What is a c-section?

A c-section, or cesarean section, is surgical delivery of a baby through incisions in the mother's abdomen and uterus. In some circumstances, a c-section is scheduled in advance. In others, the surgery is needed due to an unforeseen issue. If you or your baby is in imminent danger, you'll have an emergency c-section.

C-sections are very common. About 32 percent of births in America are through cesarean delivery.

C-section rates began rising significantly in the mid-1990s. Doctors are trying to reduce the use of unnecessary c-sections, but sometimes a cesarean is needed to protect the health of the mother or her baby.

How long does a c-section take?

Expect your c-section to take 45 minutes to an hour and a half. Extracting your baby is usually very fast, between 1 to 15 minutes. Suturing your uterus and abdomen closed takes longer.

Typically, your partner can be with you during a c-section. He or she will be asked to wear operating room garb and take a seat by your head.

C-section procedure: What happens during a c section?

Wondering what happens during cesarean deliveries? Here's the procedure step by step.

What happens right before a c-section:

- Consent: First, your healthcare provider will explain why a c-section is necessary, and you'll be asked to sign a consent form. The risks, benefits, and alternatives to a cesarean will be explained and you should be able to ask all of your questions and get them answered. (If it's an emergency, this process will be done very quickly.) If your care provider is a midwife, you'll be assigned an obstetrician for the surgery.

- Anesthesia: An anesthesiologist will review various pain-management options. It's rare these days to be given general anesthesia for a c-section. More likely, you'll be given an epidural or spinal block, which will numb the lower half of your body but leave you awake and alert for the birth of your baby. If you've already had an epidural for pain relief during labor, it will likely be used for your c-section as well. Before the surgery, you'll get extra medication to ensure that you're completely numb. You'll feel some pressure and tugging during a cesarean delivery, but no pain.

- Catheter and IV setup: A catheter is inserted into your urethra to drain urine from your bladder during the procedure. Typically, nurses will do this after your spinal or epidural is placed so you won't feel it. An IV is started (for fluids and medications) if you don't have one already. You'll be given antibiotics through your IV to help prevent infection after the operation.

- Hair removal: A nurse may trim the top section of your pubic hair with electric clippers. (Don't shave the area yourself within 48 hours of your c-section – this can increase skin infections.)

- Antacids: You may be given an antacid medication to drink before your c-section as a precautionary measure. The antacid neutralizes your stomach acid so it won't damage your lung tissue if you vomit during the surgery and accidently inhale that material.

What happens during a c-section:

- Incision prep: Once the anesthesia has taken effect, your belly will be cleaned with an antiseptic. To start the surgery, your doctor will make a small, horizontal incision in the skin above your pubic bone (sometimes called a "bikini cut").

- Reaching the uterus: Your doctor will cut through the underlying tissue, working her way down to your uterus. When she reaches your abdominal muscles, she'll separate them in the middle and spread them apart to expose the uterus underneath.

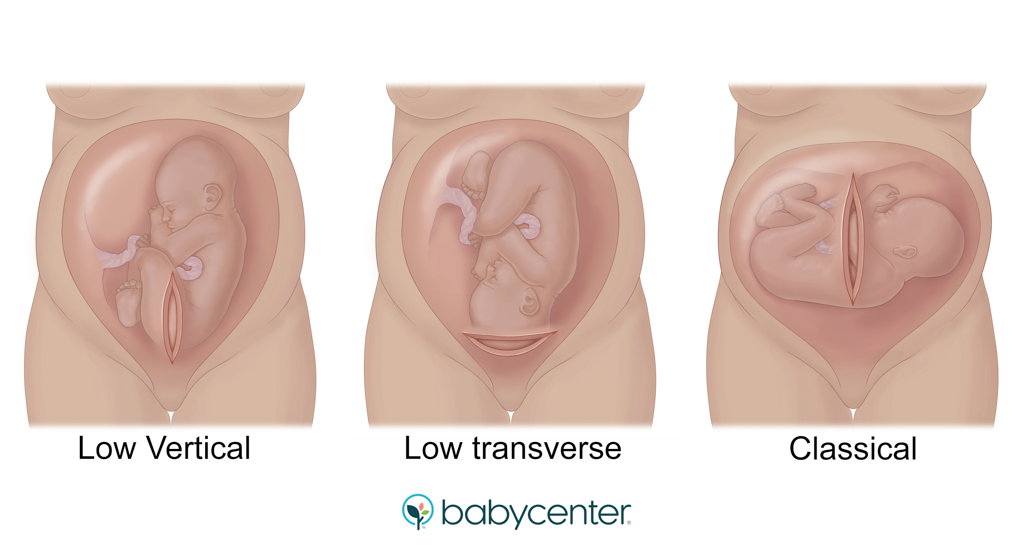

- Opening the uterus: When the doctor reaches your uterus, she'll probably make a horizontal cut in the lower section. This is called a low-transverse uterine incision. (In rare circumstances, the doctor may need to use a vertical or "classical" uterine incision. If you have a vertical incision, it's recommended that you have cesarean deliveries with any future pregnancies.)

- Delivering the baby: Your doctor will deliver your baby by lifting your baby's head out (or the feet or behind if your baby is breech) and pushing on your abdomen. You'll briefly feel a lot of pressure. Once the umbilical cord is cut, you'll have a chance to see your baby briefly before he's handed off to a pediatrician or nurse (usually in the same room). While they examine your newborn, your doctor will deliver your placenta and then begin the process of finishing the surgery.

- Meeting your baby: After your baby has been examined, the pediatrician or nurse may hand him to your partner, who can hold him right next to you so you can admire, nuzzle, and kiss him while your surgery is finished. You may be able to have skin-to-skin contact in the operating room if you're feeling up to it.

- Repairing each layer: Your doctor will use stitches that dissolve to close the incision in your uterus and other internal layers. For closing the final layer – the skin – your doctor may use stitches that dissolve, skin glue, or staples, which are usually removed three days to a week later.

What happens during recovery from a c-section:

- Recovery time: After the surgery is complete, you'll be brought to the recovery room, where you'll be closely monitored for a few hours. Many women feel just fine after surgery, but experiences vary. You may feel tired, nauseated, or itchy from the epidural. Your caregiver can give you medication to minimize any discomfort. You'll receive fluids through your IV until you can eat and drink.

- Holding your baby: If your baby is fine, she'll be with you in the recovery room and you can hold her skin to skin.

- Breastfeeding your baby: If you plan to breastfeed, try now. Positioning can be awkward at first, so ask your nurse for help. (The football hold may work best.)

- Pain relief: You'll be given pain medication through your IV, followed by pills as necessary when you're able to eat and drink. Most hospitals encourage women to take regularly scheduled ibuprofen to decrease their need for stronger medications like narcotics. Many hospitals provide other non-narcotic pain relief methods like lidocaine patches, too.

Reasons for a scheduled c-section

In some cases, a c-section is safer for you and your baby than a vaginal delivery. For example, your provider may recommend a planned c-section if:

- You had a previous c-section with a vertical uterine incision. This "classical" incision is relatively rare, but it heightens the risk of your uterus rupturing during a subsequent vaginal delivery. Your doctor will need to look at your medical records to confirm the type of incision you've had because the scar on your belly doesn't always match the one on your uterus.

- You've had more than one cesarean delivery. Multiple past c-sections increase your risk of uterine rupture when giving birth vaginally. Your doctor will consider other factors such as your age and whether you've had a prior vaginal birth when discussing your options. Note: If you've had only one previous c-section, with a horizontal uterine incision, you may be a good candidate for a vaginal birth after cesarean, or VBAC.

- You've had some other kind of uterine surgery. A common example is a myomectomy (the surgical removal of fibroids), which increases the risk that your uterus will rupture during a vaginal delivery.

- You're carrying more than one baby. You might be able to deliver twins vaginally, or you may need a cesarean, depending on factors like how far along in the pregnancy you are when delivering and the positions of the twins. The more babies you're carrying, the more likely it is you'll need a c-section.

- Your baby is expected to be very large. This is a condition known as macrosomia.

- Your baby is in a breech or transverse position.

- You're near full-term and have placenta previa. This is a condition where the placenta is so low in the uterus that it covers the cervix.

- You have an obstruction. An example is a large fibroid that would make a vaginal delivery difficult or impossible.

- The baby has an abnormality. Certain malformations can make a vaginal birth risky, such as some neural tube defects.

- You're HIV-positive. If blood tests done near the end of pregnancy show that you have a high viral load, you'll likely need a c-section.

Unless there's a medical need to deliver your baby sooner, your caregiver will schedule your surgery for no earlier than 39 weeks.

Reasons for an emergency c-section

You may need to have an unplanned or emergency c-section if problems arise that make continuing labor dangerous to you or your baby, such as:

- Heart rate problems. If your baby's heart rate indicates that he isn't getting enough oxygen, your doctor may decide that continued labor or induction isn't safe for your baby.

- The umbilical cord slips through your cervix. This is called a prolapsed cord. If that happens, your baby needs to be delivered immediately because a prolapsed cord can cut off the blood supply, and thus the oxygen supply to your baby.

- You suffer placental abruption. This is when your placenta starts to separate from your uterine wall, causing a lot of bleeding and risking the oxygen supply to your baby.

- You show signs of uterine rupture. If you're attempting a vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC), the scar on your uterus can open, with potentially dangerous consequences for you and your baby. Your labor team will monitor you closely and be ready to act quickly if needed.

- Stalled labor. It could be that your cervix stops dilating or your baby stops moving down the birth canal. Your labor team will have lots of tips and tricks to move your labor along, but sometimes a cesarean delivery is ultimately needed.

- You have an active genital herpes outbreak. If this happens when you go into labor or when your water breaks (whichever happens first), delivering your baby by c-section will help him avoid infection.

Elective c-section

Elective c-sections are c-sections that aren't medically necessary, and most healthcare providers advise against them. That's because having an unnecessary c-section is riskier for you than vaginal birth. Also, having an elective c-section increases your chances of needing a c-section with future deliveries.

Medical organizations, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), recommend planning for vaginal birth whenever possible. Unless the health of the mother or baby is in danger, ACOG says that the risks associated with a c-section usually outweigh any short-term benefits.

Elective or "maternal request" c-sections are uncommon. Reliable numbers are hard to come by, but most experts estimate fewer than 3 in 100 women request a c-section for their first delivery. Some are afraid of the pain of childbirth, others are worried about complications of vaginal birth like tearing, incontinence and sexual dysfunction, and some feel that a scheduled c-section is easier to plan for than an unpredictable labor and delivery.

If you have any of these concerns, talk to your provider. But because of the risks – including a tougher recovery and a greater chance of complications – be prepared for your doctor or midwife to discourage you from having an elective c-section. However, your provider should be open to an honest conversation about your concerns and needs. Bring them up early in your pregnancy to allow time for an ongoing discussion.

What is a gentle c-section?

A "gentle c-section" is a name for modifications your labor team can make so that your cesarean delivery feels less clinical and more intimate. Depending on the circumstances of your delivery, these may or may not be possible.

Modifications could include:

- A better view of the birth. You can ask to be propped up slightly so you can view the birth through a clear plastic drape, or ask for the drape to be lowered earlier and farther so you can see your baby being born. (A solid drape still blocks your view of the surgical incision.)

- Skin-to-skin contact. Your newborn is placed on your chest (and covered with a warm towel) right after delivery for skin-to-skin contact.

- Less restrictive equipment. Your IV line may be put in your nondominant hand, leaving your dominant hand free to hold your baby. The EKG leads (which track your heartbeat during the surgery) are placed on your back or lower chest instead of your upper chest, so they don't get in the way either.

- Dimmer lighting. Also, reduced noise and background music of your choice.

Although there's not much research on the impact of gentle c-sections, one study found that women had significantly increased satisfaction with the birth experience when gentle c-section techniques were used. Also, immediate skin-to-skin contact helps your baby regulate her body temperature and heart rate.

What is ERAS protocol?

Enhanced Recovery after Surgery (ERAS) protocol is designed to help patients recover more quickly from surgery with fewer complications. Not all hospitals use ERAS, and different hospitals implement it in different ways. For moms having a cesarean delivery, ERAS often means that you'll get oral medications right before your surgery, and long-lasting painkillers in your spinal anesthetic so you have less need for powerful narcotics after surgery. You may be offered non-narcotic pain control methods such as lidocaine patches above your incision and scheduled dosing of ibuprofen and acetaminophen around the clock. You'll be encouraged to get out of bed and try walking within six to eight hours of delivery.

C-section risks

Overall, c-sections are very safe. But a c-section is major abdominal surgery, so it's more likely to cause complications for you and your baby than vaginal birth and to have implications for future pregnancies.

Cesarean delivery risks for moms

Moms who have c-sections are more likely to have:

- An infection in the skin or uterus

- Higher blood loss

- More postpartum pain

- A longer hospital stay and recovery

- Injuries to the bladder or bowel (although this is very rare)

- A reaction to medications or to the anesthesia

- Increased risk of complications in future pregnancies, such as placental abnormalities (placenta previa and placenta accreta)

Cesarean delivery risks for babies

Babies born by c-section are more likely to:

- Have breathing problems than babies delivered vaginally, especially if you have an elective c-section before 39 weeks (which isn't recommended). Note: This is called TTN, or transient tachypnea of the newborn. It usually goes away on its own within the first few days.

- Be temporarily sluggish or inactive after birth (only if you have general anesthesia, which is very rare).

- Be injured accidentally during the surgery (this is also very rare)

Learn more: