We begin the introduction to RDFa by using a subset of all the possibilities called RDFa

Lite 1.1 [[rdfa-lite]]. The goal, when defining that subset, was to define a set of

possibilities that can be applied to most simple to moderate structured data markup

tasks, without burdening the authors with additional complexities. Many Web authors will

not need to use more than this minimal subset.

The First Steps: Adding Machine-Readable Hints to Web Pages

Consider Alice, a blogger who publishes a mix of professional and personal articles

at http://example.com/alice. We will construct markup examples to

illustrate how Alice can use RDFa. A more complete markup of these examples is

available on a

dedicated page.

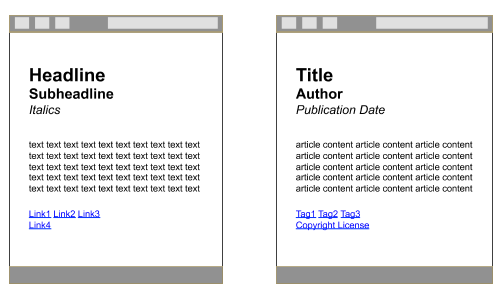

Hints on Social Networking Sites

Alice publishes a blog and would like to provide extra structural information on

her pages like the publication date or the title. She would like to use the terms

defined in the Dublin Core vocabulary [[dc11]], a set of terms that are widely

used by, for example, the publishing industry or libraries. Her blog already

contain that information:

This information is, however, aimed at humans only; computers need some

sophisticated methods to extract it. But, using RDFa, she can annotate her

page to make the structured data clear:

(Notice the markup colored in red: these are the RDFa "hints".)

One useful way to visualize the structured data is:

It is worth emphasizing that RDFa uses URLs to identify just about everything.

This is why, instead of just using properties like title or

created, we use http://purl.org/dc/terms/title and

http://purl.org/dc/terms/created. The reason behind this design

decision is rooted in data portability, consistency, and information sharing.

Using URLs removes the possibility for ambiguities in terminology. Without

ensuring that there is no ambiguity, the term "title" might mean "the title of a

work", "a job title", or "the deed for real-estate property". When each

vocabulary term is a URL, a detailed explanation for the vocabulary term is just

one click away. It allows anything, humans or machines, to follow the link to

find out what a particular vocabulary term means. By using a URL to identify a

particular creation time, for example

http://purl.org/dc/terms/created, both humans and machines can

understand that the URL unambiguously refers to the "Date of creating the

resource", such as a web page.

By using URLs as identifiers, RDFa provides a solid way of disambiguating

vocabulary terms. It becomes trivial to determine whether or not vocabulary terms

used in different documents mean the same thing. If the URLs are the same, the

vocabulary terms mean the same thing. It also becomes very easy to create new

vocabulary terms and vocabulary documents. If one can publish a document to the

Web, one automatically has the power to create a new vocabulary document

containing new vocabulary terms.

Links with Flavor

The previous example demonstrated how Alice can markup text to make it machine

readable. She would also like to mark up the links in a machine-readable way, to

express the type of link being described. RDFa lets the publisher add a "flavor",

i.e., a label, to an existing clickable link that processors can understand. This

makes the same markup help both humans and machines.

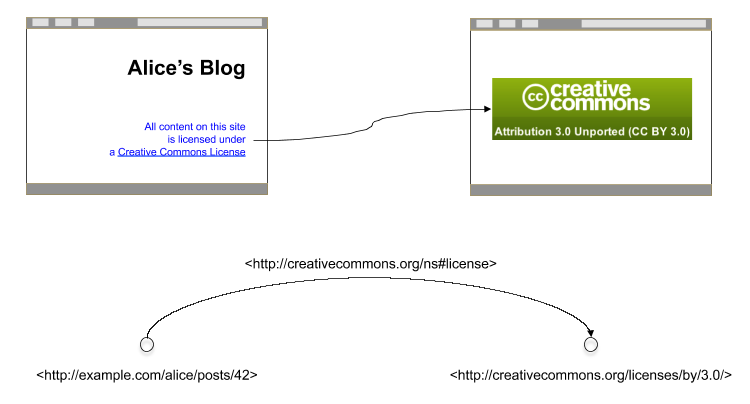

In her blog's footer, Alice already declares her content to be freely reusable,

as long as she receives due credit when her articles are cited. The HTML includes

a link to a Creative Commons [[cc-about]] license:

A human clearly understands this sentence, in particular the meaning of

the link with respect to the current document: it indicates the document's

license, the conditions under which the page's contents are distributed.

Unfortunately, when Bob visits Alice's blog, his browser sees only a plain link

that could just as well point to one of Alice's friends or to her CV. For Bob's

browser to understand that this link actually points to the document's licensing

terms, Alice needs to add some flavor, some indication of what

kind of link this is.

She can add this flavor using again the property attribute. Indeed,

when the element contains the href (or src) attribute,

property is automatically associated with the value of this

attribute rather than the textual content of the a element. The

value of the attribute is the http://creativecommons.org/ns#license,

defined by the Creative Commons:

With this small update, Bob's browser will now understand that this link has a

flavor: it indicates the blog's license:

Alice is quite pleased that she was able to add only structured-data hints via

RDFa, never having to repeat the content of her text or the URL of her clickable

links.

Setting a Default Vocabulary

In a number of simple use cases, such as our example with Alice's blog, HTML

authors will predominantly use a single vocabulary. However, while generating

full URLs via a CMS system is not a particular problem, typing these by hand may

be error prone and tedious for humans. To alleviate this problem RDFa introduces

the vocab attribute to let the author declare a single vocabulary

for a chunk of HTML. Thus, instead of:

Alice can write:

Note how the property values are single "terms" now; these are simply

concatenated to the URL defined via the vocab attribute. The

attribute can be placed on any HTML element (i.e., not only on the

body element like in the example) and its effect is valid for all

the elements below that point.

Default vocabularies and full URIs can be mixed at any time. I.e., Alice could

have written:

Perhaps a more interesting example is the combination of the header with the

licensing segment of her web page:

The full URL for the license term is necessary to avoid mixing vocabularies. As

an alternative, Alice could have also chosen to use the vocab

attribute again:

because the vocab in the license paragraph overrides the definition

inherited from the body of the document.

The vocab attribute references structured data vocabularies, identified using URLs.

RDFa does not limit the form of these URLs or the document formats accessible by de-referencing them;

however users SHOULD aim to use widely shared, conventional values for identifying such vocabularies,

following conventions of case, spelling etc. established by their publishers.

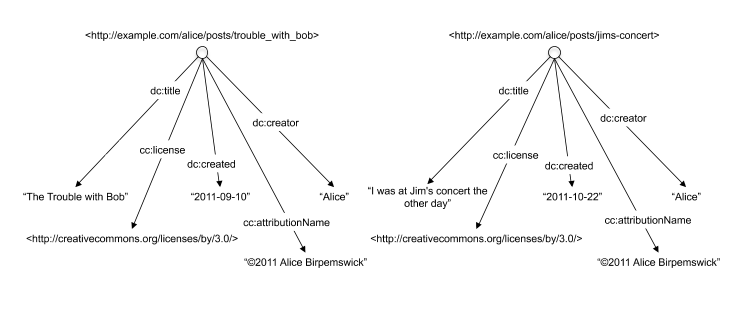

Multiple Items per Page

Alice's blog page may contain, of course, multiple entries. Sometimes, Alice's

sister Eve guest blogs, too. The front page of the blog lists the 10 most recent

entries, each with its own title, author, and introductory paragraph. How, then,

should Alice mark up the title of each of these entries individually even though

they all appear within the same web page? RDFa provides resource, an

attribute for specifying the "context", i.e., the exact URL to which the

contained RDFa markup applies:

(Note that we used relative URLs in the example; the value of

resource could have been any URLs, i.e., relative or

absolute.) We can represent this, once again, as a diagram connecting URLs to

properties:

Alice can use the same technique to give her friend Bob proper credit when she

posts one of his photos:

Notice how the innermost resource value,

http://example.com/bob/photos/sunset.jpg, "overrides" the outer

value /alice/posts/trouble_with_bob for all markup inside the

containing div. Once again, here is a diagram that represents the

underlying data of this new portion of markup:

Exploring Further: Social networks

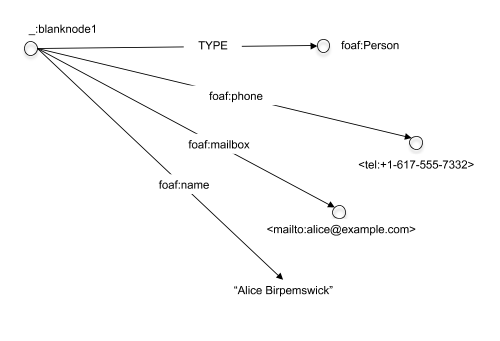

Contact Information

Alice would also like to make information about herself, such as her email

address, phone number, and other details, easily available to her friends'

contact management software. This time, instead of describing the properties of a

web page, she's going to describe the properties of a person: herself.

Alice already has contact information displayed on her blog.

The Dublin Core vocabulary does not provide property names for describing contact

information, but the Friend-of-a-Friend [[foaf]] vocabulary does. Alice therefore

decides to use the FOAF vocabulary. As a first step, she declares a FOAF

"Person". For this purpose, Alice uses typeof, an RDFa attribute

that is specifically meant to declare a new data item with a certain type:

Alice realizes that she only intends to use the FOAF vocabulary at this point, so

she uses the vocab attribute to simplify her markup further (and

overriding the effects of any vocab attributes that may have been

used in, for example, the body element at the top).

Then, Alice indicates which content on the page represents her full name, email

address, and phone number:

Note how Alice did not specify a resource like she did when adding

blog entry metadata. But, if she is not declaring what she is talking about, how

does the RDFa Processor know what she's identifying? In RDFa, in the absence of a

resource attribute, the typeof attribute on the

enclosing div implicitly sets the subject of the properties marked

up within that div. That is, the name, email address, and phone

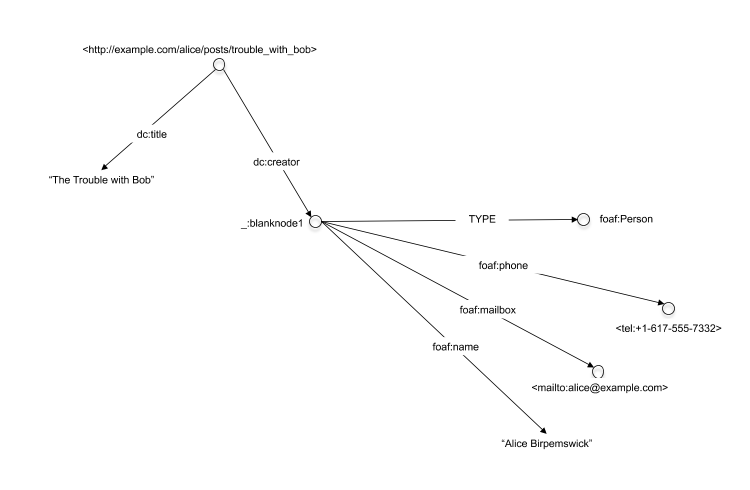

number are associated with a new node of type Person. This node has

no URL to identify it, so it is called a blank node as shown on the

figure:

Describing Social Networks

Alice continues to mark up her page by adding information about her friends,

including at least their names and homepages. She starts with plain HTML:

First, Alice indicates that the friends she is describing are people, as opposed

to animals or imaginary friends, by using again the Person type in

typeof attributes.

Beyond declaring the type of data we are dealing with, each typeof

creates a new blank node with its own distinct properties. Thus, Alice can

indicate each friend's homepage:

Alice would also like to improve the markup by expressing each person's name

using RDFa, too. That can be done by adding a separate span element

and the relevant property:

Alice is happy that, with so little additional markup, she's able to fully

express both a pleasant human-readable page and a machine-readable dataset.

