Accuracy of Depression Screening Tools for Identifying Postpartum Depression Among Urban Mothers

Abstract

Objective

The goal was to describe the accuracy of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II), and Postpartum Depression Screening Scale (PDSS) in identifying major depressive disorder (MDD) or minor depressive disorder (MnDD) in low-income, urban mothers attending well childcare (WCC) visits during the postpartum year.

Design/Methods

Mothers (N=198) attending WCC visits with their infants 0 to 14 months of age completed a psychiatric diagnostic interview (standard method) and 3 screening tools. The sensitivity and specificity of each screening tool were calculated in comparison with diagnoses of MDD or MDD/MnDD. Receiver operating characteristic curves were calculated and the areas under the curves for each tool were compared to assess accuracy for the entire sample (representing the postpartum year) and sub-samples (representing early, middle and late postpartum time frames). Optimal cut-points were calculated.

Results

At some point between 2 weeks and 14 months postpartum, 56% of mothers met criteria for either MDD (37%) or MnDD (19%). When used as a continuous measures, all scales performed equally well (areas under the curves of ≥ 0.8). With traditional cut-points, the measures did not perform at the expected levels of sensitivity and specificity. Optimal cut-points for the BDI-II (≥14 for MDD, ≥11 for MDD/MnDD) and EPDS (≥9 for MDD, ≥7 for MDD/MnDD) were lower than currently recommended. For the PDSS, the optimal cut-point was consistent with current guidelines for MDD (≥80) but higher than recommended for MDD/MnDD (≥ 77).

Conclusions

Large proportions of low-income, urban mothers attending WCC visits experience MDD or MnDD during the postpartum year. The EPDS, BDI-II and PDSS have high accuracy in identifying depression but cutoff points may need to be altered to more accurately identify depression in urban, low-income mothers.

Introduction

Postpartum depression affects an average of 1 out of every 7 new mothers in the United States1 with rates as high as 1 out of 4 among poor and minority women.2–4 Multiple, long term negative effects for mothers and infants are well described.5, 5–8 Recent efforts have focused on improving identification of women with postpartum depression.9–11 To increase the potential for early intervention, primary care providers, including pediatricians, are encouraged to screen mothers.10–14 However, practitioners are unsure which instruments to use and whether one is preferable.

Pediatric practitioners must have confidence that the tools accurately identify depression among the women in their diverse practices. Several studies have assessed the accuracy of screening tools in identifying postpartum depression but they have several limitations1. Most did not include significant numbers of low-income or minority women who have higher rates of postpartum depression. Also, most assessed the tools’ accuracy in the early postpartum period (2 and 12 weeks). Since depression can occur anytime in the postpartum year15, 16, and some providers screen mothers throughout the year11, evaluation of the tools’ accuracy at different points throughout the year is critical. Finally, despite endorsement of depression screening in primary care settings17 and established feasibility of postpartum depression screening in pediatric clinics 10, 11, 18–20 few accuracy studies have been conducted in primary care settings, including pediatrics, 21, 22

To address these limitations, we conducted a cross-sectional study among a cohort of low-income mothers attending WCC visits at a pediatric clinic. The study was designed to establish the sensitivity, specificity and operating characteristics of three depression screening tools for low-income urban women during the postpartum year.

Method

The study was approved by the University of Rochester Research Subjects Review Board. All participants provided written informed consent.

Recruitment and Sample

Between April 1, 2003 and August 31, 2005, a convenience sample of mothers (N=647) of infants ≤14 months, ≥ 18 years, and attending a WCC visit during the postpartum year at the Strong Pediatric Practice at Golisano Children’s Hospital were invited to complete a demographic questionnaire and Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)23, 24 and return for a diagnostic interview. Eight were ineligible due to maternal age (<18), language barriers, or previous participation in the study (completion of the SCID earlier or with a previous infant). Of 639 eligible women, 217 (34%) refused but provided non-identifiable demographic information and 422 (66%) provided written informed consent, completed the demographic questionnaire and CES-D. (Figure 1) Of the 422, 28 refused further participation, 9 were excluded, and 198 completed the psychiatric diagnostic interview (Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV or SCID25).(Figure 1)

Retention of Subjects

Forty-nine percent (N=187) of eligible women who agreed to complete the SCID did not return. Difficulties with retention, similar to those described by other investigators26, were recognized and addressed early.27 To improve follow-up we, 1) offered an immediate SCID; 2), provided an appointment card at the time of consent 3) sent a confirmation letter, and 4) placed a confirmation phone call 12–48 hours before the appointment. If a subject did not return, we attempted to call and reschedule at her convenience. Subjects received between 1 and 9 calls (mean 4.1, SD 2.06) and were rescheduled a maximum of 3 times. We also followed-up in person at the next WCC visit. Subjects received $40 for participation in the SCID.

