Thirteen Ways of Not Looking at a Blackbird

By Gordon B. White

I.

I am a baby boy. In the bathtub, looking out, past my mother as she cries and holds the already wet washcloth to her eyes. Over her mouth. I am looking into the full-length mirror on the bathroom door.

I see no one.

I do not see my father.

A severed hand floats in the air. Drops of blood fall to the floor, splattering out on both sides of the border between the linoleum and carpet.

No one says, “I’ve sinned again,” as my mother cries.

II.

Our house is the one that looks perfect from the sidewalk. The siding is new, the eaves and trim are painted and bright. Gutters clean; lawn thick and green; picket fence as straight and white as teeth. The dogwoods bloom like big, pink brains in the spring, and lavender and bee balm fill the yard with their scent in summer.

Inside, we have a door in the kitchen that doesn’t lead anywhere. It has three silver locks—three like the bears in the story. A papa, a mama, and a baby, just like us.

At night, after she’s finished reading me fairytales and has turned off my light, I lie in bed and listen to the family of locks in the door to nowhere tumbling open and then back into place. The house shakes as heavy footsteps don’t go downstairs. Sometimes, too, I can almost hear other sounds that drift up through the ducts as if the house is singing sadly.

I ask Mama about it. I get her to hold her breath and put her ear to the vents.

She tells me that I can’t hear anything. That there’s nothing there. After that, I don’t hear it anymore.

III.

Because Daddy works until all hours, Mama is the one who tells me how the world works. Even though she didn’t get to go to school, her parents’ house was filled with towers of books and old papers that seem to grow from the piles of trash on the floor. She tells me that everything she knows, she knows from reading. I don’t realize it until later, but she’s closer to my age than Daddy’s.

I can ask her almost anything. How the flowers grow, how the TV works, why is the sky blue?

“Did you know,” she tells me, “that hundreds of years ago, back in olden times, people didn’t have a word for ‘blue’?”

I shake my head.

“And without a word for it, they couldn’t see it. Not like we can. I mean, it was there, right? But it wasn’t something they could make sense of.”

I can ask her almost anything, but only almost.

The sting of her hand is like a hornet and the red shape of it burns through my cheek. “You don’t ask about what he does,” she says. “You don’t see nothing, you don’t say nothing. Never. Never ever. You understand?”

Too stunned to cry, I nod.

“Good,” she says. “Good boys keep their mouths shut about business that ain’t theirs. They don’t talk about it and they don’t think about it.” She shakes her head. “Bad boys go to hell.”

IV.

I am in the kitchen and it is dark. The clock radio says 12:47 in red numbers that glare like eyes from the counter. I waited until the light beneath Mama’s door was off before sneaking down the hallway, each step seeming to find a new groaning board beneath the carpet, but I am now barefoot on the linoleum. I search the cabinets, trying not to make alarms of the pans and glass baking dishes as I search for the marshmallow cereal I know Mama has hidden. I’m only allowed one bowl on Saturdays, but I want to feel the chalky sugar on my tongue.

From behind the door to nowhere, I hear a crash. A thin gleam seeps from under the base of the heavy door, and there is a pounding that grows and grows behind it, as if rising from the empty ground beneath. The silver locks in the door tremble and shake, falling out of place.

The door to nowhere opens.

A naked woman with hair in a matted fury stands there. Blood drips from her fingers and mouth, black in the clock radio’s red glow, but she stands illuminated from behind by the light from a place that doesn’t exist. She sees me and her eyes widen; her mouth splits as if to laugh.

“Door?” she asks.

I point off down the front hall. She runs, bare feet smacking against linoleum, then wood.

But now there is a howling. A storm rising from nowhere. As it bursts into the kitchen, I don’t recognize the center at first, with its face marred by four ragged furrows. My eyes sink into those finger-deep trenches and I fall back as the maelstrom rages—screaming, shouting, smashing.

By now my mother is here, too, and when she says his name, I realize the storm is my father. The angry face coalesces back into the one I know, as it does, the thunderhead and ferocious gale which shook the kitchen dissolve into a fog.

