Darren Aronofsky

Darren Aronofsky is a filmmaker whose name many film lovers have become familiar with it over the years because of his work on the darkly hypnotic Black Swan (2010), the puzzling piece that’s The Fountain (2006) and the nightmarish Requiem For A Dream (2000). Yet it wasn’t with either of those I first discovered his work.

It was during my first year at university whilst studying Philosophy that one of my lecturers suggested I look for a film called Pi. I’d never heard of it before, but given my interested in signs and symbols and what they can tell us about the past, present and future; my lecturer thought I’d find the film fascinating a study that combines religion and mathematics. He was right, and I had no problem locating it at the university’s library that very evening.

Pi, dir. Darren Aronofsky, 1998

Pi, dir. Darren Aronofsky, 1998In the film we meet Max Cohen (Sean Gullette), a man with a brilliant mind when it comes to numbers. Max believes that everything in nature can be understood through them and this is an idea he lays out for us in the first few minutes of the film. Employing the use of SnorriCam, Aronofsky shoots Gullette walking through the busy streets of New York as Max, restates his assumptions for us.

Two. Everything around us can be understood and represented through numbers.

Three. If you graph the numbers of any system, patterns emerge.

Therefore, there are patterns everywhere in nature.”

Over the course of the film we learn that Max has been working on finding stock market patterns with home-built super-computer Euclid which then crashes after printing out a random 216-digit number. Eventually he realises he’s stumbled onto something big and it’s not long before a group of Hasidic Jews, along with guys from a Wall Street firm, want the numbers. While one group believes it to be the true name of God, the other believes it to be the key to wealth beyond their wildest dreams and each will do anything to get it.

The film ultimately asks if there could be a mathematical equation that simplifies the universe and everything in and outside of it with a sequence of numbers. It weaves together a plot which at first seems mighty complicated, gritty and claustrophobic but there are times when it also reminds me of Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis and comparisons have been made with David Lynch’s Eraserhead (1977) and David Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1983), but Aronofsky hints at another influence during his writing.

I was enthralled from start to finish. Pi not only left my imagination soaring to heights I’d never encountered before in an attempt to fully grasp all of Aronofsky’s ideas, but I was eager to find what else this incredible filmmaker had been responsible for in the realm of films.

Requiem For A Dream, dir. Darren Aronofsky, 2000

Requiem For A Dream, dir. Darren Aronofsky, 2000I didn’t have to look too far. A couple of years after Pi he wrote and directed Requiem For A Dream, based on Hubert Selby Jnr novel. Set in Coney Island, New York, it’s a nightmarish journey into the lives of four people; Harry (Jared Leto), his mother Sara Goldfarb (Ellen Burstyn), his girlfriend Marion (Jennifer Connelly) and his best friend Tyrone (Marlon Wayans). The film tells of their spiralling addictions as they all try to reach an increasingly unattainable reality. The American Dream.

We watch helplessly as Sara becomes addicted to weight-loss amphetamine pills and sedatives as she grows anxiousness about appearing on a television game show. Harry and Tyrone decide to sell drugs in the hope of making enough money to open a store to sell clothes that Marion designs but it spirals out of control landing one in prison and the other in hospital. Meanwhile Marion is drawn into performing in sex shows to fund her escalating addiction.

With its mix of close-ups and time-lapse photography, Requiem also employs the use of fast cutting (sometimes referred to hip-hop montage) to hone in on a style that fits the narrative structure of the film perfectly. The camera stays on the characters long enough to allow us to care for them deeply and to be affected by what’s unfolding around them, but it also moves quickly to let us experience their loss of control and anguish too.

After watching Requiem I found it hard to sleep. The images and sounds remained burned in my mind and when I did finally drift off, it was only to see them again in my dreams. Requiem, a masterpiece in filmmaking, was also a nightmarish vision that was impossible to forget, but it had a deeper message too.In Postmodern Hollywood, M. Keith Booker, a PhD professor at University of Florida, points out a very interesting contrast between Requiem and Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers (1994) and the film’s connection to mainstream capitalist behaviour:

As we watched the characters in the film fail in their attempts to make their dreams reality what we’re also witnessing is a story about anti-capitalism, a theme which is sometimes overlooked by general audiences who solely view it as an anti-drug movie. It presents us with a message that better living cannot be attained through increased consumption, whether it’s material items, food, drink, sex or drugs. The current state of first world countries is nothing more than a direct result of the illusion that increased consumption fills that void we all feel.

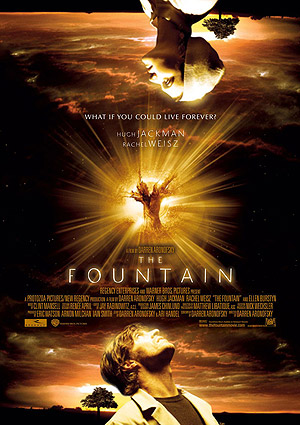

The Fountain, dir. Darren Aronofsky, 2006

The Fountain, dir. Darren Aronofsky, 2006As complex as Requiem was, Aronofsky’s next film, released in 2006, would prove to be his most misunderstood. The Fountain, starring Hugh Jackman and Rachel Weisz, brought together three stories; one told from the time of the Conquistadors, the second in the present time and the third from the far future in deep space. Told with some of the most dazzling images I’ve seen committed to the screen since Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), it would become another of my instant favourites.

In the film we have Tomás, a conquistador who embarks on a quest for his queen, Isabella. His journey takes him to the ancient Mayan city where, after an ambush, he finds the mythical Tree of Life that has to power to heal the wounds from his fight. Isabella hopes the Tree will help bring an end to a battle for her throne and she promises to marry Tomás if he returns with it.

In present time we find that Tommy is a neuroscientist working to find a cure for degenerative brain diseases. His wife Izzi is suffering from a brain tumour and while he’s convinced he can cure her, she makes peace with what’s to come while also writing a story relating to the ancient Mayans. The story is left unfinished when Izzie dies and we move to the next chapter.

Deep in space, in travelling in an ecosphere, Tom is alone as he moves ever closer to the golden nebula of Xibalba. With him is a large tree and he spends his time talking to it, meditating and writing. He hears Izzie’s voice, urging him to “finish it”, meaning the story. The tree is withering though and to bring it back to life, they must reach the nebula.

Black Swan, dir. Darren Aronofsky, 2010

Black Swan, dir. Darren Aronofsky, 2010To unravel the mystery of The Fountain we have to realise the story exists only in the here and now with Tommy and Izzi as he fights to save her from the flaming sword of mortality – he’s the conquistador she’s been writing about. What remains of her when she dies spurs him on to “finish it” and fulfil her wish, which is what we see when he plants the seed at her grave.

In 2010, after much anticipation, I saw the film I consider to be the crowning piece in Aronofsky’s career so far, although it’s one he didn’t write.

Taking inspiration from Pyotr Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake, he takes us into the fractured world of Nina (Natalie Portman), a timid, shy and sexually repressed dancer in a New York City ballet company who’s just won the role of the Swan Queen in a new production of Pyotr Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake. As the role requires her to be both the White Swan and the Black Swan, Nina struggles to find that darker side of herself. She’s pushed by her director Thomas (Vincent Cassel), her mother Erica (Barbara Hershey) and a beautiful new rival, Lily (Mila Kunis) until she breaks in half, arriving at an inevitable, burning climax that had me gasping for breath.

At times Black Swan could be considered to be Lynch-like in its depiction of Nina’s fractured world, reminding us of Mulholland Dr. (2001). It’s a place where doppelgangers roam freely and you’re never quite sure which side of the mirror you’re on. There are moments when Nina tears at herself as the Black Swan struggles to break out; these scenes are compelling yet difficult to watch because of the harm she wreaks on her body.

Other scenes are mesmerizing for the raw sexuality and voyeurism they invite us to. The club scene which plays to the sounds of The Chemical Brothers, although a sharp contrast to Nina’s world, is a brilliant juxtaposition of colours and sounds. The score by Clint Mansell, a frequent collaborator with Aronofsky, takes Tchaikovsky’s music from Swan Lake to a new level. Speaking with him at the time of the film’s release, he told me how these ideas came together,

- [1] Gaffney, P (2010) The Force of the Virtual: Deleuze, Science, and Philosophy, University of Minnesota Press

- [2] Booker, M.K. Postmodern Hollywood: What’s New in Film and Why It Makes Us Feel So Strange (2007), Praeger

- [3] Exclusive Interview With Clint Mansell

Black Swan was far more amazing, beautiful, terrifying and intoxicating than I expected it be. Despite it being Lynchy in some respects, the story is told linear and without too many riddles. It also reminded me of Lars von Trier’s Dancer In The Dark (2000), yet it remains quintessentially Aronofsky

If there’s an underlining theme to be found in Aronofsky’s work then it has to be that his films tell us stories about people and their obsessions with perfection. With Pi, it’s the mathematician and his quest to unlock the secrets of the universe. In Requiem it’s a group of people who all want a better life. For The Fountain we have a neuroscientist who wants to find a cure for his wife. Last but not least, there’s Black Swan, about a ballet dancer who just wants to be perfect. Though each of these films vary in style and tone, Aronofsky’s mark remains stamped on them as films that are beautifully challenging and utterly absorbing – the marks of a great director.

Patrick Samuel

The founder of Static Mass Emporium and one of its Editors in Chief is an emerging artist with a philosophy degree, working primarily with pastels and graphite pencils, but he also enjoys experimenting with water colours, acrylics, glass and oil paints.

Being on the autistic spectrum with Asperger’s Syndrome, he is stimulated by bold, contrasting colours, intricate details, multiple textures, and varying shades of light and dark. Patrick's work extends to sound and video, and when not drawing or painting, he can be found working on projects he shares online with his followers.

Patrick returned to drawing and painting after a prolonged break in December 2016 as part of his daily art therapy, and is now making the transition to being a full-time artist. As a spokesperson for autism awareness, he also gives talks and presentations on the benefits of creative therapy.

Static Mass is where he lives his passion for film and writing about it. A fan of film classics, documentaries and science fiction, Patrick prefers films with an impeccable way of storytelling that reflect on the human condition.

© 2022 STATIC MASS EMPORIUM . All Rights Reserved. Powered by METATEMPUS | creative.timeless.personal. | DISCLAIMER, TERMS & CONDITIONS

HOME | ABOUT | CONTACT | TWITTER | GOOGLE+ | FACEBOOK | TUMBLR | YOUTUBE | RSS FEED

CINEMA REVIEWS | BLU-RAY & DVD | THE EMPORIUM | DOCUMENTARIES | WORLD CINEMA | CULT MOVIES | INDIAN CINEMA | EARLY CINEMA

MOVIE CLASSICS | DECONSTRUCTING CINEMA | SOUNDTRACKS | INTERVIEWS | THE DIRECTOR’S CHAIR | JAPANESE CINEMA