To begin at the beginning – some years ago I traced the route of the River Medlock, I chanced upon a forlorn pub called The River, all alone, desolate and boarded up, presiding over an area that I assumed, would once have supplied ample trade to a busy boozer.

I returned last week in search of some rhyme or reason, for such a seemingly sad and untimely decline.

So here we are back at in Manchester 1813, the seeds of the Industrial Revolution sewn in adjacent Ancoats, the fields of Beswick still sewn with seeds, the trace of Palmerston Street nought but a rural track.

Sited on land between Great Ancoats Street and Every Street was Ancoats Hall, a post-medieval country house built in 1609 by Oswald Mosley, a member of the family who were Lords of the Manor of Manchester. The old timber-framed hall, built in the early 17th century, and demolished in the 1820s was replaced replaced by a brick building in the early neo-Gothic style.

This would become the Manchester Art Museum, and here the worst excesses Victorian Capitalism were moderated by philanthropy and social reform.

When the Art Museum opened, its rooms, variously dedicated to painting, sculpture, architecture and domestic arts, together attempted to provide a chronological narrative of art, with detailed notes, labels and accompanying pamphlets and, not infrequently, personal guidance, all underlining a sense of historical development.

Housing and industry in the area begins to expand, railways, tramways, homes and roads are clearly defined around the winds of the river.

In 1918 the museum was taken over by the city, it closed in 1953 and its contents were absorbed into the collection of Manchester City Art Gallery, as the State increasingly took responsibility for the cultural well being of the common folk.

The building was finally demolished in the 1960’s – just as the area, by now a dense warren of back to back terraces, was to see further change.

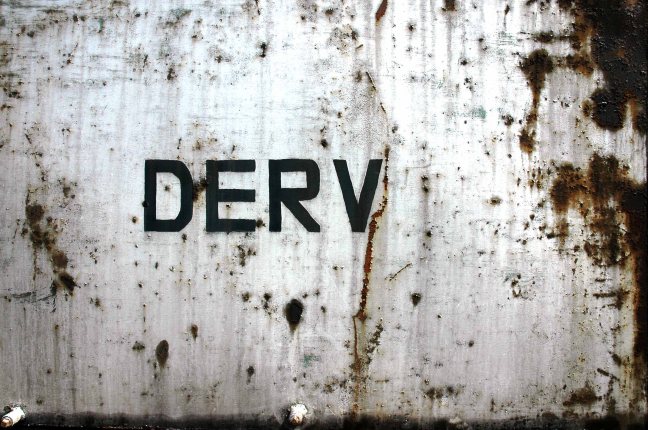

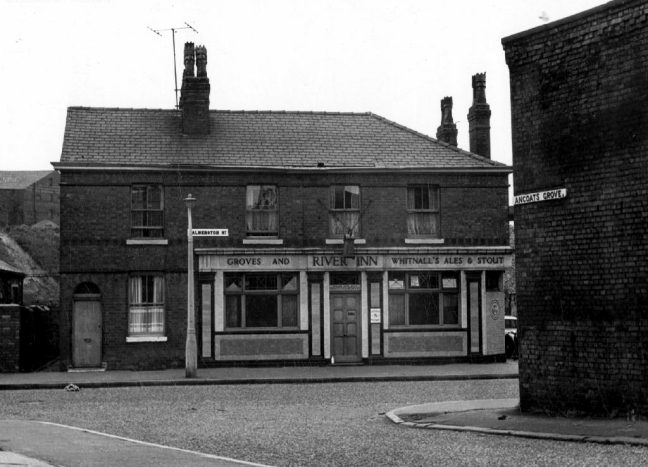

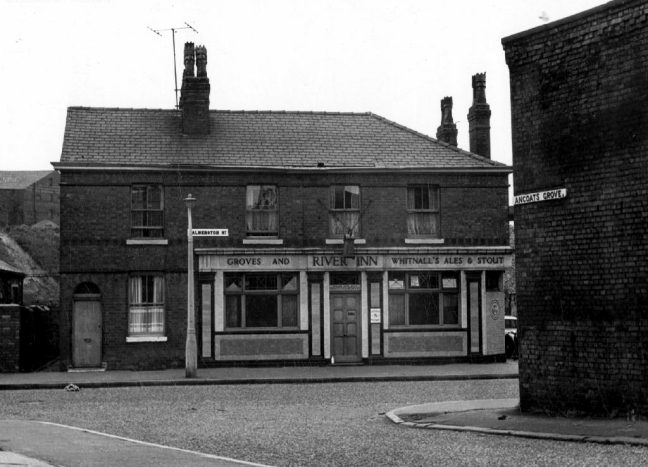

Along the way was the the River Inn, seen here with a fine Groves and Whitnall’s faience tiled frontage.

The street also offered rest, relaxation and refreshment through the Church, Pineapple and Palmerston pubs, as recored here on the Pubs of Manchester blog.

The River seen here in the 1970’s struggled on until 2007.

Further along we find the Ardwick Lads Club, further evidence of the forces of social reform, that sadly failed to survive the forces of the free market and the consequent Tory cuts in public spending and wilful Council land-banking.

The Ardwick Lads’ and Mens’ Club, now the Ardwick Youth Centre, opened in 1897 and is believed to be Britain’s oldest purpose-built youth club still in use [and was until earlier in 2012]. Designed by architects W & G Higginbottom, the club, when opened, featured a large gymnasium with viewing gallery – where the 1933 All England Amateur Gymnastics Championships were held – three fives courts, a billiard room and two skittle alleys (later converted to shooting galleries). Boxing, cycling, cricket, swimming and badminton were also organised. At its peak between the two world wars, Ardwick was the Manchester area’s largest club, with 2,000 members.

On the 10th September 2012 an application for prior notification of proposed demolition was submitted on behalf of Manchester City Council to Manchester Planning, for the demolition of Ardwick Lads’ Club of 100 Palmerston Street , citing that there was “no use” for the building in respect to its historic place within the community as providing a refuge and sporting provision to the young of Ancoats.

At the top turn of the street stood St Mary’s – the so called Lowry church.

Used as a location for the film adaptation of Stan Barstow’s A Kind Of Loving

The homes and industry attendant schools and pubs were soon to become history, all that you see here is more or less gone. Slum clearance, the post-war will to move communities away from the dense factory smoke, poor housing stock and towards a bright shiny future elsewhere.

Whole histories have subsequently been subsumed beneath the encroachment of buddleia, bramble, birch and willow.

The land now stands largely unused and overgrown, awaiting who knows what, but that’s another tale for another day.

Archive images from the Manchester Local Image Collection.