I run back down the hall to my darkened bedroom. I am wrapped in a blanket and staring out the window for that naked woman, wondering if she’s cold, when the red and blue sirens descend.

V.

The law doesn’t know what to make of Mama. A dozen people think real hard about what she didn’t do and didn’t not do with no one, then throw up their hands. The man in the black robe says she can go but God help her. He shakes his head, says God help us all.

I can go too, because I’m so young, but part of it is that I have to talk with a lady once a week for what seems like forever.

Mama tells me it’s not a lie to say you don’t remember if you really don’t, so if I forget I won’t be a bad boy or liar. Good boys don’t talk about their fathers and mothers to strangers. Good boys don’t say what they did or didn’t see.

Good boys don’t say yes or no. They just say that they don’t know, sorry.

VI.

We change our names from nothing to something. I was so small that even the internet doesn’t know who I was when I wasn’t. And we have to leave the house, of course, but we make a go of it. Mama works, I go to school, and we come right back afterwards to wherever we happen to be that week.

Sometimes, though, when I look in the mirror or in the empty TV screen or the window at night, I see a face I don’t recognize. Or more precisely, I don’t. I ask Mama about it, but she says nevermind. It’s nothing.

It isn’t that we never talk about it. In fact, Mama talks everything over with me again and again until I remember clearly the empty wheelbarrows being pushed out of the basement I didn’t know we had. Until I remember garbage bags with nothing in them, carried out from the freezers by men in masks and white paper suits.

My memory of the old house is a field of yellow caution tape around empty holes between bushes of lavender and bee balm that nobody dug, men and women kneeling beside them and covering their faces with their hands in front of nothing at all.

VII.

My daddy is still alive. I ask about him sometimes, where he is, but the sting of Mama’s hand is a reminder I don’t often need. She’ll never take me to see him, she says, because while she’ll always love him, we need to move on.

We stay with her parents for a while—Gammy and Pawpaw—but they look at us like strangers. I hear them lock their bedroom door at night and Gammy would rather sit on the porch until Pawpaw gets home in the evening than be inside when just Mama and I are there.

“But you must have known?” Gammy says one night at dinner.

“I didn’t see anything,” Mama says.

“You must have guessed,” Pawpaw says. “I mean, so many—“

“I didn’t see nothing!” Mama slaps her hand against the table, rattling the silver. She stands but doesn’t leave. “I told them all, there was nothing to see.”

Pawpaw looks at me, squints. “What about you?”

I look at Mama and she glares at me hard enough across the table that my cheek begins to blister in the shape of her palm.

“No,” I say. “Nothing.”

“Not even that night? The one that got away?”

I don’t even need to look at Mama. I just shake my head and look at the chicken on my plate. Pawpaw spits on the floor by his boots.

“Disgusting,” he says.

VIII.

I look in the mirror and try to make sense of what I see, but I don’t have a word for who or what that is. The context is missing. The parts are all there—eyes, nose, lips, ears. They hover in an arrangement that should be recognizable, but the parts just don’t connect. I feel like a Mr. Potato Head without the potato.

In one of Pawpaw’s towers of paper I find an old library book on muscles and bones. The cover is like nothing I’ve seen before, a woman’s face and neck and shoulder leaning over as if asleep, while the secret world of roads and rivers beneath the skin is opened up. It makes me feel heat and shame, but it comes to live beneath my bed. At night, I push against and peel back myself where I can, trying to figure out what I am made of, inside and out.

Back in the mirror, I grow obsessed with the connective bits and parts in-between, learning new terms for the parts of the strange face I see: glabella; infraorbital furrow; infraorbital triangle; nasolabial furrow; philtrum; chin boss. In the fairytales Mama used to read me, having the true names always seemed to be a kind of magic and, for a few moments as I point and name them in the mirror, I think that I can almost see how I fit together.

But no. The longer I look, the more I realize the pieces are there, but something inside is missing.

I say my name over and over as I stare my reflection in the eye, as if catching the goblin in darkness and calling out “Rumplestiltskin!” might bind him. But that’s not my name—it’s not either of them.

I try to picture what it is inside of me, but I have nothing. So many memories of nothing and the things that no one did.

IX.

I dream I am back in our old house. I am in the kitchen, sitting at the table in front of a bowl of marshmallow cereal but I can’t find my hands to lift the spoon. As I’m sitting there, though, nothing begins to move around.

The front door slams, but when I peer out, the hall is empty. The heavy clomp of approaching boots shakes the walls and I want to cover my ears with the hands I can’t find, but as the footsteps stamp around me in circles, I can see nothing.

Frozen, I watch the refrigerator door open. A red and white can floats from inside, hisses as the tab is pulled, then pours out into thin air only to vanish. The cabinets swing open and closed; the faucet off and on; the knife drawer in and out. Then the crash of footsteps stops right beside me.

Over the years with the lady from the court, I have become accustomed to the sensation of being held down and pinned open as if for examination, and that familiar weight comes to rest on me in the dream, even though no one is looking at me. The needles of it burn like Mama’s slaps, but deeper and redder, piercing outward from somewhere within. Then nothing ruffles my hair like a faithful dog and shuffles over toward the door to nowhere. The three locks obediently twist themselves over one by one. The door swings open on its own.

A sudden crash of thunder and the kitchen is dark, as if the power went out. The only light comes from the doorway to nowhere. Another crash, but this time she is there.

All I can see now is that woman who came up from nowhere. She is standing there, naked and angry, bleeding as if born back from the nothing below, and my heart begins to race. There is something in me that is responding in a way I don’t have words to describe—a wash of heat and shame and desire and anger all at once.

I wake up and the sheets are a mess.

The look of repulsion on Mama’s face when she does the laundry in the morning says everything.

I still have the book on anatomy I stole from Pawpaw and I laboriously study all the terms to try and understand the woman. All the folds of muscle; the deposits of fat and flaps of skin; a tree of bone decorated like Christmas in tinsel of nerves and veins. Naming the parts helps me feel steadier, more in control. At least while I’m awake.

But I have the messy dreams again. Again. In a fit of shame, I cut the sheets into little pieces and throw them away, only to get caught a few days later stealing a replacement set from K-Mart. They call Mama to come take me home, but she won’t even speak to me.

X.

I want to tell someone, but I can’t. I open my mouth real wide sometimes when I’m in bed or when I’m at my new school or even when I’m in the bathroom. I just open it and try to make a sound that would maybe trick the words into coming out, but it just curdles into the most sickening groan.

The lady I’m made to talk to asks me what I remember. I tell her nothing. She asks me what I dream about. I tell her nothing. What do I want to tell her? About the nothing, nothing, nothing, but she only smiles and checks something off on a piece of paper.

We meet less and less as the years go by, until by the time eighth grade is done, the lady says I’m doing just fine. She says we don’t need to talk about it anymore.

XI.

I can feel my body changing. My brain too, squashed and pulled as the plates of my cranium shift. I am still having those dreams, and when I go to school or the store or the park, I can’t help but see that woman. Hiding behind trees. Down the bread aisle. Again and again—naked, bleeding, about to laugh.

I find out Daddy is dead more than a month after it happened when I hear some kids at school talking about it. At first it doesn’t register because the name they use wasn’t his real name. Butcher. Strangler. Ripper.

The words they use don’t reconcile with what I didn’t see.

But as they keep talking, one of them says his name—the one I used to share with him before Mama and I changed it—and for a moment I’m a baby boy again. I am in the house where we don’t speak of things Daddy doesn’t do.

But there’s a hole there in the house. A swirl of shadows that moves in and out of doors, through the halls, around me in the kitchen. A blank spot the size and approximate shape of my father, but one that bends light around until it slips by unnoticed. Did Mama and I talk so much around it that I became blind?

Well, the other kids are talking about it now. Saying the police had to dig up the backyard. They start listing out the pieces that were found and the ones that weren’t. They’re describing the tools. The basement behind the door with the three silver locks.

I can almost see through that haze in my memory of the house. I can almost …

The others say that one night, one of the girls fought back. She got away. Unlocked the door.

And like a flash of lightning, there she is standing among them. Proud and naked and my father’s blood on her hand and in her mouth. That same surge of desires and distress washes over me, making me hot and dizzy, but now I see clearly. I see that she’s the one who took it all away from us. She’s the one who talked. Who is talking now. Who—

When the teachers finally pull me off the other students, they drag me to the principal’s office, but first we stop at the boys’ restroom and they tell me to wash my face.

I splash it and feel a sting, but looking into the mirror I see nothing. There is nothing on my face or behind my eyes. I hear whispers from no one behind.

The principal is yelling at me, demanding to know just who I think I am. What are my parents going to say?

I can only laugh.

Nothing. I’m no one’s son.

XII.

“Mama,” I say, “I need to talk to you.”

There’s a hole I have to fill. A gap in my understanding.

“I need to talk about Daddy.”

“No,” she says.

“Please? I don’t know if what’s wrong with me is like what—“

A crash like thunder.

“Nothing was wrong with him. Nothing is wrong with you, too.”

XIII.

I may as well be a baby boy. In the shower, looking out through steamy glass, past the hooks where white towels hang like the damp skins of childhood ghosts. The side of my face burns, hot and red in the shape of a hand across my cheek. I am looking into the full length mirror on the bathroom door.

I see no one.

I do not see myself.

A severed hand floats in the air. Drops of blood fall to the tile floor, splattering out across my toes and mixing with the water as it swirls down the drain.

No one says, “I’ve sinned again,” as no one cries.

Monstrous Futures, edited by Alex Woodroe

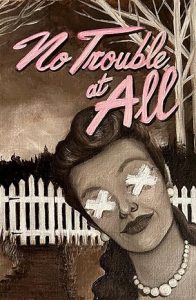

Monstrous Futures, edited by Alex Woodroe No Trouble at All, edited by Alexis Dubon and Eric Raglin

No Trouble at All, edited by Alexis Dubon and Eric Raglin Collage Macabre: An Exhibition of Art Horror, edited by Future Dead Collective

Collage Macabre: An Exhibition of Art Horror, edited by Future Dead Collective The Nameless Songs of Zadok Allen & Other Things that Should Not Be, edited by Jessica Augustsson

The Nameless Songs of Zadok Allen & Other Things that Should Not Be, edited by Jessica Augustsson Howls from the Wreckage: An Anthology of Disaster Horror, edited by Christopher O’Halloran

Howls from the Wreckage: An Anthology of Disaster Horror, edited by Christopher O’Halloran No One Will Come Back for Us and Other Stories, by Premee Mohamed

No One Will Come Back for Us and Other Stories, by Premee Mohamed Who Lost, I Found, by Eden Royce

Who Lost, I Found, by Eden Royce Skin Thief, by Suzan Palumbo

Skin Thief, by Suzan Palumbo The Inconsolables, by Michael Wehunt

The Inconsolables, by Michael Wehunt A Meeting in the Devil’s House a collection by Richard Dansky

A Meeting in the Devil’s House a collection by Richard Dansky The Best of Our Past, The Worst of Our Future, by Christi Nogle

The Best of Our Past, The Worst of Our Future, by Christi Nogle Cold, Black & Infinite: Stories of the Horrific & Strange, by Todd Keisling

Cold, Black & Infinite: Stories of the Horrific & Strange, by Todd Keisling Gordon B. White is Creating Haunting Weird Horror(s)

Gordon B. White is Creating Haunting Weird Horror(s) Have You Seen the Moon Tonight? and Other Rumors, by Jonathan Louis Duckworth

Have You Seen the Moon Tonight? and Other Rumors, by Jonathan Louis Duckworth