In Community, Design, Twitter on

27 October 2013

Say you’re a supervillian. Your goal is not to take over the world, but to create more unpleasantness. So you set out to create a device that would ensnare normal, rational people and turn them into ranting lunatics. What would your Argument Machine look like? How would it work?

(Note that I mean “argument” not in terms of academic debate, which is healthy, but in the everyday “unproductive, unpleasant, angry fight” sense of the word.)

First, the machine would have to be online, so it could reach the maximum amount of people with the least amount of construction. People feel protected online, like they do in cars, so they’re more willing to fight. But it shouldn’t be just a website. It would also have to be an app on all the major platforms for maximum reach.

All arguments have a beginning, so we’ll create a tool for people to post their thoughts. This should be as easy as possible, so people do it without thinking too deeply. Forethought is the enemy of a nasty argument.

Arguments tend to fizzle out quickly if the participants are able to make a fully fleshed-out thought, so we’ll limit every thought to a ridiculously small size, say 140 characters. Brevity may be the soul of wit, but it’s also the root of misunderstandings.

We’ll then take those short thoughts and present them immediately to the audience, without any ability to edit them after the fact. We’ll even create a “reply” affordance that seems like it’s private, but we’ll actually show the reply publicly. Nothing creates a fight faster than in-group language overheard by the out-group.

To maximize negative reactions, we’ll design the presentation of these short thoughts to create annoyance. Tests have shown that information coming in too fast can create anger and defensiveness, just like someone interrupting you in real life, so we’ll make everything as fast and interruptive as possible. We’ll also pack the app with lots of notifications, so we can make people’s pockets buzz every time someone mentions them. Just like the electric shocks we used on those lab rats.

If someone isn’t receiving enough of these short thoughts to overwhelm them, then we’ll blanket them with suggestions of other people they should be hearing from, to encourage all new members to quickly reach an overwhelmed state.

With enough people, and enough short thoughts, arguments are sure to occur. When they do, we’ll add heat to them by making sure everyone can see the individual thoughts outside of the argument’s participants. Nothing like a hooting crowd to make a bad situation worse. We’ll even add a tool to allow others to repeat the thoughts to a wider network (out of context, of course). The more people who pile in, the longer the argument will last, the more people will participate.

If everything goes well, the mainstream media will start monitoring these thoughts, so that they can embarrass famous people when they speak out of turn. We’ll even create an way for people to embed these thoughts on other sites so that they remain even after the original poster deletes them. Gotcha!

Nothing is better at creating new arguments than other arguments, so once we reach a critical mass, avoiding arguments will be impossible. Now all we have to do is sit back and practice our supervillian laugh. And maybe go public.

+

I think you get my point by now. Yes, I’m talking about Twitter.

I’m not saying that Twitter was designed to create arguments. I’m just saying that, if you set out to create an Argument Machine, it’d come out looking a lot like Twitter.

I think Twitter is awesome. As of today, I’ve tweeted more than 16,000 times. It’s the community tool I use more than any other. But with Twitter preparing to IPO and monetize all of us, I worry about the health of the community the tool produces.

If Twitter cared about avoiding arguments, there are so many things they could do: remove the outdated character limit, let us edit tweets, create progressive circles of privacy, don’t let retweets out of our networks, slow the whole thing down, and encourage smaller communities. But they’re not going to do any of those things because the financial pressure points in exactly the opposite direction: more users, more tweets, faster and faster. Who cares if they’re fighting?

Well, I do. I want Twitter to succeed. But every time I see some innocuous tweet spawn another long, bile-filled thread of awfulness, I become less interested in tweeting. I know, arguments will always happen, online and off. But the design of the tools we use can encourage or inhibit this human tendency, and I’m afraid Twitter is falling very far into the “encourage argument” side of things. And I’m not alone.

Where will we go when we all tire of getting yelled at on Twitter? What would a tool designed to create a harmonious exchange of interests and ideas even look like? I’m confident we’ll find out eventually, but I seriously doubt its logo will be a little blue bird.

+

This post also appears on Medium.

