Security and the Fourth International

The Smith Act trial and government infiltration of the Trotskyist movement—Part one

By

Eric London

8 December 2016

Seventy five years ago, on December 8, 1941, 18 Trotskyists were sentenced to prison terms for advocating the overthrow of the US government. The following two-part article is based on information gathered from the valuable book Trotskyists on Trial: Free Speech and Political Persecution Since the Age of FDR, by Donna T. Haverty-Stacke. In addition, the articles draw from the World Socialist Web Site’s independent investigation of thousands of pages of trial transcripts, SWP archive material, and previously unavailable FBI records brought to light by Haverty-Stacke.

In 1941, the Roosevelt administration launched one of the most important political trials in the history of the United States when it charged 29 members of the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) with sedition and conspiracy to overthrow the government. FBI agents raided the party’s offices in Minneapolis on June 27 and prosecutors convened a grand jury shortly thereafter. On October 27, the trial began in federal court. Its proceedings lasted more than one month.

The Socialist Workers Party was aligned politically with the Fourth International at the time of the trial. It was singled out for prosecution as the United States prepared to enter the world war in Europe and East Asia.

The defendants used the trial to present the party’s socialist principles to a broad audience. They defended the SWP’s opposition to imperialist war from the witness stand and refuted the prosecution’s attempt to portray socialist revolution as a conspiratorial coup d’état. They conducted themselves in a courageous and principled manner, with federal prison sentences hanging over their heads. The SWP published the trial transcript of SWP National Chairman James P. Cannon’s spirited testimony in the 1942 pamphlet Socialism on Trial.

On December 1, the jury found 18 of the defendants guilty of violating the newly enacted Smith Act, but recommended leniency in sentencing. On December 8, one day after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the trial judge read “the 18” their sentences, which ranged from 12 to 16 months. On November 22, 1943, the Supreme Court refused to take the appeal lodged by the defendants. The next month, the 18 surrendered themselves to federal authorities and began serving their sentences. Despite a national campaign that generated support from thousands of workers and many prominent intellectuals and attorneys, Roosevelt refused to pardon the defendants. Six of the 18 were released after six months, and the remaining 12 were released in January 1945 after serving one year.

This significant event in the history of the socialist movement is the subject of a new book published 75 years after the trial by Hunter College Professor Donna Haverty-Stacke. The book, titled Trotskyists on Trial: Free Speech and Political Persecution Since the Age of FDR (New York University Press, 2016), is a significant work and its author is to be congratulated on her accomplishment. Haverty-Stacke has not only taken up a subject that has been ignored by academia, she has also brought to light many previously unknown details of the prosecution and its political and legal ramifications.

Haverty-Stacke has undertaken a painstaking review of previously unexamined or unavailable archived material from the Department of Justice and the Federal Bureau of Investigation. This material has been largely unexplored by academics, who have all but ignored (with the notable exception of Bryan Palmer’s biography of James P. Cannon and his history of the 1934 Minneapolis General Strike) the significant role of Trotskyism in American political life.

It is a welcome development that Haverty-Stacke’s book provides a wealth of new information regarding the extent of the penetration of the Trotskyist movement by FBI agents and informants. She presents the discussions taking place within the Roosevelt administration as it prepared the first peacetime sedition prosecution since those following the passage of the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798. She addresses the legal issues involved in the trial, the appeal before the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals, and the case’s precedential role in laying the foundation for further anti-communist trials in the 1940s and 1950s. She begins by providing the backdrop to the trial and biographical sketches of the defendants.

The selection of the defendants

The Socialist Workers Party was a major force within the American left. This was the product not only of its leadership of key strikes during the 1930s, but also, and above all, its identification with the political conceptions of Leon Trotsky. His enormous stature as leader, along with Vladimir Lenin, of the 1917 October Revolution; implacable opponent of the Stalinist degeneration of the Soviet Union; and one of the greatest writers of his time made Trotsky, even in exile, a major presence in world politics. Even after his assassination in August 1940, the lasting influence of Trotsky’s ideas was feared by his enemies among the Stalinists, the fascists and the “democratic” imperialists. First and foremost among those in the latter category was the US government under the leadership of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

There were two sets of defendants amongst the 29 charged: the party’s political leadership based in the SWP’s national headquarters in New York City, and the SWP’s representatives in Minneapolis, Minnesota who occupied positions of leadership in the region’s Teamster’s union, Local 544.