Alice is a member of 5 different social networking sites. She is tired of

repeatedly entering information about her friends in each new social networking

site, so she decides to list her friends in one place-on her website, combining

it with her own FOAF data. With RDFa, she can indicate her friendships on her own

web page and let social networking sites read it automatically. So far, Alice has

listed three individuals but has not specified her relationship with them; they

might be her friends, or they might be her favorite 17th century poets. To

indicate that she knows them, she uses the FOAF property foaf:knows:

With this, Alice could describe here social network:

Repeated Patterns

We have seen, in a previous section, how Alice can use RDFa to include Creative Commons statements on her blog. However, the solution in that section assigned these statements to the whole page, and not to individual blog items. This may be an issue if the page includes multiple items. Indeed, Alice may be forced to repeat the relevant statements like this:

which may be tedious and error prone.

HTML+RDFa introduces the notion of "Property copying" to alleviate this situation. Using this feature Alice can "collect" a number of statements as a pattern, and refer to that pattern from other parts of the page. This is done using the magic property rdfa:copy and the magic type rdfa:Pattern as follows:

(Alice may choose to use CSS to make the CC statements invisible on the screen if she wants.) The effect of this structure is to, conceptually, "copy" all the RDFa statements appearing in the pattern to replace the link element, yielding the following structure:

Internal References

Alice may want to add her personal data to her individual blog items, too. She

decides to combine her FOAF data with the blog items, i.e.:

The structured data she generates looks like this:

Unfortunately, this solution is not optimal in two respects. First of all, notice

that Alice had to use the full URI for the creator property: this is

because the vocab attribute is used to set the FOAF terms, i.e., the

simple creator value would have been misinterpreted. We will come back

to the issue of using several vocabularies in another

section below.

The other issue is that Alice would like to design her Web page so that her personal

data would not appear on the page in each individual blog item but, rather, in one

place like a footnote or a sidebar. I.e., what she would like to see is something

like:

If the FOAF data were included in each blog item, Alice would have to create a

complex set of CSS rules to achieve the visual effect she wants.

To solve this, Alice decides to make use of the structure she already used for her

FOAF data but, this time, assigning it a separate URI using the resource

attribute:

It is actually considered as a good practice to use real URIs whenever possible,

i.e., Alice's new alternative should be preferred in general. Indeed, if a real URI

is used, then it becomes possible to unambiguously refer to that particular piece of

information, whereas that becomes more complicated with blank nodes.

The resource="#me" markup (which, by the way, also presupposes that the target is in the

same HTML scope) is a FOAF convention: the URL that represents

the person Alice is http://example.com/alice#me. It should not

be confused with Alice's homepage, http://example.com/alice. Of course,

Alice could have used a different URI if, for example, her blog and her personal

homepage were kept separate; e.g., she could have used

resource="http://alice.example.com/alice/home#myself" instead of

resource="#me".

Using the explicit URI for her FOAF data Alice can add a direct reference to the blog

item using again the resource attribute:

The resource attribute appears, in this case, together with

property on the same element: in this situation

resource indicates the "target" of the relation. Usage of this attribute

allows Alice to "distribute" the various parts of her structured data on her page.

What she gets is a slightly modified version of the previous structure, where the

only difference is the usage of an explicit URI instead of a blank node:

Using this approach, it becomes very easy to also add references to the same data from different blog posts:

Leading to the following structure:

Combined with property, the resource attribute plays

exactly the same role as href, already used for "links with flavor",

except that it does not provide a clickable link to the browser like

href does. Also, the resource attribute can be used on

any HTML element, as opposed to href whose usage is restricted,

in HTML, to the a and link elements.

There is a similarity between this issue and its solution and the issue and the approach taken in the section on property copying. There is, however, a subtle but important difference between the two. The solution using the resource attribute introduces a new node in the graph, as shown on Figure 12, whereas copying the properties does not. Which of the two approaches should be adopted is often based on the vocabulary that is used.

Using Multiple Vocabularies

The previous examples show that, for more complex cases, multiple vocabularies have

to be used to express the various aspects of structured data. We have seen Alice

using the Dublin Core, as well as the FOAF and the Creative Commons vocabularies, but

there may be more. For example. Alice may want to add vocabulary elements defined by

search engines on their schema.org site [[schema]].

Alice can use either full URLs for all the terms, or can use the vocab

attribute to abbreviate the terms for the predominant vocabulary. But, in some cases,

the vocabularies cannot be separated easily, which means that the usage of

vocab may become awkward. Here is, for example, the kind of HTML she

might end up with:

Note that the schema.org and the Dublin Core terms are intertwined for a specific

blog, and it becomes an arbitrary choice whether to use the vocab

attribute for http://purl.org/dc/terms/ or for

http://schema.org/. We have seen the same problem in a previous section when FOAF and Dublin Core terms were

mixed.

To alleviate this problem, RDFa offers the possibility of using prefixed

terms: a special prefix attribute can assign prefixes to represent URLs

and, using those prefixes, the vocabulary elements themselves can be abbreviated. The

prefix:reference syntax is used: the URL associated with

prefix is simply concatenated to reference to create a full

URL. (Note that we have already used this convention to simplify our figures.) Here

is how the HTML of the previous example looks like when prefixes are used:

The usage of prefixes can greatly reduce possible errors by concentrating the

vocabulary choices to one place in the file. Just like vocab, the

prefix attribute can appear anywhere in the HTML file, only affecting

the elements below. prefix and vocab can also be mixed, for

example:

An important issue may arise if the html element contains a large number

of prefix declarations. The character encoding (i.e., UTF-8, UTF-16, ASCII, etc.)

used for an HTML5 file is declared using a meta element in the header.

In HTML5 this meta declaration must fall within the first 512 bytes of the page, or

the HTML5 processor (browser, parser, etc.) will try to detect the encoding using

some heuristics. A very "long" html tag may therefore lead to problems.

One way of avoiding the issue is to place most of the prefix declarations on the

body element.

Repeating properties

The previous example, whereby the Dublin Core and the schema.org vocabularies are

used within the same blog post, raises another issue. It so happens that not only

Dublin Core, but also schema.org has a property called creator.

Because RDFa uses URIs to denote properties that, by itself, is not a problem.

However, if Alice wants to use both these properties in the same blog

post (e.g., because she wants search engines to manage her blog post but, at the

same times, she wants Dublin Core aware applications, like catalogs, to handle

her blog post, too) this is what she may have to do:

Which is a bit awkward. Fortunately, RDFa allows the value of a

property attribute to be a list of values, i.e., she can also write:

yielding the structure:

Similarly to property, typeof also accepts a list of values. For example,

schema.org also has a notion of a Person, similar to FOAF; Alice may choose to use both:

Default Prefixes (Initial Context)

A number of vocabularies are very widely used by the Web community with

well-known prefixes—the Dublin Core vocabulary is a good example. These common

vocabularies tend to be defined over and over again, and sometimes Web page

authors forget to declare them altogether.

To alleviate this issue, RDFa introduces the concept of an initial

context that defines a set of default prefixes. These prefixes, whose list

is maintained and regularly updated by the W3C, provide a number of pre-defined

prefixes that are known to the RDFa processor. Prefix declarations in a document

always override declarations made through the defaults, but if a web page author

forgets to declare a common vocabulary such as Dublin Core or FOAF, the RDFa

Processor will fall back to those. The list of default prefixes are available on the Web for

everyone to read.

For example, the following example does not declare the dc:

prefix using a prefix attribute:

However, an RDFa processor still recognizes the dc:title and

dc:creator short-hands and expands the values to the corresponding

URLs. The RDFa processor is able to do this because the dc prefix is

part of the default prefixes in the initial context.

Default prefixes are used as a mechanism to correct RDFa documents where authors

accidentally forgot to declare common prefixes. While authors may rely on these

to be available for RDFa documents, the prefixes may change over the course

of 5-10 years, although the policy of W3C is that once a prefix is defined as

part of a default profile, that particular prefix will not be changed or

removed. Nevertheless, the best way to ensure that the prefixes that document

authors use always map to the intent of the author is to use the

prefix attribute to declare these prefixes.

Since default prefixes are meant to be a last-resort mechanism to help novice

document authors, the markup above is not recommended. The rest of this document

will utilize authoring best practices by declaring all prefixes in order to make

the document author's intentions explicit.