In Cute-Fight, Startups, Tonx on

22 September 2013

Or: I have some awesome job news.

You learn things when you start a company. When I cofounded 8020, I learned to ask the difficult questions. When I cofounded JPG Magazine with my wife, I learned how important it was for everyone to be in charge of something. And when I founded Cute-Fight, I learned … a lot.

Cute-Fight taught me that there’s a certain skill set required to raise venture capital, and it’s not one I really want. It taught me that I really do like managing people, especially when they’re as talented as that team. It taught me that running a startup is mostly about setting priorities and convincing people that they’re the right ones.

But most of all, running Cute-Fight reminded me of some things I already knew but had gotten lost somewhere along the way. It reminded me that I really love making products for specific communities, nurturing the garden, and seeing what blooms. And it reminded me that I really like writing.

At Cute-Fight, with the design, illustration, and engineering all in excellent hands, I did whatever was left over. And most of what was left over was writing. Writing the newsletter, responding to member emails, crafting every word that appeared on the website.

It’s funny that a guy with a journalism degree and 20 years of work in and around the publishing industry should have to rediscover his love of writing, but there you go. I think it just got buried under lofty terms like “experience design” and “content strategy” and “community management.” All those things, at their core, are about putting the right words in the right order.

So when it became clear that Cute-Fight was not going to pay my bills, and, worse, that I had gone into debt chasing the startup dream, I started looking for work with increasing desperation. I made some mistakes in this process. Mistakes I feel bad about now. Suffice to say, it was a rough time. But this is a story with a happy ending.

A couple years ago, Nik and Tony started a company called Tonx. The idea was simple: get the best coffee beans from all over the world, expertly roast them, and mail them to subscribers every two weeks.

I’d been a Tonx subscriber since the start, and Nik and Tony had become internet friends. Tonx was the first company to sponsor a Cute-Fight venue, and while we were working that out, I was impressed with how smart, generous, and passionate they were.

In a couple visits to San Francisco, Nik and Tony told me about their plans for the future of the company. It hit me in a flash: Tonx is a biweekly magazine published in bean form. What JPG Magazine was to photography, Tonx is to coffee.

“What you need,” I said excitedly, “is someone who can write and edit, with experience in publishing and community building.” They both smiled and asked me if I knew anyone like that. Only then did it sink in that they were offering me a job.

I’ve been working as Tonx’s Editor in Chief for a couple months now, and it’s been a joy. It’s all the parts of what I loved about doing Cute-Fight – writing, community, product – with an amazing team of engineers, coffee pros, and a rapidly growing member base of devoted (and caffeinated) customers.

Coffee maintains a special place in creative culture. When I think back to my happiest moments, coffee was always nearby. It’s a daily morning ritual that I share with millions of other people. It’s a connective thread that ties our lives together. With such a hot, emotional product, there’s no end to the collaborative projects we could do.

So we’ve got plans. Big plans. I can’t go into detail yet, but if you know me and my work, you may have a general idea. You can see the humble beginnings in The Frequency, where we’re adding weekly travelogues, reviews, and photo essays – not just about coffee but coffee culture at large. They’re the right words, in the right order, as much as we can.

So we’ve got plans. Big plans. I can’t go into detail yet, but if you know me and my work, you may have a general idea. You can see the humble beginnings in The Frequency, where we’re adding weekly travelogues, reviews, and photo essays – not just about coffee but coffee culture at large. They’re the right words, in the right order, as much as we can.

One of the most challenging things about being a startup CEO that nobody tells you is that, when it’s over, it’s terrifying to go back to being someone else’s employee, working on someone else’s vision. Once you sit in the big chair, every other chair feels too small.

My only advice for someone in that situation is this: use the experience to figure out which parts are required for your happiness and try to find that somewhere else. If you’re extremely lucky, you’ll find a team of talented people working on something awesome who need someone in exactly that role. I was that kind of lucky and I’m so incredibly grateful I can’t even describe it.

If you love coffee, sign up for Tonx. You won’t regret it. And I’ll be on the other end of that line with the rest of the team, working on some exciting stuff for you.