The first group of defendants consisted of long-standing leaders of the SWP, professional revolutionaries whose convictions were forged in the class struggles of the early 20th century.

Haverty-Stacke notes that foremost among these defendants was James P. Cannon, the national chairman of the SWP and the founder of Trotskyism in the United States. Born in 1890 in Rosedale, Kansas, Cannon read Trotsky’s critique of Stalinist policies while attending the Sixth Congress of the Communist International, held in Moscow in 1928. Upon returning to the United States, he declared his agreement with Trotsky. Expelled from the Communist Party, he founded the American section of the Left Opposition and established contact with Trotsky.

Felix Morrow, born in 1906 in New York City, was an SWP political committee member and revolutionary journalist who wrote for the party press. He was respected as the author of the book Revolution and Counter-Revolution in Spain. At trial, the prosecution emphasized Morrow’s position on the editorial board of Fourth International, the party’s theoretical journal.

Albert Goldman, another leading figure in the SWP, migrated to the United States from Belorussia at the age of seven in 1904. Goldman was best known for serving as Leon Trotsky’s attorney before the Dewey Commission of Inquiry’s hearings on the Stalinist show trials in 1937. The Roosevelt administration sought the indictment of these three men because their political and, in the case of Cannon and Goldman, personal association, was central to establishing, in accordance with the law, a conspiracy to overthrow the government. One significant omission from the list of defendants was Joseph Hansen, who served as Trotsky’s secretary for three years. It would seem logical for the government to have considered him the ideal defendant. His absence from the list will be discussed later.

The second group of defendants served in the SWP leadership in Minneapolis, where the party’s direction of the Teamsters union had established the Trotskyist movement as a significant political force commanding the respect of thousands of workers. Many of the Trotskyist defendants had personally led the victorious 1934 general truckers’ strike in the Twin Cities and fought to recruit 200,000 members to the union across the Midwestern states.

Haverty-Stacke describes the history of the Communist movement in the area, noting how Minneapolis became a center of support for the Left Opposition after the Stalinist Communist Party expelled the Trotskyists from the party in 1928: “Along with [Cannon] went other future Smith Act defendants in Minneapolis, including Vincent Dunne, Carl Skoglund, and Oscar Coover.” [1]

In the years following the general strike, the national Teamsters union under the leadership of close Roosevelt confidant Daniel Tobin unsuccessfully sought to purge Local 544 (and its predecessor, Local 574) of its Trotskyist leadership, employing the most vicious anti-communist propaganda.

In the weeks before the government initiated its prosecution, Local 544 was engaged in a renewed political battle over control of the Minneapolis Teamsters union. When Tobin and the Teamster leadership launched a new attempt to remove the Trotskyists from their positions, in part due to the SWP’s opposition to US entry into World War II, thousands of truck drivers voted to abandon the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and re-certify the local with the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO).

The Minneapolis defendants had played key roles in the decertification efforts. Vincent Dunne was one of them, and he was joined in the defendants’ dock by his brothers Miles and Grant. All three had led the general strike alongside Skoglund. Grant was unable to bear the immense pressure of the prosecution and took his own life on October 4.

Harry DeBoer, a truck driver, was active during the general strike and was shot by the police. A key member of the SWP in Minneapolis, he visited Trotsky in Mexico City several years later.

Grace Carlson was a social service worker and former professor at the University of Minnesota who ran as the party’s candidate for US Senate on an anti-war platform in 1940, garnering over 8,500 votes.

Jake Cooper, also from Minneapolis, served as Trotsky’s guard at Coyoacan for a four-month period in 1940.

Farrell Dobbs, a former coal yard worker, was appointed national labor secretary of the SWP in 1939 after organizing strikes of hundreds of thousands of truck drivers in the Midwest. Other Minneapolis-based defendants who were ultimately convicted included Max Geldman, Clarence Hamel, Emil Hansen, Carlos Hudson, Karl Kuehn, Edward Palmquist and Oscar Schoenfeld.

The editorial board of the party’s Fourth International magazine wrote in July 1941 after the indictment list was published: “Yes, there is a profound logic in the fact that these persecutions and prosecutions are instigated by the Gestapo-FBI at this time and in this place and against the specifically-designated victims.” [2]

This logic would play out at trial when the prosecution submitted evidence of the close connection several of the defendants had to Leon Trotsky in Mexico. The visits of Cooper, DeBoer, Vincent Dunne, Cannon and Dobbs to Mexico were presented as evidence of an anti-government conspiracy, as was Goldman’s close relation to Trotsky in the years preceding the trial. The government selected each “specifically-designated victim” with an eye to proving that a conspiratorial connection existed between Trotsky and the SWP’s alleged preparations for social revolution.

