German ( ) is a West Germanic language related to and classified alongside English and Dutch. With an estimated 90 – 98 million native speakers, German is one of the world's major languages and is the most widely-spoken first language in the European Union.

Most German vocabulary is derived from the Germanic branch of the Indo-European language family. Significant minorities of words are derived from Latin and Greek, with a smaller amount from French and English.

German is written using the Latin alphabet. In addition to the 26 standard letters, German has three vowels with umlauts (Ä/ä, Ö/ö, and Ü/ü) and the letter ß.

History

Origins

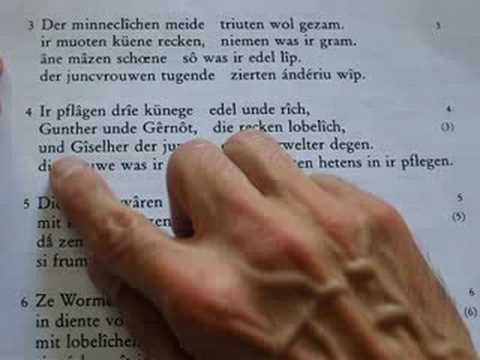

The history of the language begins with the High German consonant shift during the migration period, separating Old High German dialects from Old Saxon. The earliest testimonies of Old High German are from scattered Elder Futhark inscriptions, especially in Alemannic, from the 6th century AD; the earliest glosses (''Abrogans'') date to the 8th; and the oldest coherent texts (the ''Hildebrandslied'', the ''Muspilli'' and the Merseburg Incantations) to the 9th century. Old Saxon at this time belongs to the North Sea Germanic cultural sphere, and Low Saxon was to fall under German rather than Anglo-Frisian influence during the Holy Roman Empire.

As Germany was divided into many different states, the only force working for a unification or standardization of German during a period of several hundred years was the general preference of writers trying to write in a way that could be understood in the largest possible area.

Modern German

When

Martin Luther translated the

Bible (the

New Testament in 1522 and the

Old Testament, published in parts and completed in 1534), he based his translation mainly on the bureaucratic standard language used in Saxony (''sächsische Kanzleisprache''), also known as ''Meißner-Deutsch'' (German from the city of

Meissen). This language was based on Eastern Upper and Eastern Central German dialects and preserved much of the grammatical system of

Middle High German (unlike the spoken German dialects in Central and Upper Germany, which already at that time began to lose the

genitive case and the

preterit). In the beginning, copies of the Bible had a long list for each region, which translated words unknown in the region into the regional dialect.

Roman Catholics rejected Luther's translation in the beginning and tried to create their own Catholic standard (''gemeines Deutsch'')—which, however, differed from "Protestant German" only in some minor details. It took until the middle of the 18th century to create a standard that was widely accepted, thus ending the period of

Early New High German.

Until about 1800, standard German was almost only a written language. At this time, people in urban northern Germany, who spoke dialects very different from Standard German, learned it almost like a foreign language and tried to pronounce it as closely to the spelling as possible. Prescriptive pronunciation guides used to consider northern German pronunciation to be the standard. However, the actual pronunciation of Standard German varies from region to region.

German was the language of commerce and government in the Habsburg Empire, which encompassed a large area of Central and Eastern Europe. Until the mid-19th century it was essentially the language of townspeople throughout most of the Empire. It indicated that the speaker was a merchant, an urbanite, not their nationality. Some cities, such as Prague (German: ''Prag'') and Budapest (Buda, German: ''Ofen''), were gradually Germanized in the years after their incorporation into the Habsburg domain. Others, such as Bratislava (German: ''Pressburg''), were originally settled during the Habsburg period and were primarily German at that time. A few cities such as Milan (German: ''Mailand'') remained primarily non-German. However, most cities were primarily German during this time, such as Prague, Budapest, Bratislava, Zagreb (German: ''Agram''), and Ljubljana (German: ''Laibach''), though they were surrounded by territory that spoke other languages.

In 1901, the 2nd Orthographical Conference ended with a complete standardization of German language in its written form while the ''Deutsche Bühnensprache'' (literally, German stage language) had already established rules for German three years earlier.

Media and written works are now almost all produced in Standard German (often called ''Hochdeutsch'' in German) which is understood in all areas where German is spoken.

The first dictionary of the Brothers Grimm, the 16 parts of which were issued between 1852 and 1860, remains the most comprehensive guide to the words of the German language. In 1860, grammatical and orthographic rules first appeared in the ''Duden Handbook''. In 1901, this was declared the standard definition of the German language. Official revisions of some of these rules were not issued until 1998, when the German spelling reform of 1996 was officially promulgated by governmental representatives of all German-speaking countries. Since the reform, German spelling has been in an eight-year transitional period during which the reformed spelling is taught in most schools, while traditional and reformed spellings co-exist in the media. See German spelling reform of 1996 for an overview of the public debate concerning the reform, with some major newspapers and magazines and several known writers refusing to adopt it.

Reform of 1996

The German spelling reform of 1996 led to public controversy and considerable dispute. Some states (Bundesländer) would not accept it (

North Rhine Westphalia and

Bavaria). The dispute landed at one point in the highest court, which made a short issue of it, claiming that the states had to decide for themselves and that only in schools could the reform be made the official rule—everybody else could continue writing as they had learned it. After 10 years, without any intervention by the federal parliament, a major revision was installed in 2006, just in time for the coming school year. In 2007, some traditional spellings were finally invalidated.

The most noticeable change was probably the use of the letter ''ß'', called ''scharfes s'' or ''ess-zett'' (pronounced ''ess-tsett''). Traditionally, this letter was used in three situations: 1) after a long vowel or vowel combination, 2) before a ''t'', and 3) at the end of a syllable, thus ''Füße'', ''paßt'', and ''daß''. Currently only the first rule is in effect, thus ''Füße'', ''passt'', and ''dass''. The word ''Fuß'' 'foot' has the letter ''ß'' because it contains a long vowel, even though that letter occurs at the end of a syllable.

Geographic distribution

German-speaking communities can be found in the former German colony of Namibia, independent from South Africa since 1990, as well as in the other countries of German emigration such as the US, Canada, Mexico, Dominican Republic, Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, Chile, Peru, Venezuela (where the dialect Alemán Coloniero developed), South Africa and Australia. In Namibia, German Namibians retain German educational institutions.

According to Global Reach (2004), 6.9% of the Internet population is German. According to Netz-tipp (2002), 7.7% of webpages are written in German, making it second only to English in the European language group. They also report that 12% of Google's users use its German interface.

| Country !! German speaking population (outside Europe)

|

| |

5,000,000

|

| |

3,000,000

|

| |

500,000

|

| |

450,000 – 620,000

|

| |

200,000

|

| |

110,000

|

| |

75,000 (German expatriate citizens alone)

|

| |

60,000

|

| |

40,000

|

| |

30,000 – 40,000

|

| |

37,500

|

| |

30,000 (German expatriate citizens alone)

|

| |

10,000

|

Europe

German is primarily spoken in Germany (where it is the first language for more than 95% of the population), Austria (89%), Switzerland (65%), the majority of Luxembourg, and Liechtenstein - the latter princedom being the only state with German as only official and spoken language.

Other European German-speaking communities are found in Northern Italy (in South Tyrol and in some municipalities in other provinces), in the East Cantons of Belgium, in the French regions of Alsace and Lorraine, and in some border villages of the former South Jutland County of Denmark.

German-speaking communities can also be found in parts of the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Russia and Kazakhstan. In Russia, forced expulsions after World War II and massive emigration to Germany in the 1980s and 1990s have depopulated most of these communities.

South America

In

Brazil the largest concentrations of German speakers are in

Rio Grande do Sul (where

Riograndenser Hunsrückisch developed),

Santa Catarina,

Paraná,

São Paulo and

Espírito Santo. There are also important concentrations of German-speaking descendants in

Argentina,

Venezuela,

Paraguay and

Chile. In the 20th century, over 100,000 German

political refugees and invited entrepreneurs settled in

Latin America, in countries such as

Costa Rica,

Panama, Venezuela, and the Dominican Republic, to establish German-speaking enclaves, and reportedly there is a small

German immigration to Puerto Rico. Nearly all inhabitants of the city of

Pomerode in the state of

Santa Catarina in

Brazil can speak German. However, in most other locations where German immigrants settled, the vast majority of their descendents no longer speak German, as they have been largely assimilated into the host language and culture of the specific location of settlement; generally English in North America, and Spanish, or Portuguese in Latin America.

North America

In the United States, the states of North Dakota and South Dakota are the only states where German is the most common language spoken at home after English (the second most spoken language in other states is either Spanish or French). An indication of the German presence can be found in the names of such places as New Ulm and many other towns in Minnesota; Bismarck (state capital), Munich, Karlsruhe, and Strasburg in North Dakota; New Braunfels and Muenster in Texas; and Kiel, Berlin and Germantown in Wisconsin.

Between 1843 and 1910, more than 5 million Germans emigrated overseas, mostly to the United States. German remained an important medium for churches, schools, newspapers, and even the administration of the United States Brewers' Association through the early 20th century, but was severely repressed during World War I. Over the course of the 20th century many of the descendants of 18th century and 19th century immigrants ceased speaking German at home, but small populations of elderly (as well as some younger) speakers can be found in Pennsylvania (Amish, Hutterites, Dunkards and some Mennonites historically spoke Hutterite German and a West Central German variety of German known as Pennsylvania Dutch), Kansas (Mennonites and Volga Germans), North Dakota (Hutterite Germans, Mennonites, Russian Germans, Volga Germans, and Baltic Germans), South Dakota, Montana, Texas (Texas German), Wisconsin, Indiana, Oregon, Louisiana and Oklahoma. A significant group of German Pietists in Iowa formed the Amana Colonies and continue to practice speaking their heritage language. Early twentieth century immigration was often to St. Louis, Chicago, New York, Milwaukee, Pittsburgh and Cincinnati.

In Canada, there are 622,650 speakers of German according to the most recent census in 2006, while people of German ancestry (German Canadians) are found throughout the country. German-speaking communities are particularly found in British Columbia (118,035) and Ontario (230,330). There is a large and vibrant community in the city of Kitchener, Ontario, which was at one point named Berlin. German immigrants were instrumental in the country's three largest urban areas: Montreal, Toronto, and Vancouver; while post-Second World War immigrants managed to preserve a fluency in the German language in their respective neighborhoods and sections. In the first half of the 20ᵗʰ century, over a million German-Canadians made the language Canada's third most spoken after French and English.

In Mexico there are also large populations of German ancestry, mainly in the cities of: Mexico City, Puebla, Mazatlán, Tapachula, Ecatepec de Morelos, and larger populations scattered in the states of Chihuahua, Durango, and Zacatecas. German ancestry is also said to be found in neighboring towns around Guadalajara, Jalisco and much of Northern Mexico, where German influence was immersed into the Mexican culture. Standard German is spoken by the affluent German communities in Puebla, Mexico City, Nuevo León, San Luis Potosí and Quintana Roo.

The dialects of German which are or were primarily spoken in colonies or communities founded by German-speaking people resemble the dialects of the regions the founders came from. For example, Pennsylvania German resembles Palatinate German dialects, and Hutterite German resembles dialects of Carinthia. Texas German is a dialect spoken in the areas of Texas settled by the Adelsverein, such as New Braunfels and Fredericksburg. In the Amana Colonies in the state of Iowa, Amana German is spoken. Plautdietsch is a large minority language spoken in Northern Mexico by the Mennonite communities, and is spoken by more than 200,000 people in Mexico. Pennsylvania Dutch is a dialect of German spoken by the Amish population of Pennsylvania, Indiana, and Ohio.

Hutterite German is an Upper German dialect of the Austro-Bavarian variety of the German language, which is spoken by Hutterite communities in Canada and the United States. Hutterite is spoken in the U.S. states of Washington, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Minnesota; and in the Canadian provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba. Its speakers belong to some Schmiedleit, Lehrerleit, and Dariusleit Hutterite groups, but there are also speakers among the older generations of Prairieleit (the descendants of those Hutterites who chose not to settle in colonies). Hutterite children who grow up in the colonies learn to speak Hutterite German before learning English, the standard language of the surrounding areas, in school. Many of these children, though, continue with German Grammar School, in addition to public school, throughout a student's elementary education.

Australia

In

Australia, the state of

South Australia experienced a pronounced wave of immigration in the 1840s from Prussia (particularly the

Silesia region). With the prolonged isolation from other German speakers and contact with

Australian English some have suggested a unique dialect formed known as

Barossa German spoken predominantly in the

Barossa Valley near

Adelaide. Usage sharply declined with the advent of

World War I, due to the prevailing anti-German sentiment in the population and related government action. It continued to be used as a first language into the twentieth century but now its use is limited to a few older speakers.

New Zealand

German migration to New Zealand in the nineteenth century was less pronounced then migration from the British and Irish Isles and perhaps even Scandinavia. Despite this there were significant pockets of German speaking communities lasting up to the first decades of the twentieth century. German-speakers settled principally in Puhoi, Nelson and Gore. Puhoi was settled by Bohemians and these settlers retained the Egerlaender dialect long after it died out in its native land. At last estimate a few dozen inhabitants still speak this dialect fluently.

At the last census (2006) 37,500 people in New Zealand spoke German. This made German the third most spoken European language after English and French and the ninth most spoken language over all. German is somewhat of an invisble minority language, however, as most speakers, other than the very young, are fluent in English. Unlike less widely spoken languages (for example Korean, Nuiean or Cook Island Maori) government departments make no provision for German speakers to communicate with them in the language.

Asia

There is also an important German

creole being studied and recovered, named

Unserdeutsch, spoken in the former German colony of

Papua New Guinea, across

Micronesia and in northern Australia (i.e. coastal parts of

Queensland and

Western Australia), by a few elderly people. The risk of its extinction is serious and efforts to revive interest in the language are being implemented by scholars.

Standard German

Standard German originated not as a traditional dialect of a specific region, but as a

written language. However, there are places where the traditional regional dialects have been replaced by standard German; this is the case in vast stretches of

Northern Germany, but also in major cities in other parts of the country.

Standard German differs regionally, between German-speaking countries, in vocabulary and some instances of pronunciation, and even grammar and orthography. This variation must not be confused with the variation of local dialects . Even though the regional varieties of standard German are only to a certain degree influenced by the local dialects, they are very distinct. German is thus considered a pluricentric language.

In most regions, the speakers use a continuum of mixtures from more dialectal varieties to more standard varieties according to situation.

In the German-speaking parts of Switzerland, mixtures of dialect and standard are very seldom used, and the use of standard German is largely restricted to the written language. Therefore, this situation has been called a ''medial diglossia''. Swiss Standard German is used in the Swiss, Austrian Standard German officially in the Austrian education system.

Official status

Standard German is the only

official language in Liechtenstein; it shares official status in

Germany (with

Danish,

Frisian,

Romany and

Sorbian as minority languages), in Austria (with

Slovene,

Croatian, and

Hungarian as minority languages), Switzerland (with

French,

Italian and

Romansh), Belgium (with

Dutch (

Flemish) and French) and Luxembourg (with French and

Luxembourgish). It is used as an official regional language in Italy (

South Tyrol), as well as in the cities of

Sopron (Hungary), Krahule (

Slovakia) and several cities in Romania. It is the official command language (with Italian) of the

Vatican Swiss Guard.

German has an officially recognized status as regional or auxiliary language in Denmark (South Jutland region), Italy (Gressoney valley), Namibia, Poland (Opole region), and Russia (Asowo and Halbstadt).

German is one of the 23 official languages of the European Union. It is the language with the largest number of native speakers in the European Union, and is the second-most spoken language in Europe, just behind English and ahead of French.

German as a foreign language

German is the third-most taught foreign language in the English-speaking world, after French and Spanish.

German is the main language of about 90 – 98 million million people in Europe (as of 2004), or 13.3% of all Europeans, being the second most spoken native language in Europe after Russian, above French (66.5 million speakers in 2004) and English (64.2 million speakers in 2004). It is therefore the most spoken first language in the EU. It is the second most known foreign language in the EU. It is one of the official languages of the European Union, and one of the three working languages of the European Commission, along with English and French. Thirty-two percent of citizens of the EU-15 countries say they can converse in German (either as a mother tongue or as a second or foreign language). This is assisted by the widespread availability of German TV by cable or satellite.

Dialects

German is a member of the western branch of the Germanic family of languages, which in turn is part of the Indo-European language family. The German dialect continuum is traditionally divided most broadly into High German and Low German.

The variation among the German dialects is considerable, with only the neighboring dialects being mutually intelligible. Some dialects are not intelligible to people who only know standard German. However, all German dialects belong to the dialect continuum of High German and Low Saxon languages.

Low German

Middle Low German was the lingua franca of the Hanseatic League. It was the predominant language in Northern Germany. This changed in the 16th century, when in 1534 the Luther Bible by Martin Luther was printed. This translation is considered to be an important step towards the evolution of the Early New High German. It aimed to be understandable to a broad audience and was based mainly on Central and Upper German varieties. The Early New High German language gained more prestige than Low German and became the language of science and literature. Other factors were that around the same time, the Hanseatic league lost its importance as new trade routes to Asia and the Americas were established, and that the most powerful German states of that period were located in Middle and Southern Germany.

The 18th and 19th centuries were marked by mass education of Standard German in schools. Slowly, Low German was politically viewed as nothing but a dialect language spoken by the uneducated. Today Low Saxon can be divided in two groups: Low Saxon varieties with a reasonable standard German influx and varieties of Standard German with a Low Saxon influence known as Missingsch. Sometimes, Low Saxon and Low Franconian varieties are grouped together because both are unaffected by the High German consonant shift. However, the part of the population capable of speaking and responding to it, or of understanding it has decreased continuously since World War II.

High German

High German is divided into Central German, High Franconian (a transitional dialect), and Upper German. Central German dialects include Ripuarian, Moselle Franconian, Rhine Franconian, Central Hessian, East Hessian, North Hessian, Thuringian, Silesian German, Lorraine Franconian, Mittelalemannisch, North Upper Saxon, High Prussian, Lausitzisch-Neumärkisch and Upper Saxon. It is spoken in the southeastern Netherlands, eastern Belgium, Luxembourg, parts of France, and parts of Germany approximately between the River Main and the southern edge of the Lowlands. Modern Standard German is mostly based on Central German, but it should be noted that the common (but not linguistically correct) German term for modern Standard German is ''Hochdeutsch'', that is, ''High German''.

The Moselle Franconian varieties spoken in Luxembourg have been officially standardised and institutionalised and are therefore usually considered a separate language known as Luxembourgish.

The two High Franconian dialects are East Franconian and South Franconian.

Upper German dialects include Northern Austro-Bavarian, Central Austro-Bavarian,

Southern Austro-Bavarian, Swabian, East Franconian, High Alemannic German, Highest Alemannic German, Alsatian and Low Alemannic German. They are spoken in parts of the Alsace, southern Germany, Liechtenstein, Austria, and the German-speaking parts of Switzerland and Italy.

Vilamovian is a High German dialect of Poland, and Sathmarisch and Siebenbürgisch are High German dialects of Romania. The High German varieties spoken by Ashkenazi Jews (mostly in the former Soviet Union) have several unique features, and are usually considered as a separate language, Yiddish. It is the only Germanic language that does not use the Latin script as the basis of its standard alphabet.

Varieties of standard German

In German

linguistics, German

dialects are distinguished from

varieties of

standard German.

The ''German dialects'' are the traditional local varieties. They are traditionally traced back to the different German tribes. Many of them are hardly understandable to someone who knows only standard German, since they often differ from standard German in lexicon, phonology and syntax. If a narrow definition of language based on mutual intelligibility is used, many German dialects are considered to be separate languages (for instance in the Ethnologue). However, such a point of view is unusual in German linguistics.

The ''varieties of standard German'' refer to the different local varieties of the pluricentric standard German. They only differ slightly in lexicon and phonology. In certain regions, they have replaced the traditional German dialects, especially in Northern Germany.

Grammar

German is an inflected language with three grammatical genders; as such, there can be a large number of words derived from the same root.

Noun inflection

German nouns inflect into:

one of four cases: nominative, genitive, dative, and accusative.

one of three genders: masculine, feminine, or neuter. Word endings sometimes reveal grammatical gender; for instance, nouns ending in ''...ung'' (ing), ''...schaft'' (-ship), ''...keit'' or ''...heit'' (-hood) are feminine, while nouns ending in ''...chen'' or ''...lein'' (diminutive forms) are neuter and nouns ending in ''...ismus'' (-ism) are masculine. Others are controversial, sometimes depending on the region in which it is spoken. Additionally, ambiguous endings exist, such as ''...er'' (-er), e.g. ''Feier (feminine)'', Eng. ''celebration, party'', ''Arbeiter (masculine)'', Eng. labourer, and ''Gewitter (neuter)'', Eng. thunderstorm.

two numbers: singular and plural

Although German is usually cited as an outstanding example of a highly inflected language, the degree of inflection is considerably less than in Old High German or in other old Indo-European languages such as Latin, Ancient Greek, or Sanskrit, or, for instance, in modern Icelandic or Russian. The three genders have collapsed in the plural, which now behaves, grammatically, somewhat as a fourth gender. With four cases and three genders plus plural there are 16 distinct possible combinations of case and gender/number, but presently there are only six forms of the definite article used for the 16 possibilities. Inflection for case on the noun itself is required in the singular for strong masculine and neuter nouns in the genitive and sometimes in the dative. Both of these cases are losing way to substitutes in informal speech. The dative ending is considered somewhat old-fashioned in many contexts and often dropped, but it is still used in sayings and in formal speech or in written language. Weak masculine nouns share a common case ending for genitive, dative and accusative in the singular. Feminines are not declined in the singular. The plural does have an inflection for the dative. In total, seven inflectional endings (not counting plural markers) exist in German: ''-s, -es, -n, -ns, -en, -ens, -e''.

In the German orthography, nouns and most words with the syntactical function of nouns are capitalised, which is supposed to make it easier for readers to find out what function a word has within the sentence (''Am Freitag ging ich einkaufen.''—"On Friday I went shopping."; ''Eines Tages kreuzte er endlich auf.''—"One day he finally showed up.") This convention is almost unique to German today (shared perhaps only by the closely related Luxemburgish language and several insular dialects of the North Frisian language), although it was historically common in other languages such as Danish and English.

Like most Germanic languages, German forms noun compounds where the first noun modifies the category given by the second, for example: ''Hundehütte'' (Eng. ''dog hut''; specifically: ''doghouse''). Unlike English, where newer compounds or combinations of longer nouns are often written in ''open'' form with separating spaces, German (like the other German languages) nearly always uses the ''closed'' form without spaces, for example: Baumhaus (Eng. ''tree house''). Like English, German allows arbitrarily long compounds, but these are rare. (''See also'' English compounds.)

The longest German word verified to be actually in (albeit very limited) use is Rindfleischetikettierungsüberwachungsaufgabenübertragungsgesetz, which, literally translated, is "beef labelling supervision duty assignment law" [from Rind (cattle), Fleisch (meat), Etikettierung(s) (labelling), Überwachung(s) (supervision), Aufgaben (duties), Übertragung(s) (assignment), Gesetz (law)].

Verb inflection

Standard German verbs inflect into:

one of primarily two conjugation classes: weak and strong (as in English). Additionally, there is a third class, known as mixed verbs, which exhibit inflections combining features of both the strong and weak patterns.

three persons: 1st, 2nd, 3rd.

two numbers: singular and plural

three moods: indicative, imperative, subjunctive

two voices: active and passive; the passive being composed and dividable into static and dynamic.

two non-composed tenses (present, preterite) and four composed tenses (perfect, pluperfect, future and future perfect)

distinction between grammatical aspects is rendered by combined use of subjunctive and/or preterite marking; thus: neither of both is plain indicative voice, sole subjunctive conveys second-hand information, subjunctive plus preterite marking forms the conditional state, and sole preterite is either plain indicative (in the past), or functions as a (literal) alternative for either second-hand-information or the conditional state of the verb, when one of them may seem indistinguishable otherwise.

distinction between perfect and progressive aspect is and has at every stage of development been at hand as a productive category of the older language and in nearly all documented dialects, but, strangely enough, is nowadays rigorously excluded from written usage in its present normalised form.

disambiguation of completed vs. uncompleted forms is widely observed and regularly generated by common prefixes (blicken - to look, erblicken - to see [unrelated form: sehen - to see]).

;Verb prefixes

The meaning of base verbs can be expanded, and sometimes radically changed, through the use of any number of prefixes. Some prefixes have a meaning themselves; the prefix ''zer-'' refers to the destruction of things, as in ''zerreißen'' (to tear apart), ''zerbrechen'' (to break apart), ''zerschneiden'' (to cut apart). Others do not have more than the vaguest meaning in and of themselves; the use of ''ver-'' is found in a number of verbs with a large variety of meanings, as in ''versuchen'' (to try), ''vernehmen'' (to interrogate), ''verteilen'' (to distribute), ''verstehen'' (to understand).

Other examples include ''haften'' (to stick), ''verhaften'' (to detain); ''kaufen'' (to buy), ''verkaufen'' (to sell); ''hören'' (to hear), ''aufhören'' (to cease); ''fahren'' (to drive), ''erfahren'' (to experience).

Many German verbs have a separable prefix, often with an adverbial function. In finite verb forms this is split off and moved to the end of the clause, and is hence considered by some to be a "resultative particle". For example, ''mitgehen'' meaning "to go along" would be split, giving ''Gehen Sie mit?'' (Literal: "Go you with?" ; Formal: "Are you going along?").

Indeed, several parenthetical clauses may occur between the prefix of a finite verb and its complement; e.g.

:''Er kam am Freitagabend nach einem harten Arbeitstag und dem üblichen Ärger, der ihn schon seit Jahren immer wieder an seinem Arbeitsplatz plagt, mit fraglicher Freude auf ein Mahl, das seine Frau ihm, wie er hoffte, bereits aufgetischt hatte, endlich zu Hause an ''.

A literal translation of this example might look like this:

:He -rived on Friday evening, after a hard day at work and the usual annoyances that had been repeatedly troubling him for years now at his workplace, with questionable joy, to a meal which, as he hoped, his wife had already served him, finally at home ar-.

Word order

Word order is generally less rigid than in Modern English. There are two common

word orders: one is for main

clauses and another for

subordinate clauses. In normal affirmative sentences the ''inflected'' verb always has position 2. In polar questions, exclamations, and wishes it always has position 1. In subordinate clauses the verb is supposed to occur at the very end, but in speech this rule is often disregarded.

German requires that a verbal element (main verb or auxiliary verb) appear second in the sentence. The verb is preceded by the topic of the sentence. The element in focus appears at the end of the sentence. For a sentence without an auxiliary this gives, amongst other options:

: '''' (The old man gave me yesterday the book; normal order)

: '''' (The book gave [to] me yesterday the old man)

: '''' (The book gave the old man [to] me yesterday)

: '''' (Yesterday gave [to] me the old man the book, normal order)

: '''' ([To] me gave the old man the book yesterday (entailing: as for you, it was another date))

The position of a noun in a German sentence has no bearing on its being a subject, an object, or another argument. In a declarative sentence in English if the subject does not occur before the predicate the sentence could well be misunderstood. This is not the case in German.

;Auxiliary verbs

When an auxiliary verb is present, the auxiliary appears in second position, and the main verb appears at the end. This occurs notably in the creation of the perfect. Many word orders are still possible, e.g.:

:'''' (The old man has given me the book today.)

:'''' (The book has the old man given me today.)

:'''' (Today the old man has given me the book.)

;Modal verbs

Sentences using modal verbs place the infinitive at the end. For example, the sentence in Modern English "Should he go home?" would be rearranged in German to say "Should he (to) home go?" (''''). Thus in sentences with several subordinate or relative clauses the infinitives are clustered at the end. Compare the similar clustering of prepositions in the following English sentence: "What did you bring that book which I don't like to be read to out of up for?"

;Multiple infinitives

German subordinate clauses have all verbs clustered at the end. Given that auxiliaries encode future, passive, modality, and the perfect, this can lead to very long chains of verbs at the end of the sentence. In these constructions, the past participle in ''ge-'' is often replaced by the infinitive.

''Man nimmt an, dass der Deserteur wohl erschossenV wordenpsv seinperf solltemod''

One suspects that the deserter probably shot become be should

("It is suspected that the deserter probably should have been shot")

The order at the end of such strings is subject to variation, though the latter version is unusual.

''Er wusste nicht, dass der Agent einen Nachschlüssel hatte machen lassen''

He knew not that the agent a picklock had make let

''Er wusste nicht, dass der Agent einen Nachschlüssel machen lassen hatte''

He knew not that the agent a picklock make let had

("He did not know that the agent had had a picklock made")

Vocabulary

Most German vocabulary is derived from the Germanic branch of the Indo-European language family, although there are significant minorities of words derived from Latin and Greek, and a smaller amount from French and most recently English. At the same time, the effectiveness of the German language in forming equivalents for foreign words from its inherited Germanic stem repertory is great. Thus, Notker Labeo was able to translate Aristotelian treatises in pure (Old High) German in the decades after the year 1000. Overall, German has fewer Romance-language loanwords than English or even Dutch.

Even today, some low-key non-academic movements try to promote the ''Ersatz'' (substitution) of virtually all foreign words with ancient, dialectal, or neologous German alternatives. It is claimed that this would also help in spreading modern or scientific notions among the less educated, and thus democratise public life, too.

The modern German scientific vocabulary has nine million words and word groups (based on the analysis of 35 million sentences of a corpus in Leipzig, which as of July 2003 included 500 million words in total).

Literature

The German language is used in German literature and can be traced back to the Middle Ages, with the most notable authors of the period being Walther von der Vogelweide and Wolfram von Eschenbach.

The ''Nibelungenlied'', whose author remains unknown, is also an important work of the epoch, as is the ''Thidrekssaga''. The fairy tales collections collected and published by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm in the 19th century became famous throughout the world.

Theologian Luther, who translated the Bible into German, is widely credited for having set the basis for the modern "High German" language. Among the most well known German poets and authors are Lessing, Goethe, Schiller, Kleist, Hoffmann, Brecht, Heine and Schmidt. Thirteen German speaking people have won the Nobel Prize in literature: Theodor Mommsen, Rudolf Christoph Eucken, Paul von Heyse, Gerhart Hauptmann, Carl Spitteler, Thomas Mann, Nelly Sachs, Hermann Hesse, Heinrich Böll, Elias Canetti, Günter Grass, Elfriede Jelinek and Herta Müller.

Orthography

German is written in the Latin alphabet. In addition to the 26 standard letters, German has three vowels with Umlaut, namely ''ä'', ''ö'' and ''ü'', as well as the Eszett or ''scharfes s'' (sharp s), ''ß''.

Written texts in German are easily recognisable as such by distinguishing features such as umlauts and certain orthographical features—German is the only major language that capitalizes all nouns—and the frequent occurrence of long compounds (the longest German word is made of 79 characters).

Present

Before the

German spelling reform of 1996, ''ß'' replaced ''ss'' after

long vowels and diphthongs and before consonants, word-, or partial-word-endings. In reformed spelling, ''ß'' replaces ''ss'' only after long vowels and diphthongs. Since there is no

capital ß, it is always written as SS when capitalization is required. For example, ''Maßband'' (tape measure) is capitalized ''MASSBAND''. An exception is the use of ß in legal documents and forms when capitalizing names. To avoid confusion with similar names, a "ß" is to be used instead of "SS". (So: "KREßLEIN" instead of "KRESSLEIN".) A

capital ß has been proposed and included in

Unicode, but it is not yet recognized as standard German. In

Switzerland, ß is not used at all.

Umlaut vowels (ä, ö, ü) are commonly transcribed with ae, oe, and ue if the umlauts are not available on the keyboard used. In the same manner ß can be transcribed as ss. Some operating systems use key sequences to extend the set of possible characters to include, amongst other things, umlauts; in Microsoft Windows this is done using Alt codes. German readers understand those transcriptions (although they look unusual), but they are avoided if the regular umlauts are available because they are considered a makeshift, not proper spelling. (In Westphalia and Schleswig-Holstein, city and family names exist where the extra e has a vowel lengthening effect, e.g. ''Raesfeld'' , ''Coesfeld'' and ''Itzehoe'' , but this use of the letter e after a/o/u does not occur in the present-day spelling of words other than proper nouns.)

There is no general agreement on where these umlauts occur in the sorting sequence. Telephone directories treat them by replacing them with the base vowel followed by an e. Some dictionaries sort each umlauted vowel as a separate letter after the base vowel, but more commonly words with umlauts are ordered immediately after the same word without umlauts. As an example in a telephone book ''Ärzte'' occurs after '''' but before ''Anlagenbauer'' (because Ä is replaced by Ae). In a dictionary ''Ärzte'' comes after ''Arzt'', but in some dictionaries ''Ärzte'' and all other words starting with "Ä" may occur after all words starting with "A". In some older dictionaries or indexes, initial ''Sch'' and ''St'' are treated as separate letters and are listed as separate entries after ''S'', but they are usually treated as S+C+H and S+T.

Written German also typically uses an alternative opening inverted comma (quotation mark) as in „''Guten Morgen''!”.

Past

Until the early twentieth century, German was mostly printed in

blackletter typefaces (mostly in

Fraktur, but also in

Schwabacher) and written in corresponding

handwriting (for example

Kurrent and

Sütterlin). These variants of the Latin alphabet are very different from the serif or

sans serif Antiqua typefaces used today, and particularly the handwritten forms are difficult for the untrained to read. The printed forms however were claimed by some to be actually more readable when used for printing

Germanic languages. The

Nazis initially promoted Fraktur and Schwabacher since they were considered

Aryan, although they later abolished them in 1941 by claiming that these letters were Jewish. The Fraktur script remains present in everyday life through road signs, pub signs, beer brands and other forms of advertisement, where it is used to convey a certain rusticality and oldness.

A proper use of the long s, (''langes s''), ſ, is essential to write German text in Fraktur typefaces. Many Antiqua typefaces include the long s, also. A specific set of rules applies for the use of long s in German text, but it is rarely used in Antiqua typesetting, recently. Any lower case "s" at the beginning of a syllable would be a long s, as opposed to a terminal s or short s (the more common variation of the letter s), which marks the end of a syllable; for example, in differentiating between the words ''Wachſtube'' (=guard-house) and ''Wachstube'' (=tube of floor polish). One can decide which "s" to use by appropriate hyphenation, easily ("Wach-ſtube" vs. "Wachs-tube"). The long s only appears in lower case.

Phonology

Vowels

German vowels (excluding diphthongs; see below) come in ''short'' and ''long'' varieties, as detailed in the following table:

| !! A !! Ä !! E !! I !! O !! Ö !! U !! Ü

|

| ! short

|

|

|

| | |

|

|

|

|

| long

| |

|

| | |

|

|

|

|

Short is realized as in stressed syllables (including

secondary stress), but as in unstressed syllables. Note that stressed short can be spelled either with ''e'' or with ''ä'' (''hätte'' 'would have' and ''Kette'' 'chain', for instance, rhyme). In general, the short vowels are open and the long vowels are closed. The one exception is the open sound of long Ä; in some varieties of standard German, and have merged into , removing this anomaly. In that case, pairs like ''Bären/Beeren'' 'bears/berries' or ''Ähre/Ehre'' 'spike (of wheat)/honour' become homophonous.

In many varieties of standard German, an unstressed is not pronounced , but vocalised to .

Whether any particular vowel letter represents the long or short phoneme is not completely predictable, although the following regularities exist:

If a vowel (other than ''i'') is at the end of a syllable or followed by a single consonant, it is usually pronounced long (e.g. ''Hof'' ).

If the vowel is followed by a double consonant (e.g. ''ff'', ''ss'' or ''tt''), ''ck'', ''tz'' or a consonant cluster (e.g. ''st'' or ''nd''), it is nearly always short (e.g. ''hoffen'' ). Double consonants are used only for this function of marking preceding vowels as short; the consonant itself is never pronounced lengthened or doubled, in other words this is not a feeding order of gemination and then vowel shortening.

Both of these rules have exceptions (e.g. ''hat'' 'has' is short despite the first rule; ''Mond'' , 'moon' is long despite the second rule). For an ''i'' that is neither in the combination ''ie'' (making it long) nor followed by a double consonant or cluster (making it short), there is no general rule. In some cases, there are regional differences: In central Germany (Hessen), the ''o'' in the proper name "Hoffmann" is pronounced long while most other Germans would pronounce it short; the same applies to the ''e'' in the geographical name "Mecklenburg" for people in that region. The word ''Städte'' 'cities', is pronounced with a short vowel by some (Jan Hofer, ARD Television) and with a long vowel by others (Marietta Slomka, ZDF Television). Finally, a vowel followed by ''ch'' can be short (''Fach'' 'compartment', ''Küche'' 'kitchen') or long (''Suche'' 'search', ''Bücher'' 'books') almost at random. Thus, ''Lache'' is homographous: (Lache) 'puddle' and (lache) 'manner of laughing' (coll.), 'laugh!' (Imp.).

German vowels can form the following digraphs (in writing) and diphthongs (in pronunciation); note that the pronunciation of some of them (ei, äu, eu) is very different from what one would expect when considering the component letters:

| spelling

| ai, ei, ay, ey |

au |

äu, eu

|

| pronunciation

| |

|

|

Additionally, the digraph ''ie'' generally represents the phoneme , which is not a diphthong. In many varieties, an at the end of a syllable is vocalised. However, a sequence of a vowel followed by such a vocalised is not considered a diphthong: Bär 'bear', er 'he', wir 'we', Tor 'gate', kurz 'short', Wörter 'words'.

In most varieties of standard German, syllables that begin with a vowel are preceded by a glottal stop .

Consonants

With approximately 25 phonemes, the German consonant system exhibits an average number of consonants in comparison with other languages. One of the more noteworthy ones is the unusual

affricate . The consonant inventory of the standard language is shown below.

| !

|

Bilabial consonant>Bilabial

|

Labiodental consonant>Labiodental

|

Alveolar consonant>Alveolar

|

Postalveolar consonant>Postalveolar

|

Palatal consonant>Palatal

|

Velar consonant>Velar

|

Uvular consonant>Uvular

|

Glottal consonant>Glottal

|

| Plosive consonant>Plosive

|

3 4

|

|

3 4

|

|

|

3 4

|

|

|

| Affricate consonant>Affricate

|

|

|

|

()5

|

|

|

|

|

| Fricative consonant>Fricative

|

|

|

|

()5

|

|

1

|

|

|

| Nasal stop>Nasal

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Approximant consonant>Approximant

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Rhotic consonant>Rhotic

|

|

|

2

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 has two allophones, and , after back and front vowels, respectively.

2 has three allophones in free variation: , and . In the syllable coda, the allophone is found in many varieties.

3 The voiceless stops , , are aspirated except when preceded by a sibilant.

4 The voiced stops , , are devoiced to , , , respectively, in word-final position.

5 and occur only in words of foreign origin.

Where a stressed syllable has an initial vowel, it is preceded by . As its presence is predictable from context, is not considered a phoneme.

;Consonant spellings

c standing by itself is not a German letter. In borrowed words, it is usually pronounced (before ä, äu, e, i, ö, ü, y) or (before a, o, u, and consonants). The combination ck is, as in English, used to indicate that the preceding vowel is short.

ch occurs most often and is pronounced either (after ä, ai, äu, e, ei, eu, i, ö, ü and consonants; in the diminutive suffix -chen; and at the beginning of a word), (after a, au, o, u), or at the beginning of a word before a, o, u and consonants. Ch never occurs at the beginning of an originally German word. In borrowed words with initial Ch before bright vowels (''Chemie'' "chemistry" etc.), is considered standard, but is itself practically absent from language in use. Upper Germans and Franconians (in the popular, not linguistic sense) will replace them with , as German as a whole does before darker vowels and consonants such as in ''Charakter'', ''Christentum''. Middle Germans (saving Franconians) will borrow a from the French model. Both agree in considering each other's variant, and Upper Germans also the standard in , as particularly awkward and unusual.

dsch is pronounced (like ''j'' in ''Jungle'') but appears in a few loanwords only.

f is pronounced as in "''f''ather".

h is pronounced as in "''h''ome" at the beginning of a syllable. After a vowel it is silent and only lengthens the vowel (e.g. ''Reh'' = roe deer).

j is pronounced in Germanic words (''Jahr'' ). In younger loanwords, it follows more or less the respective languages' pronunciations.

l is always pronounced , never (the English "dark L").

q only exists in combination with u and appears in both Germanic and Latin words (''quer''; ''Qualität''). The digraph qu is pronounced .

r is usually pronounced in a guttural fashion (a voiced uvular fricative or uvular trill ) in front of a vowel or consonant (''Rasen'' ; ''Burg'' ). In spoken German, however, it is commonly vocalised after a vowel (''er'' being pronounced rather like —''Burg'' ). In some varieties, the r is pronounced as a "tongue-tip" ''r'' (the alveolar trill ).

s in Germany, is pronounced (as in "''z''ebra") if it forms the syllable onset (e.g. ''Sohn'' ), otherwise (e.g. ''Bus'' ). In Austria and Switzerland, it is always pronounced . A ss indicates that the preceding vowel is short. st and sp at the beginning of words of German origin are pronounced and , respectively.

ß (a letter unique to German called ''scharfes S'' or ''Eszett'') was a ligature of a double s ''and'' of an sz and is always pronounced . Originating in Blackletter typeface, it traditionally replaced ss at the end of a syllable (e.g. ''ich muss'' → ''ich muß''; ''ich müsste'' → ''ich müßte''); within a word it contrasts with ss in indicating that the preceding vowel is long (compare ''in Maßen'' "with moderation" and ''in Massen'' "in loads"). The use of ß has recently been limited by the latest German spelling reform and is no longer used for ss after a short vowel (e.g. "ich muß" and "ich müßte" were always pronounced with a short U/Ü); Switzerland and Liechtenstein already abolished it in 1934.

sch is pronounced (like "sh" in "shine").

tion in Latin loanwords is pronounced .

v is pronounced in words of Germanic origin, to wit, ''Vater'' , ''Vogel'' "bird", ''von'' "from, of", ''vor'' "before, in front of", ''voll'' "full" (yet "to fill" is notwithstandingly spelt ''füllen'') and the prefix ''ver-''. It is also used in loanwords, where it is supposed to be pronounced . This pronunciation is retained for example in ''Vase'', ''Vikar'', ''Viktor'', ''Viper'', ''Ventil'', ''vulgär'', and English loanwords; however, pronunciation tends to the further you travel south. They have reached a plain ''f'' in Bavaria and Swabia.

w is pronounced as in "''v''acation" (e.g. ''was'' ).

y only appears in loanwords and is traditionally considered a vowel.

z is always pronounced (e.g. ''zog'' ). A

tz indicates that the preceding vowel is short.

Consonant shifts

German does not have any dental fricatives (as English th). The th sounds, which the English language still has, survived on the continent up to Old High German and then disappeared in German with the consonant shifts between the 8th and the 10th centuries. It is sometimes possible to find parallels between English and German by replacing the English th with d in German: "Thank" → in German "Dank", "this" and "that" → "dies" and "das", "thou" (old 2nd person singular pronoun) → "du", "think" → "denken", "thirsty" → "durstig" and many other examples.

Likewise, the gh in Germanic English words, pronounced in several different ways in modern English (as an f, or not at all), can often be linked to German ch: "to laugh" → "lachen", "through" and "thorough" → "durch", "high" → "hoch", "naught" → "nichts", "light" → "leicht", "sight" → "Sicht" etc.

Loanwords

English has taken many

loanwords from German, often without any change of spelling:

Organisations

The use and learning of the German language are promoted by a number of organisations.

Goethe Institut

The government-backed Goethe Institut (named after the famous German author Johann Wolfgang von Goethe) aims to enhance the knowledge of German culture and language within Europe and the rest of the world. This is done by holding exhibitions and conferences with German-related themes, and providing training and guidance in the learning and use of the German language. For example the Goethe Institut teaches the Goethe-Zertifikat German language qualification.

Deutsche Welle

The German state broadcaster

Deutsche Welle is the equivalent of the British

BBC World Service and provides radio and television broadcasts in German and a 30 other languages across the globe. Its German language services are tailored for German language learners by being spoken at slow speed. Deutsche Welle also provides an E-learning website to learn German.

See also

References

Bibliography

Fausto Cercignani, ''The Consonants of German: Synchrony and Diachrony'', Milano, Cisalpino, 1979.

Michael Clyne, ''The German Language in a Changing Europe'' (1995) ISBN 0521499704

George O. Curme, ''A Grammar of the German Language'' (1904, 1922)—the most complete and authoritative work in English

Anthony Fox, ''The Structure of German'' (2005) ISBN 0199273995

W.B. Lockwood, ''German Today: The Advanced Learner's Guide'' (1987) ISBN 0198158505

Ruth H. Sanders. ''German: Biography of a Language'' (Oxford University Press; 2010) 240 pages. Combines linguistic, anthropological, and historical perspectives in a "biography" of German in terms of six "signal events" over millennia, including the Battle of Kalkriese, which blocked the spread of Latin-based language north.

External links

German vocabulary: German language vocabulary resource.

The Goethe Institute: German Government sponsored organisation for the promotion of the German language and culture.

USA Foreign Service Institute German basic course

German phrasebook at Wikitravel

Category:Fusional languages

Category:High German languages

Category:Languages of Austria

Category:Languages of Belgium

Category:Languages of Brazil

Category:Languages of Denmark

Category:Languages of France

Category:Languages of Germany

Category:Languages of Hungary

Category:Languages of Kazakhstan

Category:Languages of Liechtenstein

Category:Languages of Luxembourg

Category:Languages of Namibia

Category:Languages of Romania

Category:Languages of Russia

Category:Languages of Switzerland

Category:Languages of Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol

Category:Stress-timed languages

Category:Subject–object–verb languages

Category:Verb-second languages

kbd:Джэрмэныбзэ

af:Duits

als:Deutsche Sprache

am:ጀርመንኛ

ang:Þēodsc sprǣc

ab:Алман бызшәа

ar:لغة ألمانية

an:Idioma alemán

arc:ܠܫܢܐ ܓܪܡܢܝܐ

frp:Alemand

ast:Idioma Alemán

ay:Aliman aru

az:Alman dili

bn:জার্মান ভাষা

zh-min-nan:Tek-gí

map-bms:Basa Jerman

ba:Немец теле

be:Нямецкая мова

be-x-old:Нямецкая мова

bcl:Aleman

bg:Немски език

bar:Deitsche Sproch

bo:འཇར་མན་སྐད།

bs:Njemački jezik

br:Alamaneg

ca:Alemany

cv:Нимĕç чĕлхи

ceb:Inaleman

cs:Němčina

co:Lingua tedesca

cy:Almaeneg

da:Tysk (sprog)

pdc:Modern Hochdeitsch

de:Deutsche Sprache

dv:އަލްމާނީ

nv:Bééshbichʼahii bizaad

dsb:Nimšćina

et:Saksa keel

el:Γερμανική γλώσσα

eml:Tedèsch

es:Idioma alemán

eo:Germana lingvo

ext:Luenga alemana

eu:Aleman

fa:زبان آلمانی

hif:German bhasa

fo:Týskt mál

fr:Allemand

fy:Dútsk

fur:Lenghe todescje

ga:An Ghearmáinis

gv:Germaanish

gd:Gearmailtis

gl:Lingua alemá

gan:德語

gu:જર્મન ભાષા

hak:Tet-ngî

xal:Немшин келн

ko:독일어

hy:Գերմաներեն

hi:जर्मन भाषा

hsb:Němčina

hr:Njemački jezik

io:Germaniana linguo

ilo:Pagsasao nga Aleman

bpy:জার্মান ঠার

id:Bahasa Jerman

ia:Lingua german

ie:German

os:Немыцаг æвзаг

xh:IsiJamani

zu:IsiJalimani

is:Þýska

it:Lingua tedesca

he:גרמנית

jv:Basa Jerman

kl:Tyskisut

kn:ಜರ್ಮನ್ ಭಾಷೆ

krc:Немец тил

ka:გერმანული ენა

csb:Miemiecczi jãzëk

kk:Неміс тілі

kw:Almaynek

rw:Ikidage

sw:Kijerumani

kv:Немеч кыв

kg:Kidoitce

ht:Alman

ku:Zimanê almanî

ky:Немис тили

lad:Lingua alemana

lez:Немец чӀал

ltg:Vuocīšu volūda

la:Lingua Theodisca

lv:Vācu valoda

lb:Däitsch

lt:Vokiečių kalba

lij:Lengua tedesca

li:Duits

ln:Lialémani

jbo:dotybau

lmo:Lengua Tudesca

hu:Német nyelv

mk:Германски јазик

mg:Fiteny alemana

ml:ജർമ്മൻ ഭാഷ

mi:Reo Tiamana

mr:जर्मन भाषा

xmf:გერმანული ნინა

arz:لغه المانى

mzn:آلمانی زبون

ms:Bahasa Jerman

cdo:Dáik-ngṳ̄

mwl:Lhéngua almana

mdf:Германонь кяль

mn:Герман хэл

nah:Teutontlahtōlli

nl:Duits

nds-nl:Duuts

new:जर्मन भाषा

ja:ドイツ語

nap:Lengua germanese

ce:Germanhoyn mott

frr:Tjüsch

pih:Jirman

no:Tysk

nn:Tysk

nrm:Allemaund

nov:Germanum

oc:Alemand

mhr:Немыч йылме

pa:ਜਰਮਨ ਭਾਸ਼ਾ

pfl:Daitschi Sprooch

pnb:جرمن

pap:Alemán

ps:آلماني ژبه

koi:Немеч кыв

km:ភាសាអាល្លឺម៉ង់

pcd:Alemant

pms:Lenga tedësca

tpi:Tok Jeman

nds:Düütsche Spraak

pl:Język niemiecki

pt:Língua alemã

crh:Alman tili

ty:Reo Heremani

ksh:Dütsche Sprooch

ro:Limba germană

rmy:Jermanikani chib

rm:Lingua tudestga

qu:Aliman simi

rue:Нїмецькый язык

ru:Немецкий язык

sah:Ниэмэс тыла

se:Duiskkagiella

sm:Fa'asiamani

sa:जर्मन् भाषा

sc:Limba tedesca

sco:German leid

stq:Düütsk

st:Se-jeremane

sq:Gjuha gjermane

scn:Lingua tidesca

simple:German language

ss:SíJalimáne

sk:Nemčina

sl:Nemščina

cu:Нѣмьчьскъ ѩꙁꙑкъ

szl:Mjymjecko godka

ckb:زمانی ئەڵمانی

sr:Немачки језик

sh:Nemački jezik

fi:Saksan kieli

sv:Tyska

tl:Wikang Aleman

ta:இடாய்ச்சு மொழி

roa-tara:Lènga tedesche

tt:Alman tele

te:జర్మన్ భాష

tet:Lia-alemaun

th:ภาษาเยอรมัน

tg:Забони олмонӣ

chr:ᎠᏂᏙᎢᏥ ᎧᏬᏂᎯᏍᏗ

tr:Almanca

tk:Nemes dili

udm:Немец кыл

uk:Німецька мова

ur:جرمن زبان

ug:نېمىس تىلى

za:Vah Dwzgoz

vec:Łéngua todésca

vep:Germanijan kel'

vi:Tiếng Đức

vo:Deutänapük

fiu-vro:S'aksa kiil

wa:Almand (lingaedje)

zh-classical:德語

vls:Duuts (toale)

war:Inaleman

wuu:德语

yi:דייטשיש

yo:Èdè Jẹ́mánì

zh-yue:德文

diq:Almanki

zea:Duuts

bat-smg:Vuokītiu kalba

zh:德语

![Jablonec nad Nisou (Czech pronunciation: [ˈjablonɛts ˈnad ɲɪsou̯]; German: Gablonz an der Neiße) is a town in northern Bohemia, the second largest town of the Liberec Region. It is known as a mountain resort in the Jizera Mountains, an education centre, and a centre of world-production of glass and jewellery. It has the name from the Lusatian Neisse (called Nisa in the Czech language). Jablonec nad Nisou (Czech pronunciation: [ˈjablonɛts ˈnad ɲɪsou̯]; German: Gablonz an der Neiße) is a town in northern Bohemia, the second largest town of the Liberec Region. It is known as a mountain resort in the Jizera Mountains, an education centre, and a centre of world-production of glass and jewellery. It has the name from the Lusatian Neisse (called Nisa in the Czech language).](http://web.archive.org./web/20120606090449im_/http://cdn3.wn.com/pd/0a/21/c418b7eeb0f8318c7f2c1f6a2534_small.jpg)

![Staufen im Breisgau is a German town in the Breisgau-Hochschwarzwald district of Baden-Württemberg. It has a population of approximately 7700. Additional information may be found (in German) on the Staufen im Breisgau article[1] in the German language Wikipedia. Staufen im Breisgau is a German town in the Breisgau-Hochschwarzwald district of Baden-Württemberg. It has a population of approximately 7700. Additional information may be found (in German) on the Staufen im Breisgau article[1] in the German language Wikipedia.](http://web.archive.org./web/20120606090449im_/http://cdn6.wn.com/pd/1b/00/bcb23501da6b020b740adb6c8726_small.jpg)

![Rijeka (other Croatian dialects: Reka or Rika, Slovene: Reka, Italian and Hungarian Fiume, German: Sankt Veit am Flaum or Pflaum (both historical) ) is the principal seaport of Croatia, located on Kvarner Bay, an inlet of the Adriatic Sea. It has 144,043 (2001) inhabitants[citation needed]. The majority of its citizens, 80.39% (2001 census), are Croats. The Croatian and the Italian version of the city's name mean river in each of the two languages.[1] Rijeka (other Croatian dialects: Reka or Rika, Slovene: Reka, Italian and Hungarian Fiume, German: Sankt Veit am Flaum or Pflaum (both historical) ) is the principal seaport of Croatia, located on Kvarner Bay, an inlet of the Adriatic Sea. It has 144,043 (2001) inhabitants[citation needed]. The majority of its citizens, 80.39% (2001 census), are Croats. The Croatian and the Italian version of the city's name mean river in each of the two languages.[1]](http://web.archive.org./web/20120606090449im_/http://cdn4.wn.com/pd/fb/db/defe4501440f4fe05e03830027ed_small.jpg)