Chinese–U.S. relations (or

Sino-American relations) refers to

international relations between the

United States of America (U.S.A.) and the

People's Republic of China (P.R.C.) Most analysts characterize present Chinese-American relations as being complex and multifaceted. The United States and China are usually neither allies nor enemies; the U.S. government does not regard China as an adversary but as a competitor in some areas and a partner in others.

The

Qing Dynasty opened the first modern official diplomatic relations in late 19th century, After

Xinhai revolution, newly formed

Republic of China maintained diplomatic ties with the USA. During the

Second World War, China was a close ally of the United States. At the founding of the communist-ruled

People's Republic of China in 1949, the USA did not immediately recognize the newly established government of China. Until January 1979, the United States recognized the Republic of China on

Taiwan as the legitimate government of China, and did not maintain diplomatic relations with the People's Republic of China on the mainland. In the midst of the

Cold War, the

Sino-Soviet split provided an opening for the US to establish ties with mainland China and use it as a counter to the

Soviet Union and its influence. It was after January 1979 that the USA government switched recognition from

Taipei to

Beijing, as well as the diplomatic relations.

As of 2011, the United States has the world's largest economy and China the second largest. China has the world's largest population and the United States has the third largest after India. The two countries are the two largest consumers of motor vehicles and oil, and the two greatest emitters of greenhouse gases.

Relations between China and the United States have been generally stable with some periods of tension, most notably after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, which removed a common enemy and ushered in a world characterized by American dominance. There are also concerns relating to human rights in the People's Republic of China and the political status of Taiwan. There are constant tides and strides in the Sino-U.S. relations, and diplomatic efforts were taken to maintain the positive direction in this international relationship, such as James R. Lilley around 1990's.

While there are some tensions in American-Chinese relations, there are also many stabilizing factors. The PRC and the United States are major trade partners and have common interests in the prevention and suppression of terrorism and nuclear proliferation. The U.S.-China trade relationship is the second largest in the world.

China is also the largest foreign creditor for the United States. China's challenges and difficulties are mainly internal, and there is a desire to maintain stable relations with the United States. The American-Chinese relationship has been described by top leaders and academics as the world's most important bilateral relationship of the 21st century. As the countries become more and more intertwined, greater numbers of Chinese and Americans have experience visiting, studying, working, and living in the others' country. Still, the role played by the media in shaping views remains large. In recent years, public opinion polling and other scholarship has sharpened our understanding of how images and attitudes in the two countries are formed and how those influence policies.

Country comparison

| !

|

China>People's Republic of China

|

United States>United States of America

|

|

|

|

1,347,350,000 (1st) (19.1% of the world population)

|

314,256,000 (3rd) (4.46% of the world population)

|

|

9,572,900 km2 (3rd)

|

9,526,468 km2 (4th)

|

|

139.6/km² (363.3/sq mi)

|

33.7/km² (87.4/sq mi)

|

|

Běijīng

|

Washington, D.C.

|

| Largest City

|

Shànghǎi – 23,019,148 (2010)

|

|

| Government

|

|

Federalism |

| First Leader

|

[[Máo Zédōng

|

George Washington

|

| Current Leader

|

Xí Jìnpíng

|

Barack Obama

|

| Official languages

|

Standard Chinese

|

|

| Main religions

|

42% Agnostic or atheist, 30% Folk religions and Taoism, 18% Buddhism, 4% Islam, 4% Ethnic minorities indigenous religions (including Vajrayana and Theravada), 2% Christianity |

|

| Ethnic groups

|

91.51% Han Chinese, 55 recognised minorities, 1.30% Zhuang, 0.86% Manchu, 0.79% Uyghur, 0.79% Hui, 0.72% Miao, 0.65% Yi, 0.62% Tujia, 0.47% Mongol, 0.44% Tibetan, 0.26% Buyei, 0.15% Korean, 1.05% other (See List of ethnic groups in China) |

74% White American, 14.8% Hispanic and Latino Americans (of any race), 13.4% African American, 6.5% Some other race, 4.4% Asian American, 2.0% Two or more races, 0.68% American Indian or Alaska Native, 0.14% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander |

|

medium) (89th)

|

0.910 (very high) (4th)

|

| Currency

|

|

[[United States dollar">United States dollar |

$15.094 trillion (1st)

|

|

$5,413 (90th)

|

$48,386 (15th)

|

|

$11.299 trillion (2nd)

|

$15.094 trillion (1st)

|

|

$8,382 (91st)

|

$48,386 (6th)

|

|

47.4

|

|

|

0.663 (medium) (89th)

|

0.910 (very high) (4th)

|

| Currency

|

|

[[United States dollar ($)

|

| Chinese Americans

|

|

|

|

$143.0 billion

|

$711.0 billion

|

|

4,585,000 (about 1 military or paramilitary personnel per 294 persons)

|

3,000,000 (about 1 military or paramilitary personnel per 105 persons)

|

|

10,000,000 (0.74% of the total population)

|

267,444,149 (85.1% of the total population)

|

|

780,000,000

|

154,900,000

|

|

1,046,510,000

|

327,577,529

|

History of Qing-USA relations

Old China Trade

The result was the considerable exportation of specie, ginseng, and furs to China, and the much larger influx of tea, cotton, silk, lacquerware, porcelain, and furniture to the United States. The merchants, who served as middlemen between the Chinese and American consumers, became fabulously wealthy from this trade, eventually giving rise to America's first generation of millionaires. In addition, many Chinese artisans began to notice the American desire for exotic wares and adjusted their practices accordingly, manufacturing goods made specifically for export. These export wares often sported American or European motifs in order to fully capitalize on the consumer demographic.

Opium Wars

The end of the

First Opium War in 1842 led to the

Anglo-Chinese

Treaty of Nanking, which forced many Chinese ports open to foreign trade. Until then, American-Chinese relations had been conducted solely through trade, but this new pact between Britain and China severely threatened further American business in the region. The administration of President

John Tyler secured the 1844

Treaty of Wangxia, which not only put American trade on par with British trade, but also secured for Americans the right of

extraterritoriality. This treaty effectively ended the era of the Old China Trade, giving the United States as many trading privileges as other foreign powers.

After China's defeat in the Second Opium War, the Xianfeng emperor fled Beijing. His brother Yixin, the Prince Gong, ratified the Treaty of Tianjin in the Convention of Peking on October 18, 1860. This treaty stipulated, among other things, that along with Britain, France, and Russia, the United States would have the right to station legations in Beijing, a closed city at the time.

The Burlingame Treaty and the Chinese Exclusion Act

In 1868, the Qing government appointed

Anson Burlingame as their emissary to the United States. Burlingame toured the country to build support for equitable treatment for China and for Chinese emigrants. The 1868

Burlingame Treaty embodied these principles. In 1871, the

Chinese Educational Mission brought the first of two groups of 120 Chinese boys to study in the United States. They were led by

Yung Wing, the first Chinese man to graduate from an American university.

During the California Gold Rush and the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad, large numbers of Chinese emigrated to the US, spurring animosity from American citizens. After being forcibly driven from the mines, most Chinese settled in Chinatowns in cities such as San Francisco, taking up low-end wage labor, such as restaurant and laundry work. With the post-Civil War economy in decline by the 1870s, anti-Chinese animosity became politicized by labor leader Denis Kearney and his Workingman's Party, as well as by the California governor John Bigler. Both blamed Chinese coolies for depressed wage levels.

In the first significant restriction on free immigration in US history, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act on May 6, 1882, following revisions made in 1880 to the Burlingame Treaty. Those revisions allowed the United States to suspend immigration, and Congress acted quickly to implement the suspension of Chinese immigration and exclude Chinese "skilled and unskilled laborers and Chinese employed in mining" from entering the country for ten years, under penalty of imprisonment and deportation. The ban was renewed a number of times, lasting for over 60 years.