Descriptive Group Assignments

Because of the cross-sectional study design, infant age at the time of the maternal interview was used to assign subjects to a postpartum group to assess the screening tools’ accuracy at different points in the postpartum year: 2 weeks to 4 months (Early), >4 to 8 months (Middle), and >8 to 14 months (Late). The groups were chosen to assess the utility of the tools throughout the year, and because the group timeframes coincide with at least 2 WCC visits.

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) at initial recruitment: The CES-D is a 20-item self-report measure that has been used to screen for postpartum depression.23, 24, 28 It was used for two primary purposes. To assess for potential bias due to depression, an initial depression measure that was not the focus of the accuracy study, was needed to compare the women who did and did not complete the SCID. In addition, to determine the ROC curves, the sample size is based on the assumption of roughly equal numbers of depressed and non-depressed subjects. By conducting the CES-D, the distribution of women with high (≥16) and low CES-D (<16) scores was monitored. Interviewers were blind to all screening tools’ scores (including the CES-D).

To determine minimum group size for comparing ROC curves across the postpartum groups, power analysis using Power Analysis and Sample Size software (Hintze, J. PASS. NCSS. LLC, Kaysville, Utah). 2008, with 50% depressed subjects, indicated that a sample size of 60 was sufficient to have enough power (80%) to detect a difference of 0.13 to 0.16 depending on the true AUCs.

Measures

Demographic information included maternal race, ethnicity, age, marital status, number of children, insurance status and education.

Screening Tools

The tools were placed in random order in sealed envelopes to ensure they were not answered in a biased fashion.

- The Beck Depression Inventory – Second Edition II (BDI-II), a 21-item self-report questionnaire that assesses cognitive, behavioral, affective and somatic symptoms of depression, was developed to correspond to the criteria for DSM-IV depressive diagnoses. 29–32 It has a high validity with depression severity ratings. Suggested cut-points are: 0–13 minimal, 14–19 mild; 20–28 moderate, and 29–63 more severe depression.32 As required, the BDI-II individual forms were purchased specifically for use in this study.

- The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), a 10-item self-administered questionnaire developed to assess depression in postpartum women has been validated against the Research Diagnostic Criteria for MDD or MnDD.33 The EPDS has been validated in a variety settings and community samples, with the majority of studies focusing on the 6–8 week postpartum period.33–36 Scores range from 0–30 with a cut-point ≥ 10 recommended to detect MDD/MnDD with sensitivities greater than 90% and specificities between 77% and 88%.33, 37, 38 A cut-point ≥ 13 is recommended to detect MDD with a sensitivity of 85–100% and specificity of 80–95%. 33, 37, 38 The EPDS form indicated the original reference and acknowledged the original authors as required for its use free of charge.

- The Postpartum Depression Screening Scale (PDSS) is a 35-item self-report questionnaire that assesses seven dimensions (sleeping/eating disturbances, anxiety/insecurity, emotional liability, cognitive impairment, loss of self, guilt/shame, and contemplating harming oneself) in postpartum women.39, 40 The PDSS has a range of scores from 35 to 175. Scores are interpreted as follows: 35–59 normal adjustment, 60–79 significant symptoms of postpartum depression, 80–75 positive screen for MDD.41 The PDSS has been validated against the SCID-IV in a sample of primarily White, married women with higher levels of education.41 With a score ≥ 80, it had a sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 98% for MDD. With a score ≥60, the sensitivity was 91% and specificity 72% for MDD/MnDD. As required, the PDSS individual forms were purchased specifically for use in this study.