Ever forward!

In Cute-Fight, Startups on

21 August 2013

About a year ago, when I introduced Cute-Fight, I shared the story of telling my dad about it. He asked if people would really fight each other’s pets to see who’s cutest. I ended the post with, “We’ll see.” Now I know the answer.

About a year ago, when I introduced Cute-Fight, I shared the story of telling my dad about it. He asked if people would really fight each other’s pets to see who’s cutest. I ended the post with, “We’ll see.” Now I know the answer.

Yes, they would.

In the year since Cute-Fight started, first in private alpha and then in public December, about 6,000 brave souls became members, created 3,000 fighter profiles, uploaded 15,000 photos, fought 20,000 fights, which collected over 150,000 votes.

These are respectable numbers, and I’m proud of them. If I could buy every one of those members a beer, I would.

But they’re not the kind of numbers investors or sponsors got excited about. Investors wanted to see a growth curve that looked like Twitter year three, but ours looked like Twitter year one. And while a few awesome sponsors came on board to create venues, the activity was just not enough for me to sell. I dropped the prices and added more time for us to hit the numbers I promised, ultimately giving them value for their money, but it was clear the business model wasn’t working.

In March, with the small amount of friends and family money gone, my savings dry, and my debt growing, I had to stop paying the team. To their credit, and with my everlasting thanks, they kept on working as long as they could. But a few months ago, we all realized we’d have to look elsewhere for income.

There are startup hero stories aplenty in San Francisco. Tales of founders going against the odds, persevering in the face of obscurity, and then finally being rewarded with fame and fortune. But what they don’t tell you is that 99% of those stories end with the business shutting down and the founder moving away or getting a job or worse. Most of the time, it doesn’t work. And though it pains me to say it, Cute-Fight is one of those 99%. It didn’t work as a business.

So, dad, yes, people will do that. Just not enough of them.

So what now? Cute-Fight will stay online, as it is, for now. It still works, it’s still fun, and it’s still being used by its small community. It doesn’t cost a ton of money to host, and I don’t want to see all that hard work just go offline. Plus, I can’t help but hope the game will see slow and steady growth. Maybe without the pressure of fundraising, it can grow at its own rate. But we’re not actively working on it anymore, and if something breaks that I can’t fix I’ll have to just take it down.

The biggest bummer for me is all the things we had planned that we never got to do. For posterity, here’s the top of the list.

- Retired Champions – Sadly, sometimes pets die. We had a plan to handle this. The manager would “retire” the fighter. All retired fighters were listed as champions and got a special profile and their photo on the wall of honor.

- Themed Fights – Instead of just fighting to see who’s cutest, managers could challenge each other for battles on other themes – laziest dog, scariest cat, best driver, anything.

- Parades – We had sketched out other games that were more collaborative. My favorite was parades, which were collections of photos on a theme, the page animating to show the photos moving down a street.

- Teams – You could band together with all your favorite fighters and form a team. Which of course leads to…

- Brackets – Organized events with sponsored prizes where one fighter could be proclaimed champion. The Superbowl of Cute.

- Physical products – Real trophies for winners, print-on-demand books and posters, dog shirts and cat collar charms.

And then there’s all the obvious stuff we just never got to. A weekly activity mail. Notifications of comments on the homepage. Better tools for fans and people without pets. Better tools for adoption agencies. And on and on.

In the end, being a startup founder is about prioritizing stuff. I think I set good priorities, but there’s always that nagging feeling that any one of those things might have lit a match that led to a bigger bang. The annoying thing is not knowing.

The last few months have been some of the most depressing of my entire career. Having something you believe in so deeply, something you convinced your friends and family to invest their time and money in, something you spend every waking hour thinking about, and watching it flounder is like pounding your head into a mirror. It hurts, it shatters your vision, and you have no one to blame but yourself.

I think next time I might pay a little closer attention to my dad’s early questions.

The good news is that I’m coming out the other end of it now, and I have something I’m really excited to tell you about. More on that soon.