The Boxer Rebellion

In 1899, a movement of Chinese nationalists calling themselves the

Society of Right and Harmonious Fists started a violent revolt in China, referred to by Westerners as the

Boxer Rebellion, against foreign influence in trade, politics, religion, and technology. The

campaigns took place from November 1899 to September 7, 1901, during the final years of

Manchu rule in China under the

Qing Dynasty.

The uprising began as an anti-foreign, anti-imperialist, peasant-based movement in northern China. The insurgents attacked foreigners, who were building railroads and violating Feng shui, and Christians, who were held responsible for the foreign domination of China. In June 1900, the Boxers entered Peking, killing 230 foreign diplomats and foreigners as well as thousands of Chinese Christians, mostly in Shandong and Shanxi Provinces. On June 21, Empress Dowager Cixi declared war against all Western powers. Diplomats, foreign civilians, soldiers, and Chinese Christians were besieged during the Siege of Beijing Legation Quarter for 55 days. A coalition called the Eight-Nation Alliance comprising Austria-Hungary, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States rushed 20,000 troops to their rescue. The multinational forces were initially defeated by a Chinese Muslim army at the Battle of Langfang, but the second attempt was successful due to internal rivalries among the Chinese forces.

The Chinese government was forced to indemnify the victims and make many additional concessions. Subsequent reforms implemented after the rebellion contributed to the end of the Qing Dynasty and the establishment of the modern Chinese Republic. The United States played a secondary but significant role in suppressing the Boxer Rebellion, largely due to the presence of US ships and troops deployed in the Philippines since the American conquest of the Spanish–American and Philippine–American War. Within the United States Armed Forces, the suppression of the Boxer Rebellion was known as the China Relief Expedition.

Open Door Policy

In the late 19th century the major world powers (

France, the

United Kingdom,

Germany,

Italy,

Japan, and

Russia) began carving out spheres of influence for themselves in China, which was then under the

Qing Dynasty. The United States, not having such influence, wanted this practice to end. In 1899,

US Secretary of State John Hay sent diplomatic letters to these nations, asking them to guarantee the territorial and administrative integrity of China and to not interfere with the free use of

treaty ports within their respective spheres of influence. The major powers evaded commitment, saying they could not agree to anything until the other powers had consented first. Hay took this as acceptance of his proposal, which came to be known as the

Open Door Policy.

While generally respected internationally, the Open Door Policy did suffer serious setbacks. The first issue involved Russian encroachment in Manchuria in the late 1890s. The US protested Russia's actions, which led to a Russian war with Japan in 1904. Japan presented a further challenge to the Open Door Policy with its Twenty-One Demands in 1915 made on the then-Republic of China. Japan also made secret treaties with the Allies promising Japan the German territories in China. The biggest setback to the Open Door Policy came in 1931, when Japan invaded and occupied Manchuria, setting up the puppet state of Manchukuo. The United States, along with other countries, strongly condemned the action but did little at the time to stop it.

History of Republic of China and the USA relations

First few decades

After the

Xinhai Revolution in 1911, the

United States government recognized the

Republic of China (ROC) government as the sole and legitimate government of China despite

a number of governments ruling various parts of China. China was

reunified by a single government, ROC, led by the

Kuomintang (KMT) in 1928. The first winner of the

Nobel Prize in Literature for writing about China was an American, born in the United States but raised in China,

Pearl S. Buck, whose 1938 Nobel lecture was titled

The Chinese Novel.

World War II

The outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937 saw aid flow into the Republic of China, led by Chiang Kai-shek, from the United States, under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. A series of Neutrality Acts had been passed in the US with the support of isolationists who forbade American aid to countries at war. Because the Second Sino-Japanese War was undeclared, however, Roosevelt denied that a state of war existed in China and proceeded to send aid to Chiang.

American public sympathy for the Chinese was aroused by reports from missionaries, novelists such as Pearl Buck, and Time Magazine of Japanese brutality in China, including reports surrounding the notorious Nanking Massacre, also known as the 'Rape of Nanking'. Japanese-American relations were further soured by the USS Panay incident during the bombing of Nanking, in which a gunboat of the U.S. Navy was accidentally sunk by Japanese aircraft (whether or not it was in fact unintentional is disputed). Roosevelt demanded an apology and compensation from the Japanese, which was received, but relations between the two countries continued to deteriorate. Edgar Snow's 1937 book Red Star Over China reported that Mao Zedong's Chinese Communist Party was effective in carrying out reforms and guerrilla fighting the Japanese. When open war broke out in the summer of 1937, the United States offered moral support but took no effective action.

United States formally declared war on Japan in December 1941 following the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, which brought the Americans into World War II. The Roosevelt administration gave massive amounts of aid to Chiang's beleaguered government, now headquartered in Chungking. Madame Chiang Kai-shek, who had been educated in the United States, addressed the US Congress and toured the country to rally support for China. Congress amended the Chinese Exclusion Act and Roosevelt moved to end the unequal treaties. However, the perception that Chiang's government was unable to effectively resist the Japanese or that he preferred to focus more on defeating the Communists grew. China Hands such as Joseph "Vinegar Joe" Stilwell—who spoke fluent Mandarin Chinese—argued that it was in American interest to establish communication with the Communists to prepare for a land-based counteroffensive invasion of Japan. The Dixie Mission, which began in 1943, was the first official American contact with the Communists. Other Americans, such as Claire Chennault, argued for air power. In 1944, Generalissimo Chiang acceded to Roosevelt's request that an American general take charge of all forces in the area, but demanded that Stilwell be recalled. General Albert Wedemeyer replaced Stilwell, and Patrick Hurley became ambassador.

The American OSS (forerunner of the CIA) showed an interest in a plot to seize control of Chiang's regime. Chiang ordered the rebels involved executed. Chiang felt no friendliness towards the United States, and viewed it as pursuing imperialist motives in China. Chiang did not want to be subordinate to either the United States or the Soviet Union, but jockeyed for room between the two and wanted to get the most out of the Soviet Union and the Americans without taking sides. Abusive incidents had occurred with a drunk American General making comments about Chiang's regime, and the rape of two Chinese school girls by American marines.

Chiang did not like the Americans, and was suspicious of their motives. The American OSS, forerunner of the CIA, showed interest in a plot to seize control of Chiang's regime. Chiang ordered the plotters executed. Chiang felt no friendliness towards the United States, and saw the US as pursuing imperialist motives in China. Chiang did not want to be subordinate to either the United States or the Soviet Union, but jockeyed for position between the two to avoid taking sides and to get the most out of Soviet and American relationships. Chiang predicted that war would come between the Americans and Soviets and that they would both seek China's alliance, which he would use to China's advantage.

Chiang also differed from the Americans in ideology issues. He organized the Kuomintang as a Leninist-style party, oppressed dissent, and banned democracy, claiming it was impossible for China.

Chiang manipulated the Soviets and Americans during the war, at first telling the Americans that they would be welcome in talks between the Soviet Union and China, then secretly telling the Soviets that the Americans were unimportant and their opinions were to be left out. At the same time, Chiang positioned American support and military power in China against the Soviet Union as a factor in the talks, keeping the Soviets from taking advantage of China with the threat of American military action against the Soviets.

Chiang's right hand man, the secret police chief Dai Li, was both anti-American, and anti-Communist. Dai ordered Kuomintang agents to spy on American officers. Dai had previously been involved with the Blue Shirts Society, a Fascist-inspired paramilitary group in the Kuomintang that wanted to expel Western and Japanese imperialists, crush the Communists, and eliminate feudalism. Dai Li was assassinated in a plane crash orchestrated by the American OSS or the Communists.

