Prompted by Gillian and Adam’s – A Different North project, my thoughts turned once again to notions of the North, similar notions have been considered in my previous posts:

A Taste of the North and A Taste of Honey.

I recalled the 2016 season Sky Football promotional film, it had featured a street in Ashton under Lyne, it had featured Hamilton Street.

A street spanning the West End and the Ryecroft areas of the town, the town where I had lived for most of my teenage years. The town where my Mam was born and raised in nearby Hill Street, nearby West End Park where my Grandad I had worked, nearby Ashton Moss and Guide Bridge.

This is an area familiar to me, which became the convergent point of a variety of ideas and images, mediated in part by the mighty Murdoch Empire.

Here was the coming together of coal and cotton, an influx of population leaving the fields for pastures new.

In the film, Leytonstone London born David Beckham is seen running down the snow covered northern street.

A credit to our emergent mechanical snow generation industry.

According to snowmakers.com, it takes 74,600 gallons of water to cover a 200 by 200-foot plot with 6 inches of snow. Climate change is cutting snow seasons short, we make snow to compensate, more energy is spent making snow, more coal is burned, more CO2 is released.

It is to be noted that locally there has been a marked decline in snowfall in recent years, the Frozen North possibly a thing of the past.

The temperatures around the UK and Europe have actually got warmer over the last few decades, although when you are out de-icing your car it may not actually feel as though it has. Whilst this can not be directly link to climate change, it is fair to assume that climate change is playing a part.

It is also to be noted that Sky Supremo Rupert Murdoch has described himself as a climate change “sceptic”.

Appearing arms raised outside of the home of a family clustered around the television, in their front room.

Filming the ad was great and the finished piece is a really clever way of showing that you never know what might happen in football, I always enjoy working with Sky Sports and I’m proud to be associated with their football coverage.

The area does have a football heritage, Ashton National Football Club played in the Cheshire County League in the 1920s and 1930s. They were sometimes also known as Ashton National Gas, due to their connections with the National Gas and Oil Engine Company based in the town.

Illustrative of a time when sport and local industry went hand in glove.

The National Ground was subsequently taken over by Curzon Ashton who have since moved to the Tameside Stadium.

Ashton & Hyde Village Hotels occupy the front of shirt sponsors spot on our new blue and white home shirt, while Seed of Speed, our official conditioning partners, feature on the arm, and Minuteman Press occupy the back of the shirt. Meanwhile, Regional Steels UK Ltd. are the front of shirt sponsors on our new pink and black away kit.

Illustrative of a time when sport and local industry continue to work hand in glove.

Local lad Gordon Alexander Taylor OBE is a former professional footballer. He has been chief executive of the English footballers’ trades union, the Professional Footballers’ Association, since 1981. He is reputed to be the highest paid union official in the world.

His mobile phone messages were allegedly hacked by a private investigator employed by the News of the World newspaper. The Guardian reported that News International paid Taylor £700,000 in legal costs and damages in exchange for a confidentiality agreement barring him from speaking about the case.

News International is owned by our old pal Rupert Murdoch, the News of the World no longer exists.

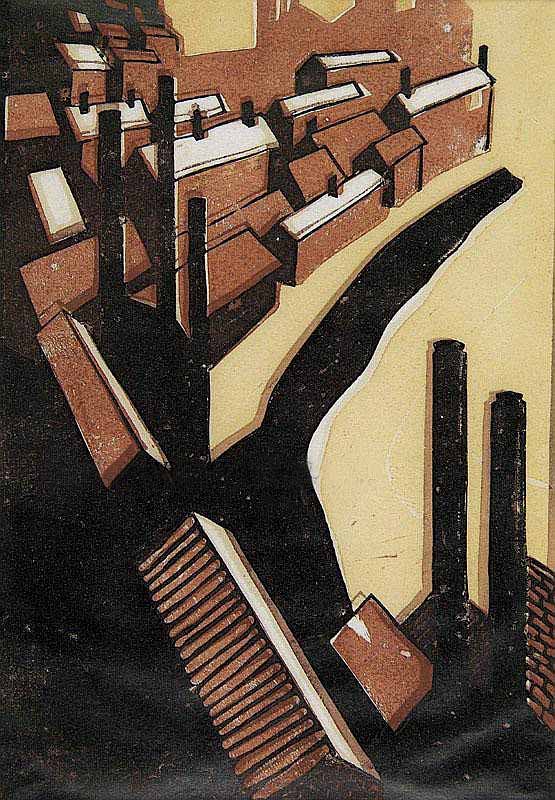

The view of Hamilton Street closely mirrors LS Lowry’s Street Scene Pendlebury – the mill looming large over the fierce perspective of the roadway. The importance of Lowry’s role in constructing a popular image of the North cannot be overestimated.

He finds a grim beauty in his views of red facades, black smoke and figures in white, snowy emptiness. He is a modern primitive, an industrial Rousseau, whose way of seeing is perhaps the only one that could do justice to the way places like Salford looked in the factory age.

For many years cosmopolitan London turned its back on Lowry, finally relenting with a one man show at the Tate in 2013 – I noted on the day of my visit, that the attendant shop stocked flat caps, mufflers and bottled beer, they seemed to have drawn the line at inflatable whippets.

Drawing upon other artists’s work, in a continuous search for ways to depict the unlovely facts of the city’s edges and the landscape made by industrialisation.

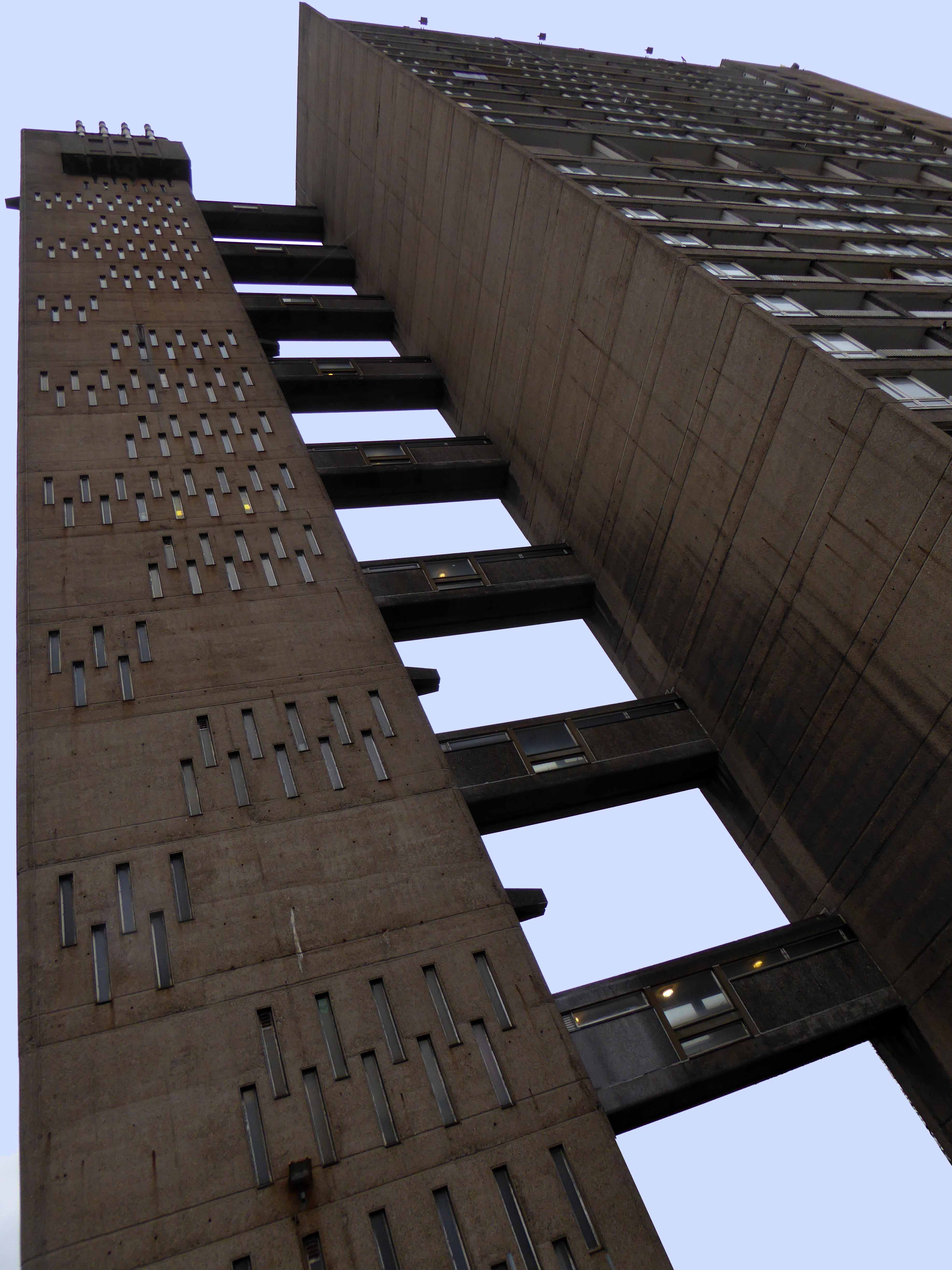

But Murdoch’s Hamilton Street is as much a construct as Lowry’s – the snow an expensive technical coating, Mr Beckham a CGI apparition. Our contemporary visual culture is littered with digital detritus, saving time and money, conjuring up cars, kids and footballers at will.

An illusion within an illusion of an illusory North.

Green screen chroma keyed onto the grey tableau.

Mr Beckham himself can also be seen as a media construct, for many years representing that most Northern of institutions Manchester United – itself yet another product of image manipulation, its tragic post-Munich aura encircling the planet, with an expensive Empire Made, red and white scarf of cultural imperialism.

David’s parents were fanatical Manchester United supporters who frequently travelled 200 miles to Old Trafford from London to attend the team’s home matches, he inherited his parents’ love of Manchester United, and his main sporting passion was football.

Mr B’s mentor was of course former Govan convener – Mr A Ferguson, who headed south to find his new Northern home, creating and then destroying the lad’s career, allegedly by means of boot and hairdryer.

Here we have the traditional Northern Alpha Male challenged by the emergent Metrosexual culture, celebrity fragrances, posh partner, tattooed torso, and skin conditioner endorsements.

It is to be noted that the wealth of the region, in part created by the shoemaking and electrical industries, have long since ceased to flourish, though still trading, PIFCO no longer has a local base.

The forces of free market monopoly capitalism have made football and its attendant personalities global commodities, and manufacturing by and large, merely a fanciful folk memory.

Hamilton Street would have provided substantial homes to workers at the Ryecroft Cotton Mills.

Ryecroft Mill, built in 1837,was the second of a series of four mills built on the site, the first was built in 1834. In 1843, over 10,000 people were employed in Ashton’s cotton mills – today there are none.

This industrial growth was far from painless and Ashton along with other Tameside towns, worked long and hard in order to build the Chartist Movement, fighting to establish better working conditions for all.

The tradition of political and religious non-conformity runs wide and deep here, the oft overlooked history of Northern character and culture.

Textile production ceased in the 1970s and the mill is now home to Ryecroft Foods, a subsidiary of Weetabix.

Ashton like many of Manchester’s satellite towns created enormous wealth during the Nineteenth and Twentieth centuries. The workers of Ashton saw little of that wealth, the social and economic void left by the rapid exodus of the cotton industry to the Far East, is still waiting to be filled, in these so called left behind towns.

Here is a landscape nestled in the foot of the Pennines, struggling to escape its past and define a future.