For now, I just want to thank the core team, Devin Hayes, James Goode, and Chris Bishop. You guys turned a silly idea into the funnest, weirdest, most joyful thing I’ve ever worked on. I can’t wait until we all get to work together again. (And if anyone out there is looking for the best designer/frontend coder I’ve ever worked with, go see James. He’s got some time open now.)

I also want to thank Patrick Mahoney of the SF MusicTech Fund for his early and astonishing support. I’ll never forget it. I’ll also never forget the people who helped with their advice and introductions, especially Chris Tacy and Janice Fraser. And, of course, thanks to my wonderful wife, Heather Champ, who loved and supported me all the way through.

Special thanks to our sponsors, Shibashiba, Twitterrific, and Tonx for their support. We couldn’t have done it without you. I heartily recommend you give them your money.

And finally, I want to thank every one of our awesome members. We built this for you and we’re so glad you liked it. Meeting your pets and seeing your photos was the best part of this whole adventure. I’m truly grateful for your participation.

Ever forward,

— Derek

In Fertile Medium on

26 June 2013

Hint: Do it like Kickstarter, not Paula Deen.

If you’re human, eventually you’ll have to apologize for something. How you communicate that apology will say more about you, your company, and your community than anything else.

Two high profile apologies hit the web today, one from Kickstarter and the other from Paula Deen. Without getting into the specifics of what they were each apologizing for, they make for two fascinating case studies in how to apologize online.

(Yes, Kickstarter is a company and Paula Deen is a person, but in this context, they’re both corporations with angry communities, and their businesses hang in the balance.)

With today’s examples in mind, here’s the Fertile Medium recipe for apologizing online.

Step 1: Restate the problem.

I know, you’re embarrassed. You probably don’t want to remind everyone of the thing that pissed them off. But apologies online take on a life of their own, bringing in people who are unfamiliar with the details. Restating the problem not only gets everyone on the same page, it also shows that you understand what you did wrong.

Kickstarter begins their post with a brief summation of what happened, complete with links so that the interested reader can follow up for more information. Paula Deen skips this step, only referring to “inappropriate language,” leaving those unfamiliar with the situation to imagine the worst.

Step 2: Own it.

Before you do anything else, prove that you know what you did. This shows that you’re not just apologizing because someone told you that you have to – you’re apologizing because you have genuine remorse.

Kickstarter says, in a paragraph all by itself, “We were wrong.” It’s a sharp, frank admission. Paula Deen says she “made plenty of mistakes along the way” but doesn’t say if she thinks this was one of them. She says “I apologize,” but never simply says “I was wrong.”

Step 3: Say you’re sorry.

Now that you’ve demonstrated your understanding of the situation, your apology will have more meaning. Never, ever follow the word “sorry” with the word “if” – as in: “I’m sorry if you’re offended.” That only shows that you don’t really mean it.(Nobody did this here, I just hate that.)

Both Kickstarter and Paula Deen did this part, but it was basically all Paula Deen did, which is why her apology has so little weight.

Step 4: Explain what went wrong.

This is a tricky maneuver. Do it right and your explanation will add valuable details that help the reader better understand your perspective. Do it wrong and it’ll sound like defensiveness.

Kickstarter did this part very well. They explain why they acted when they did, and shared more detail about their internal process. I especially like that they admitted that they’re “biased towards creators.” As a platform for creation, of course they are.

Paula Deen didn’t do this at all. She could have said, “You know, I grew up in Georgia in the ’50s and let me tell you, I heard some horrifying stuff. I’m sad to say, some of that language and some of those jokes got stuck in my head. I’m ashamed that I repeated them.”

Explaining what went wrong doesn’t mean excusing it. But, if handled correctly, it can serve to humanize the apologizer.

Step 5: Make a vow.

Explaining what happened shows you understand the past, making a vow shows you’ve thought about the future. Make a promise to not repeat this mistake. Do it at a permanent URL and be clear about what you’re promising. You’ll be judged by how you keep your word.

Kickstarter also did this with aplomb. They took direct action, explained why, provided proof, and changed their guidelines to ensure it doesn’t happen again. Paula Deen … didn’t. She apologized in multiple videos, some of which kept disappearing throughout the day, adding an unnecessary layer of aggravation to the whole ordeal.

Step 6: Make amends.

Prove you get it.

Apologizing isn’t just about words, it’s about deeds. Do something to prove that you understand the magnitude of your mistake.

In Kickstarter’s case, they made a large donation to a nonprofit that’s directly related to the issue at hand. They put more money into the nonprofit than was involved in the mistake. This shows they understand the value of their community goodwill.

Paula Deen, again, didn’t do anything of the sort.

Step 7: Apologize again.

Apologies don’t have a 1:1 ratio with mistakes. You may have to apologize more than once. Don’t like apologizing? Pick a career that doesn’t involve other people. Apologize and keep apologizing as long as you have to.

Finally, it’s interesting to note that Kickstarter apologized in text and Paula Deen did it in a video. While this could be because her primary relationship with her audience is in video, it also may have been an attempt to humanize her.

Apologies via video is a dangerous strategy. If the video is too polished (as her first one was), it can seem inauthentic. If the video is too amateur (as the second and third ones were), it looks like you’re not taking it seriously. Perhaps, if she’d written it instead, she could have given it a bit more thought. Changing her usual medium from video to text would have shown a degree of consideration that the videos didn’t.

Mistakes are inevitable. How you respond is what defines you. Use the apology opportunity to reinforce your core values.

If you do it right, you’ll create a stronger bond with your community, one that will earn you the benefit of the doubt the next time you screw up.

Do it wrong and you may just lose your job.

Fertile Medium is an advice column for people who live online. Each edition tackles a topic or question from you about building social spaces online. Want to ask a question? Tweet to @fertilemedium or call (415) 286-5446 and leave a message.

In Business, Elsewhere, Flickr on

23 May 2013

The new Flickr: Goodbye customers, hello ads

Flickr didn’t actually explain itself. It took away a core part of its original product (unlimited uploads), replaced it with a free version and an expensive and limited upgrade, and declared it “spectaculr,” and hoped that we’d be too distracted by big photos and purposeful misspellings to notice.

Yeah, I’m not a fan.

In Cute-Fight on

8 March 2013

Over at Cute-Fight, we’ve completely revamped the fighter profile pages. Check out Bug’s page.

Over at Cute-Fight, we’ve completely revamped the fighter profile pages. Check out Bug’s page.

We’ve been working on this update for months. The goal is to make our pets look awesome, as well as make these pages a fun place to visit for all. Here are some of the notable features.

When your fighter is in a fight, one of our specially trained pilots flies by with a banner tell the world.

The main area is now designed to match the cards that appear in fights, showing your fighter’s bio, photo, and other information. If you’re the manager, you get some special stats and features. And note that little orange bump on the right side. I wonder what it does?

Fans appear! You can now see all the members who are fans of your fighter, right on the profile.

And finally, the trophy case and badges box, where your fighter proudly shows off all their winnings.

We’re really proud of this update and hope you dig it, too. And if you have a pet you haven’t yet added to Cute-Fight, what are you waiting for? Bring ‘em on!

In Geek, Twitter on

8 February 2013

I’ve been using Twitter since 2006, and thanks to their new archive feature, I was recently able to download all of my tweets. I’ve blocked a lot of people over the years – I love my Magic Button – and occasionally I’ll make a mental note of why I did it. Here’s the list so far.

- Replying with “That’s what she said.”

- Shotgun replies (like 10 in a row).

- Being the pope.

- Being Charlie Sheen.

- Being my mom.

- Pedantics. (IE, anyone who knows that should be “pedantism.”)

- Asking me something you could have found in Google in two seconds.

- Repeatedly replying to tweets with your URL.

- Taking me too seriously.

- Demanding that I take you too seriously.

- Anything about Jesus.

- Anything about Gangnam style.

- “PLZ RETWEET!!!”

- Replying with a URL and nothing else.

- Mindless flag-waving “more patriotic than thau” bullshit.

- Hitler jokes.

- Making me explain the joke.

- Supporting Prop 8 (AKA bigotry).

- Bad taste in TV.

- Bad taste in music.

- Bad taste in men.

- Apostrophe abuse.

- Telling me not to be grumpy when I am obviously grumpy.

- Becoming the mayor of anything that’s not a city.

- Unironic use of “LOL.”

- Starfucking.

- Excessive punning.

- “Get a hybrid.”

- I was having a bad day.

- You were having a bad day.

So if I ever blocked you on Twitter, it’s probably one of those things. Or maybe something entirely new. Remember, it’s not you, it’s me. I just think we should follow other people right now. I only want you to be happy.

+

SEE ALSO: Press the Magic Button! My “one strike” rule for Twitter/Flickr and why you shouldn’t be offended when someone blocks you.

AND: Twitter for Adults.

In Business, Cute-Fight, Internet, Startups on

19 December 2012

Yesterday I posted a discombobulation of the “If you’re not paying for the product, you are the product” truism. Judging from the feedback, I hit a nerve.

Today I realized that I broke one of my own rules. Don’t just complain, propose a solution. So here goes.

Instead of telling people “you are the product,” which creates a feeling of inevitability and powerlessness, let’s say this: “If you don’t know how a startup will make money, neither do they.”

This, I hope, will remind people that the business plans of the startups they use are, indeed, their business. They should find out how the company is making money now and what their plans are in the future. They can then make an educated decision whether to participate or not. They can also judge the company by how well they keep their word.

It’s also a clear message to startups: your business plan cannot be secret anymore. People are too smart for that, too tired of getting burned, too wary of losing their contributions when a startup dies, and too annoyed by sudden changes to the terms. Communicate your business plan from the start and you’ll avoid a thousand problems down the road.

It’s a sign of the times that when I told people about Cute-Fight, their first question was usually, “How will it make money?” That never happened back in the day.

So we’ve had an answer in our FAQ since day one. In a nutshell, it’s sponsored venues. We did the hard work to have examples like this and this shortly after launch. That way, when people asked, we could point to a real example on the website.

Now, of course, this is not the only way we plan to make money. We’ve got other ideas that we should talk about sooner than later. But the point is to have an answer and make it public.

Many startups are afraid of this kind of disclosure. There was a time when you wanted to keep these plans a secret. But times are changing. People expect to know. And if we want them to trust us, we’ve got to tell them. We can change our minds, make improvements, and respond to changing circumstances. We just then tell them again. And if we’re very lucky, they’ll give us suggestions about what they’d like to pay for. It becomes a conversation between members of a community that all want the business to succeed.

I still don’t think we should yell at developers, but we should look at sites that ask for our participation and try to see how they make money. If we can’t tell, we should ask. And if there’s still no good answer, then we should assume that’s because there isn’t one, and decide to participate with caution. Some websites may be compelling enough to warrant participation anyway (Twitter), but then at least we go in with open eyes.

So, to sum-up:

People: You are not the product. You’re a smart person making an educated decision about which companies you trust with your time, attention, and contributions. If you don’t know, or don’t trust, the business model of a company, don’t use their product.

Companies: Communicate with your users. Tell them how you’ll make money, early and often. Your honesty will help you earn their trust, and their trust is your most valuable asset.

In Business, Internet, Journalism on

18 December 2012

“If you’re not paying for the product, you are the product.”

I don’t know who said it first, but the line has achieved a kind of supernatural resonance online. And for good reason – it describes a kind of modern internet company that provides a free service. These businesses are designed to aggregate a large number of users in order to sell that audience’s aggregate attention, usually in the form of advertising.

But the more the line is repeated, the more it gets on my nerves. It has a stoner-like quality to it (“Have you ever looked at your hands? I mean really looked at your hands?”). It reminds me of McLuhan’s “the medium is the message,” a phrase that is seemingly deep but collapses into pointlessness the moment you think about using it in any practical way.

