Andy Razaf, Maxine Sullivan: Mound Bayou

Andy Razaf, born December 16 1895, died February 3 1973.

Razaf was a song-writer, poet, African prince and associate of Fats Waller, who wrote many songs including Ain’t Misbehavin’, Honeysuckle Rose and Black And Blue.

According to Wikipedia: Razaf was born in Washington, D.C. His birth name was Andriamanantena Paul Razafinkarefo. He was the son of Henri Razafinkarefo, nephew of Queen Ranavalona III of Imerina kingdom in Madagascar, and Jennie (Waller) Razafinkarefo, the daughter of John L. Waller, the first African American consul to Imerina. The French invasion of Madagascar left his father dead, and forced his pregnant 15-year-old mother to escape to the United States, where he was born in 1895.

Singer Maxine Sullivan recorded a fine album of Razaf’s songs, with trumpeter Charlie Shavers amongst others, in 1956. She included one of Razaf’s lesser-known songs, Mound Bayou.

Again, accord to Wikipedia: Mound Bayou traces its origin to people from the community of Davis Bend, Mississippi. The latter was started in the 1820s by the planter Joseph E. Davis (brother of former Confederate president Jefferson Davis), who intended to create a model slave community on his plantation. Davis was influenced by the utopian ideas of Robert Owen. He encouraged self-leadership in the slave community, provided a higher standard of nutrition and health and dental care, and allowed slaves to become merchants. In the aftermath of the Civil War, Davis Bend became an autonomous free community when Davis sold his property to former slave Benjamin Montgomery, who had run a store and been a prominent leader at Davis Bend. The prolonged agricultural depression, falling cotton prices and white hostility in the region contributed to the economic failure of Davis Bend.

Isaiah T. Montgomery led the founding of Mound Bayou in 1887 in wilderness in northwest Mississippi. The bottomlands of the Delta were a relatively undeveloped frontier, and blacks had a chance to clear land and acquire ownership in such frontier areas. By 1900 two-thirds of the owners of land in the bottomlands were black farmers. With high debt and continuing agricultural problems, most of them lost their land and by 1920 were sharecroppers. As cotton prices fell, the town suffered a severe economic decline in the 1920s and 1930s.

Shortly after a fire destroyed much of the business district, Mound Bayou began to revive in 1942 after the opening of the Taborian Hospital by the International Order of Twelve Knights and Daughters of Tabor, a fraternal organization. For more than two decades, under its Chief Grand Mentor Perry M. Smith, the hospital provided low-cost health care to thousands of blacks in the Mississippi Delta. The chief surgeon was Dr. T.R.M. Howard who eventually became one of the wealthiest black men in the state. Howard owned a plantation of more than 1,000 acres (4.0 km2), a home-construction firm, a small zoo, and built the first swimming pool for blacks in Mississippi. In 1952, Medgar Evers moved to Mound Bayou to sell insurance for Howard’s Magnolia Mutual Life Insurance Company. Howard introduced Evers to civil rights activism through the Regional Council of Negro Leadership which organized a boycott against service stations which refused to provide restrooms for blacks. The RCNL’s annual rallies in Mound Bayou between 1952 and 1955 drew crowds of ten thousand or more. During the trial of Emmett Till‘s alleged killers, black reporters and witnesses stayed in Howard’s Mound Bayou home, and Howard gave them an armed escort to the courthouse in Sumner.

Author Michael Premo wrote:

Mound Bayou was an oasis in turbulent times. While the rest of Mississippi was violently segregated, inside the city there were no racial codes… At a time when blacks faced repercussions as severe as death for registering to vote, Mound Bayou residents were casting ballots in every election. The city has a proud history of credit unions, insurance companies, a hospital, five newspapers, and a variety of businesses owned, operated, and patronized by black residents. Mound Bayou is a crowning achievement in the struggle for self-determination and economic empowerment

The top quality of Mercer

Johnny Mercer was born in Savannah, Georgia on November 18 1909; he died in Los Angeles, 25 June 1976.

