Before Bear Lodge, I’d never actually taken an Uber. Part of the reason was circumstantial – I’ve never been much of a traveler – but I’d also made a promise to Dr. Safar, my old colleague at the community college. Dr. Safar emigrated with his wife from Syria ten years ago after she accepted a cardiology residency at Mercy Hospital. He was an anthropologist in Syria but in Pittsburgh, for a time, he was a taxi-driver. “Cliché, I know,” he told me once during our smoke break. “But that’s what a lot of us did when we first arrived. And I’d do it again if I had to. The firm took care of me. You should always take a taxi, Kate, not one of those internet cars. Much better for the drivers.” He stopped driving a taxi when he and wife had saved enough to move across the river and eventually he became my office mate at Wallace Community College, sharing the sunless warren of desks reserved for adjunct instructors.

Despite his wife’s profession, Dr. Safar was an unapologetic smoker and we spent most afternoons together at an uncomfortable concrete picnic table between the faculty parking lot and the administration building, killing time. Because the college paid us by the course – and quite poorly at that – we resented spending the long stretches of time between our 8am classes and 3pm classes in our office and rotated between the picnic tables and our small cafeteria. Without a hint of irony, Dr. Safar suggested the time outdoors would be “good for our health, Kate, with the fresh air,” and, weather permitting, we stuck to our routine. He’s gone now. His wife jumped at the chance to take a senior surgical position in Canada after the election, and I guess I don’t blame her.

Continue reading “BEAR LODGE, a ghost story about late-capitalism”

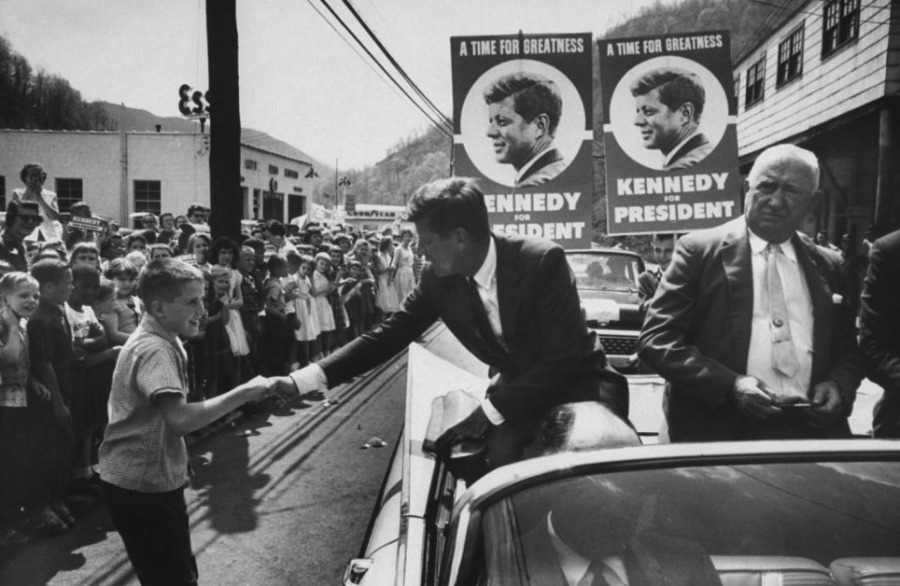

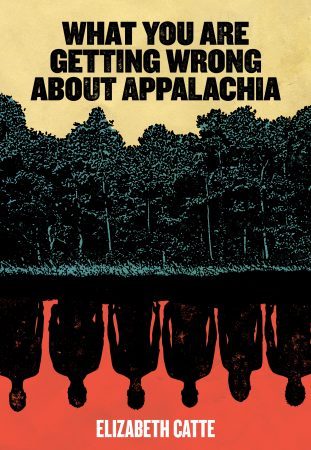

My book taking on Trump Country narratives, J.D. Vance, and the amnesia surrounding Appalachia’s progressive side is now available to pre-order through the wonderful folks at Belt. Place your order before November and you’ll automatically receive a signed copy.

My book taking on Trump Country narratives, J.D. Vance, and the amnesia surrounding Appalachia’s progressive side is now available to pre-order through the wonderful folks at Belt. Place your order before November and you’ll automatically receive a signed copy.