The Smith Act

The defendants were charged with two criminal counts. The first of the two charges against the 29 defendants was “unlawful conspiracy from and before July 18, 1938 to date of the indictment [June 23, 1941] … to destroy by force the government of the United States” in violation of 18 US Code Section 6, a Civil War-era statute written to suppress the slaveholders’ rebellion. [3]

The second charge alleged that those indicted “advised insubordination in the armed forces with intent and distributed literature to the same effect,” and “knowingly and willfully would, and they did, advocate, abet, advise and teach the duty, necessity, desirability and propriety of overthrowing and destroying the government of the United States by force and violence” in violation of the Alien Registration Act, also known as the “Smith Act” after the bill’s congressional sponsor, Howard Smith (Democrat of Virginia). [4]

Haverty-Stacke describes in detail the anti-communist predecessors to the Smith Act, from the criminal syndicate statutes of the “Red Scare”-era following World War I to the 1938 House Committee Investigating Un-American Activities, established by Texas Democratic Congressman Martin Dies.

The Smith Act’s criminal sedition sections made it a crime to advocate, write or organize for the overthrow of the US government, punishable by a jail term of up to 20 years. Its sections relating to immigration required the immediate registration of 5 million immigrants, 900,000 of whom were soon after categorized as “enemy aliens” subject to internment and/or immediate deportation. This same law used to target socialists and communists was also used to intern 120,000 Japanese-Americans on the West Coast during the war. In contrast to efforts to portray Roosevelt as a defender of democratic rights, he was at the very center of the intensification of repressive police measures.

The Communist Party, which took its political instructions from Moscow and the Soviet secret police, the GPU, wholeheartedly supported the Smith Act prosecution of the Trotskyists (as it later supported the internment of Japanese-Americans). CP leader Milton Howard supported the prosecution of the “fascist fifth column” on the grounds that the defendants “deserve no more support from labor and friends of national security than do the Nazis.” [5] Speaking in Minneapolis, Stalinist functionary Robert Minor said the Roosevelt administration should follow the example set by Moscow during the Great Terror of 1936-39 in dealing with the American Trotskyists. [6]

The passage of the Smith Act marked a drastic expansion of the surveillance powers of the state, aimed at socialist groups operating in the United States. Haverty-Stacke points out that in 1939, “three days before the House sent H.R. 5138, now known as the Alien Registration Bill, to the Senate, President Roosevelt issued a secret order ‘placing all domestic investigations [of espionage, counterespionage, and sabotage] under the FBI, Military Intelligence Division, and Office of Naval Intelligence,’ with the FBI as the central coordinating agency.” [7]

As early as 1936, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover was sending Roosevelt reports on “domestic subversives,” which included the Trotskyist leadership. [8] Hoover continued to pressure the president for the authority to intensify his surveillance, and Roosevelt signed the bill into law on June 29, 1940. Haverty-Stacke writes that by the time the bill became law, the FBI’s infiltration of the SWP was already well underway: “By late 1939, both Teamsters Local 544 in Minneapolis and the Socialist Workers Party headquartered in New York became targets of the bureau’s investigations.” [9]

The decision to prosecute

As the US prepared actively for entry into the war, Roosevelt faced the challenge of imposing the type of class discipline needed for the war effort. For the previous 22 months, the Stalinist Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA) had opposed US involvement in the war in Europe, in keeping with the August 1939 Stalin-Hitler pact. But with the German invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, the CPUSA pivoted from opposition to US intervention in the war to full support for the Roosevelt administration’s war drive. The Stalinists immediately began transforming their apparatus into a mechanism to police the working class and enforce a nationwide “no strike” policy.

The Roosevelt administration decided to prosecute the Trotskyists on June 23, 1941, the day after the German invasion of the Soviet Union. With the CPUSA reversing its previous stance to become a pro-war party, the SWP became the most significant socialist anti-war party in the United States. The Roosevelt administration was concerned that the movement’s principled opposition to imperialist war would make it a pole of attraction for anti-war sentiment in the American working class.

