Overview

Brain aneurysm

Brain aneurysm

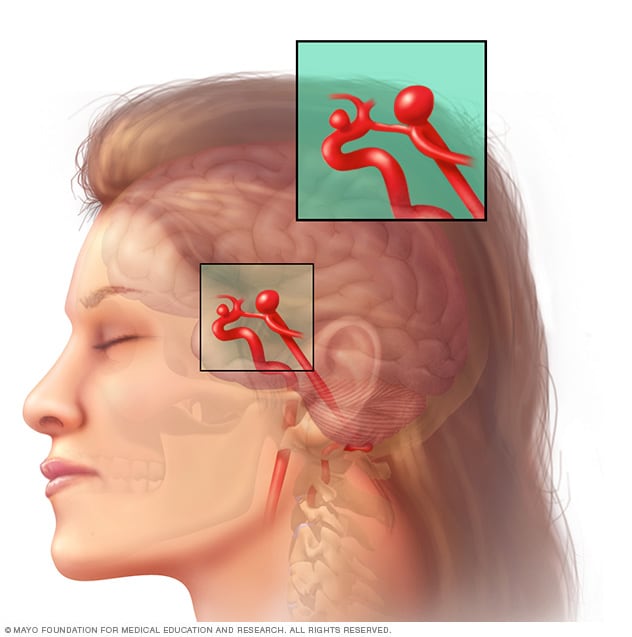

An aneurysm is a ballooning at a weak spot in an artery wall. An aneurysm's walls can be thin enough to rupture. The illustration shows an individual with an unruptured aneurysm. The inset shows what happens when the aneurysm ruptures.

The Dangers of Brain Aneurysm

Aneurysms can lurk without symptoms, but screening can save lives.

Click here for an infographic to learn more

A brain aneurysm (AN-yoo-riz-um) is a bulge or ballooning in a blood vessel in the brain. An aneurysm often looks like a berry hanging on a stem.

A brain aneurysm can leak or rupture, causing bleeding into the brain (hemorrhagic stroke). Most often, a ruptured brain aneurysm occurs in the space between the brain and the thin tissues covering the brain. This type of hemorrhagic stroke is called a subarachnoid hemorrhage.

A ruptured aneurysm quickly becomes life-threatening and requires prompt medical treatment.

Most brain aneurysms, however, don't rupture, create health problems or cause symptoms. Such aneurysms are often detected during tests for other conditions.

Treatment for an unruptured brain aneurysm may be appropriate in some cases and may prevent a rupture in the future. Talk with your health care provider to ensure you understand the best options for your specific needs.

Products & Services

Symptoms

Ruptured aneurysm

A sudden, severe headache is the key symptom of a ruptured aneurysm. This headache is often described as the "worst headache" ever experienced.

In addition to a severe headache, common signs and symptoms of a ruptured aneurysm include:

- Nausea and vomiting

- Stiff neck

- Blurred or double vision

- Sensitivity to light

- Seizure

- A drooping eyelid

- Loss of consciousness

- Confusion

'Leaking' aneurysm

In some cases, an aneurysm may leak a slight amount of blood. This leaking may cause only a sudden, extremely severe headache.

A more severe rupture often follows leaking.

Unruptured aneurysm

An unruptured brain aneurysm may produce no symptoms, particularly if it's small. However, a larger unruptured aneurysm may press on brain tissues and nerves, possibly causing:

- Pain above and behind one eye

- A dilated pupil

- A change in vision or double vision

- Numbness of one side of the face

When to see a doctor

Seek immediate medical attention if you develop a:

- Sudden, extremely severe headache

If you're with someone who complains of a sudden, severe headache or who loses consciousness or has a seizure, call 911 or your local emergency number.

Brain aneurysms develop as a result of thinning artery walls. Aneurysms often form at forks or branches in arteries because those areas of the vessels are weaker.

Although aneurysms can appear anywhere in the brain, they are most common in arteries at the base of the brain.

Mayo Clinic Minute: What is an aneurysm?

An aneurysm is an abnormal bulge or ballooning in the wall of a blood vessel.

"A proportion of these patients will go on to have a rupture. And the challenge with rupture is that it's unpredictable."

Dr. Bernard Bendok says a ruptured aneurysm is a medical emergency that can cause life-threatening bleeding in the brain.

"The typical presentation is somebody who has the worst headache of their life."

Fast treatment is essential. It includes open surgery, or less-invasive options, such as sealing the ruptured artery from within the blood vessel with metal coils and/or stents.

Dr. Bendok says 1 to 2 percent of the population have aneurysms, and only a small percentage of that group will experience a rupture. People who have a family history of aneurysms, have polycystic kidney disease, connective tissue disease, and people who smoke are at increased risk of rupture, and should consider screening. If a rupture happens, fast treatment can save lives.

Causes

The causes of most brain aneurysm are unknown, but a range of factors may increase your risk.

Risk factors

A number of factors can contribute to weakness in an artery wall and increase the risk of a brain aneurysm or aneurysm rupture. Brain aneurysms are more common in adults than in children. They're also more common in women than in men.

Some of these risk factors develop over time, while others are present at birth.

Risk factors that develop over time

These include:

- Older age

- Cigarette smoking

- High blood pressure

- Drug abuse, particularly the use of cocaine

- Heavy alcohol consumption

Some types of aneurysms may occur after a head injury or from certain blood infections.

Risk factors present at birth

Some conditions that are present at birth can be associated with an elevated risk of developing a brain aneurysm. These include:

- Inherited connective tissue disorders, such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, that weaken blood vessels

- Polycystic kidney disease, an inherited disorder that results in fluid-filled sacs in the kidneys and usually increases blood pressure

- Narrow aorta (coarctation of the aorta), the large blood vessel that delivers oxygen-rich blood from the heart to the body

- Brain arteriovenous malformation (AVM), in which the arteries and veins in the brain are tangled, interrupting blood flow

- Family history of brain aneurysm, particularly a first-degree relative, such as a parent, brother, sister or child

Complications

When a brain aneurysm ruptures, the bleeding usually lasts only a few seconds. However, the blood can cause direct damage to surrounding cells, and the bleeding can damage or kill other cells. It also increases pressure inside the skull.

If the pressure becomes too high, it may disrupt the blood and oxygen supply to the brain and loss of consciousness or even death may occur.

Complications that can develop after the rupture of an aneurysm include:

- Re-bleeding. An aneurysm that has ruptured or leaked is at risk of bleeding again. Re-bleeding can cause further damage to brain cells.

- Narrowed blood vessels in the brain. After a brain aneurysm ruptures, blood vessels in the brain may contract and narrow (vasospasm). This condition can cause an ischemic stroke, in which there's limited blood flow to brain cells, causing additional cell damage and loss.

- A buildup of fluid within the brain (hydrocephalus). Most often, a ruptured brain aneurysm occurs in the space between the brain and the thin tissues covering the brain. The blood can block the movement of fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord. As a result, an excess of fluid puts pressure on the brain and can damage tissues.

- Change in sodium level. Bleeding in the brain can disrupt the balance of sodium in the blood. This may occur from damage to the hypothalamus, an area near the base of the brain. A drop in blood sodium levels can lead to swelling of brain cells and permanent damage.