He was one of the Twentieth Century’s great song lyricists, and was also a fine singer himself. He recorded as a vocalist with Paul Whiteman, Wingy Manone, Benny Goodman and Jack Teagarden.

He duetted with Teagarden on what is surely the best jazz Christmas record of all time (not that there’s a lot of competition, Christmas Night In Harlem. For a Southern white guy, he was also remarkably enlightened and free of prejudice: he just loved music and couldn’t give a damn about skin pigmentation. When Nat Cole was having a hard time from racists, Mercer offered him personal support and publicly denounced the racists (though, it must be said, Cole was signed at that time to Mercer’s Capitol label, but I like to think he’d have done it anyway).

Above: Mercer on the Nat ‘King’ Cole TV show

Mercer’s most famous song is Moon River , written (with Henry Mancini) for the film Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Personally, I have to say I don’t find it a very engaging tune or lyric. But I’m glad it brought Johnny some wealth and security towards the end of his life.

I much prefer Blues In The Night, his 1941 masterpiece, written with Harold Arlen. Here’s the Benny Goodman version, with Peggy Lee on vocals. The rather strange falsetto scatting following Peggy’s vocal is by trombonist Lou McGarity (how do I know that? Am I a bit sad or what?); Benny himself, on clarinet, briefly returns to his wailing Chicagoan roots in the closing bars of the number:

September in the Rain, with Dinah Washington

There’s only one song for today (and, indeed, for this month), and only one singer:

Dinah Washington was one of the few black jazz/R&B singers to break into the mainstream US hit parade: in 1959, she had her first top ten pop hit, with a version of “What a Diff’rence a Day Made“,[11] which made Number 4 on the US pop chart. Her band at that time included arranger Belford Hendricks, with Kenny Burrell (guitar), Joe Zawinul (piano), and Panama Francis (drums). She followed it up with a version of Irving Gordon‘s “Unforgettable“, and then two highly successful duets in 1960 with Brook Benton, “Baby (You’ve Got What It Takes)” (No. 5 Pop, No. 1 R&B) and “A Rockin’ Good Way (To Mess Around and Fall in Love)” (No. 7 Pop, No. 1 R&B). Her last big hit was “September in the Rain” in 1961 (No. 23 Pop, No. 5 R&B).[10]

Early on the morning of December 14, 1963, Washington’s seventh husband, football great Dick “Night Train” Lane, went to sleep with his wife, and awoke later to find her slumped over and not responsive. Doctor B. C. Ross came to the scene to pronounce her dead.[7] An autopsy later showed a lethal combination of secobarbital and amobarbital, which contributed to her death at the age of 39. She is buried in the Burr Oak Cemetery in Alsip, Illinois (Wikipedia).

The lovely, gentle, sad but joyous jazz star: Lester Young

Above: Pres bursts into jazz immortality in 1936

Pres, or Prez (“The President of all Saxophone Players”, so named by Billie Holiday), died in New York on 15 March 1959. He was born in Woodville Mississippi on 27 August 1909, so perhaps that happier anniversary should be Lester Young Day.

“Lester was a dancer, a dreamer, a master of time and its secrets. Foremost among them: equilibrium. He never stumbles on the tightrope of swing, of tension and relaxation held in perfect ying-yang balance. He is a juggler, a high-wire artist without a net, a diver, a gambler, a gamboler.

“The discoveries, the clear profundities of late Lester have been little understood. Some of his languor, no doubt, was the result of the need for conservation of energy. But what he made of this necessity! He was indeed a mother of invention….

“Long live gentle Lester, who loved life despite what it had done to him, and who never stopped reaching out, gifts in hand. To hell with those who call your strength weakness because you turned the pain inward, upon yourself rather than others, and offer simplistic explanations for your singular fate. Perhaps they envy you your immortality” – Dan Morgenstern, in ‘A Lester Young Reader’, edited by Lewis Porter, pub: Smithsonian, 1991.

I’ve posted this clip of Lester’s final encounter with his platonic love, Billie Holiday, several times before. But there may still be people who haven’t seen it. Watch Billie’s face as Pres (the second soloist, following Ben Webster) struggles through his slightly strained, but beautifully-constructed solo: it’s pure love in its most refined and intense manifestation; a couple of years after this 1957 TV show (on which Lester was not booked to appear, but turned up nevertheless) both Billie and Lester would be dead:

Kay Starr: a true Star(r) right to the end

Katherine Laverne Starks (aka Kay Starr) July 21 1922 – Nov 3, 2016

One of my favourite singers, Kay Starr, died last November almost unnoticed, despite the fact that she’d had some big hits (Wheel Of Fortune, Rock And Roll Waltz, etc) in the 50’s.

Kay came up in the late thirties and sang with the big bands of Joe Venuti, Bob Crosby, Glenn Miller and Charlie Barnett, but was equally at home with hillbilly music, small group jazz and the blues. Legend has it that Billie Holiday said Kay (whose dad was Native American and mum Irish) was the only “white gal” who could really sing the blues.

I meant to write something at the time of her death, but somehow didn’t get round to it. However, this month’s Just Jazz magazine carries a delightful reminiscence by US bandleader Jim Beatty that deserves a wider readership. It’s not altogether politically correct, but exudes affection, respect and a little bit of sadness.

Remembering Kay Starr

By Jim Beatty

When I was a young guy in high school Kay Starr was one of the most popular singers on the United States pop charts. But she covered all the bases and sang all styles from Country, Swing, to jazz. Not only that, she was cute and good looking — the kind of girl that my friends and I would love to have a date with.

She was born in Dougherty, Oklahoma in 1922, her father was a full blown Iroquois Indian and her mother was Irish. Kay’s family did not make a lot of money, but raised chickens at home and every day when Kay got out of school she came home and sang to the chickens. Her parents entered her into a talent contest: she won, and that led to a 15-minute record show at three dollars a show. They later moved to Memphis, Tennessee, and she went into radio there as well. Jazz violinist Joe Venuti was passing through town with his band and listened to her sing on the radio and offered her a job. She was only 15 years old and still in school, but she sang with Joe and his band in the summertime when school was out. Joe Venuti was very protective of her and on top of that her mother came with her to all her jobs. She was with the Glenn Miller Orchestra for two months before going with Charlie Barnett and his band in 1945. She later went on her own as a featured singer and in 1956 recorded the number one hit in the United States and UK – The Rock And Roll Waltz. Kay followed that with more smash hits, such as Side By Side and Wheel Of Fortune.

David Christopher had booked Kay into his Lyons English Grille showroom on Memorial Day weekend 2010, and asked me if I’d like to play the show. Of course I was there with bells on. I met Kay in the musicians’ room so we could all run over the show together. She was wonderful to talk to and surprised that I knew so much about her early life singing jazz with Joe Venuti. We had a packed house that night and Kay sang many of her favourites, along with a beautiful rendition of If You Love Me. That night turned out to be Kay Starr’s last public appearance.

Following the show, Katie (that’s what her friends called her), her assistant Ann, along with David Christopher and I, sat down and relaxed with some drinks. I noticed that my scotch and water was disappearing rapidly and I didn’t remember even having a sip. What was happening was Katie chugalugging her scotch and water and switching her glass with me when I wasn’t looking, putting her empty glass in front of me and taking my full one. We later heard from her assistant Ann, that Katie loved her scotch and you had to keep an eye on her at all times.

David Christopher and I went to a restaurant and got some cold sandwiches which we brought back to Katie’s hotel room. So there I was, sitting on a bed with Kay Starr, eating a sandwich and drinking a glass of white wine. My childhood dream came true and I was in bed with Kay Starr. The only trouble was that I was 76 years old and Kay was 88, plus we were accompanied by Kay’s assistant and David Christopher. Katie hadn’t lost her sense of humour and when we opened the sliding door onto the hotel patio to leave — she said, very loudly so everyone could hear — “Thanks for the business, boys!”