The decision to prosecute followed months of intense discussion at the highest levels of the Department of Justice and the FBI. Haverty-Stacke examines the contentious legal and political problems that confronted the government.

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover

Hoover was an early advocate of prosecution. But for the Department of Justice and Roosevelt himself, prosecution entailed a series of risks. Leading administration officials such as Department of Justice lawyer Francis Biddle were concerned that the prosecution could generate broad opposition, galvanizing the SWP and alienating the Roosevelt administration’s liberal base.

In June 1941, Hoover attempted to pressure Roosevelt, claiming that should the US enter the war, the Socialist Workers Party could “cause a tie-up of materials flowing to and from plants in that vicinity having National Defense contracts.” [10] That same month, US Attorneys Victor Anderson and Wendell Berge indicated their support for prosecution. [11] On June 12, Teamsters President Tobin sent Roosevelt a telegram requesting prosecution. Haverty-Stacke writes: “Tobin argued that the Trotskyists, who had succeeded in organizing drivers across the central states, were in a position to disrupt the nation’s commercial transportation networks, and, if they took advantage of the war crisis, could overthrow the government and set up a socialist state.” [12]

The SWP claimed during the trial and in its aftermath that Roosevelt decided to prosecute the SWP as a result of Tobin’s June 12 telegram. But this was only partially true. Haverty-Stacke explains:

“Because of this telegram, Tobin has been accused of setting in motion the chain of events that led to the arrest of twenty-nine members of the SWP and Local 544. At the time of those arrests and during the trial, the defense argued that Tobin called in a political favor from Roosevelt and that the president intervened in an internal union dispute, launching the first Smith Act prosecution. This ‘political debt’ argument has survived in varying degrees in the limited scholarly literature on the case and has informed the popular memory of the prosecution within the SWP. The Department of Justice, however, had already been seriously considering such prosecution as early as April 1941, based on the independent investigation of the FBI dating back to the fall of 1940.” [13] (Emphasis added)

Ultimately, according to Haverty-Stacke, Francis Biddle “made the move in this case largely because of the intelligence he received from the FBI.” [14]

The centrality of Leon Trotsky to the prosecution’s case

Though Haverty-Stacke does not focus on this issue in her book, the WSWS’ investigation of the trial record makes clear that the prosecution’s theory of the case is centered on establishing the connection between the SWP defendants and Leon Trotsky. This became the crucial legal issue around which the entire case revolved. Under this theory, Trotsky was the architect, instructor and director of the SWP’s activities in Minneapolis and across the country. So central was Trotsky to the prosecution’s case that he was listed as a co-conspirator at the grand jury phase, despite the fact that he had been killed the prior August.

The experienced US attorneys from the Department of Justice, aware that a verdict of “not guilty” on both counts would be an immense embarrassment for the administration, laid out a strategy aimed at securing convictions. Their theory of the case revolved around showing the connection between Trotsky and the SWP defendants.

The prosecutors searched for any evidence that tended to show the defendants had met or corresponded with Trotsky or traveled to Mexico City. They submitted evidence of even the slightest connections between the SWP and Trotsky to advance their theory.

In the prosecution’s opening argument, the US attorneys claimed that the SWP:

… was an instrumentality framed by a man who departed this life in August 1940, by the name of Leon Trotsky, who at the time of his departure, I believe, was in exile in the Republic of Mexico, and that this party was the Trotsky Party, or the party was dedicated to carry into effect the ideas and the plans and the views of Leon Trotsky with respect to the establishment of a government here on earth, and particularly as this refers to the United States of America, and that the program of this party, or the ideas that were basic in this party, represented the views of Leon Trotsky, and those of his contemporary, the first executive head of the Soviet Union, V.I. Lenin, and that their philosophy was that they could reach a solution of all their problems by the establishment of a workers’ state… and that the defendants, or a large number of them, with the knowledge of all these defendants here on trial, made trips to Leon Trotsky in Mexico for the purpose of receiving his counsel and guidance and direction from time to time, not only in furnishing a personal bodyguard and in furnishing protection to Leon Trotsky, for his personal safety, but otherwise contributing to Leon Trotsky and his activities while he was at the outskirts of Mexico City, in Mexico, until the time of his assassination, and that these ideas of Leon Trotsky’s are the ideas of the Socialist Workers Party, and so far as the evidence in this case will show, the affirmative and positive ideas of all the defendants upon trial. [15]