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) is a semi-structured interview developed to assess 33 DSM Axis I diagnoses in adults.25, 42 It is considered the “gold standard” to characterize study samples in terms of current psychiatric diagnoses. In this study it was used to establish DSM IV Axis I diagnoses including MDD and MnDD, dysthymia, bipolar, substance use, anxiety, and psychotic disorders. It was administered by a trained rater and reviewed by a psychiatrist (LHC), two psychologists (NLT, SG) and trained raters (HW, EW) to confirm the diagnostic decision. Consensus team members were blind to the screening tool scores.

Analyses

To compare characteristics of mothers who did and did not complete the SCID, we used T-tests and Wilcoxon Rank-Sum (Mann-Whitney) Tests for continuous demographic variables and Chi-square tests for categorical variables.

To assess the accuracy of the EPDS, BDI, and PDSS, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were computed, for the whole sample as well as for each postpartum group for each tool. In each possible threshold based on the sample, we computed the estimates of the corresponding sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive value (PPV). The ROC curve plots the sensitivity of a measure on the Y-axis and (1-sensitivity) on the X-axis and measures the overall accuracy of a test. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) is the most important summary index of the ROC curve. An ROC curve with AUC > 0.5 suggests the test is informative in that it is better than classifying subjects randomly. An ROC curve with AUC > 0.8 is generally considered as an accurate test. The closer the curve to the upper-left corner (point [0,1]), the bigger the AUC, and the more accurate the test.43

For each of the empirical ROC curve estimates (based on the empirical estimates of the sensitivities and specificities at the observed test levels), the empirical AUC and the associated standard error were estimated. Because each subject completed each tool, their results are correlated. Methods developed by Delong and colleagues 44, which address such within-subject correlations, were used to compare the accuracies among the screening tools, both over the entire sample and for each postpartum group.

The AUCs of each tool were compared across the postpartum groups to assess differential accuracy across the groups. Optimal cut-points for the screening tools were recommended based on the empirical ROC curves. Since sensitivity and specificity estimates change in the opposite direction when the cut-point varies, a good choice should balance between sensitivity and specificity, while maintaining the ROC curve as close to the upper-left corner as possible. We present the results of the optimal cut-points as computed using the criteria that minimizes the Euclidean distance from (sensitivity, specificity) to the point (1,1) in the X-Y plane.45

Results

Sample Description

There were no statistically significant differences in number of children (p = 0.34) or level of education (0.27) between the women who did (N=422) and did not agree (N=217) to participate. There were statistically significant differences in age (p = 0.005), race (p = 0.004), marital status (p = 0.004) and insurance types (p = 0.009) between these groups. Older women, Hispanic women, married women, and women who had private insurance were more likely to refuse.

Of the 422 women who consented to participate, 385 (91%) agreed to complete the SCID but 49% (N=187) did not return. (Figure 1) There were no statistically significant differences between women who did (N=198) and did not (N=224) complete the SCID with regard to maternal age, education, or number of children, mean CES-D scores or proportion of high CES-D scores, but Hispanic women, married women and women with private insurance were less likely to complete the SCID. (Table 1)

Table 1

Demographic characteristics of subjects who completed and who did not complete the SCID

| Variable | Completed SCID (N=198) | Did Not Complete SCID (N=224) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Mean (SD) | 24.6 (5.6) | 24.3 (5.0) | 0.46 |