Civil War in Mainland China

After World War II ended in 1945, the hostility between the Republic of China and the Communist Party of China exploded into open

civil war. The KMT lost effective control of

mainland China in the

Chinese Civil War in 1949. In the China White Paper (see

Dean Acheson#The White Paper Defense) in August 1949 drafted by the

State Department that the United States was announcing the hands-off policy to the ROC in Taiwan to the upcoming military attacks from the

People's Liberation Army. General

Douglas MacArthur directed the military forces under Chiang Kai-shek to go to the island of

Taiwan to accept the surrender of Japanese troops, thus beginning the military occupation of Taiwan. American general

George C. Marshall tried to broker a truce between the Republic of China and the Communist Party of China in 1946, but it quickly lost momentum. The

Nationalist cause declined until 1949, when the Communists emerged victorious and drove the Nationalists from the

Chinese mainland onto Taiwan and other islands.

Mao Zedong established the

People's Republic of China (PRC) in mainland China, while Taiwan and other islands are still retained under the Republic of China rule to this day.

Cold War relations

After

Korean War broke out, the

Truman Administration resumed economic and military aid to the ROC and neutralized

Taiwan Strait by

United States Seventh Fleet to stop a Communist invasion of Formosa. Until the US formally recognized the PRC in 1979, Washington provided ROC with financial grants based on the

Foreign Assistance Act,

Mutual Security Act and

Act for International Development enacted by the

US Congress. A separate

Sino-American Mutual Defense Treaty was signed between the two governments of US and ROC in 1954 and lasted until 1979.

The U.S. State Department's official position in 1959 was:

:That the provisional capital of the Republic of China has been at Taipei, Taiwan (Formosa) since December 1949; that the Government of the Republic of China exercises authority over the island; that the sovereignty of Formosa has not been transferred to China; and that Formosa is not a part of China as a country, at least not as yet, and not until and unless appropriate treaties are hereafter entered into. Formosa may be said to be a territory or an area occupied and administered by the Government of the Republic of China, but is not officially recognized as being a part of the Republic of China."

Termination of diplomatic relations between ROC and US

On January 1, 1979, the United States changed its diplomatic recognition of Chinese government from the ROC to the PRC. In the U.S.-PRC Joint Communiqué that announced the change, the United States recognized the Government of the PRC as the sole legal government of China and acknowledged the PRC position that there is but one China and Taiwan is part of China. The Joint Communiqué also stated that within this context the people of the United States will maintain cultural, commercial, and other unofficial relations with the people on Taiwan. Since then, the ROC has been referred by the United States government as 'Taiwan'.

Shortly before the termination of diplomatic relations, on December 28 and 29, 1978, shortly before Carter’s telegram message to China, a US representative was sent to the ROC for negotiations with ROC President Chiang Ching-Kuo. The content of these meetings mainly circled around the diplomatic state between the US and ROC after the American diplomatic reestablishment with the PRC. Upon arrival to Taipei, ROC’s capital, there was a great disturbance with the presence of the Americans. Understandably so, the Taiwanese people were angered by the “betrayal” of the US Government. There were several protests and the Americans, only with heavy security precautions, were able to navigate the city safely to and from meetings. The United States’ representative, following the President’s orders, attempted to negotiate four principal objectives that would, hopefully, provide a sort of compromise between the two nations. The first of these objectives was that “all treaties and agreements in force between [the two nations] will remain in effect after January 1, 1979, with each side retaining such rights or abrogation or termination as are provided in the treaties and agreements themselves or inherently in international law and practice.” The second objective of the negotiations was to continue operation of embassies and staff from January 1, 1979 until February 28, 1979. The third objective discussed was that the ROC and the US “will establish and put into operation … a new instrumentality … which would neither have the character of, nor be considered as, official governmental organizations.” The fourth and final objective was simply that the two nations would meet again to establish a more detailed plan regarding the future of the two nations.

History of People's Republic of China and the USA relations

Communist state in Mainland China

The United States did not formally recognize the People's Republic of China (PRC) for 30 years after its founding. Instead, the US maintained diplomatic relations with the Republic of China government on Taiwan, recognizing it as the sole legitimate government of

China.

However, the Taiwan-based Republic of China government did not trust the United States. An enemy of the Chiang family, Wu Kuo-chen, was removed from his position as governor of Taiwan by Chiang Ching-kuo and fled to America in 1953. Chiang Kai-shek, president of the Republic of China, suspected that the American CIA was engineering a coup with Sun Li-jen, an American-educated Chinese man who attended the Virginia Military Institute, with the goal of making Taiwan an independent state. Chiang placed Sun under house arrest in 1955.

Chiang Ching-kuo, educated in the Soviet Union, initiated Soviet-style military organization in the Republic of China military, reorganizing and Sovietizing the political officer corps and surveillance. Kuomintang party activities were propagated throughout the military. Sun Li-jen opposed this action.

As the People's Liberation Army moved south to complete the communist conquest of mainland China in 1949, the American embassy followed Chiang Kai-shek's Republic of China government to Taipei, while US consular officials remained in mainland China. However, the new PRC government was hostile to this official American presence, and all US personnel were withdrawn from mainland China in early 1950. In December 1950, the PRC seized all American assets and properties, totaling $196.8 million, after the US had frozen Chinese assets in America following China's entry into the Korean War in November.

Korean War

Any remaining hope of normalizing relations ended when US and PRC forces began fighting against each other in the

Korean War on November 1, 1950. In response to the Soviet-backed North Korean invasion of South Korea, the

United Nations Security Council was convened and passed

UNSC Resolution 82, condemning the North Korean aggression unanimously. The resolution was adopted mainly because the Soviet Union, a

veto-wielding power, had been boycotting UN proceedings since January, protesting that the

Republic of China and not the

People's Republic of China held a permanent seat on the council.

The American-led UN forces pushed the invading North Korean Army back into North Korea, past the North-South border at the 38th parallel and began to approach the Amnok river (Yalu river) on the China-North Korea border. As a result, the PRC undertook a massive intervention into the conflict on the side of the Communists. The Chinese struck in the west along the Chongchon River and completely overran several South Korean divisions, successfully landing a heavy blow to the flank of the remaining UN forces. The defeat of the US Eighth Army resulted in the longest retreat of any American military unit in history. Both sides sustained heavy casualties before the UN forces were able to push the PRC back, near the original division. In late March 1951, after the Chinese had moved large numbers of new forces near the Korean border, US bomb loading pits at Kadena Air Base in Okinawa were made operational. Bombs assembled there were "lacking only the essential nuclear cores." On April 5, the US Joint Chiefs of Staff released orders for immediate retaliatory attacks using atomic weapons against Manchurian bases to prevent new Chinese troops from entering the battles or bombing attacks originating from those bases. On the same day, Truman gave his approval for transfer of nine Mark IV nuclear capsules "to the Air Force's Ninth Bomb Group, the designated carrier of the weapons," signing an order to "use them against Chinese and Korean targets." Two years of continued fighting ended in a stalemate that lasted while negotiations dragged on, until the Korean Armistice Agreement was signed on July 27, 1953. Since then, the Division of Korea has had an important role in Sino-American relations. The entry of the Chinese in the Korean War caused a shift in US policy from marginal support of Chiang Kai-Shek's Nationalist government on Taiwan to full-blown defense of Taiwan from the PRC.

Vietnam War

The PRC's involvement in the Vietnam War began in 1949, when

mainland China was reunified under communist rule. The

Communist Party of China provided material and technical support to the Vietnamese communists. In the summer of 1962,

Mao Zedong agreed to supply Hanoi with 90,000 rifles and guns free of charge. After the launch of the American "Rolling Thunder" mission, China sent anti-aircraft units and engineering battalions to North Vietnam to repair the damage caused by American bombing, rebuild roads and railroads, and perform other engineering work, freeing North Vietnamese army units for combat in the South. Between 1965 and 1970, over 320,000 Chinese soldiers fought the Americans alongside the

North Vietnamese Army, reaching a peak in 1967, when 170,000 troops served in combat. China lost 1,446 troops in the Vietnam War. The US lost 58,159 in combat against the NVA, Vietcong, and their allied forces, including the Chinese.

Relations frozen

The United States continued to work to prevent the PRC from taking China's seat in the

United Nations and encouraged its allies not to deal with the PRC. The United States placed an embargo on trading with the PRC, and encouraged allies to follow it. The

PRC developed nuclear weapons in 1964 and, as later declassified documents revealed, President Johnson considered preemptive attacks to halt its nuclear program. He ultimately decided the measure carried too much risk and it was abandoned.

Despite this official non-recognition, the United States and the People's Republic of China held 136 meetings at the ambassadorial level beginning in 1954 and continuing until 1970, first in Geneva and later in Warsaw.

Beginning in 1967, the Foreign Claims Settlement Commission established the China Claims Program, in which American citizens could denominate the sum total of their lost assets and property following the Communist seizure of foreign property in 1950. In the program's scope were “(1) losses resulting from the nationalization, expropriation, intervention, or other taking of, or special measures directed against, property or nationals of the United States; and (2) disability or death, resulting from actions taken by or under the authority of the Chinese Communist regime.” Any American citizen who had lost property in China following the declaration of the People's Republic of China on October 1, 1949, was entitled to file a claim with the Commission. Claimants included the Chinese Medical Board of New York, which operated the Peking Union Medical College, Esso Standard (the predecessor of Exxon Mobil), which owned the Shanghai Power Company, and American Express, which fled China in September 1949 amid Civil War and hyperinflation. In retaliation for unsettled accounts with Chinese citizens, the PRC refused to grant an exit visa to an American Express employee, who remained in China for five years. Because of the expropriation of assets, American companies would remain hesitant to reinvest in China despite (future Chairman) Deng Xiaoping's reassurances of a stable business environment.

Rapprochement

:

The end of 60s brought a period of transformation. For China, when American president Johnson decided to wind down the Vietnam war in 1968, it gave China an impression that the US had no interest of expanding in Asia anymore while the USSR became a more serious threat as it intervened in Czechoslovakia to displace a communist government and might well interfere in China.

.

This became an especially important concern for the People's Republic of China after the Sino-Soviet border clashes of 1969. The PRC was diplomatically isolated and the leadership came to believe that improved relations with the United States would be a useful counterbalance to the Soviet threat. Zhou Enlai, the PRC premier foreign minister, was at the forefront of this effort with the committed backing of Mao Zedong.

In the United States, academics such as John K. Fairbank and A. Doak Barnett pointed to the need to deal realistically with the Beijing government, while organizations such as the National Committee on United States-China Relations sponsored debates to promote public awareness. Many saw the specter of Communist China behind Communist movements in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos, but a growing number concluded that if the PRC would align with the US it would mean a major redistribution of global power against the Soviets. Mainland China's market of nearly one billion consumers appealed to American business. Senator William Fulbright, Chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, held a series of hearings on the matter.

Mike Mansfield, the Democratic Senate Majority Leader was indirectly approached by the PRC and passed a note on to the State Department and President Richard Nixon.

As president Richard. M. Nixon mentioned in his inaugural address, they were entering an era of negotiation after an era of confrontation. Nixon was a person who worked since in 1947 to 1952 in Congress and as a Vice President from 1953 to 1961 in making confrontational American policies against the Soviet and Communism. However after Nixon became president, with his National Security Advisor, Henry Kissinger admitted that the world had changed to the growth of multipolarity

Nixon believed it necessary to forge a relationship with China, even though there were enormous differences between the two countries. He was assisted in this by his National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger. Domestic political concerns also entered into Nixon's thinking, as the boost from a successful courting of the PRC could help him greatly in the 1972 American presidential election. He also worried immensely that one of the Democrats would preempt him and go to the PRC before he had the opportunity.

Communication between Chinese and American leaders was conducted with Pakistan and Poland as intermediaries.

In 1969, the United States initiated measures to relax trade restrictions and other impediments to bilateral contact, to which China responded. However, this rapprochement process was stalled by US actions in Indochina.

On April 6, 1971, the young American ping pong player Glenn Cowan missed his US team bus and was waved by a Chinese table tennis player onto the bus of the Chinese team at the 31st World Table Tennis Championships in Nagoya, Japan. Cowan spoke with the Chinese players in a friendly fashion, and the Chinese player, Zhuang Zedong, a three-time World Men's Singles Champion, presented him with a silk-screen portrait of the famous Huangshan Mountains. While this had been a purely spontaneous gesture of friendship between two athletes, the PRC chose to treat it as an officially sanctioned outreach. Henry Kissinger also believed that it was planned. Zhuang Zedong spoke about the incident in a 2007 talk at the USC US-China Institute. According to sources from the PRC, the friendly contact between Zhuang Zedong and Glenn Cowan, as well as the photograph of the two players in Dacankao, had an impact on Mao's decision making. He had earlier decided not to invite the US team to tour mainland China along with teams of other western countries, but in a move later known as Ping Pong Diplomacy, Mao and the PRC invited the American ping pong team to tour after all. The Americans agreed and on April 10, 1971 the athletes became the first Americans to officially visit China since the communist revolution in 1949.

In July 1971, Henry Kissinger feigned illness while on a trip to Pakistan and did not appear in public for a day. He was actually on a top-secret mission to Beijing to open relations with the government of the PRC. On July 15, 1971, President Richard Nixon revealed the mission to the world and that he had accepted an invitation to visit the PRC.

This announcement caused immediate shock around the world. In the United States, some of the most hardline anti-communists spoke against the decision, but public opinion supported the move and Nixon saw the jump in the polls he had been hoping for. Since Nixon had sterling anti-communist credentials he was all but immune to being called "soft on communism." Nixon and his aides wanted to ensure that coverage of the trip emphasized the bold initiative and offered dramatic imagery. See "Getting to know you: The US and China shake the world" and "The Week that Changed the World" for recordings, documents, and interviews. Nixon was particularly eager for strong news coverage.

Within the PRC there was also opposition from left-wing elements. This effort was allegedly led by Lin Biao, head of the military, who died in a mysterious plane crash over Mongolia while trying to defect to the Soviet Union. His death silenced most internal dissent over the visit.

Internationally, reactions varied. The Soviets were very concerned that two major enemies seemed to have resolved their differences, and the new world alignment contributed significantly to the policy of détente.

America's European allies and Canada were pleased by the initiative, especially since many of them had already recognized the PRC. In Asia, the reaction was far more mixed. Japan was annoyed that it had not been told of the announcement until fifteen minutes before it had been made, and feared that the Americans were abandoning them in favor of the PRC. A short time later, Japan also recognized the PRC and committed to substantial trade with the continental power. South Korea and South Vietnam were both concerned that peace between the United States and the PRC could mean an end to American support for them against their Communist enemies. Throughout the period of rapprochement, both countries had to be regularly assured that they would not be abandoned.

From February 21 to February 28, 1972, President Nixon traveled to Beijing, Hangzhou, and Shanghai. At the conclusion of his trip, the US and the PRC issued the Shanghai Communiqué, a statement of their respective foreign policy views. In the Communiqué, both nations pledged to work toward the full normalization of diplomatic relations. This did not lead to immediate recognition of the People's Republic of China but 'liaison offices' were established in Beijing and Washington. The US acknowledged the PRC position that all Chinese on both sides of the Taiwan Strait maintain that there is only one China and that Taiwan is part of China. The statement enabled the US and PRC to temporarily set aside the issue of Taiwan and open trade and communication. Also, the USA and China both agreed to take action against 'any country' that is to establish 'hegemony' in the Asia-Pacific.

The rapprochement with the United States benefited the PRC immensely and greatly increased its security for the rest of the Cold War. It has been argued that the United States, on the other hand, saw fewer benefits than it had hoped for. The PRC continued to heavily support North Vietnam in the Vietnam War and also backed the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia. Eventually, however, the PRC's suspicion of Vietnam's motives led to a break in Sino-Vietnamese cooperation and, upon the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia in 1979, the Sino-Vietnamese War. Both China and the United States backed combatants in Africa against Soviet and Cuban-supported movements. The economic benefits of normalization were slow as it would take decades for American products to penetrate the vast Chinese market. While Nixon's China policy is regarded by many as the highlight of his presidency, others such as William Bundy have argued that it provided very little benefit to the United States.

Liaison Office, 1973–1978

In May 1973, in an effort to build toward formal diplomatic relations, the US and the PRC established the United States Liaison Office (USLO) in Beijing and a counterpart PRC office in Washington, DC. In the years between 1973 and 1978, such distinguished Americans as David K. E. Bruce, George H. W. Bush, Thomas S. Gates, and Leonard Woodcock served as chiefs of the USLO with the personal rank of Ambassador.

President Gerald Ford visited the PRC in 1975 and reaffirmed American interest in normalizing relations with Beijing. Shortly after taking office in 1977, President Jimmy Carter again reaffirmed the goals of the Shanghai Communiqué. Carter's National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski and senior staff member of the National Security Council Michel Oksenberg encouraged Carter to seek full diplomatic and trade relations with China. Brzezinski and Oksenberg traveled to Beijing in early 1978 to work with Leonard Woodcock, then head of the liaison office, to lay the groundwork to do so. The United States and the People's Republic of China announced on December 15, 1978 that the two governments would establish diplomatic relations on January 1, 1979.

Normalization to Beijing

After the announcement of the establishment of diplomatic relations with the PRC on 15 December 1978, the President of the Republic of China, Chiang Ching-Kuo immediately condemned the USA for its actions. This was followed by rampant protests in both the ROC and the US; despite this, Carter proceeded to forge relations with the PRC.

In the Joint Communiqué on the Establishment of Diplomatic Relations, dated January 1, 1979, the United States transferred diplomatic recognition from Taipei to Beijing. The US reiterated the Shanghai Communiqué's acknowledgment of the Chinese position that there is only one China and that Taiwan is a part of China; Beijing acknowledged that the American people would continue to carry on commercial, cultural, and other unofficial contacts with the people of Taiwan. The Taiwan Relations Act (text) made the necessary changes in US domestic law to permit such unofficial relations with Taiwan to flourish.

Vice Premier Deng Xiaoping's January 1979 visit to Washington, DC initiated a series of important, high-level exchanges which continued until the spring of 1989. This resulted in many bilateral agreements, especially in the fields of scientific, technological, and cultural interchange, as well as trade relations. Since early 1979, the United States and the PRC have initiated hundreds of joint research projects and cooperative programs under the Agreement on Cooperation in Science and Technology, the largest bilateral program.

On March 1, 1979, the United States and the People's Republic of China formally established embassies in Beijing and Washington, DC. In 1979, outstanding private claims were resolved and a bilateral trade agreement was completed. Vice President Walter Mondale reciprocated Vice Premier Deng's visit with an August 1979 trip to China. This visit led to agreements in September 1980 on maritime affairs, civil aviation links, and textile matters, as well as a bilateral consular convention.

As a consequence of high-level and working-level contacts initiated in 1980, New York City and Beijing become sister cities, US dialogue with the PRC broadened to cover a wide range of issues, including global and regional strategic problems, political-military questions, including arms control, UN, and other multilateral organization affairs, and international narcotics matters.

The expanding relationship that followed normalization was threatened in 1981 by PRC objections to the level of US arms sales to the Republic of China on Taiwan. Secretary of State Alexander Haig visited China in June 1981 in an effort to resolve Chinese concerns about America's unofficial relations with Taiwan. Vice President Bush visited the PRC in May 1982. Eight months of negotiations produced the US-PRC Joint Communiqué of August 17, 1982. In this third communiqué, the US stated its intention to gradually reduce the level of arms sales to the Republic of China, and the PRC described as a fundamental policy their effort to strive for a peaceful resolution to the Taiwan question.

High-level exchanges continued to be a significant means for developing US-PRC relations in the 1980s. President Ronald Reagan and Premier Zhao Ziyang made reciprocal visits in 1984. In July 1985, President Li Xiannian traveled to the United States, the first such visit by a PRC head of state. Vice President Bush visited the PRC in October 1985 and opened the US Consulate General in Chengdu, the US's fourth consular post in the PRC. Further exchanges of cabinet-level officials occurred between 1985 and 1989, capped by President Bush's visit to Beijing in February 1989.

In the period before the June 3–4, 1989 crackdown, a growing number of cultural exchange activities gave the American and Chinese peoples broad exposure to each other's cultural, artistic, and educational achievements. Numerous mainland Chinese professional and official delegations visited the United States each month. Many of these exchanges continued after the suppression of the Tiananmen protests.

Tian'anmen to September 11th, 2001

Following the PRC's violent suppression of demonstrators in June 1989, the US and other governments enacted a number of measures to express their condemnation of the PRC's violation of

human rights. The US suspended high-level official exchanges with the PRC and weapons exports from the US to the PRC. The US also imposed a number of

economic sanctions. In the summer of 1990, at the

G7 Houston summit, Western nations called for renewed political and economic reforms in mainland China, particularly in the field of human rights.

Tian'anmen disrupted the US-PRC trade relationship, and US investors' interest in mainland China dropped dramatically. The US government responded to the political repression by suspending certain trade and investment programs on June 5 and 20, 1989. Some sanctions were legislated while others were executive actions. Examples include:

The US Trade and Development Agency (TDA): new activities in mainland China were suspended from June 1989 until January 2001, when President Bill Clinton lifted this suspension.

Overseas Private Insurance Corporation (OPIC): new activities have been suspended since June 1989.

Development Bank Lending/International Monetary Fund (IMF) Credits: the United States does not support development bank lending and will not support IMF credits to the PRC except for projects that address basic human needs.

Munitions List Exports: subject to certain exceptions, no licenses may be issued for the export of any defense article on the US Munitions List. This restriction may be waived upon a presidential national interest determination.

Arms Imports - import of defense articles from the PRC was banned after the imposition of the ban on arms exports to the PRC. The import ban was subsequently waived by the Administration and reimposed on May 26, 1994. It covers all items on the

Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms'

Munitions Import List. During this critical period, J. Stapleton Roy, a career US Foreign Service Officer, served as ambassador to Beijing.

In 1996, the PRC conducted military exercises in the Taiwan Strait in an apparent effort to intimidate the Republic of China electorate before the pending presidential elections, triggering the Third Taiwan Straits Crisis. The United States dispatched two aircraft carrier battle groups to the region. Subsequently, tensions in the Taiwan Strait diminished and relations between the US and the PRC improved, with increased high-level exchanges and progress on numerous bilateral issues, including human rights, nonproliferation, and trade. President Jiang Zemin visited the United States in the fall of 1997, the first state visit to the US by a PRC president since 1985. In connection with that visit, the two sides came to a consensus on implementation of their 1985 agreement on Peaceful Nuclear Cooperation, as well as a number of other issues. President Clinton visited the PRC in June 1998. He traveled extensively in mainland China, and had direct interaction with the Chinese people, including live speeches and a radio show which allowed the President to convey a sense of American ideals and values. President Clinton was criticized by some, however, for failing to pay adequate attention to human rights abuses in mainland China.

Relations between the US and the PRC were severely strained for a time by the NATO Bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade in May 1999, which was blamed on an intelligence error but which some Chinese believed to be deliberate. By the end of 1999, relations began to gradually improve. In October 1999, the two sides reached an agreement on humanitarian payments for families of those who were injured or killed, as well as payments for damages to respective diplomatic properties in Belgrade and China.

In April 2001, a PRC J-8 fighter jet collided with a US EP-3 reconnaissance aircraft flying south of the PRC in what became known as the Hainan Island incident. The EP-3 was able to make an emergency landing on PRC's Hainan Island despite extensive damage; the PRC aircraft crashed with the loss of its pilot, Wang Wei. It was widely believed that the EP-3 recon aircraft was conducting a spying mission on the Chinese Armed Forces before the collision. Following extensive negotiations resulting in the "letter of the two sorries," the crew of the EP-3 was released from imprisonment and allowed to leave the PRC 11 days later. The US aircraft was not permitted to depart Chinese soil for another three months, after which the relationship between the US and the PRC gradually improved once more.

Bush administration

Sino-American relations changed radically following the September 11, 2001 attacks. Two PRC citizens died in the September 11, 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center, and mainland Chinese companies and individuals sent expressions of condolences to their US counterparts. The PRC offered strong public support for the war on terrorism. The PRC voted in favor of UNSCR 1373, publicly supported the coalition campaign in Afghanistan, and contributed $150 million of bilateral assistance to Afghan reconstruction following the defeat of the Taliban. Shortly after 9/11, the US and PRC also commenced a counterterrorism dialogue. The third round of that dialogue was held in Beijing in February 2003.

In the United States, the terrorist attacks greatly changed the nature of discourse. It was no longer plausible to argue, as the Blue Team had earlier asserted, that the PRC was the primary security threat to the United States, and the need to focus on the Middle East and the War on Terror made the avoidance of potential distractions in East Asia a priority for the United States.

There were initial fears among the PRC leadership that the war on terrorism would lead to an anti-PRC effort by the US, especially as the US began establishing bases in Central Asian countries like Uzbekistan and Tajikistan and renewed efforts against Iraq. Because of setbacks in America's Iraq campaign, these fears have largely subsided. The application of American power in Iraq and continuing efforts by the United States to cooperate with the PRC has significantly reduced the popular anti-Americanism that had developed in the mid-1990s.

The PRC and the US have also worked closely on regional issues, including those pertaining to North Korea and its nuclear weapons program. The People's Republic of China has stressed its opposition to North Korea's decision to withdraw from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, its concerns over North Korea's nuclear capabilities, and its desire for a non-nuclear Korean peninsula. It also voted to refer North Korea's noncompliance with its International Atomic Energy Agency obligations to the UN Security Council.

Taiwan remains a volatile issue, but one that remains under control. The United States policy toward Taiwan has involved emphasizing the Four Noes and One Without. On occasion the United States has rebuked Republic of China President Chen Shui-bian for provocative pro-independence rhetoric. However, in 2005, the PRC passed an anti-secession law which stated that the PRC would be prepared to resort to "non-peaceful means" if Taiwan declared formal independence. Many critics of the PRC, such as the Blue Team, argue that the PRC was trying to take advantage of the US war in Iraq to assert its claims on Republic of China's territory. In 2008, Taiwan voters elected Ma Ying-jeou. Ma, representing the Kuomintang, campaigned on a platform that included rapprochement with mainland China. His election has significant implications for the future of cross-strait relations.

China's president Hu Jintao visited the United States in April 2006.

Clark Randt, U.S. Ambassador to China from 2001 to 2008 examined "The State of U.S.-China Relations in a 2008 lecture at the USC U.S.-China Institute.

Obama administration

The 2008 US presidential election centered on issues of war and economic recession, but candidates

Barack Obama and

John McCain also spoke extensively regarding US policy toward China. Both favored cooperation with China on major issues, but they differed with regard to trade policy. Obama expressed concern that the value of China's currency was being deliberately set low to benefit China's exporters. McCain argued that free trade was crucial and was having a transformative effect in China. Still, McCain noted that while China might have shared interests with the US, it did not share American values.

Barack Obama's presidency has fostered hopes for increased co-operation and heightened levels of friendship between the two nations. On November 8, 2008, Hu Jintao and Barack Obama shared a phone conversation in which the Chinese President congratulated Obama on his election victory. During the conversation both parties agreed that the development of US-China relations is not only in the interest of both nations, but also in the interests of the world.

Other organizations within China also held positive reactions to the election of Barack Obama, particularly with his commitment to revising American climate change policy. Greenpeace published an article detailing how Obama's victory would spell positive change for investment in the green jobs sector as part of a response to the financial crisis gripping the world at the time of Obama's inauguration. A number of organizations, including the US Departments of Energy and Commerce, NGOs such as the Council on Foreign Relations and the Brookings Institution, and universities, have been working with Chinese counterparts to discuss ways to address climate change. Both US and Chinese governments have addressed the economic downturn with massive stimulus initiatives. The Chinese have expressed concern that "Buy American" components of the US plan discriminate against foreign producers, including those in China.

As the two most influential and powerful countries in the world, there have been increasingly strong suggestions within American political circles of creating a G-2 (Chimerica) relationship for the United States and China to work out solutions to global problems together.

The Strategic Economic Dialogue initiated by then-US President Bush and Chinese President Hu and led by US Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson and Chinese Vice Premier Wu Yi in 2006 has been broadened by the Obama administration. Now called the US-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue it is led by US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and US Secretary of the Treasury Timothy Geithner for the United States and Vice Premier Wang Qishan and Chinese State Councilor Dai Bingguo for China. The focus of the first set of meetings in July 2009 was in response to the economic crisis, finding ways to cooperate to stem global warming and addressing issues such as the proliferation of nuclear weapons and humanitarian crises.

US President Barack Obama visited China on November 15–18, 2009 to discuss economic worries, concerns over nuclear weapon proliferation, and the need for action against climate change. The USC US-China Institute produced a digest of press comments on this visit and on earlier presidential trips.

In January 2010, the US proposed a $6.4 billion arms sale to the Republic of China. In response, the PRC threatened to impose sanctions on US companies supplying arms to Taiwan and suspend cooperation on certain regional and international issues.

On February 19, 2010, President Obama met with the Dalai Lama, accused by China of "fomenting unrest in Tibet." After the meeting, China summoned the US ambassador to China, Jon Huntsman, but Time has described the Chinese reaction as "muted," speculating that it could be because "the meeting came during the Chinese New Year... when most officials are on leave." Some activists criticized Obama for the relatively low profile of the visit.

In 2012, the PRC criticized Obama's new defense strategy, which was widely viewed as aiming to isolate China in the East Asian region, for assuming a provocative and threatening posture in the Pacific and escalating America's containment strategy. Obama is looking to increase US military influence in the area with a rotating presence of forces in friendly countries.

In March 2012 China suddenly began cutting back its purchases of oil from Iran, along with some signs on sensitive security issues like Syria and North Korea, showed some coordination with the Obama administration.

A PLA-affiliated hacking group based outside Shanghai has been responsible for more than 100 attacks on United States government departments, American companies, and journalist website, according to an American computer security firm, Mandiant. A national intelligence estimate by multiple American intelligence agencies concur with the report. A White House official said that the United States will be "more-aggressive" in responding to cyberwarfare amd cyberespionage conducted by the Chinese government. Cyberespionage originating from China has also been reported by companies in France and Germany. China responded by saying that the accusations of hacking are flawed and unreliable, and accused the United States of being the origin of attacks against Chinese military websites.

In March 2013, the US and China agreed to impose stricter sanctions on North Korea for conducting nuclear tests, which sets the stage for UN Security Council vote. Such accord might signal a new level of cooperation between the US and China.

In an effort to build a “new model” of relations, President Obama met President Xi Jinping for two days of meetings, between 6 June and 8 June 2013, at the Sunnylands estate in Rancho Mirage, California. The summit was considered “the most important meeting between an American president and a Chinese leader in 40 years, since Nixon and Mao,” according to Joseph Nye, a political scientist at Harvard University. The leaders concretely agreed to combat climate change and also found strong mutual interest in curtailing North Korea’s nuclear program. However, the leaders remained sharply divided over cyber espionage and U.S. arms sales to Taiwan. Xi was dismissive of American complaints about cyber security. Tom Donilan, the outgoing U.S. National Security Adviser, stated that cyber security "is now at the center of the relationship,” adding that if China’s leaders were unaware of this fact, they know now.

Relations between the military leadership of the two nations improved in 2013. General Qi said that over the long term the shared interests of the two would outweigh their differences. Meanwhile he called for vigilance against "infiltration and subversion" by the West, and "interference by outside powers" in the South China Sea."

Important issues

Theoretical Economic Forecasts

The

World Bank's chief economist Justin Lin in 2011 stated that China, which became the world's second largest economy in 2010, may become the world's largest economy in 2030, overtaking the United States, if current trends continue. Challenges include income inequality and pollution. The

Standard Chartered Bank in a 2011 report suggested that China may become the world's largest economy in 2020. A 2007 OECD rapport by Angus Maddison estimated that if using

purchasing power parity conversions, then China will overtake the United States in 2015. James Wolfensohn, former World Bank president, estimated in 2010 that by 2030 two-thirds of the world's

middle class will live in China.

Official PRC Perspective on US Economy

China is a major creditor nation and the largest foreign holder of U.S. public debt and has been a vocal critic of U.S. deficits and fiscal policy. China has repeatedly appealed for the safeguarding of Chinese investments in U.S. treasuries and called for policies that maintain the purchasing value of the Dollar. Responding to S&P;'s downgrade of U.S. credit rating, China was scathing in its criticism of U.S. fiscal policy. It advised that U.S. must stop its "addiction to debt", urged the U.S. to use "common sense" in pursuing fiscal balance and "learn to live within its means", and warned that "the US government has to come to terms with the painful fact that the good old days when it could just borrow its way out of messes of its own making are finally gone".

In August 2011, when Standard & Poor's downgraded the U.S. government's credit rating, the New China News Agency, which served most of the media in China, editorialized: "China, the largest creditor of the world's sole superpower, has every right now to demand the United States address its structural debt problems and ensure the safety of China's dollar assets."

US-China economic relations

The PRC and the US resumed trade relations in 1972 and 1973. Direct investment by the US in mainland China covers a wide range of manufacturing sectors, several large hotel projects, restaurant chains, and

petrochemicals. US companies have entered agreements establishing more than 20,000 equity

joint ventures, contractual joint ventures, and wholly foreign-owned enterprises in mainland China. More than 100 US-based multinationals have projects in mainland China, some with multiple investments. Cumulative US investment in mainland China is valued at $48 billion. The US trade deficit with mainland China exceeded $350 billion in 2006 and was the United States' largest bilateral trade deficit. Some of the factors that influence the U.S. trade deficit with mainland China include:

US Import Valuation Overcounts China: there has been a shift of low-end assembly industries to mainland China from newly industrialized countries in Asia. Mainland China has increasingly become the last link in a long chain of value-added production. Because US trade data attributes the full value of a product to the final assembler, mainland Chinese value added is overcounted.

US demand for labor-intensive goods exceeds domestic output: the PRC has restrictive trade practices in mainland China, which include a wide array of barriers to foreign goods and services, often aimed at protecting state-owned enterprises. These practices include high tariffs, lack of transparency, requiring firms to obtain special permission to import goods, inconsistent application of laws and regulations, and leveraging technology from foreign firms in return for market access. Mainland China's accession to the World Trade Organization is meant to help address these barriers.

The undervaluation of the

Renminbi relative to the

US dollar.

Beginning in 2009, the US and China agreed to hold regular high-level talks about economic issues and other mutual concerns by establishing the China-US strategic economic dialogue, which meets biannually. Five meetings have been held, the most recent in December 2008. Economic nationalism seems to be rising in both countries, a point the leaders of the two delegations noted in their opening presentations. The United States and China have also established the high-level US-China Senior Dialogue to discuss international political issues and work out resolutions.

In September 2009 a trade dispute emerged between China and the United States, which came after the US imposed tariffs of 35 percent on Chinese tire imports. The Chinese commerce minister accused the United States of a "grave act of trade protectionism," while a USTR spokesperson said the tariff "was taken precisely in accordance with the law and our international trade agreements." Additional issues were raised by both sides in subsequent months.

Pascal Lamy cautioned: "The statistical bias created by attributing commercial value to the last country of origin perverts the true economic dimension of the bilateral trade imbalances. This affects the political debate, and leads to misguided perceptions. Take the bilateral deficit between China and the US. A series of estimates based on true domestic content can cut the overall deficit – which was $252bn in November 2010 – by half, if not more."

Currency dispute

Monetary policy has been one of the biggest issues surrounding relations between the United States and China within the past decade. At the heart of the issue is the question of whether or not each country’s currency is at the proper value. Each country has placed the blame with the other. Most monetary and trade experts agree that China’s currency has been and is still undervalued, but an article by

Business Insider argues that China raising the value of their currency would have a large effect on the trade balance between the two countries.

Domestic leaders within the United States have pressured the Obama Administration to take a hard line against China and compel them to raise the value of their currency. The United States Congress currently has before it a bill which would call on the President to impose tariffs on Chinese imports until China properly values its currency. Many Congressional members from states with large manufacturing sectors are leading the push to retaliate against China. The Chinese state newspaper has criticized the United States for unfair monetary policies as well. Both countries have sought out other international partners to side with them.

Military spending and planning

The PRC's

military budget is often mentioned as a threat by many, including the

Blue Team in the

United States. The PRC's investment in its military is growing rapidly. The United States, along with independent analysts, remains convinced that the PRC conceals the real extent of its military spending. According to the PRC government, China spent $45 billion on defense in 2007. In contrast, the United States had a $623-billion budget for the military in 2008, $123 billion more than the combined military budgets of all other countries in the world. Some very broad US estimates maintain that the PRC military spends between $85 billion and $125 billion. According to official figures, the PRC spent $123 million on defense per day in 2007. In comparison, the US spent $1.7 billion ($1,660 million) per day that year.

The concerns over the Chinese military budget may come from US worries that the PRC is attempting to threaten its neighbors or challenge the United States. Concerns have been raised that China is developing a large naval base near the South China Sea and has diverted resources from the People's Liberation Army Ground Force to the Peoples Liberation Army Navy and to air force and missile development. Even still, China's military spending is only a fourth of US spending.

Andrew Scobell wrote that under President Hu, objective civilian control and oversight of the PLA appears to be weakly applied.

