This spring at CUNY, my colleague Douglas Rushkoff and I will teach a course in Designing the Internet.

Students will propose and design a feature of the net they want to see. Some might start from the entrepreneurial perspective: a product, service, feature, or company. But I hope students will radically broaden their perspectives to design more: perhaps a regulatory regime, an ethical regime, a research agenda, a covenant of mutual obligation with the public for technology and media companies, a design agenda for equity and accessibility, business models built to avoid the corruptions we know, curricula, a warning from the past (about technological determinism or manifest destiny), archival standards, a manifesto for an open net, a constitution … anything. (Note that I did not list a metaverse, but if the students want to go there, they can.)

In the first third of the course, we will offer many readings — including the likes of Vannevar Bush, André Brock Jr., danah boyd, Charlton McIlwain, Siva Vaidhyanathan, Andrew Pettegree, Kate Klonick, David Weinberger, Ruha Benjamin, Theodor Adorno, Axel Bruns, James Carey, Dave Winer, Marshall McLuhan— and much discussion examining the net and how we got here: lessons for good and bad. We will invite guests from other perspectives and disciplines: anthropology, psychology, African-American studies, Latino studies, ethics, history, psychology, technology. The students will work on their proposals through the term and will present at the end.

Our idea is to demonstrate to students that they have the agency and responsibility for the future of the net. Because the course is being taught at the Newmark Graduate School of Journalism, I have a particular objectives for media students: to argue that the canvas for journalists and the service they provide is much wider than story-telling and publication. (I contend the net is not a subset of media but instead media are becoming — alongside so many other sectors of society — subsets of the network.) I also want to instill in journalists the reflex to seek out, learn from, and share work from academics who are researching key questions about the net and its impact — based on evidence. The students will find and share a work of research a week.

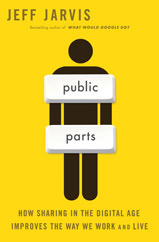

Doug and I come at this from different perspectives. I wrote the book What Would Google Do? Doug, a professor at Queens College, wrote the book Throwing Rocks from the Google Bus. Opinions may vary. But we end up on the same road: arguing that the net is not baked, that its present proprietors are not its forever owners, that we have the opportunity and responsibility to decide and design the net we want. We both want the net to be the province of humanity over technology. As Doug put it to me: “We just get there differently. I want less evil, you want more good.”

In the end, I believe that what we are examining is the future of society’s institutions, challenged and rebuilt or replaced in a new, networked reality. In my to-be-published (I pray) book The Gutenberg Parenthesis, I use this example:

The first recorded effort to impose censorship on the press came only about fifteen years after Gutenberg’s Bible. In 1470, Latin grammarian Niccolò Perotti appealed to Pope Paul II to impose Vatican control on the printing of books. His motive was not religious, political, or moral “but exclusively a love of literature” and a desire for “quality control,” according to Renaissance historian John Monfasani. Conrad Sweynheym, a German cleric who, it is believed, worked with Gutenberg in Eltville, and his partner, Arnold Pannartz, became the first to print a book in Italy, in 1465. Two years later, they moved to Rome, where in 1470 they published an edition of Pliny’s Natural History edited by Andrea Bussi. It was this book that set Perotti off. In his litany of complaint to the pope, he pointed to twenty-two grammatical errors in the book, which much offended him.

Perotti had been an optimist about this new technology of printing, having “once viewed as a boon to literature ‘the new art of writing lately brought to us from Germany.’” He called it “a great and truly divine benefit” such that he “hoped that there would soon be such an abundance of books that everyone, however poor and wretched, would have whatever was desired.” But the first tech backlash was not long in coming, for according to Monfasani, Perotti’s “hopes have been thoroughly dashed. The printers are turning out so much dross…. And when good literature does get printed, he complains, it is edited so perversely that the world would be better off not having the texts than to have them circulate in corrupt editions of a thousand copies.” Perotti had a solution. He called upon Pope Paul to appoint a censor, not to ban books so much as to improve them. “The easiest arrangement is to have someone or other charged by papal authority to oversee the work, who would both prescribe to the printers regulations governing the printing of books and would appoint some moderately learned man to examine and emend individual formes before printing,” Perotti wrote. “The task calls for intelligence, singular erudition, incredible zeal, and the highest vigilance.”

We might look upon Perotti’s call as quaint — not unlike Yahoo in the early days of the web thinking its librarians could catalogue every single noteworthy site anyone could ever make. The idea that a moderately learned if vigilant person could approve and correct all printing even out of Rome alone betrays a failure to divine the scale of printing to come. Yet one could say that rather than foreseeing the state censor, Perotti was envisioning the roles of the editor and publishing house as means to assure quality. He was looking to invent a new institution to solve a new problem, just as we must today. Fact-checkers engaged by Facebook and algorithms written at every internet company are inadequate to the task of assuring credibility of content, just as Perotti’s censor would have been. So what do we invent instead?

That is the question we will address in this course.

The course will be open to any CUNY graduate students from any discipline and, with approval, to undergrads and (if there is space) nonmatriculated members of the public (non-CUNY students can follow this link or DM me or Doug).

We hope this is a pilot for a much larger project in Internet Studies — perhaps a degree. We are also working with others on efforts to bring more attention to internet research: We plan to offer literature reads of prominent and current work to journalists and policymakers to inform their work with evidence (I’ll share a job posting shortly). And once COVID allows, we hope to bring together researchers to share perspectives on what we know and don’t know about the impact of the net, what questions we have yet to ask, and what data and access are needed to explore those questions. More to come, as I’m still raising funding for the work. (Disclosure: My school and center have received funding for scholarships and various activities from Facebook, Google, and Craig Newmark; I receive no remuneration from any tech platform.)

In the meantime, teaching this course alongside Doug will be a blast.