Art Is Our Last Hope

by Tatiane SchilaroEnglish is not my mother tongue. I arrived at the American field of art criticism like an alien arrives in an idealized land with a sole piece of luggage. I had to invent familiarity with spoken, written, and seen repertoires at the same time that I had to write at ease, as if I were sitting at home on my cozy sofa, so that readers could engage with my language. There were times that my writing was formless: it was as if I was writing in Portuguese while using English. That still happens, but the process of raising the wave of the “foreign” language has changed because I rooted my writing in the imagined realities I created about art: “fables” about artworks and images, which were always there to rescue me when I would start drowning amidst semantic waves.

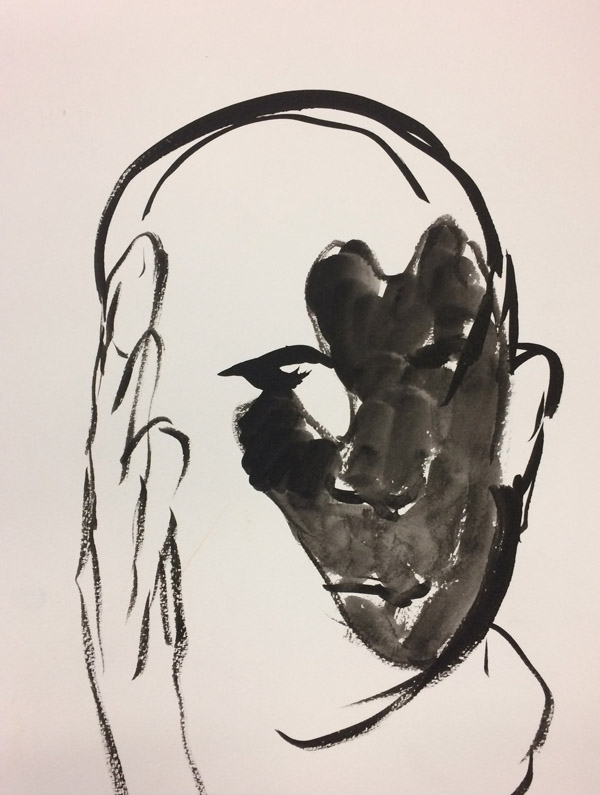

Maya Grace Strauss, Portrait of Leon Golub (based on a photograph by David Reynolds), 2016. Ink on paper.

Maya Grace Strauss, Portrait of Leon Golub (based on a photograph by David Reynolds), 2016. Ink on paper.Conceptual artist Paulo Bruscky, very active during the military dictatorship in Brazil (1964 – 84) once said that “art is our last hope.” He believed that art could break with normative realities, such as the one installed by the dictatorship. He was right: art can still break with today’s anxiety for the Real that comes detached from criticality. It is in that sphere that the art critic becomes a political body, a bond between art and reality. She weaves words into images, flesh, and meaning, knitting a space of dialogue through her own and the artist’s breaths, through how art bounces off her body and connects with her memory of things seen, and yet to be seen. It is in the space of a reality that has yet to come that art criticism becomes not only an affective exercise, but also an alternative to the coerciveness of global capitalist projects: the constant making and remaking of the Real.

This September, I traveled to Brazil to see the 32nd São Paulo Bienal. I noticed that local critics were disappointed by what they called a “politically correct” Bienal, whose works lacked the formal qualities of “true art.” As a Brazilian living abroad, my understanding of the exhibition was the inverse: even though the Bienal was only a partial decolonizing exercise, in its current political context, what critics called “politically correct” was in fact the affirmation of spaces of difference in which works produced by Afro-Brazilians and indigenous peoples were at the forefront.

While the recent impeachment of Dilma Rousseff served as a move to staunch the financial crisis that ravaged the middle and lower classes in Brazil, it also opened a dangerous space for the legitimization of intolerance against minorities propelled by the elite. Some of the works in the Bienal—against that move—insistently reminded visitors of the social domains that the new government now seeks to pacify or erase. But local critics were not interested in engaging with those political and social dimensions; instead, they chose the “off with their heads” style that became a disservice to the art and to those minorities represented through it. That division shows that, despite the so-called crisis of criticism, and no matter the language one writes in, art criticism and writing, as political fabulations, are essential instruments that should be intensively deployed in the battles against the bigotry of our times. Starting now.

Contributor

Tatiane SchilaroTATIANE SCHILARO is a Brazilian-born art writer and a Ph.D. student in Visual Studies at the University of California Santa Cruz. She graduated in 2015 from the Art Criticism and Writing Master’s Program at the School of Visual Arts, and has an MA in Art History, Contemporary Art. In 2015, she coauthored the book Contemporary Art in Brazil (Edições Pinakotheke, Rio de Janeiro). Her essays and reviews have been published by Guernica, ARTNews, Artcritical, Hyperallergic, and NewCityBrazil. She was a curatorial intern at El Museo del Barrio, the Museum of Modern Art, and at the Whitney Museum of American Art.