There are several subtextual assumptions present in “you are the product” I think are dangerous or just plain wrong that I’m going to attempt to tease out here. Many of these thoughts have been triggered by Instagram’s recent cluelessness, but they’re not limited to that. I also want to be clear that I’m not arguing that everything should be free or that we shouldn’t examine the business plans of the services we consume. Mostly I’m just trying to bring some scrutiny to this over-used truism.

Assumption: This is new or unique to the internet.

Free, ad-supported media has been around for a long, long time. When I was in college, before the web existed, I worked on alternative newspapers. Not only were they free, we actually walked around campus thrusting them in people’s faces.

I guess you could call the people we gave them to “the product,” but it sure didn’t feel that way when I was driving my VW Bug over Highway 17 filled to the roof with newsprint. The product was the thing I broke my back creating and hauling around.

Online ad-supported media is no different. It’s free, it builds an audience, and then it sells access to that audience in small chunks to companies willing to pay. There are ways to do that while still maintaining respect for the consumers. We’ve been doing it for years.

Assumption: Not paying means not complaining.

The “you are the product” line is most often repeated when a company that provides a free service does something that people don’t like. See Instagram’s recent terms change or any Facebook design update. The subtext is, this company does not serve you, you don’t pay for it, so shut up already.

But that’s crazy talk. If a company shows that they’re not treating you or your work with respect, vote with your feet. Uninstall. Delete account. Walk! And make sure they know why you split. It’s the only way we have to make companies feel the repercussions of dumb, user-hostile decisions.

Assumption: You’re either the product or the customer.

I’ve worked for, and even run, many companies in the last 20 years with various business models. Some provided something free in an attempt to build an audience large enough to sell advertising, some charged customers directly, and some did a combination of both. All treated their users with varying levels of respect. There was no correlation between how much money users paid and how well they were treated.

For example, at JPG Magazine we sold something to our audience (magazines, subscriptions, and ultimately other digital services) and we also sold ads and sponsorships (online and in print). We made it 100% clear to our members that their photos always belonged to them, and we had strict rules for what advertisers could do in the magazine. We also paid our members for the privilege of including their photos in the printed magazine (as opposed to Instagram’s new policy that they can use your photos however they want, even in ads, without paying you a dime).

This example is much more complicated than the black and white “you’re the product” logic allows. In some cases, users got the service for free. In others, they paid us to get the magazine. In still others, we paid them! So who/what is the product?

And just because you pay doesn’t mean you’re not the product. Cable TV companies take our money and sell us to the channels, magazines take our money and still sell ads, banks and credit cards charge us money for the service of having our money. Any store that has a “loyalty card” takes our money for products but gives us a discount in exchange for the ability to monitor what we buy. In the real world, we routinely become “the product” even when we’re already paying.

Assumption: Companies you pay treat you better.

I should be able to answer this with one word: AT&T. Or: Comcast. Or: Wells Fargo. Or: the government.

We all routinely pay companies that treat us like shit. In fact, I’d argue that, in general, online companies that I do not pay have far better customer policies and support than the companies I do pay.

The other day I had a problem with my Tumblr account. I sent an email. In less than an hour I had a kind, thorough, helpful response from a member of their support team. Issue fixed.

The next day I had a problem with my internet connection. I called my provider. After listening to hold music for a long while, I got someone on the phone who obviously spoke English as a second language, was not allowed to deviate from their script, and had less experience with the product than I did. They did not fix the problem. I was told to wait until it fixed itself.

The difference between Tumblr and my ISP? I pay my ISP over $50 a month. I pay Tumblr nothing.

Thinking critically about the business models of the services you use is a good thing. But assuming that because you pay means that things will be better is a very bad idea.

Assumption: So startups should all charge their users.

The apex of this argument is Maciej Ceglowski’s Don’t be a free user essay, in which he advocates that people “yell at the developers” of sites that don’t charge money.

Look, I’m thrilled that Pinboard has been a financial success for Maciej. I’m a paying member! And he’s right that it’d be nice if more companies could turn their users into customers that support the business.

But not all businesses can be run that way. Entertainment and media companies are rarely able to charge their consumers for their product. My company, Cute-Fight is a fun game, but I couldn’t throw up a brick wall on the homepage and expect it to succeed as Pinboard does. It’s just not that kind of business.

This blind “my way is the only right way” thinking is a poison to innovation and destructive to those of us building free services that do have business plans. Some businesses require mass adoption to work because they depend on economies of scale or a large audience. There is nothing inherently wrong with that.

What’s inherently wrong is a company changing its terms of service to screw their users. What’s wrong is a company that sells your data without your consent. What’s wrong is a company that scales back customer service to save a buck, leaving its customers angry and frustrated.

But those things usually have nothing to do with whether you’re paying them or not. They have to do with the company’s leadership, their level of complacency, and their demonstrated respect for their customers.

Bottom line it, Derek.

We can and should support the companies we love with our money. Companies can and should have balanced streams of income so that they’re not solely dependent on just one. We all should consider the business models of the companies we trust with our data.

But we should not assume that, just because we pay a company they’ll treat us better, or that if we’re not paying that the company is allowed to treat us like shit. Reality is just more complicated than that. What matters is how companies demonstrate their respect for their customers. We should hold their feet to the fire when they demonstrate a lack of respect.

And we should all stop saying, “if you’re not paying for the product, you are the product,” because it doesn’t really mean anything, it excuses the behavior of bad companies, and it makes you sound kind of like a stoner looking at their hand for the first time.

+

Update: Unsurprisingly, Instagram has said they’re going to “modify specific parts of the terms” in response to the outcry. We’ll see if they make substantive changes.

Followup: Instead of telling people “you are the product,” which creates a feeling of inevitability and powerlessness, let’s say this: “If you don’t know how a startup will make money, neither do they.”

In Cute-Fight on

6 December 2012

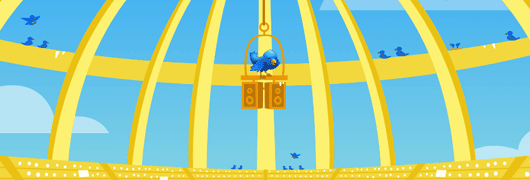

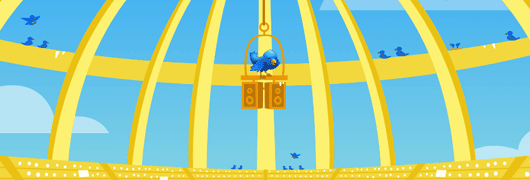

We’re thrilled to announce Cute-Fight’s newest venue, the ultimate cage match, the Twitterrific Thunderdome!

Gilded in gold and floating through the clouds is the Twitterrific Thunderdome, where animals of all kinds do battle over the finest periodicals.

The Thunderdome is sponsored by Twitterrific 5, a simply beautiful way to tweet for the iPhone & iPad. Color-coded timelines and customizable themes make reading fun and easy. Pictures, locations, and people search means tweeting is sweeter than ever. In the App Store now!

We want to thank the folks at Twitterrific for sponsoring this new venue. Twitterrific was the first app we ever used to tweet, and version 5 is better than ever. Plus, their mascot, Ollie, is an adorable bluebird! It was meant to be. Support Cute-Fight by giving the app a try. We think you’ll love it.

And then come start a fight in the new venue! We’ll see you there.

Other Newness

We’ve spruced up many of the pages in Cute-Fight, so take a look around if you haven’t visited recently. We’re especially proud of the cool new fighter leaderboards. Is your fighter there? Keep fighting and they will be!

And we’re always adding new badges and trophies. This week we added badge number 42, so it was obvious it had to have a towel on it. If you don’t get the reference, don’t panic.

And we’re always adding new badges and trophies. This week we added badge number 42, so it was obvious it had to have a towel on it. If you don’t get the reference, don’t panic.

We’ve also improved the code behind the scenes to play nicely with a wider variety of browsers. So if you had a problem with the site before, please give it another try.

See you in the fight!

About a year ago, when I

About a year ago, when I