| Range | 18–45 | 18–44 | |

| Race: | |||

| African American | 137 (69.9%) | 141 (64.4%) | 0.02 |

| Caucasian | 34 (17.4%) | 34 (15.5%) | |

| Hispanic-Latino | 14 (7.1%) | 26 (11.9%) | |

| Mixed | 11 (5.6%) | 18 (8.2%) | |

| Marital Status | |||

| Never Married | 135 (68.9%) | 152 (67.9%) | 0.001 |

| Married | 22 (11.2%) | 43 (19.2%) | |

| Living with partner | 28 (14.3%) | 23 (10.3%) | |

| Separated/divorced | 11 (5.6%) | 6 (2.7%) | |

| Education | |||

| < high school grad | 90 (45.5%) | 88 (39.6%) | 0.29 |

| High school grad or GED | 68 (34.3%) | 93 (41.9%) | |

| >HS education | 40 (20.2%) | 41 (18.5%) | |

| Number of children: | |||

| 1 | 84 (42.4%) | 84 (37.5%) | 0.74 |

| 2 | 47 (23.7%) | 56 (25.0%) | |

| 3 | 25 (12.6%) | 47 (21.0%) | |

| 4 | 24 (12.1%) | 23 (10.3%) | |

| 5 or more | 18 ( 9.1%) | 14 ( 6.3%) | |

| Insurance | |||

| Public* | 164 (82.8%) | 122 (54.7%) | <0.0001 |

| Private | 24 (12.1%) | 88 (39.5%) | |

| Uninsured or Other | 10 ( 5.1%) | 13 (5.8%) | |

| CESD mean (SD) | 17.54 (11.77) | 17.64 (11.25) | 0.79 |

| CESD ≥ 16 | 94 (47.5%) | 116 (51.8%) | 0.38 |

Approximately equal numbers of women were recruited into each postpartum group. (Table 2) There were no statistically significant differences in the percentage with MDD or MDD/MnDD among the groups. All groups had rates exceeding 50% for MDD or MnDD.

Table 2

Proportion of mothers with SCID depression diagnoses for whole sample and by postpartum group

| Group (Infant Age) | N | Major Depression | Minor Depression | Major or Minor Depression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALL GROUPS | 198 | 73 (37%) | 38 (19%) | 111 (56%) |

| Early Postpartum Group 2 weeks – 4.0 months | 68 | 22 (32%) | 14 (21%) | 36 (53%) |

| Middle Postpartum Group 4.1–8.0 months | 67 | 26 (39%) | 16 (24%) | 42 (63%) |

| Late Postpartum Group 8.1–14 months | 63 | 25 (40%) | 8 (13%) | 33 (53%) |

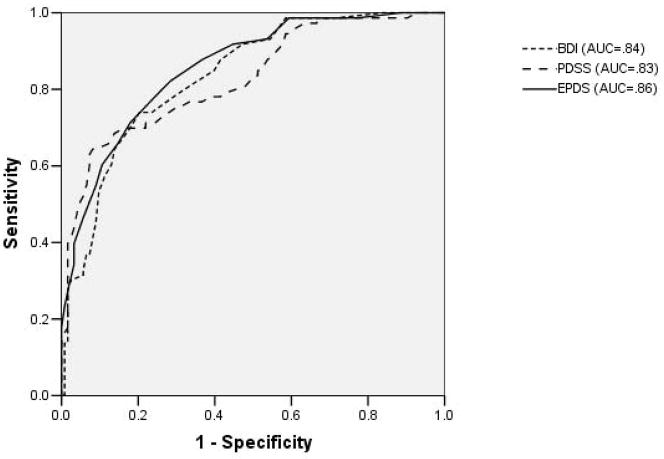

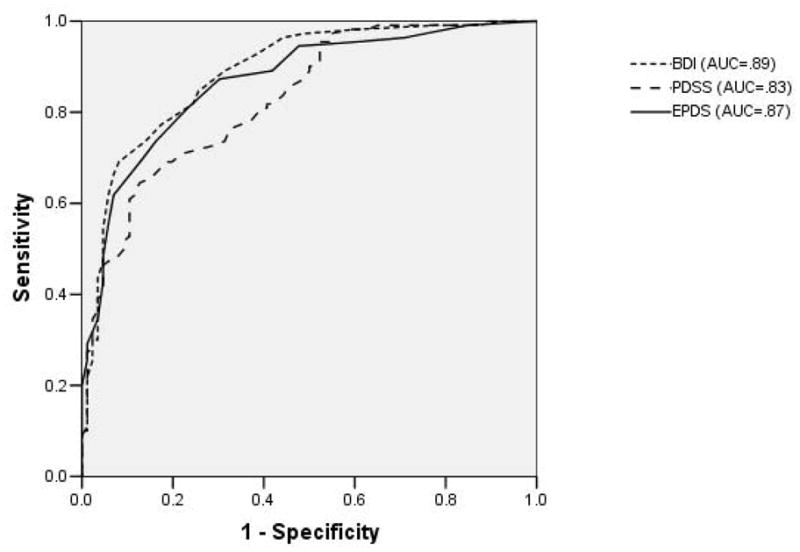

Receiver Operating Characteristic Curves of Screening Tools

Postpartum year (Infants’ ages 2–60 weeks)

When evaluated for the entire sample (N=198), each tool performed well for MDD and MDD/MnDD with AUCs of 0.8 or higher. (Figures 2 and and3)3) The AUCs for the BDI, EPDS and PDSS were 0.84 (0.78–0.89), 0.86 (0.81–0.91), 0.83 (0.79–0.89) for MDD respectively and for MDD/MnDD, they were 0.89 (0.84–0.93), 0.87 (0.82–0.92), 0.83 (0.78–0.89) respectively. There were no statistically significant differences in the AUC (MDD Chi square = 1.96, P = 0.38, MDD/MnDD Chi square = 5.64, p = 0.06) between the tools although there is a trend toward significance for MDD/MnDD.

Comparison of receiver operating characteristic curves for each depression tool for the whole sample (N=198)

REPLACE WITH ROC CURVES OF MDD and MDD/MnDD

Postpartum Groups

The AUC of the tools were compared to each other within each postpartum group. No statistically significant differences were found between the tools for either MDD or MDD/MnDD within any postpartum group. (Table 3)

Table 3

Accuracy of each depression screening tool for each postpartum group and comparison of receiver operating characteristic curves of screening tools for each postpartum group

| Major Depression | Major or Minor Depression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC (Lower-Upper Bound) | Group Chi Square, p value | AUC (Lower-Upper Bound) | Group Chi Square, p value | ||

| Early Group (N=68) | BDI –II EPDS PDSS | 0.90 (0.82–0.97) 0.87 (0.79–0.95) 0.83 (0.72–0.94) | 1.62 p=0.44 | 0.92 (0.85–1.0) 0.88 (0.80–0.97) 0.83 (0.74–0.93) | 3.87 P= 0.14 |

| Middle Group (N=67) | BDI –II EPDS PDSS | 0.84 (0.75–0.93) 0.91 (0.84–0.97) 0.89 (0.80–0.97) | 3.69 p=0.16 | 0.88 (0.80–0.96) 0.86 (0.77–0.95) 0.86 (0.78–0.95) | 0.48 p=0.79 |

| Late Group (N=63) | BDI –II EPDS PDSS | 0.78 (0.66–0.89) 0.79 (0.67–0.90) 0.77 (0.64–0.89) | 0.22 p=0.90 | 0.84 (0.74–0.94) 0.86 (0.76–0.95) 0.79 (0.67–0.90) | 2.23 p=0.33 |

To assess potential differences in a tool’s accuracy related to a postpartum period, the AUCs were calculated for each tool for each postpartum group (Table 3) and compared across the groups. When the AUC of each tool was compared across groups, no statistically significant differences were found. In the Late Group, for MDD, no tool reached an AUC of 0.8.

Sensitivity and Specificity of Screening Tools

Postpartum year (infant ages 2 – 60 weeks)

We assessed the sensitivity and specificity to estimate the optimal cut-point for each screening instrument, and compared this to published cut-points. For the BDI-II and EPDS, the optimal cut-points for MDD or MDD/MnDD were lower than published guidelines. 32, 33, 46 (Table 4) For the PDSS, the optimal cut-point for MDD/MnDD is within the range published as consistent with significant symptoms (≥77) however, it is 17 points greater than recommended for Depressive Disorder NOS (or MnDD) (≥60).41 The cut-point for MDD (≥80) is consistent with published recommendations.41

Table 4

Sensitivity, Specificity and Optimal Cut-Points

| Standard | Optimal Overall | Optimal Early | Optimal Middle | Optimal Late | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cut- Point | Sensitivity, Specificity | Cut- Point | Sensitivity, Specificity | Cut- Point | Sensitivity, Specificity | Cut- Point | Sensitivity, Specificity | Cut- Point | Sensitivity, Specificity | |

| BDI-II* | ||||||||||

| MDD | ≥20 | 45.3, 91.1 | ≥ 14 | 74.0, 79.7 | ≥ 14 | 81.8, 84.4 | ≥ 17 | 73.1, 80.5 | ≥ 16 | 60.0, 89.2 |

| MDD/MnDD | ≥14 | 66.4, 93.0 | ≥ 11 | 77.3, 82.6 | ≥ 10 | 91.7, 87.1 | ≥ 13 | 69.0, 96.0 | ≥ 11 | 71.9, 83.3 |

| EPDS | ||||||||||

| MDD | ≥13 | 54.8, 91.2 | ≥ 9 | 78.1, 76.0 | ≥ 8 | 86.4,76.1 | ≥ 10 | 73.1, 84.6 | ≥ 8 | 72.0, 73.7 |

| MDD/MnDD | ≥ 10 | 61.3, 93.1 | ≥ 7 | 81.1, 77.0 | ≥ 7 | 77.7, 87.5 | ≥ 6 | 88.1, 68.0 | ≥ 8 | 72.7, 86.7 |

| PDSS** | ||||||||||

| MDD | ≥ 80 | 71.2, 77.6 | ≥ 80 | 71.2, 77.6 | ≥ 80 | 68.2, 78.3 | ≥ 80 | 79.5, 78.0 | ≥ 73 | 72.0, 68.4 |

| MDD/MnDD | ≥ 60 | 89.2, 49.4 | ≥ 77 | 69.4, 81.6 | ≥ 77 | 66.7, 84.4 | ≥ 75 | 78.6, 80.0 | ≥ 73 | 69.7, 76.7 |

Moderate 20–28

Severe 29–63

Significant Depressive Symptoms 60–79

Major Depression 80–175

Postpartum Groups

Optimal cut-points for each postpartum group ranged from 0–3 points from the optimal cut-points for the whole sample. (Table 4)

Discussion

Our study is the first to describe the prevalence of MDD and MnDD using a diagnostic interview among a population of mostly low-income, black young mothers attending WCC visits in an urban pediatric clinic. It is also the first to describe the accuracy of depression screening tools among this understudied population of mothers.

Prevalence

The finding that more than half (56%) of these new mothers meet criteria for MDD or MnDD was unexpected. Many studies cite high rates of depressive symptoms with screening tools2, 3, 11, but none has quantified the prevalence of depression by diagnostic interview in this disadvantaged population. The unexpectedly high rate may due to selection bias. The study participants may have self-identified as needing assistance with their depression and therefore were more likely to meet diagnostic criteria for MDD/MnDD than non-participants. A second possibility is that, based on the differences in sociodemographics between participants and non-participants, the final sample may have been the most economically and socially disadvantaged and therefore at greatest risk for depression. Because of the potential sample biases we cannot generalize the high prevalence to the larger clinic population but we can underscore the need for a group of mothers with high levels of depression to be identified and referred for care.

Another finding is that the proportion of depressed women was essentially equivalent during any 4 month infant age range in the postpartum year. Because of the cross-sectional study design, we cannot accurately identify when incident or recurrent cases occurred. However, the finding, which is similar to previous findings 15, supports the practice of screening at early and late first year WCC visits.

Accuracy of Tools

Our findings suggest that the BDI-II, EPDS and PDSS are equally accurate in identifying depression in low-income, black mothers during the postpartum year. The performance of the tools did show some minor variability at different postpartum time points but did not reach a level of statistical significance. Therefore, the findings suggest that pediatric practitioners can be confident using these tools at any first year WCC visit. These findings are similar to those of a study conducted in Pittsburgh with the PDSS-Short Form (PDSS-SF), Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and EPDS in which the AUCs for the continuous scales did not show any significant differences. 21

Cut-Points

While providers may be reassured that these tools are accurate at detecting depression, presumably, they use published cut-points to guide their clinical evaluations and referrals. Our findings suggest that in this population, using the established cut-points for the BDI-II and EPDS, may lead a clinician to fail to identify many women with depression. Other studies found similar suboptimal performance by screening tools at traditional cut-points.21 While replication of our findings in other settings with similar populations is required to make final recommendations for changing cut-points, pediatric practitioners who use the EPDS or BDI-II should be aware that using traditional cut-points may not be as accurate as previously thought and they may consider decreasing the cut-points for optimal performance. (Table 4) Scores within 2–3 points below traditional cut-points may indicate a need for further evaluation. Studies from different countries and conducted with different ethnic populations have indicated a range of optimal cut-points.34–36, 47–49 If providers use the PDSS our findings support the recommended cut-point (80) for detection of MDD. However, the PDSS appears to overestimate the number of women with MDD/MnDD with a cut-point of 60 thereby potentially unnecessarily labeling women as depressed. Using a higher cut-point may decrease unnecessary referrals. As with any screening tool, clinical evaluation of the specific situation is necessary.