Even a single visit to Trotsky in Coyoacan was flaunted by the prosecutors as proof of conspiracy. So brazen were the state prosecutors that SWP attorney and defendant Albert Goldman raised legal objections to the prosecution’s excessive reliance on evidence of SWP visits to Mexico. The government, Goldman claimed, made it seem that visiting Trotsky was itself a conspiratorial act. US Attorney Schweinhaut replied:

The law, I am certain, as counsel knows, with respect to a conspiracy, is that a conspiracy can be accomplished not alone by doing an illegal act but by the doing of, for example, legal acts for an unlawful purpose. The testimony here has already shown and it will be shown again that these men held out Trotsky as their leader. It becomes an important matter to show the association of the defendants personally with Trotsky and in doing so it can be shown what the nature of the association was. [16]

In particular, the prosecution sought to show that Trotsky elaborated two of the SWP’s “conspiratorial” policies—the SWP’s proletarian military policy and the Union Defense Guard.

The proletarian military policy was developed by Trotsky and communicated to the SWP leadership through personal meetings and extensive correspondence in the years that preceded Trotsky’s assassination in August 1940. [17] The proposal for a Union Defense Guard was initiated by Trotsky for the purposes of defending workers and socialists from attacks by fascist paramilitary organizations, which had established a presence in Minneapolis.

The prosecution’s theory of the case relied on showing (a) that such programs existed and were being implemented by the SWP in Minneapolis, (b) that they were conceived of by Trotsky, and (c) that Trotsky’s suggestions were conveyed to the SWP via personal communication with several of the defendants. The US attorneys spent five weeks at trial using evidence gathered through months of investigation to prove each link.

The previously unknown extent of government infiltration of the SWP

Haverty-Stacke’s book reveals that by late 1940, the FBI had acquired extensive knowledge of the SWP’s activities and had access to high-level informants within the party’s New York headquarters.

The surveillance of the Trotskyist movement had begun in the mid-1930s, when the FBI began placing certain party leaders under surveillance. Haverty-Stacke notes: “The Trotskyists found themselves targets of both the SDU’s [Special Defense Unit’s] recommendations and the FBI’s Custodial Detention list. A few of the ‘18’ had already been categorized by Hoover in the most dangerous grouping—‘A1’—before their prosecution.” [18]

By late 1939, as Haverty-Stacke notes, the FBI had already targeted the SWP in Minneapolis and New York. But even the following year the infiltration was still somewhat primitive. In April 1940, the FBI resorted to paying a janitor at a Chicago event center to retrieve information from trashcans regarding delegates to the SWP congress.

In this period, Haverty-Stacke explains, there were two essential elements to the government infiltration. First, the government obtained informants from a minority faction of Local 544 that was opposed to the Trotskyist leadership on an anti-communist basis. James Bartlett, the government’s star witness at trial, represented this reactionary element. Second, the government based its infiltration program on the acquisition of informants from within the SWP.

According to Haverty-Stacke, the FBI sought to recruit agents from within the SWP leadership. They attempted to contact and recruit SWP leaders in the months before the Roosevelt administration made the decision to prosecute.

According to the testimony of FBI informant Henry Harris, FBI Agent Perrin asked Harris to convey an offer to SWP defendant Carl Skoglund in early 1941. [19] Skoglund, a Swedish-born socialist, was living in the US without proper immigration papers. The FBI offer was for Skoglund to provide information to the FBI in return for impunity and a permanent resolution of his immigration problems. Skoglund refused the offer. A central element of the FBI’s infiltration was offering key figures an “impunity” incentive to become informants and aid the prosecution. [20]

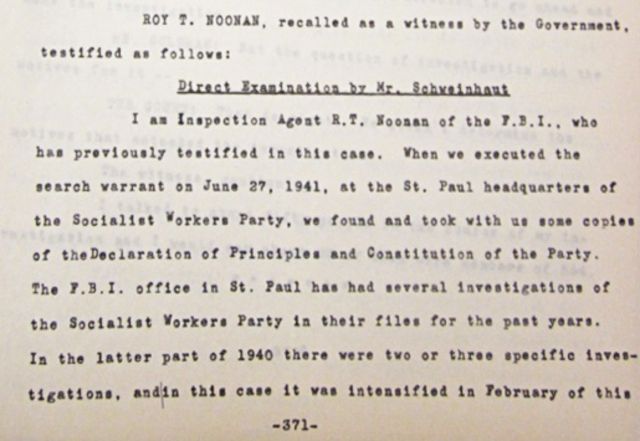

FBI Agent Roy Noonan testified that the FBI obtained a major new source of information in the autumn of 1940. Noonan played the role of lead investigator, tasked with overseeing the evidence-gathering operation against the SWP in Minnesota.

US Attorney Henry Albert Schweinhaut and SWP Attorney Albert Goldman questioned Agent Noonan. Noonan noted that by 1941, the FBI “had several investigations of the Socialist Workers Party in their files for the past years.” [21]

Schweinhaut asked Noonan when the FBI began its investigation into the SWP defendants and Noonan replied: “[W]e have had several of them in our files in past years, but in the latter part of 1940, two or three specifically.” [22] (Emphasis added)

On cross-examination, Goldman and Noonan had the following exchange:

Goldman: And how long before that did the investigation start, as far as you know?

Noonan: I know that the investigation was being conducted in February and March [1941], and I know that we have had information regarding some of the defendants long before that.

G: How long before that?

N: I know we had it in November, 1940. [23]

The November 1940 date corresponds with Haverty-Stacke’s finding that the decision to prosecute was “based on the independent investigation of the FBI dating back to the fall of 1940.” [24]

After the FBI obtained a higher degree of information regarding the defendants in November 1940, the FBI was able to oversee a vast expansion of its infiltration network. Noonan testified at trial that the surveillance “was intensified in February and March of this year [1941].” [25]

Recently declassified FBI communications show a qualitative development in the FBI’s infiltration network from November 1940 to mid-1941. The FBI files include dozens of reports by agents located in Omaha, Kansas City, St. Louis, Minneapolis, Seattle, Los Angeles, Mississippi, New York, New Jersey and elsewhere, quoting from confidential informants. The FBI files from the year 1941 include transcripts of branch meetings and full subscription lists to the party press. The FBI knew how much money each branch was raising and when it was holding meetings. The FBI had full schedules of the national speaking tours before they were publicly announced, as well as minutes from Political Committee meetings. It was aware of who was elected to serve on what national board, including the Control Commission. The FBI had also acquired substantial information about foreign affiliates to the Fourth International, indicating a high degree of infiltration of the New York headquarters.

“By the spring of 1941,” Haverty-Stacke writes, “the investigation thus had broadened out beyond the Teamsters in Minneapolis to mesh with the existing investigations of national SWP leaders in New York.” By that time, the party’s “two most active branches [Minneapolis and New York] remained under heavy FBI surveillance, riddled with well-placed informants.” [26] (Emphasis added). According to Haverty-Stacke, “The FBI watched the SWP’s national headquarters in New York in particular very closely.” [27]

Hoover’s priority at trial: Preventing the exposure of the SWP informant network

Internal government documents uncovered by Haverty-Stacke also shed light on the qualities Hoover was looking for in an informant. Haverty-Stacke points to a June 1941 conversation between Hoover, leading Department of Justice lawyer Francis Biddle and US Attorneys Schweinhaut and Berge. In the course of this discussion, the Department of Justice lawyers suggested the FBI place its own agents in SWP headquarters in New York to gather evidence in preparation for trial.

Schweinhaut was first to propose this plan of action to Hoover. Berge seconded Schweinhaut, writing Hoover in mid-June 1941: “If you think there is information which, from the investigative standpoint, can be best secured by the method you discussed with me on the telephone, you are authorized to order such an investigation,” noting that the administration attorneys “agree that it would not amount to entrapment so long as the government agents do not inspire the doing of illegal acts merely for the purpose of getting evidence.” [28]

Hoover’s response revealingly sheds light on his strategy for infiltrating the SWP. His concerns were two-fold.

Replying to the Justice Department attorneys, he first expressed a fear that FBI agents placed in headquarters for the purpose of gathering evidence for trial could pose a “serious possibility of embarrassment to the Bureau … if the agent were later used as a witness and required to testify in open court.” [29]

In an additional section of his response letter (a section to which Haverty-Stacke does not make reference), Hoover explains that not only was the Justice Department suggestion risky, it would also be ineffective from an information gathering standpoint.

Hoover wrote: “The possibilities of obtaining important evidence in the immediate future through such an arrangement are very doubtful, inasmuch as a new member of the Party would necessarily have to establish himself and satisfy the Party leaders as to his reliability prior to being the recipient of confidential information,” and that this would take a “considerable amount of time, probably months.” [30]

From these quotations, the following conclusion can be inferred. To Hoover, an informant was valuable insofar as he (a) could be protected from being exposed publicly by testifying at trial, (b) was already operating at the highest levels of the SWP and with the confidence of the SWP leadership, and (c) could provide the FBI with information immediately without the risks and delays associated with an outside agent ingratiating himself into the party leadership.

This discussion took place in mid-June 1941. Eight months earlier, Hoover had begun personally monitoring discussions between B.E. Sackett, the FBI’s chief agent in New York City, and Joseph Hansen, a key leader of the SWP who had served as Trotsky’s secretary in Mexico City.

Hansen met all of Hoover’s criteria. He had already won the confidence of the party leadership and was in a position to provide “important evidence” to the FBI without delay and with minimal risk of exposure. As the prosecution unfolded over the following months, Hansen’s name was almost inexplicably absent from the list of SWP defendants.

To be continued.

**

Notes:

[1] Haverty-Stacke, Donna T. Trotskyists on Trial: Free Speech and Political Persecution since the Age of FDR. (New York, New York: New York UP, 2016), Print. p. 77. FDR. (New York, New York: New York UP, 2016), Print. p. 11.

[2] The Editors, ed. “The FBI-Gestapo Attack on the Socialist Workers Party,” Fourth International 2.6 (1941): 163-66. Marxists.org.

[3] Haverty-Stacke at 77.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Id. at 79.

[6] Id. at 108.

[7] Id. at 34. (Citing “Confidential Memo for the Secretary of State, the Secretary of the Treasury, the Secretary of War, the Attorney General, the Postmaster General, the Secretary of the Navy and the Secretary of Commerce from President Roosevelt, June 26, 1939, OF 10b, box10, FDRPL”).

[8] Id. at 41.

[9] Id. at 30.

[10] Id. at 62.

[11] Id. at 61.

[12] Id. at 60.

[13] Id. at 61.

[14] Id. at 73.

[15] Prosecution’s Opening Statement, US v. Dunne et al., 26-27.

[16] Testimony of James Bartlett, US v. Dunne et al., 130.

[17] For a detailed explanation of the character of the proletarian military policy, see The Heritage We Defend, Ch. 6: “Trotsky’s Proletarian Military Policy,” accessible here. Also available at Mehring Books.

[18] Haverty-Stacke at 153. (Citing J. Edgar Hoover to Special Agent in Charge, New York, June 16, 1942, re. Farrell Dobbs, Internal Security, in Farrell Dobbs’s FBI file 100-21226, FOIA, in the author’s possession; Joseph Prendergast, Acting Chief SDU, to Wendell Berge, January 31, 1942, and Wendell Berge to J. Edgar Hoover, April 25, 1942 in Farrell Dobbs’s FBI file 146-7-1355, FOIA, in the author’s possession; Chief of SDU to J. Edgar Hoover, February 26, 1942, in Dunne’s FBI file 100-18341, and Edward Palmquist’s Custodial Detention Card, in Palmquist’s FBI file 146-7-1213; J. Edgar Hoover to Chief of SDU, March 31, 1941, in Dunne’s FBI file 100-18341).

[19] Testimony of Henry Harris, US v. Dunne et al., 507.

[20] Id. at 78.

[21] Cross Examination of Agent Roy T. Noonan, US v. Dunne et al., 371.

[22] Id. at 372.

[23] Id. at 371.

[24] Haverty-Stacke at 61.

[25] Id. at 371-372.

[26] Haverty-Stacke at 155.

[27] Id. at 154. (Citing FBI report 100-413, NYC 10/20/42 and 12/3/42, f. 7, box 108, SWP 146-1-10).

[28] Id. at 63. (Citing J. Edgar Hoover to Matthew McGuire, June 25, 1941, f. 2, box 108, SWP 146-1-10; Wendell Burge to Henry Schweinhaut, June 25, 1941, f. 2, box 108, SWP 146-1-10; J. Edgar Hoover to Matthew McGuire, June 25, 1941, f. 2, box 108, SWP 146-1-10).

[29] Ibid.

[30] J. Edgar Hoover to Matthew McGuire, June 25, 1941, f. 2, box 108, SWP 146-1-10.

Follow the WSWS