Illustration: Simon Bosch

"Death is nothing to be feared, Mr Brown," said the smooth-faced surgeon from the other side of the desk.

My father stiffened in his chair, grasped the armrests with bony hands and barked: "DEATH? My whole life, I have never, ever feared it."

In that moment, I swear, Dad's chair became a bevelled throne. Laurel leaves sprouted from his head and he was the mighty, wise one I have always revered.

The superhero who had dived from the banks of the fast-flowing Campaspe River to save my little brother when we all feared he would be swept away.

The gladiator who had burst from a clump of banksia roaring bloody oaths when my brothers, sister and I were cornered on a bush track in California Gully and knew we were in for a hiding by the local bullies.

It was a glimpse of the man I had always imagined would give Father Time the rigid digit. Immortal.

But then we looked again at the images on the light box on the wall in the surgeon's office and it was all too clear. We both could see the tumour.

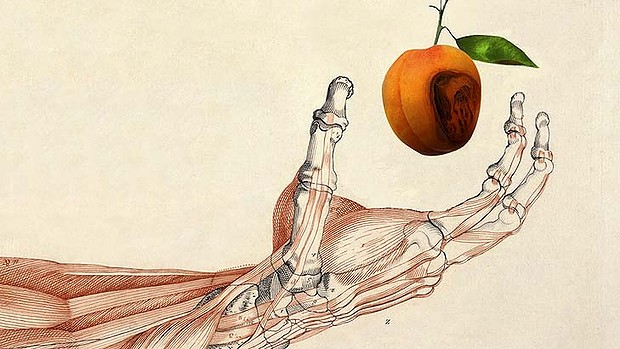

I would say it was as big as a golf ball, but Dad's always loathed golf, so instead I thought of it as the size of one of the apricots on his prized trees back in the days when he lived on the farm.

Aggressive bladder cancer. We were offered two options for treatment, neither of much use. His death will not be quick or easy.

I wished for him then, that at the age of 82, with Parko's and attendant, occasional dementia, he could tumble out of a fruit tree and die. Just like that. Deadibones! (The Big Bad Banksia Men would exult.) But, as we made our way down to the car park, not designed for anyone with a runaway walking frame, I hovered over the old man lest he should even slightly graze a knuckle.

A woman with a babe in arms rudely squeezed by us and I muttered under my breath: "This one here is just as precious as yours, lady. Equally tired and cranky." And in that moment I also knew that we - elderly father and ageing daughter - did not have right of way. Just a doddery old man and his carer. The two of us. Anonymous.

As we are constantly reminded, Australia's population is ageing. The number of Australians over 85 is expected to grow from more than 400,000 to 1.8 million by 2050.

For the first time we will have two older generations living side by side, children in their 60s and 70s and parents in their 80s and 90s.

Why are we are so slow to comprehend exactly what this means and to make provision for it?

People like my father are spoken of as "a strain on the healthcare system". It's about "expenditure", "increasing costs", a "burden" on government budgets. Not enough doctors, nurses or proper palliative care.

As everyone who has been through it knows, when you are trying to find a place in aged care for a parent, you will do a crash course as a lawyer, accountant and nurse, and be inadequate in every way.

You will encounter all manner of indignities - hearing your father being shouted at as if he were two years old; discovering him left languishing in hospital corridors or find yourself standing with him in front of broken lifts at medical centres, forming an angry mob of two.

In an odd way, looking after an ageing parent reminds me of when I had my first baby.

"Why didn't anyone tell me it would be like this?" you wail on first encountering maternity bras, tiny nail clippers and nappy rash. Babies seem to be everywhere you look. It is strange how you had never really noticed before.

It is the same with old people. Now I see they are all around, patiently being walked through shopping malls or being helped in and out of chairs.

But there's also great camaraderie to be found. Just as you could natter all day with a girlfriend who is a new mum and share stories of projectile vomit, now you also find you can happily listen to stories of catheters, bunions and X-rays. Although the difference is, of course, that every journey with an aged parent ends in death.

I suppose that is why we don't care for older Australians how we should. They remind us of our own mortality and we have to look away.

Aside from the practical frustrations, I am finding that being with my aged father is a deeply profound experience. When I see the familiar whorl of white hair on my father's bent head or hold his fragile hand, I am overcome with tenderness for him. Then comes a brusque admonition from him that reminds me I am still my father's child.

The to and fro of emotion is frightening, wounding, funny, sad. I hope Dad's gone tomorrow. I hope he lives forever.

I have not met one person of a certain age who does not have a deeply affecting tale of their parents' later years or subsequent passing. So isn't it the strangest thing that as a society we seem to be in denial about what's just up ahead?

I asked Dad what he's not looking forward to about dying.

"I don't think I'll have everything finished," he said. "I don't think I'll be ready."

Like so many of us will be, I guess, so near to death and still unprepared for its coming.

Wendy Harmer is editor in chief of The Hoopla. thehoopla.com.au