Reasons for the lower optimal cut-points for the BDI-II and the EPDS are not clear. This high risk population may have higher rates of co-morbid medical or mental health concerns that may influence the optimal cut-points. Anxiety, alone, cannot be the explanation as the EPDS has an anxiety subscale as does the PDSS but the optimal cut-points are in opposite directions. Because the BDI-II relies more heavily on somatic symptoms, it might be expected to over-estimate the number of depressed women. Our findings are the reverse. Further exploration of the underlying mechanisms for the different optimal cut-points is indicated.

Practice Implications

With the finding that all three tools perform equally well in a low-income black population of new mothers, providers must consider the advantages and disadvantages of each tool. The EPDS is a short screening tool, easy to complete, free to providers, has been used in multiple ethnic and socioeconomic groups and settings and is available in multiple languages. The PDSS allows clinicians to target interventions or referrals as it identifies multiple domains and it is available in Spanish. The disadvantages of the PDSS are its length and cost per use. Advantages of the BDI-II are that many providers are comfortable with its use, it is available in Spanish, and it has been used with adolescents and minority populations. The disadvantages are that it focuses on somatic symptoms that may overlap with normal postpartum adaptation, must be purchased and is not traditionally used with a dichotomous cut-point structure. Providers will need to take all this information into consideration when choosing the right screening tool for their clinic and population.

Strengths/Limitations

The sample - urban, low-income, black mothers - is a primary strength of this study as it represents a large number of women in the US about whom little is known. Second, the population was recruited from a pediatric clinic which is important when considering the prevalence of depression among mothers presenting to WCC visits. Third, the sampling size and strategy allowed for sufficient sample sizes to test the accuracy of the tools in the postpartum year and within time periods corresponding to WCC visits, as demonstrated by the relatively tight 95% confidence intervals around the estimated AUCs of the three instruments. The sufficient numbers of depressed and non-depressed women, and the use of a diagnostic interview, allowed us to address prior studies’ limitations.

This study also had limitations. By purposefully sampling from one urban academic medical center clinic that serves a low-income, high risk population, the findings cannot be generalized to more ethnically or socioeconomically diverse populations or other types of pediatric primary care settings. Replication in other sites and types of clinics as well as among ethnically diverse populations is warranted. Another limitation is the cross-sectional study design. Validation of the tools with a longitudinal prospective study would help to determine the tools’ accuracy at repeated visits. Finally, the large proportion of women lost to follow-up limited our ability to determine diagnoses or test the screening tools in women who may represent a slightly different population based on the differences in demographic characteristics. Future studies should attempt to obtain broader representation of this portion of the population.

Conclusions

Depression is highly prevalent among low-income, black mothers attending WCC visits during the postpartum year and can be accurately identified by screening them with the EPDS, PDSS or BDI-II. Depending on the clinical population and screening tool, pediatric practitioners may need to alter the cut-point to more effectively identify those who could benefit from referral and treatment.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health, Award Number K23 MH64476 (Chaudron). Dr Wisner’s work on this study was supported in part by National Institute of Mental Health R01 MH071825 and 2 R01 MH 057102.

We would like to thank the women who participated in this study. We would like to acknowledge the members of our consensus group, Stephanie Gamble, PhD (SG), Nancy Talbot, PhD (NT), Holly Wadkins (HW), Erin Ward (EW).

Abbreviations

- WCC

- Well Childcare

- MDD

- Major Depressive Disorder

- MnDD

- Minor Depressive Disorder

- EPDS

- Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale

- BDI-II

- Beck Depression Inventory – Second Edition II

- PDSS

- Postpartum Depression Screening Scale

- PDSS-SF

- Postpartum Depression Screening Scale – Short Form

- SCID

- Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV

- CES-D

- Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression Scale

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure:

Dr. Katherine Wisner is on the Advisory Board for Eli Lilly Corp and received a donation of active and placebo transdermal estradiol patches for an NIMH funded study from Novartis (novogyne).

Linda Chaudron, MD, MS; Peter Szilagyi, MD, MPH; Wan Tang, PhD; Elizabeth Anson, MS; Nancy Talbot, PhD; Holly Wadkins, MS: Xin Tu, PhD, have no disclosures.