On October 27, 2009, American Defense Secretary Robert Gates praised the steps China has taken to increase transparency of defense spending. In June 2010, however, he said that the Chinese military was resisting efforts to improve military-to-military relations with the United States. Gates has also said that the United States will "assert freedom of navigation" in response to Chinese complaints about United States Navy deployments in international waters near China. Admiral Mike Mullen has said that the United States seeks closer military ties to China, but will continue to operate in the western Pacific.

A recent report stated that five of six US Air Force bases in the area are potentially vulnerable to Chinese missiles and called for increased defenses.

Meanwhile, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists wrote in a 2010 report that the Chinese continue to invest in modernization of their nuclear forces because they perceive that their deterrent force is vulnerable to American capabilities and that further improvement in American missile defenses will drive further Chinese spending in this area.

Chinese defense minister Liang Guanglie has said that China is 20 years behind the United States in military technology.

Vladimir Dvorkin of the Russian Academy of Sciences has said that the USA's missile defense systems pose a real threat to China's nuclear deterrence.

The International Institute for Strategic Studies in a 2011 report argued that if spending trends continue China will achieve military equality with the United States in 15–20 years.

China and the United States have been described as engaging in a military and technological race. Expansion and development of new weapons by China has been seen as so threatening as to cause planning for withdrawal of US forces from close proximity to China, dispersal of US bases in the region, and development of various new weapon systems. China is also developing capacity for attacking satellites and for cyberwarfare.

In order to facilitate China's "growing global role", the United States has invited a team of senior Chinese logisticians to discuss a logistics cooperation agreement.

Professor James R. Holmes, Chinese specialist at the U.S. Naval War College, has said that China's investments towards a potential future conflict are closer to those of the United States than may first appear, because the Chinese understate their spending, the internal price structures of the two countries are different, and the Chinese only need to concentrate on projecting military force a short distance from their own shores. The balance may shift to the advantage of the Chinese very quickly if they continue double digit yearly growth while the Americans and their allies cut back.

In line with power transition theory, the idea that "wars tend to break out...when the upward trajectory of a rising power comes close to intersecting the downward trajectory of a declining power," some have argued that conflict between China, an emerging power, and the United States, the reigning superpower, is all but inevitable. However, the current leadership in China shows no sign of holding an expansionist ideology and Chinese leaders use the phrase "China's peaceful rise" to describe the country's trajectory. Furthermore, a number of domestic challenges in China, including environmental degradation, political corruption, and the increasing quality of life demands of the emerging middle class, may prevent China from pursuing an aggressive foreign policy or taking on the global hegemony of the United States anytime soon. If that is the case, a policy of accommodation, as opposed to containment, on the part of the U.S. may decrease the likelihood of conflict between the two countries.

Space

The

Chinese space program is expanding at a time when the

United States space program has been seen as in retreat. China in a 2007 test shot down a satellite which was quickly followed by the United States in 2008 also using a missile to shoot down a satellite.

Republic of China (Taiwan)

The

Republic of China remains a source of tension in relations between the United States and the

People's Republic of China. Although the PRC has never governed Taiwan, the PRC claims Taiwan as a 23rd province and has repeatedly threatened to take it by force. The United States exports large amounts of weaponry to the Republic of China and there is a great deal of sympathy for Taiwan partly because it, unlike the PRC, has transformed into a

pluralistic,

liberal democracy and because of residual sympathy over the Republic of China's anti-communism during the Cold War. Any accession to the PRC may also change the balance of power in that region in both political and military terms. This potentiality has been of increasing concern to Japan, a traditional ally of Taiwan and an ally of the Republic of China since its relocation to Taipei.

Officially, US policy is governed by the Taiwan Relations Act (text), the Six Assurances, and the Three Communiques. It has stated a commitment to a One China Policy in which it acknowledges the PRC's position that Taiwan is part of China, but does not indicate whether it agrees with that position. The strength of that commitment and the relationship between these policies, which may seem contradictory, changes from administration to administration.

In Taiwan, there is a general public consensus in favor of the status quo. However, some supporters of Taiwan independence, such as Lee Teng-hui, have expressed the idea that Taiwan must act quickly to formally declare independence because the long-term trends favor increased Chinese economic and military power. Given the PRC's threats to invade if Taiwan formally declares independence, and the United States' commitments to Taiwan in the Taiwan Relations Act, such a declaration would put the US in a difficult position. In several cases in which the administration of Chen Shui-bian appeared to be moving away from the status-quo and toward de jure independence, the United States asked for and received assurances that the Republic of China remains committed to the "Four Noes and One Without" policy.

In the last months of the Bush administration, Taipei reversed the secular trend of declining defense spending at a time when most Asian countries continued to reduce their military expenditures. It also decided to modernize both defensive and offensive capabilities. Taipei still keeps a large military apparatus relative to the island’s population: defense expenditures for 2008 were NTD 334 billion (approximately US $10.5 billion), which accounted for 2.94% of the GDP.

On January 30, 2010, the Obama administration announced it intended to sell $6.4 billion worth of antimissile systems, helicopters, and other military hardware to Taiwan. This move, expected under the American Taiwan Relations Act, drew a forceful reaction from Beijing. In retaliation, China warned the United States that their cooperation on international and regional issues could suffer over the administration's decision to sell arms to Taiwan. China further announced that it might penalize some of the companies involved in building the hardware for Taiwan, including Boeing, Lockheed Martin, and Raytheon.

A 2008 report by the RAND Corporation analyzing a theoretical 2020 attack by mainland China on Taiwan suggested that the US would likely not be able to defend Taiwan.

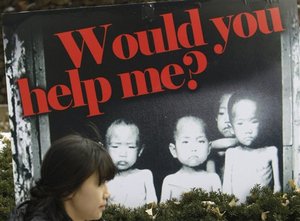

Human rights

In 2003 the United States declared that despite some positive momentum that year and greater signs that the People's Republic of China was willing to engage with the US and others on

human rights, there was still serious backsliding. The PRC government has acknowledged in principle the importance of protection of human rights in mainland China and has claimed to have taken steps to bring its human rights practices into conformity with international norms. Among these steps are the signing of the

International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights in October 1997, ratified in March 2001, and signing of the

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights in October 1998, which has not yet been ratified. In 2002, the PRC released a significant number of political and religious prisoners and agreed to interact with United Nations experts on torture, arbitrary detention, and religion. However, international human rights groups assert that there has been virtually no movement on these promises, with more people being arrested for similar offences since. Such groups maintain that the PRC still has a long way to go in instituting the kind of fundamental systemic change that will protect the rights and liberties of all its citizens in mainland China. The US State Department publishes an annual report on human rights around the world, which includes an evaluation of China's human rights record. In 2008, the State Department still found much to criticize about the Chinese government's human rights record, but dropped China from its list of states with the greatest human rights violations.

To counter this, China has published a White Paper annually since 1998 detailing the human rights abuses by the United States, as well as its own progress in this area.

Since October 19, 2005 the PRC government has also published a White Paper on its own democratic progress. In November 2007, the Chinese government published a White Paper on the role of Communism and other parties in China.

Influence in Asia

China's economic rise has led to some geo-political friction between the US and China in the East Asian region. For example, in response China's response to the

Bombardment of Yeonpyeong by North Korea, "Washington is moving to redefine its relationship with South Korea and Japan, potentially creating an anti-China bloc in Northeast Asia that officials say they don't want but may need." For its part, the Chinese government fears a US Encirclement Conspiracy.

In response to the increased American attacks on Pakistan during the Obama administration, the PRC has offered additional fighter jets to Pakistan.

South East Asian nations have responded to Chinese claims for sea areas by seeking closer relations with the United States. American Defense Secretary Leon Panetta has said that in spite of budget pressures, the United States will expand its influence in the region, in order to counter China's military buildup.