Unemployment: Don't be fooled by the headlines, new numbers expose weak state of jobs market

Updated

Taylor Smith is a 32-year-old mother with a young child from Mount Kiara in NSW. She has a job so isn't recorded in the 5.6 per cent of Australians who are officially unemployed.

She is an example of how the unemployment figure is masking what's really going on.

In fact, she has two jobs. But together those two jobs give her just 16 hours a week, much less than she would like to work and leaving her struggling to make end's meet. She is what economists call underemployed.

"I have one job at the supermarket, I have another job, a casual job which I get very little hours from and [my partner] has two-part time jobs so we definitely feel we're underemployed," she told ABC News.

Taylor's story is in stark contrast to the official figures out today, and much of the spin surrounding them.

According to today's ABS data, Australia's official unemployment rate has held steady at 5.6 per cent - a fall of 0.4 per cent over the past year.

It's a result the Government has trumpeted as a ringing endorsement of the strength of the Australian economy. But scratch beneath the surface and you see how misleading the headline numbers are.

Anaemic growth

Jobs growth over the past 12 months has been anaemic. Employment has increased by just 0.9 per cent, which is half the average we've seen over the last 20 years.

In fact, this month was particularly bad for jobs growth. Trend employment decreased between September and October, the first decrease since 2013.

Things are going backwards.

The reason we haven't seen a spike in unemployment is because an increasing proportion of the population has given up looking for work.

The participation rate has dropped 0.6 per cent over the last year. Increasing numbers of people aren't being classified as unemployed because they've become so disillusioned that they've stopped looking.

The other factor disguising the weak state of the jobs market is the increasing casualisation of the workforce.

Commonwealth Bank economist Gareth Aird said the labour market is in much worse shape than the headline figures would suggest.

"We've got record high underemployment. Which means the percentage of people who are working but would like to work more hours is very high. We've got falling participation, we've got record low wages growth and we've also got hours per head coming down."

If this truly was a tightening labour market, we could expect workers to be able to bargain for high wages.

Instead, we have wage growth of just 1.9 per cent per year, the lowest rate since the current series began two decades ago and, on some estimates, the lowest wages growth for more than 50 years.

RBA doesn't have data on labour market 'slack'

The economists at the Reserve Bank are heavily data driven. The problem is, as they admitted in their most recent board meeting minutes, when it comes to the labour market they don't have the data they need.

"Members noted that the degree of spare capacity in the labour market depended on how many additional hours workers were seeking and that relevant data were not readily available," they said.

They don't know how many extra hours people like Taylor and her partner want to work, so they don't know how much 'slack' there is in the labour market.

Not having access to that data is becoming an increasingly large problem because there's a lot more part-time workers than there used to be. Between December 2015 and October (the most recent figures) full time employment fell by 69,900 people.

But part-time employment increased by 132,700 people over the same period. The jobs that are being created are increasingly part-time and casual and a lack of security makes it harder for workers to bargain for higher wages.

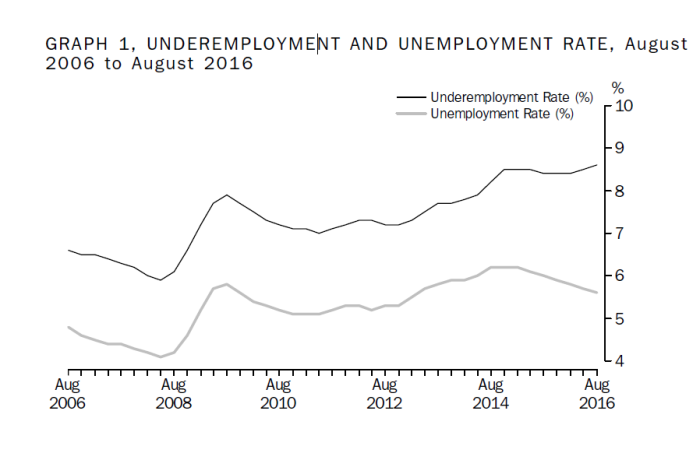

When the level of unemployment falls, then so does underemployment. But in the last couple of years, this relationship has broken.

Unemployment has fallen, but the percentage of people who would like to work more has gone up.

Photo:

When the level of unemployment falls, then so does under-employment, but this has changed in the last few years. (Source: ABS)

Photo:

When the level of unemployment falls, then so does under-employment, but this has changed in the last few years. (Source: ABS)

There is an argument that Australia's low unemployment rate is a testament that flexibility in the labour market is working.

Instead of laying off workers, employers are making roles part-time or offering lower wage rises. But low wage growth and a lack of job security is still a handbrake on the economy.

If workers have less cash in their pockets or don't feel secure in their jobs then they're less likely to spend, which stifles economic growth.

Low unemployment has traditionally been the most important economic badge of honour a government can wear.

But if it's being driven by well paid, full-time jobs being replaced by poorer paid part-time jobs and people being driven out of searching for jobs by despair, then it's not one that should be worn with pride.

Topics: economic-trends, business-economics-and-finance, money-and-monetary-policy, australia

First posted