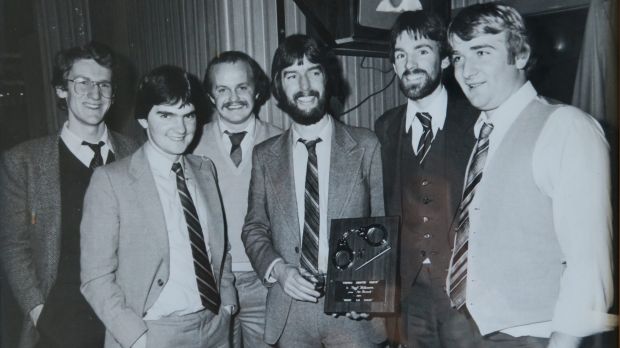

The day I walked into the pressrooms at the Russell Street Police Station was the first time I felt I might actually have some sort of a future in the journalism caper.

This, however, was a not a view shared by my brand new colleagues. The Sun's chief police reporter of the day, Geoff Wilkinson, would say much later, "You were a cocky, arrogant smart arse who thought you knew everything".

I was shocked at this revelation as humility is virtually my middle name (actually it is Leslie but you get the drift).

Certainly in those early days as a cadet reporter I had no reason to be cocky as I was spectacularly inept and my only knowledge of newspapers came from watching reruns of All The President's Men.

In the end, the chief of staff sent me to police rounds, probably to get me out of his sight, but for me it was a new beginning. The office smelled, there were old typewriters, files back to the 1940s and a set of characters that seemed out of The Front Page. I loved it.

There was the nightshift guy, Graeme "Charlie" Walker, who appeared to be part bear and part werewolf, Peter William Robinson, who had a habit of ringing the main office after midnight describing the exact method he would use to murder the sub-editor who changed his copy and "Big" Jim Tennison who took to driving the office car down disused railway tracks to avoid being breathalysed on busier thoroughfares.

Wilkie sat in a little cubicle on a green canvas chair, chasing yarns and guiding his team of reporters with their stories, never muscling in, pulling rank or whacking his name on someone else's story. Today he would be called a mentor. Back then he was simply "The Boss".

We had a police scanner and listened for calls to serious crimes such as a 69 (homicide), 79 (shooting) or 19 (police in trouble). I was baffled when Wilkie would mutter numbers into the phone in what appeared a random fashion until I was told they were his quadrella bets, a ritual he took nearly as seriously as chasing yarns.

Our paths to police rounds were poles apart. I floated into journalism on a whim and fluked a job. He had been knocked back more than once but refused to give up.

He took an administrative role at the Herald and Weekly Times in the hope it would lead to the reporters' room but when he was given a dustcoat he realised it led to the mailroom.

Finally he scored a job with the brand new and short-lived afternoon paper Newsday as a sports reporter and when it folded, with the Hobart Mercury, in 1973 he joined The Sun News Pictorial and within weeks moved to police rounds.

For some years now Geoff has battled Parkinson's disease. The disease has increasingly intruded on his quality of life until he recently underwent deep brain stimulation with extraordinary results. More of that later.

Back in the late 1970s The Sun was a police rounds paper and we felt that when we weren't on page one it was a calculated insult. (The exception was a Laurie Oakes budget leak that even we acknowledged deserved the front page).

Many of the stories were straightforward cops and robbers yarns but organised crime – particularly drugs and its permanent partner, corruption – was taking hold.

As crime changed, so did police reporting. It became deadline-driven investigative journalism while the "Hounds at the Round" were still expected to sniff out daily scoops.

This is when Wilkie came into his own.

In May 1979 two bodies, those of Isabel and Douglas Wilson, were discovered dumped in Rye – a huge story that was more than a murder mystery. Soon Wilkie discovered they were drug couriers for an international syndicate looking to escape a business where redundancy packages are often delivered by paid hitmen.

His page one was a bombshell. He revealed the couriers were secret police informers and were murdered because corrupt investigators from the Federal Narcotics Bureau leaked to the gang's leaders.

Predictably the federal government denied the story although Geoff followed up with another page one. Eventually a Royal Commission found Wilkinson was right – the bureau was hopelessly corrupt and was disbanded.

In 1981 he left The Sun to become media director for chief commissioner Mick Miller until 1989, where he built a reputation for honesty with reporters and volcanic dummy spits if he felt the force was unfairly maligned.

It was at a police function at the Airlie Officers' College that he noticed his right hand shaking – so much so he had to switch his soup spoon to his left. "It was embarrassing more than anything," he said.

He went to a neurologist who suggested it was brought on by stress and specifically ruled out Parkinson's. So he just got on with life, winning a Churchill Fellowship and coming back with an idea of encouraging the public to "Put the finger on crime". And so 30 years ago Crime Stoppers was born. In 2008 he was awarded a Medal of the Order of Australia for the initiative.

This week Crime Stoppers released record annual results in Victoria with 1541 arrests, 5599 charges and seizures of $7.1 million of drugs and $1.8 million in property.

In 1989 he returned to mainstream journalism, firstly with Channel Nine and then in 1994 with the Herald Sun as a specialist crime reporter.

The tremor worsened, although in 2002 a neurologist assured him he was still clear. Yet there were other signs that in hindsight showed his condition was progressing to something more serious. "About 15 years ago I gradually lost my sense of smell. Now I know that is a symptom of Parkinson's."

We thought it was a blessing as on police rounds fishing trips he was billeted to share a room with a former colleague who appeared to live on a diet of fruit cake, blue cheese and bourbon. When the door was opened in the morning you would be forgiven for believing a warthog had died under a bunk.

In 2007 while receiving a routine flu shot at work the doctor noticed Geoff struggling to rebutton his shirt and suggested a specialist appointment. At the subsequent consultation it took the neurologist 60 seconds to diagnose Parkinson's; a disease that was "chronic, progressive and incurable".

He was told there were drugs to control the symptoms that would give him a "honeymoon period" of five years with the doctor advising if he had any ambitions requiring independent mobility he should "get on with them".

Over the years Geoff, now 66, has been known to have the occasional whinge. Such matters as garlic in his pasta, being given out when he didn't edge the ball, even though he was caught at second slip, a story that failed to make page one or, worst of all, losing the last leg of the quaddie, were matters that would result in a bout of moaning.

But when delivered this life-altering diagnosis he remained remarkably stoic, returning to work where most of his colleagues were unaware of his battles. We would catch up regularly and he seemed the same old Geoff, just a little thinner and a little quieter.

His wonderful wife, Dorothy, said we didn't see the worst because the dinners coincided with the times when his medication was suppressing the symptoms.

He was given the lifetime achievement award by the Melbourne Press Club in 2010. He retired in 2012 but was snapped up by the Sentencing Advisory Council and the Adult Parole Board where his decades of dealing with victims could be used to advantage.

To get to the Parole Board at 8.30am required him to be out of bed by 5am. "The most frustrating element of the disease is how simple things take so long." He was taking seven pills a day, the shakes were getting worse and his voice thinner. At functions he would drift off and we feared we were losing him.

Then his new neurologist suggested he look at deep brain stimulation where the patient remains awake as holes are drilled in the skull and wires implanted in the brain. (The patient is kept awake because the surgical team need feedback to ensure the probes are perfectly placed. It is a little like twisting an old-fashioned rabbit ear antenna until you pick up SBS – or in Wilkie's case the Racing Channel.)

A pacemaker-type device is planted in the chest to send signals to the electrodes in the brain to suppress Parkinson's symptoms. On August 30, under neurosurgeon Kristian Bullus and neurologist Wesley Thevathasan, he went under the knife, or more accurately the drill.

While it is not a cure the early results seem astounding. The quaver in his voice has disappeared and he sounds 15 years younger. He is off medication, the shakes are gone and for the first time in years he is sleeping eight hours a night.

And in recent weeks he has gained three kilograms, as his body is no longer burning energy while at war with itself. "Dorothy says I have my sense of humour back but I didn't think I ever lost it."

While the gizmo in his chest is still being tweaked and remains a work in progress Wilkie said his improvements have exceeded his best hopes.

"They say it can provide relief for more than 10 years and that will do me for starters."