies Muslims and women and refers to Donald Trump as “Daddy”—became publicly identified with the Alt Right himself, to mixed reviews from Alt Rightists.114 Meanwhile, Steve Bannon declared Breitbart “the platform of the Alt Right” and began publishing semi-veiled antisemitic attacks on Trump’s opponents, all while insisting that White nationalists, antisemites, and homophobes were marginal to the Alt Right.115 Richard Spencer was pleased when Donald Trump hired Bannon to run his campaign, commenting that “Breitbart has acted as a ‘gateway’ to Alt Right ideas and writers” and that the media outlet “has people on board who take us seriously, even if they are not Alt Right themselves.”116 But other Alt Rightists have been more critical of the Alt Lite phenomenon. At Occidental Dissent, Brad Griffin describes the Alt Lite as “basically conservative websites pushing Alt-Right material in order to generate clicks and revenue,” and asks, “What the hell does Milo Yiannopoulos—a Jewish homosexual who boasts about carrying on interracial relationships with black men—have to do with us?”117

CONCLUSION: THE ALT RIGHT AND THE TRUMP PRESIDENCY

Most Alt Rightists were thrilled by Trump’s upset victory over Hillary Clinton, but not because they believe that Trump shares their politics or will bring about the changes that they want. Rather, they believe a Trump presidency will offer them “breathing room” to promote their ideology and to “move the Overton window” in their favor.118 In turn, they see themselves as the Trump coalition’s political vanguard, taking hardline positions that pull Trump further to the right while enabling him to look moderate by comparison. In Richard Spencer’s words, “The Alt Right and Trumpian populism are now aligned much in the way the Left is aligned with Democratic politicians like Obama and Hillary…. We—and only we—can say the things Trump can’t say . . . can criticize him in the right way . . . and can envision a new world that he can’t quite grasp.”119 The Traditionalist Youth Network was more specific: “We cannot and will not back down on the Jewish Question or our explicit racial identity. We won’t. Don’t worry. But we will join those who aren’t as radical as we are in pulling politics in our direction.”120