This is the second installment in a four-part blog series surveying global intermediary liability laws. You can read additional posts here:

The web of global intermediary liability laws has grown increasingly vast and complex as policymakers around the world move to adopt stricter legal frameworks for platform regulation. To help detangle things, we offer an overview of different approaches to intermediary liability. We also present a version of Daphne Keller’s intermediary liability toolbox, which contains the typical components of an intermediary liability law as well as the various regulatory dials and knobs that enable lawmakers to calibrate its effect.

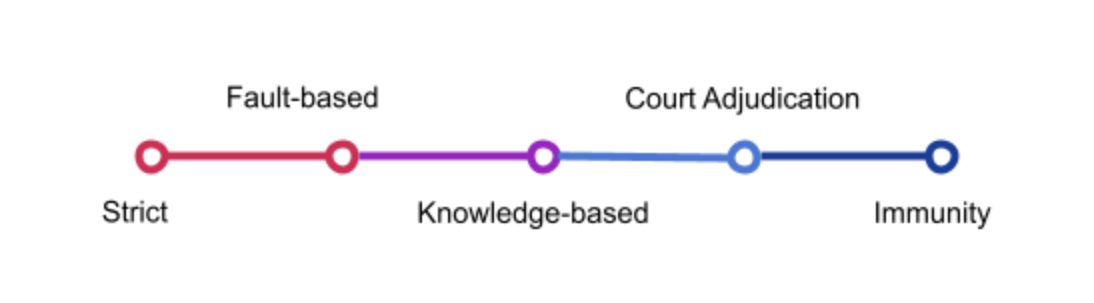

Five-part continuum of Intermediary Liability

Liability itself can be distinguished on the basis of remedy: monetary and non-monetary liability. Monetary liability results in awards of compensatory damages to the claimant, while non-monetary liability results in orders that require the intermediary to take steps against wrongful activities undertaken through the use of their services (usually in the form of injunctions to do or refrain from doing something).

Monetary remedies are obtained after establishing an intermediary’s liability—which ranges from strict, fault-based, knowledge-based, and court adjudicated-liability to total immunity. Various configurations along this spectrum continue to emerge, as regulators experiment with regulatory dials and knobs to craft legislation tailored toward specific contexts.

The categories introduced in this section should be understood as general concepts, as many regulatory frameworks are not clear-cut or allow for discretion and flexibility in their application.

Under strict liability regimes, online intermediaries are liable for user misconduct, without the need for claimants to prove any fault or knowledge of wrongdoing on the part of the intermediary. As liability can occur even if the intermediary did absolutely nothing wrong, strict liability regimes make intermediaries overly cautious; they tend to conduct general monitoring of user content and minimize their exposure to claims by ‘over-removing’ potentially unlawful material. Thus, strict liability regimes heavily burden online speech by encouraging the intermediaries to censor speech, even that which is not harmful.

Fault-based approaches impose liability when the intermediary fails to meet specified ‘due diligence’ obligations or a particular duty of care. For example, intermediaries may be obligated to remove certain types of content within a specific time frame and/or prevent the (re)appearance of it. The UK’s draft Online Safety Bill for example, imposes duties of care which are pegged to certain broad and potentially subjective notions of harm, which are in turn likely to require platforms to engage in general monitoring of user content. Negligence-based liability, as per the UK model, takes a systematic approach to content moderation, rather than addressing individual pieces of content.

The required standard of care under such liability approaches can vary on a continuum from negligence (as established by the actions of a reasonable person) to recklessness (a substantial deviation from the reasonable action). Fault-based liability systems are very likely to effectively require a certain degree of general user monitoring and can lead to systematic over-removal of content or removal of content that may be undesirable, but which is otherwise perfectly legal.

Knowledge-based approaches impose liability for infringing content when intermediaries know about illegal content or become aware of illegal behavior. Knowledge-based liability systems usually operate via notice and takedown systems and thus typically do not require pervasive general monitoring. There are different types of notice and takedown systems, which vary in design and provide different answers to the question about what constitutes an effective notice. What constitutes knowledge on the part of the intermediary is also an important question and not straightforward. For example, some jurisdictions require that the illegality must be “manifest”, thereby evident to a layperson. The EU’s e-Commerce Directive is a prominent example of a knowledge-based system: intermediaries are exempt from liability unless they know about illegal content or behavior and fail to act against it. What matters, therefore, is what the intermediary actually knows, rather than what a provider could or should have known as is the case under negligence-based systems. However, the EU Commission’s Proposal for a Digital Services Act moved a step away from the EU’s traditional approach by providing that properly substantiated notices by users automatically give rise to actual knowledge of the notified content, hence establishing a “constructive knowledge” approach: platform providers are irrefutably presumed by law to have knowledge about the notified content, regardless of whether this is actually the case. In the final deal, lawmakers agreed that it should be relevant whether a notice allows a diligent provider to identify the illegality of content without a detailed legal examination.

The Manila Principles, developed by EFF and other NGOs, stress the importance of court adjudication as a minimum global standard for intermediary liability rules. Under this standard, an intermediary cannot be liable unless the material has been fully and finally adjudicated to be illegal and a court has validly ordered its removal. It should be up to an impartial judicial authority to determine that the material at issue is unlawful. Intermediaries should therefore not lose the immunity shield for choosing not to remove content simply because they received a private notification by a user, or should they be responsible for knowing of the existence of court orders that have not been presented to them or which do not require them to take specific remediative action. Only orders by independent courts should require intermediaries to restrict content and any liability imposed on an intermediary must be proportionate and directly correlated to the intermediary’s wrongful behavior in failing to appropriately comply with the content restriction order.

Immunity from liability for user-generated content remains rather uncommon, though it results in heightened protections for speech by not calling for, greatly incentivizing, or effectively requiring the monitoring of user content prior to publication. Section 230 provides the clearest example of immunity-based approaches in which intermediaries are exempt from some liability for user content—though it does not extend to immunity violations of federal criminal law, intellectual property law or electronic communications privacy law. Section 230 (47 U.S.C. § 230) is one of the most important laws protecting free speech and innovation online. It removes the burden of pre-publication monitoring, which is effectively impossible at scale, and thus allows sites and services that host user-generated content—including controversial and political speech—to exist. Section 230 thus effectively enables users to share their ideas without having to create their own individual sites or services that would likely have much smaller reach.

The Intermediary Liability Toolbox

Typically, intermediary liability laws seek to balance three goals: preventing harm, protecting speech and access to information, and encouraging technical innovation and economic growth. In order to achieve these goals, lawmakers assemble the main components of intermediary laws in different ways. These components typically consist of: safe harbors; notice and takedown systems; and due process obligations and terms of service enforcement. In addition, as Daphne Keller points out, the impact of these laws can be managed by adjusting various ‘regulatory dials and knobs’: the scope of the law, what constitutes knowledge, notice and action processes and ‘good samaritan clauses’. In addition, and much to our dismay, recent years have seen some governments expand platform obligations to include monitoring or filtering, despite concerns about resulting threats to human rights raised by civil society groups and human rights officials.

Let’s now take a brief look at the main tools lawmakers have at their disposal when crafting intermediary liability rules.

Safe harbors offer immunity from liability for user content. They are typically limited and/or conditional. For example, in the United States, Section 230 does not apply to federal criminal liability and intellectual property claims. The EU’s knowledge-based approach to liability is an example of a conditional safe harbor: if the platform becomes aware of illegal content but fails to remove it, immunity is lost.

Most intermediary liability laws refrain from explicitly requiring platforms to proactively monitor for infringing or illegal content. Not requiring platforms to use automated filter systems or police what users say or share online is considered an important safeguard to users’ freedom of expression. However, many bills incentivize the use of filter systems and we have seen some worrying and controversial recent legislative initiatives which require platforms to put in place systematic measures to prevent the dissemination of certain types of content or to proactively act against content that is arguably highly recognizable. Examples of such regulatory moves will be presented in Part Three of this blog series. While in some jurisdictions platforms are required to act against unlawful content when they become aware of its existence, more speech-protective jurisdictions require a court or governmental order for content removals.

Intermediaries often establish their own ‘notice and action’ procedures when the law does not set out full immunity for user-generated content. Under the EU’s eCommerce Directive (as well as Section 512 of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), which even sets out a notice and takedown procedure), service providers are expected to remove allegedly unlawful content upon being notified of its existence, in exchange for protection from some forms of liability. Such legal duties often put users’ freedom of expression at risk. Platforms tend to behave with extra caution under such regimes, often erring on the side of taking down perfectly legal content, in order to avoid liability. It is far easier and less expensive to simply respond to all notices by removing the content, rather than to expend the resources to investigate whether the notice has merit. Adjudicating the legality of content—which is often unclear and requires specific legal competence—has been extremely challenging for platforms.

Intermediaries also exercise moderation by enforcing their own terms of service and community standards, disabling access to content that violates their service agreements. This is seen as “good samaritan” efforts to build healthy civil environments on platforms. This can also enable pluralism and a diversity of approaches to content moderation, provided there is enough market competition for online services. Platforms tend to design their environments according to their perception of user preference. This could entail removing lawful but undesirable content, or content that doesn’t align with a company’s stated moral codes (for example, Facebook’s ban on nudity). As discourse is shifting in many countries, dominant platforms are being recognized for the influential role they play in public life. Consequently, their terms of service are receiving more public and policy attention, with countries like India seeking to exercise control over platforms’ terms of service via ‘due diligence obligations,’ and with the emergence of independent initiatives which aim to gather comprehensive information about how and why social media platforms remove users’ posts.

Finally, the impact of notice and action systems on users’ human rights can be mitigated or exacerbated by due process provisions. Procedural safeguards and redress mechanisms when built into platforms’ notice and action systems can help protect users against erroneous and unfair content removals.

Regulatory Dials and Knobs for Policy Makers

In addition to developing an intermediary liability law with the different pieces described above, regulators also use different “dials and knobs”—legal devices to adjust the effect of the law, as desired.

Scope

Intermediary liability laws can differ widely in scope. The scope can be narrowed or expanded to include service providers at the application layer (like social media platforms) or also internet access providers, for example.

Intervention with content

Does a platform lose immunity when it intervenes in the presentation of content, for example, via algorithmic recommendation? In the US, platforms retain immunity when they choose to curate or moderate content. In the European Union, the situation is less clear. Too much intervention may be deemed as amounting to knowledge, and could thus lead to platforms losing immunity.

Knowledge

In knowledge-based liability models, a safe harbor is tied to intermediaries’ knowledge about infringing content. What constitutes actual knowledge therefore becomes an important regulatory tool. When can a service provider be deemed to know about illegal content? After a notification from a user? After a notification from a trusted source? After an injunction by a court? Broad and narrow definitions of knowledge can have widely different implications for the removal of content and the attribution of liability.

Rules for notice and action

In jurisdictions that imply or mandate notice and action regimes, it is crucial to ask whether the details of such a mechanism are provided for in law. Is the process according to which content may be removed narrowly defined or left up to platforms? Does the law provide for detailed safeguards and redress options? Different approaches to such questions will lead to widely different applications of intermediary rules, and thus widely different effects on users’ freedom of expression.