New Physics 🧵! Ludwig Boltzmann was not just a father of Statistical Physics but also a master of Thermodynamics. That’s how he got his name on the Stefan-Boltzmann law. If you allow me, I would love to walk you through a magic moment in physics history. /1

Conversation

Replying to

Let’s begin with the law itself, which says something about the light emitted by hot bodies—like glowing pokers or the sun. Specifically, let us look at the power (energy per time) such a body emits per unit area of its surface. That’s called the radiant emittance, j. /2

4

12

197

In 1879, Josef Stefan experimentally showed that this radiant emittance is proportional to the fourth power of the temperature: j = σT⁴. The hotter a body is, the very much more energy it emits. /3

3

7

199

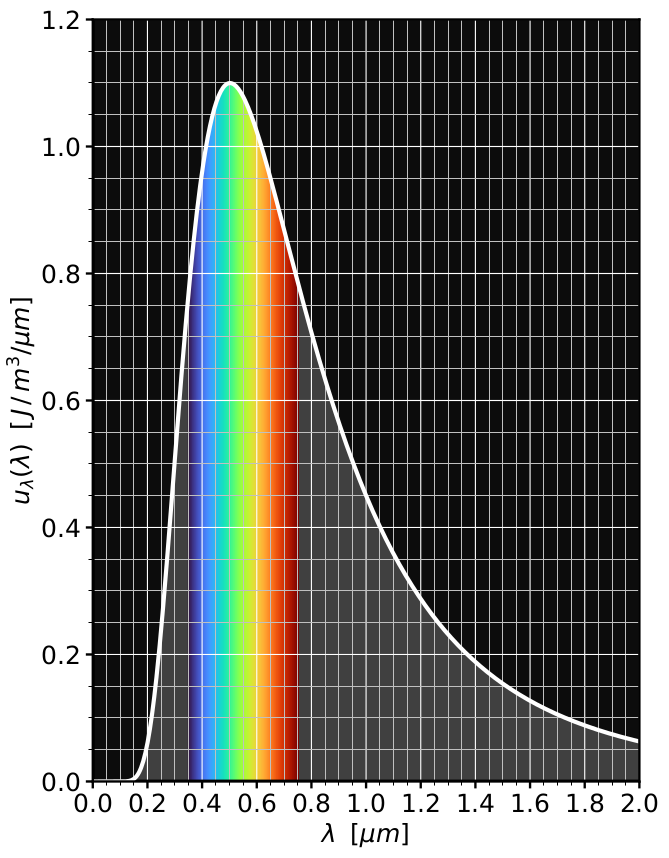

Modern Physics students tend to learn of this law as a simple corollary of Planck’s black body spectrum—how much power is emitted per unit area and PER WAVELENGTH, meaning, how much light do we get at different colors. /4

3

12

231

All you need to do is to integrate Planck’s formula over all wavelengths and, voilà, out pops the Stefan-Boltzmann law j = σT⁴. /5

2

4

193

Here’s where it gets interesting, though. Planck derived his black body spectrum in 1900, and he needed to invent a key idea of quantum mechanics to do so: photons! But Boltzmann published his explanation in 1884—16 years earlier! How could he? /6

3

4

190

Boltzmann used an exceedingly beautiful thermodynamic argument that did not require him to know quantum mechanics. Let me walk you through it now. Warning: some math and thermodynamics ahead, but I’ll try hard to make it palatable, promised!!! /7

2

4

223

Boltzmann started from three ideas: (1) thermal radiation as a thermodynamic system is “extensive”; (2) the pressure is ⅓ of the radiation’s energy density; and (3) the chemical potential vanishes. Uh oh. What does this even mean? /8

2

4

163

The first idea simply says that the energy content of radiation scales with size. If you have two hot ovens of the same temperature, filled with thermal radiation, and the second one has twice the VOLUME of the first, then its radiation content also has twice the ENERGY. /9

1

3

147

The second idea quantifies the notion of “radiation pressure”: light can push you! Maxwell realized in 1874 that it follows from his equations, and Adolfo Bartoli gave a thermodynamic argument two years later—which Boltzmann had heard about. /10

2

4

153

The third idea is the most elusive: the chemical potential μ essentially describes the thermodynamic cost of adding a particle to a system. But where are the particles in radiation? Boltzmann didn’t know anything about photons! /11

1

4

145

I’ve never fully understood how Boltzmann exactly reasoned, but he must have intuited that the non-particleness of light means that μ must vanish. In modern parlance we would say “photon number isn’t conserved”. Maybe it was just a lucky guess? /12

5

3

151

Anyways, with these three ideas we’re ready to roll! Boltzmann first began by considering the internal energy U as a function of three legitimate variables: temperature T, volume V, and chemical potential μ. Let’s write this as U(T,V, μ). /13

2

3

127

If—according to idea 3—the chemical potential vanishes, we can drop the μ and simply write U(T,V). And if this is supposed to be extensive—by idea 1—then it must be proportional to volume: U(T,V) = V u(T), with a function u(T) that only depends on temperature. /14

1

3

121

Next, extensivity also implies that Euler’s equation holds for the energy:

U = TS – PV + μN

It is a consequence of the properties of homogeneous functions (and “extensive” implies “homogeneous”). Here, S is the entropy, which will feature prominently in just a sec. /15

2

3

118

There’s one more idea to use—number 3—which says that the pressure equals ⅓ of the energy density. It implies that P = ⅓U/V = ⅓uV/V = ⅓u. /16

1

3

104

OK, let’s now put all this together! With μ = 0, we can drop the μN term in Euler’s equation, and with PV = U/3 we can replace the second one: U = TS – U/3. We can then solve this equation for the entropy:

S = 4U / 3T = (4V/3) u(T)/T

/17

1

3

106

The final stroke of genius is that Boltzmann used a “Maxwell relation”—one of these eternally behated but really quite trivial integrability conditions that come for free with every thermodynamic potential. Let me show you how! /18

1

3

118

Ignoring particle number and chemical potential (μ = 0, remember?), the free energy of a system is a function of temperature and volume: F(T,V). It is a thermodynamic potential, because we can get entropy and pressure by differentiating it: /19

1

3

107

S = –dF/dT and P = –dF/dV. That’s bread-and-butter in thermodynamics. The trick is to AGAIN differentiate S with respect to V and P with respect to T. This in both cases is just two derivatives of F, WHICH COMMUTE!, and so the answer must be the same! /20

2

5

111

In other words, we get the identity

(dS/dV)_T = (dP/dT)_V

Where the “_T” and “_V” parts simply remind us of the other variable we’re not differentiating.

All we now need to do is insert what we derived above about thermal radiation into this identity! /21

1

4

103

First, if P = u(T)/3, then (dP/dT)_V = u’(T)/3, where the ’ is just a temperature derivative. And if S = (4V/3) u(T)/T, then (dS/dV)_T = (4/3) u(T)/T. But these two expressions are equal! Canceling the 1/3, we get

u’(T) = 4 u(T)/T

/22

1

4

112

Notice what we’ve done! We derived a differential equation for u(T)! In fact, a very simple one that can be solved by a power-law “ansatz” and immediately leads to the solution

u(T) = a T⁴

where “a” is some unknown constant of integration. /23

1

4

125

BOOM! This is basically our answer! To get it in full final glory, we use that the radiant emittance is j(T) = ¼cu(T), where c is the speed of light. Why is that? Because flux is always the density of what’s fluxing times the speed at which it’s fluxing—here: light speed! /24

1

5

111

And where does the ¼ come from? Ah, that’s because, first, we’re only interested in the flux coming our way, not the one in the opposite direction (one factor of ½), and we also need to project all angles onto the normal to the surface (another factor of ½). /25

1

4

95

But let’s not get sidetracked by boring nitty gritty stuff! The key wonder is that we just derived the T⁴ dependence! Thermodynamically! How could we do that without ever breathing the words “quantum mechanics”? /26

1

3

104

There are two answers. First, it’s of course hidden in the underlying ideas (“equations of state”) Boltzmann relied on, maybe most prominently in the inspired guess that μ = 0. And second: it’s hiding in that unknown integration constant a! /27

1

5

97

One of the pleasing consequences of Planck’s law is that it predicts the prefactor in the Stefan-Boltzmann law. And, OF COURSE, it contains Planck’s constant! There’s no way Boltzmann could have put that in—but he needn’t! /28

1

4

96

It is hard for me to adequately express how very beautiful I think this derivation is. Hendrik A. Lorentz called it a “a true pearl of physics” (“eine wahre Perle der Physik”). In fact, Lorentz was the first to add Boltzmann’s name to the Stefan-Boltzmann law. /29

2

6

144

Permit me to conclude with a more “philosophical” outlook, but one that’s very dear to my heart. The fact that Boltzmann could derive this law, which has deep quantum mechanical roots, without knowing anything about quantum mechanics, is very profound. /30

1

5

153

It speaks to the true power of thermodynamics that it lets us discover and explain laws of nature without knowing details of their underlying “microscopic realization”. We don’t always need to know what’s going on “deep down”! /31

11

17

306

Show replies