Below: Kay Starr with Les Paul in New York, five years before the final gig with Jim:

Billie Holiday: I’ll Be Seeing You

Any musical interlude, just at the moment, needs to be sad. This version of I’ll Be Seeing You, by Billie Holiday with Eddie Heywood’s Orchestra in 1944, is certainly that; Billie was a jazz improviser first and foremost, but she also respected the lyrics:

Remembering Ella

Ella Fitzgerald was born just over 100 years ago on 19 April 1917, and died on 15 June 1996. Mid-way between these two anniversaries seems like a good time to remember possibly the greatest of all jazz singers. Come to that, not just the greatest jazz singer: no one interpreted the ‘Great American Songbook’ as effectively as Ella; and no singer in any genre could equal her for sheer beauty of sound.

And yet Ella has had something of a bum deal in terms of reputation – particularly from jazz purists, who almost to a man (and I chose that expression carefully), will compare her unfavourably to her near-contemporary Billie Holiday. Billie (goes the Jazz Party Line) may have had a limited voice, but she exuded passion, sincerity, true jazz feeling and a natural affinity with the blues. Ella, on the other hand, (this is still the Party Line, you understand) was all vocal technique, but had little or no feeling, no blues sensibility and – if you want the bald truth – was scarcely a jazz singer at all!

All of which is not just unfair to Ella: it’s complete rubbish that owes more to ignorant mythology than it does to any serious musical appreciation. The idea that Billie was an authentic “jazz singer”, whose every note was suffused with passion, sincerity and suffering, is a nonsense that owes more to her ghosted (and highly unreliable) ‘autobiography’ Lady Sings the Blues (and the awful Diana Ross film based upon it), than to any boring old facts. In reality, Billie -given the opportunity- demanded lush strings and ‘commercial’ arrangements on her later recording sessions (on which her voice was often dire). And Ella could sing with sincerity and passion (try Ill Wind from her Harold Arlen album, or Do Nothing till You Hear from Me from her Ellington album – both on ‘Verve’), in addition to simply swinging like the clappers.

Jazz has always been very male. It was one of the first art forms to insist upon racial equality: how could it not, when all (excepting a few whites like Beiderbecke, Goodman and Teagarden) its leading practitioners were black Americans? But the fact remains that, for all its racial equality, jazz was always seriously sexist.

Women were allowed in jazz as vocalists, provided they were pretty. Mary Lou Williams was the exception and even she had the advantage of being “the Pretty Gal Who Swings the Band”; she played the piano better than most men, and also arranged for Andy Kirk’s band. Ella Fitzgerald, who could never have been called a “Pretty Gal” started singing in the 1930’s, copying the white New Orleanian Connie Boswell: Ella , nervous as she alwys would be, won a talent competition at the Apollo Ballroom , and wasn’t pretty – but had the most fabulous voice. Benny Carter heard her there and recommended her to bandleader Chick Webb. From then on her career took off, first with Chick Webb’s band (which she took over for two years when he died in 1939), and then as a soloist.

She adapted to bebop with ease; almost every record she made from the late 1940’s through to the mid 1950’s is a lesson in bop phrasing. She could also scat-sing with a facility and wit unmatched by anyone except Louis Armstrong or Leo Watson. Then, Norman Granz (of Verve records) came up with the “Song Book” idea: give Ella the task of recording all the significant songs of – say- Gershwin, Porter, or Mercer, and give her the lush backing of Nelson Riddle, or the brassy drive of Billy May, and you have a series of classics. No serious music lover (even if you’re not particularly into jazz) should be without them.

But Ella, despite her success, was never really happy. She wasn’t obviously unhappy the way Billie Holiday was (although Billie’s reputation as a tragic victim is at least in part the result of her own “successful exploitation of her (own) personal life” in the words of one commentator). Ella’s unhappiness was, apparently, that she simply felt unloved and felt unattractive to men. Sarah Vaughan – another wonderful vocalist – felt the same way. Ella was married to the bass player Ray Brown for a while in the 1950’s, but that didn’t work out (nor did a second marriage), possibly because of her inferiority complex. Her friend, Marian Logan, at the time of a 1950 European tour with Norman Granz’s ‘Jazz at the Philharmonic’ described her thus;

“She was shy and she was very insecure about her looks. She used to tell me, ‘You’re so beautiful’. It was hard on Ella. Everyone around her was so young and slim and she was young and fat, and she thought of herself, I guess, as kind of ordinary. Nobody ever made her realise that she had a beauty that was a lot different and a lot more lasting than the beauty of those ‘look pretty and the next day look like a raggedy-bose-of yacka-may’. Nobody ever made her feel valuable even for her talents. Nobody made much over her. She was always a very lonely person”.

The jazz world is -rightly- proud of its organic anti-racism; it has little to be proud of in its treatment of women. The reason for Ella’s underappreciation in jazz circles has, I suspect, a lot to do with her looks. She was – to put it bluntly – “matronly”(“homely” is another frequently used description) in a world where female singers were judged as much by their looks as by their voice. Billie Holiday was not exactly a conventional beauty, but even in her declining years she remained a striking, handsome woman. Ella just had that voice.

She ended up as the elder stateswoman of jazz: honoured and acknowledged by all, but lonely. Her performances never moved me in quite the the way Billie Holiday’s do. But she kept the “Great American Songbook” alive the way no-one else could. For that – if nothing else- she deserves to be remembered.

Yes, Ella had real beauty, and not just in her voice (although that was -quite simply- the most gorgeous vocal sound ever produced in jazz or anywhere else): she was a lovely, loving, modest and strangely child-like talent who never quite believed in her own ability. In fact, she seems to have seriously doubted herself throughout her career. Her life strikes me as more tragic than that of Billie Holiday, who may have made bad choices in men and in many other matters, but did so voluntarily (it has even been suggested that she -Billie- was a masochist). Ella was lonely, insecure and never realised how good and important she was. The sexism and superficiality of the jazz/showbiz world, and the wider society it existed within, was, in large part, to blame. But that voice…

(NB: Fortunately, Ella’s geatest recordings are widely and easily available: I recommend ‘The Best of the Song Books’, Verve 519 804-2 and ‘The Best of the Song Books: The Ballads’, Verve 521 867-2)

A musical interlude from Miss Lee Wiley

Just in case anyone wondered where I’ve been this week, here’s a favourite singer with a clue:

2016 on its death bed

As the old year of 2016 is now dying, here are some of my favourite pieces of writing about death.

This came to mind because of the very recent death of Richard Adams. The death scene which ends Watership Down – well, there must be a German word which describes knowing something is sentimental, yet still being moved by it. Disneyschmerz perhaps? The nature-loving agnostic imagines an afterlife with as false a comfort as angels escorting the departed to heaven yet a rabbit soul eternally scampering through the beech woods has great charm. By now the reader has come to like and respect Hazel and enjoy the rabbit’s eye view of the English countryside, in whose pockets between roads, housing and farms the rabbits make their lives.

One chilly, blustery morning in March, I cannot tell exactly how many springs later, Hazel was dozing and waking in his burrow. He had spent a good deal of time there lately, for he felt the cold and could not seem to smell or run so well as in days gone by. He had been dreaming in a confused way — something about rain and elder bloom ~ when he woke to realize that there was a rabbit lying quietly beside him — no doubt some young buck who had come to ask his advice. The sentry in the run outside should not really have let him in without asking first. Never mind, thought Hazel. He raised his head and said, “Do you want to talk to me?”

“Yes, that’s what I’ve come for,” replied the other. “You know me, don’t you?”

“Yes, of course,” said Hazel, hoping he would be able to remember his name in a moment. Then he saw that in the darkness of the burrow the stranger’s ears were shining with a faint silver light. “Yes, my lord,” he said, “Yes, I know you.”

“You’ve been feeling tired,” said the stranger, “but I can do something about that. I’ve come to ask whether you’d care to join my Owsla. We shall be glad to have you and you’ll enjoy it. If you’re ready, we might go along now.”

They went out past the young sentry, who paid the visitor no attention. The sun was shining and in spite of the cold there were a few bucks and does at silflay, keeping out of the wind as they nibbled the shoots of spring grass. It seemed to Hazel that he would not be needing his body any more, so he left it lying on the edge of the ditch, but stopped for a moment to watch his rabbits and to try to get used to the extraordinary feeling that strength and speed were flowing inexhaustibly out of him into their sleek young bodies and healthy senses.

“You needn’t worry about them,” said his companion. “They’ll be all right — and thousands like them. If you’ll come along, I’ll show you what I mean.”

He reached the top of the bank in a single, powerful leap. Hazel followed; and together they slipped away, running easily down through the wood, where the first primroses were beginning to bloom.

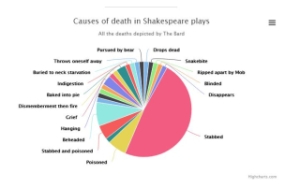

Shakespeare was much obsessed with deaths – 74 of them in his plays. Someone did a play which featured them all.

These death scenes though are mostly violent sword stabbings, with the occasional strangulation and poisoning so I’ll quote the death of Falstaff reported in Henry V.

ACT II SCENE III London. Before a tavern.

Enter PISTOL, Hostess, NYM, BARDOLPH, and BOYHOSTESS Prithee, honey-sweet husband, let me bring thee to Staines.

PISTOL No; for my manly heart doth yearn.

BARDOLPH Be blithe: Nym, rouse thy vaunting veins:

BOY Bristle thy courage up; for Falstaff he is dead,

And we must yearn therefore.

BARDOLPH Would I were with him, wheresome’er he is, either in heaven or in hell!

HOSTESS Nay, sure, he’s not in hell: he’s in Arthur’s bosom, if ever man went to Arthur’s bosom. A’ made a finer end and went away an it had been any christom child; a’ parted even just between twelve and one, even at the turning o’ the tide: for after I saw him fumble with the sheets and play withflowers and smile upon his fingers’ ends, I knew there was but one way; for his nose was as sharp as a pen, and a’ babbled of green fields. ‘How now, sir John!’ quoth I ‘what, man! be o’ good cheer.’ So a’ cried out ‘God, God, God!’ three or four times. Now I, to comfort him, bid him a’ should not think of God; I hoped there was no need to trouble himself with any such thoughts yet. So a’ bade me lay more clothes on his feet: I put my hand into the bed and felt them, and they were as cold as any stone; then I felt to his knees, and they were as cold as any stone, and so upward and upward, and all was as cold as any stone.

The Hostess would have been accustomed to tend the dying at a time when the women of the household did the nursing.

The Death of the Mrs Proudie from The Last Chronicle of Barset by Anthony Trollope

Trollope wrote 6 volumes about Cathedral politics in Barsetshire. One day in his club he overheard two men complaining that he was reintroducing the same old characters, including Mrs Proudie and how tired they were of it. So he told the men that he would kill her off that day.

Mrs Proudie of much reforming Evangelical energy has dominated her husband the bishop to carry out her will to the point of utterly humiliating him so they are now bitterly estranged.

Mrs. Proudie’s own maid, Mrs. Draper by name, came to him and said that she had knocked twice at Mrs. Proudie’s door and would knock again. Two minutes after that she returned, running into the room with her arms extended, and exclaiming, “Oh, heavens, sir; mistress is dead!” Mr. Thumble, hardly knowing what he was about, followed the woman into the bedroom, and there he found himself standing awestruck before the corpse of her who had so lately been the presiding spirit of the palace.

The body was still resting on its legs, leaning against the end of the side of the bed, while one of the arms was close clasped round the bed-post. The mouth was rigidly closed, but the eyes were open as though staring at him. Nevertheless there could be no doubt from the first glance that the woman was dead. ..

….The bishop when he had heard the tidings of his wife’s death walked back to his seat over the fire, ….. But there was no sound; not a word, nor a moan, nor a sob. It was as though he also were dead, but that a slight irregular movement of his fingers on the top of his bald head, told her [Mrs Draper] that his mind and body were still active. ..

She had in some ways, and at certain periods of his life, been very good to him. …..She had never been idle. She had never been fond of pleasure. She had neglected no acknowledged duty. He did not doubt that she was now on her way to heaven. He took his hands down from his head, and clasping them together, said a little prayer. It may be doubted whether he quite knew for what he was praying. The idea of praying for her soul, now that she was dead, would have scandalized him. He certainly was not praying for his own soul. I think he was praying that God might save him from being glad that his wife was dead.

(As a strict Protestant, Bishop Proudie would not pray for a soul whose destiny is decided at death.)

A Very Easy Death by Simone de Beauvoir

After a long agony of being treated for cancer, Simone de Beauvoir’s mother finally dies. Her sister, Poupette, is at the death bed. De Beauvoir was an atheist, her mother a devout Catholic.

Maman had almost lost consciousness. Suddenly she cried, “I can’t breathe!” her mouth opened, her eyes stared wide, huge in that wasted, ravaged face: with a spasm she entered into coma..

Poupette rang me up: I did not answer. The operator went on ringing for half an hour before I woke. Meanwhile Poupette went back to Maman; already she was no longer there – her heart was beating and she breathed, sitting there with glassy eyes that saw nothing. And then it was over. “The doctors said she would go out like a candle: it wasn’t like that, it wasn’t like that at all,” said my sister, sobbing.

But, Madame,” replied the nurse, “I assure you it was a very easy death.”

“Maman” though religious did not ask for a priest – de Beauvoir concludes:-

“She knew what she ought to have said to God – “Heal me. But Thy will be done: I acquiesce in death.” She did not acquiesce. In this moment of truth she did not choose to utter insincere words…

Maman loved loved life as I love it and in the face of death she had the same feeling of rebellion that I have. During her last days I received many letters with remarks on my most recent book: “If you had not lost your faith death would not terrify you so,” wrote the devout, with rancorous commiseration. Well-intentioned readers urged, “Disappearing is not of the least importance: your works will remain.” And inwardly I told them all that they were wrong. Religion could do no more for my mother than the hope of posthumous success could for me. Whether you think of it as heavenly or as earthly, if you love life immortality is no consolation for death.

A devout Christian, C S Lewis did take consolation in his wife’s immortality though the whole of A Grief Observed is about the despair and misery at his loss of faith he undergoes after her painful death (cancer again). He longs for her undeath but at the end thinks she has been transfigured into something resembling pure intelligence, away from her torturing body:-

How wicked it would be, if we could, to call the dead back! She said not to me but to the chaplain, “I am at peace with God.” She smiled, but not at me. Poi si torno all’ eterna fontana.

The last words in Italian being Dante’s view of his beloved Beatrice in a blissful afterlife.

Lewis’s view of death is harsher in Till We Have Faces, a surprisingly feminist work. Orual the heroine is about to enter into single combat with an enemy which will decide the fate of their city. Her father, the king and a cruel brute, has been lying helpless with a stroke. She is in the royal Bedchamber, searching out armour.

And it was when we were most busied that the Fox’s voice from behind said, “It’s finished.” We turned and looked. The thing on the bead which had been half-alive for so long was dead; had died (if he understood it) seeing a girl ransacking his armoury.

“Peace be upon him,” said Bardia. “We’ll be done here very shortly. Then the women can come to wash the body.” And we turned again at once to settle the matter of the hauberks.

And so the thing I had thought of for so many years at last slipped by in a huddle of business which was, at that moment, of more consequence. An hour later, when I looked back, it astonished me. Yet I have often noticed since how much less stir nearly everyone’s death makes than you expect. Men better loved and more worthy loving than my father go down making only a small eddy.

How the world shrugs off our death is brutally stated by A E Housman’s in Is My Team Ploughing:-

So to all, a long and healthy life, and then a quick and easy death, causing the least amount of nuisance and hassle.

Happy birthday, Fats!

Things have been a bit depressing for many of us lately, so let me bring a little bit of joy into your lives, courtesy Thomas ‘Fats’ Waller, who was born this day in New York, 1904.

Here is the “Harmful Little Armful” himself in the 1943 film Stormy Weather, also featuring drummer Zutty Singleton, bassist Slam Stewart, Benny Carter on trumpet, Lena Horne and dancer Bill ‘Bojangles’ Robinson.

Fats died shortly after this was filmed, but you’d never for a moment guess that from the sheer joie de vivre of this performance of his own most famous tune: