Keynes was not a Keynesian. He was a Post Keynesian!

from Lars Syll

But these more recent writers like their predecessors were still dealing with a system in which the amount of the factors employed was given and the other relevant facts were known more or less for certain. This does not mean that they were dealing with a system in which change was ruled out, or even one in which the disappointment of expectation was ruled out. But at any given time facts and expectations were assumed to be given in a definite and calculable form; and risks, of which, tho admitted, not much notice was taken, were supposed to be capable of an exact actuarial computation. The calculus of probability, tho mention of it was kept in the background, was supposed to be capable of reducing uncertainty to the same calculable status as that of certainty itself …

Thus the fact that our knowledge of the future is fluctuating, vague and uncertain, renders Wealth a peculiarly unsuitable subject for the methods of the classical economic theory.

And this emphasis on the importance of uncertainty is not even mentioned in ‘IS-LM Keynesianism’ …

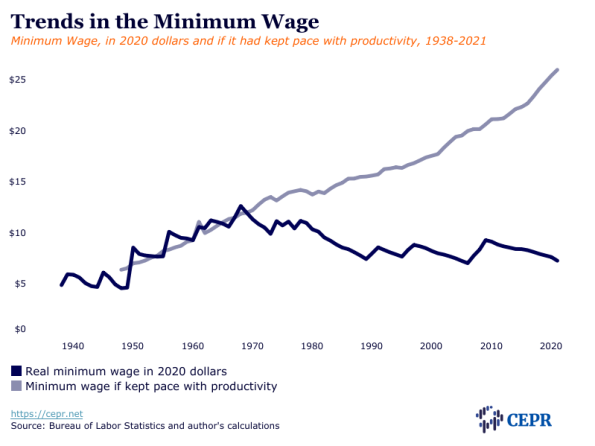

The $26 an Hour Minimum Wage

from Dean Baker

That may sound pretty crazy, but that’s roughly what the minimum wage in the United States would be today if it had kept pace with productivity growth since its value peaked in 1968. And, having the minimum wage track productivity growth is not a crazy idea. The national minimum wage did in fact keep pace with productivity growth for the first 30 years after a national minimum wage first came into existence in 1938.

Furthermore, a minimum wage that grew in step with the rapid rises in productivity in these decades did not lead to mass unemployment. The year-round average for the unemployment rate in 1968 was 3.6 percent, a lower average than for any year in the last half century.

Sapere aude!

from Lars Syll

Enlightenment is man’s emergence from his self-imposed nonage. Nonage is the inability to use one’s own understanding without another’s guidance. This nonage is self-imposed if its cause lies not in lack of understanding but in indecision and lack of courage to use one’s own mind without another’s guidance. Sapere aude! “Have the courage to use your own understanding,” is therefore the motto of the enlightenment.

Laziness and cowardice are the reasons why such a large part of mankind gladly remain minors all their lives, long after nature has freed them from external guidance … Those guardians who have kindly taken supervision upon themselves see to it that the overwhelming majority of mankind — among them the entire fair sex — should consider the step to maturity, not only as hard, but as extremely dangerous. First, these guardians make their domestic cattle stupid and carefully prevent the docile creatures from taking a single step without the leading-strings to which they have fastened them. Then they show them the danger that would threaten them if they should try to walk by themselves. Now this danger is really not very great; after stumbling a few times they would, at last, learn to walk. However, examples of such failures intimidate and generally discourage all further attempts …

Dogmas and formulas, these mechanical tools designed for reasonable use — or rather abuse — of his natural gifts, are the fetters of an everlasting nonage … Read more…

Weekend read – The evolution of ‘big’: How sociality made life larger

from Blair Fix

The game I play is a very interesting one.

It’s imagination in a tight straitjacket.

Like Richard Feynman’s game of science, evolution is stuck in a straitjacket. It is driven by chance. But evolution is not free to explore every path.

Take, as an example, the evolution of organism size. While it seems like there are many routes to bigness, I propose that there is fundamentally only one: sociality. In the march towards ever-larger organisms, there have been three major revolutions. All of them involved the merger of previously autonomous organisms into a new communal creature. I call this route to bigness ‘size through sociality’. It is a tale 4 billion years in the making.

The drive towards sociality, I argue, is a response to a basic feature of geometry. As objects get larger, their volume grows faster than their surface area. This fact of space causes problems for harvesting energy. It requires that big organisms harness and distribute energy on a limited surface-area budget. The easiest way to solve this problem, it seems, is to merge existing structures. Hence the evolution of bigger life is deeply connected to the evolution of sociality.

The evolution of ‘big’ is also connected to human culture.

Modern human institutions may represent a new transition in the evolution of life — a transition from massive organisms to supermassive superorganisms. But as with the rest of life, this evolution occurs in a straitjacket. The size distribution of human institutions seems to follow the same pattern as the size distribution of other organisms. In fact, it is an extension of this pattern, upping the size of life to new proportions.

In this light, human cultural evolution may be a variation on an old theme: size through sociality.

The tyranny of geometry

As I child, I loved playing with toy cars. I made the little vehicles jump over great distances, usually with the gleeful hope that they might explode. But the toys always took the beating with ease. When I imagined doing the same stunt with life-sized cars, however, I knew that they couldn’t withstand the punishment. But I didn’t know why.

Today I do. It’s because the size of an object changes how it behaves. The reason owes to a simple feature of geometry. As objects get larger, their volume grows faster than their area. This fact affects the objects’ properties. Read more…

Behavioural economics and complexity economics

from Lars Syll

What is to take the place of neoclassical economics and its neoliberal policy offshoot? There is no shortage of candidates, grouped under the broad banner of economic heterodoxy. Some of these successor doctrines – behavioral economics and complexity economics are examples of note – take the neoclassical orthodoxies as a point of departure. They therefore continue to define themselves in relation to those orthodoxies. Others avoided the gravitational pull altogether – or, as in the exceptional case of Keynes, made a “long struggle to escape”. The behaviorists depart from neoclassicism by giving up strict assumptions of rational and maximizing behavior. Complexity theorists explore the dynamics of interacting agents and recursive functions. Both achieve a measure of academic reputability by remaining in close dialog with the orthodox mainstream. Neither pays more than a glancing tribute to earlier generations or other canons of economic thought. The model is that of neoclassical offshoots – New Institutionalism, New Classical Economics, New Keynesianism – that make a vampire practice of colonizing older words and draining them of their previous meaning. The dilemma of these offshoots lies in having accepted the false premise of the orthodoxy to which it proposes to serve as the alternative. The conceit is of a dispassionate search for timeless truth, once again pursued by “relaxing restrictive assumptions” in the interest of “greater realism”. Thus, for example, in complexity theories agents follow simple rules and end up generating intricate and unpredictable patterns, nonlinear recursive functions give the same result, the variance of returns turns out to be non-normal, and so forth. But once the starting point is taken to be the neoclassical competitive general equilibrium model, these exercises are largely drained of insight and relevance. The behaviorists can tell us that real people do not appear to fit well into the portrait of autonomous, selfish, commodity-obsessed pleasure-seekers that is “economic man”. The complexity theorists can tell us, as Arthur (2021) does, is that a system constructed from confections of interacting agents may be unstable. These things, even the dimmest observer of real-existing capitalism already knew.

Although discounting empirical evidence cannot be the right way to solve economic issues, there are still, in my opinion, a couple of weighty reasons why we — just as Galbraith — perhaps shouldn’t be too excited about the so-called ’empirical’ or ‘behavioural’ revolution in economics. Read more…

Diversity in economics

from Peter Radford

In this case geographical diversity.

Dani Rodrik has brought to our attention a rather serious problem within the economics profession: it is still dominated by people living and working in the West. As a consequence it has a decided bias towards issues that are of significant interest to the West.

This is, of course, not news to any of you not living in the West. Nor is it news to anyone outside the profession paying attention to the product of the journals and various other outlets. The ideas that get the most attention and the work that gets most lauded is still channeled through a very narrow lens. The result is a considerable — massive? — underrepresentation of viewpoints and experiences that inhibit the ability of the discipline to engage broadly with the world.

I cannot dispute Rodrik’s conclusion:

“Economics is currently going through a period of soul searching with respect to its gender and racial imbalances. Many new initiatives are underway in North America and Western Europe to address these problems. But geographic diversity remains largely absent from the discussion. Economics will not be a truly global discipline until we have addressed this deficit as well.”

He is absolutely correct. More power to him for bringing this to the fore.

The problem is that Rodrik lives and works within that very narrow space he suggests cramps the discipline. Well done him. But there is a sense of something missing from his short article. Read more…

Learning to re-envisage the economy (Part 2)

from David Taylor and WEA Pedagogy Blog

Looking now at anticipations of Shannon’s information systems in recent economic research, Maria Madi found American pragmatist C. S. Peirce studying scientific logic cycles and semiotics (signalling) in 1873. In the latest Real Word Economic Review, Katherine Farrell found Marshall starting economics from everyday life (small is beautiful) instead of the funding of government. Andri Stahel started from Aristotle and found Dilthey studying hermeneutics (Shannon’s decoding). However, the story told about computing is that Babbage showed it to be a mechanism, which Turing turned into a tape recorder using von Neumann’s architecture and linear programming. Unsurprisingly, Shannon does not surface in Jamie Galbraith’s brilliant survey of current economics, nor in Edward Fullbrook’s textbook proposal: both still seeing the economy as it still is, so how it is usually seen. Like a centralised power distribution system, primarily supplying governments and big business. Read more…

“Power and Influence of Economists”

from Mitja Stefancic and current issue of WEA Commentaries

“Power and Influence of Economists: Contributions to the Social Studies of Economics”, edited by J. Maesse et al reflects upon the multifaceted relationships that exist between science and society – a domain in which economic experts play a very influential role and often have a direct impact on society by and large. It offers complex insights into the forms of power in economics and provides a broad overview of recent developments in the evolving field of social studies of economics. The book comprises 14 chapters, which are grouped into four main parts: a) Economic knowledge and discursive power; b) Economic governmentalities; c) Economists in networks; d) Economics as a scientific field. Each chapter takes a detailed view on the multiple dimensions of power, action and impact with reference to economics.

Among several notable accomplishments, the volume brings forward two themes that have been singled out in this review, as they are of particular interest to social scientists and, thus, worth commenting on. On the one hand, it provides evidence on how some countries have become laboratories for economic experiments, for instance in the application of the politics of austerity orchestrated by influential economists and policy makers. On the other hand, the book shows that economics is a field of power in which powerful networks play a role in determining who may be publicly recognized as a successful economist, i.e. an expert worth reading and listening to, and, by contrast, identifying those who shall not enjoy such attention among colleagues or such visibility in mainstream media.

. . . . . .

Selected quotes from the volume Read more…

Evolutionary and biophysical economics

from James Galbraith

The evolutionary and biophysical approach to economic phenomena is not a new thing, and actually long predates the neoclassical orthodoxy from which some believe it now springs. It began with the intellectual interplay of Malthus and Darwin, developed through Marx and Henry Carey and (to a degree) in the work of the German Historical School, brewed and fermented in the pragmatic and pluralist effervescence of late 19th century American philosophy, and achieved a first full articulation in the hands of Thorstein Veblen (1898). It thereafter developed in the Institutionalist tradition of John R. Commons (1934) and Clarence E. Ayres (1944), among many others, and emerged as the dominant intellectual force in American economics under the New Deal. Read more…

Learning to re-envisage the economy (Part 1)

from David Taylor and WEA Pedagogy Blog

After the invention of printing, pedagogy began with Machiavelli’s The Prince teaching politicians to lie, and Francis Bacon’s The Advancement of Learning advising a new king to develop an encyclopedia of science “for the glory of God and the relief of Man’s estate” by “taking things to bits to see how they worked”. Bacon’s doctor Harvey took men’s bodies to bits and discovered the circulation of the blood. In France, Descartes took brains to bits, envisaging a “spiritual” mind (what we would now call information) controlling the brain’s matter.

Economics began to go wrong when Locke denied Descartes’ “spirit”, mistaking Newton’s proving his gravitational hypothesis by observation for his starting with a “blank slate”; perhaps seeing that people having learned to see money as gold enabled would-be princes and mass producers to win wars using Bank of England credit. Hume then denied Bacon’s unobservable God and his friend Adam Smith that Men who had fallen on hard times should be relieved; the new “princes” replaced invisible rights with written laws, certificates of authority and deeds of ownership. The subsequent scientific discoveries of invisible flows in electric circuits, electro-magnetism, radio communication, electric circuit logic and the creation of information and environmental sciences passed them by except insofar as they could make money from them. So did mass production far exceeding the world’s capacity for self-renewal. Read more…

Behavioral economics and complexity economics

from James Galbraith

What is to take the place of neoclassical economics and its neoliberal policy offshoot? There is no shortage of candidates, grouped under the broad banner of economic heterodoxy. Some of these successor doctrines – behavioral economics and complexity economics are examples of note – take the neoclassical orthodoxies as a point of departure. They therefore continue to define themselves in relation to those orthodoxies. Others avoided the gravitational pull altogether – or, as in the exceptional case of Keynes, made a “long struggle to escape”.

The behaviorists depart from neoclassicism by giving up strict assumptions of rational and maximizing behavior. Complexity theorists explore the dynamics of interacting agents and recursive functions. Both achieve a measure of academic reputability by remaining in close dialog with the orthodox mainstream. Neither pays more than a glancing tribute to earlier generations or other canons (Reinert, Ghosh and Kattel, 2016) of economic thought. The model is that of neoclassical offshoots – New Institutionalism, New Classical Economics, New Keynesianism – that make a vampire practice of colonizing older words and draining them of their previous meaning. Read more…

Life at the bottom in Joe Biden’s America – 2 charts

from Dean Baker

With the economy facing substantial bottlenecks, and the continuing spread of the pandemic, it is worth taking a quick look at how lower paid workers have been faring. Nominal wages have been rising rapidly for workers at the bottom of the pay ladder in recent months. This has allowed workers in the lowest paying jobs to see substantial increases in real wages, in spite of the uptick in inflation the last few months.

Here’s the picture in retail for production and non-supervisory workers. Note that real wages were actually somewhat lower in 2018 than they had been in 2002. (These numbers are 1982-1984 dollars, so multiply by about 2.6 to get current dollars.) They did rise in 2018 and 2019, due to a tightening of the labor market, as well as minimum wage hikes at the state and local level. The impact of the pandemic and the recovery has been a big net positive. Real wages in the sector are roughly 4.6 percent higher than the level of two years ago, a 2.3 percent annual real wage gain. Read more…

Changing the conceptions of morality and reality associated with economics

from Richard Norgaard

Economism has been modern capitalism’s myth system, or in computer parlance, capitalism’s operating system. It has stressed utilitarian moral beliefs compatible with economic assumptions that are critical to neoclassical economic theories. These beliefs include the idea that society is simply the sum of its individuals and their desires, that people can be perfectly, or at least sufficiently, informed to act rationally in markets, that markets balance individual greed for the common good, and that nature can be divided up into parts and owned and managed as property without systemic social and environmental consequences (Norgaard, 2019). Especially after World War II when the industrialized nations globally organized around economic beliefs and set out to spread their economic systems among less industrialized nations, these simple beliefs steadily displaced more complex moral discourses of traditional religions (Cobb, Jr, 2001). Economism has facilitated climate change and other anthropogenic drivers of rapid environmental change. Natural scientists are labeling current times the Anthropocene. I advocate using the term Econocene since our economic beliefs, both moral and those with respect to reality, and the econogenic drivers they facilitated have been critical to the rise of rapid environmental change. Furthermore, the term Econocene alludes to the current social and technological structures and human capital that are sustained by economism.[1] Escaping the Econocene will require dynamically, polycentrically, reconnecting reality and morality writ large. Read more…

A revolutionary change in economics is long overdue.

from Clive Spash and Adrien Guisan

Economics has become increasingly detached from its object of study and the orthodoxy is fundamentally flawed as a social science because it advocates a prescriptive methodology while lacking any serious engagement with epistemology and ontology. The resulting epistemic fallacy means it promotes a narrow implicit world view as if a factual truth. Failures here include imposition of limited quantitative methods and mathematically formalist methodology that exclude qualitative aspects of reality and the use of isolated/closed systems thinking for an open system reality. Read more…

Weekend read: What caused the stagflation of the 1970s? Answer: Monetarism

from Philip George

If any one event can be said to have knocked Keynesian economics off the high perch it occupied during the 1950s and 1960s it was the stagflation of the 1970s.

Keynes held that when aggregate demand fell due to a fall in business investment the government could stimulate the economy by increasing its own spending and lowering interest rates. Inflation would kick in only when the economy approached full employment. Monetarists questioned the ability of the government to control the business cycle through fiscal spending or loose monetary policy. They held that loose monetary policy could affect output only in the short run, and that in the long run it would only result in inflation. When the US economy simultaneously experienced both high unemployment and high inflation in the1970s, monetarism seemed to have triumphed.

If Keynesians had no policy or theoretical response to monetarists it was because they thought of money in the same way as monetarists did, as exemplified in the image below. Read more…

PPP exchange rates are riddled with problems

from Jayati Ghosh and current issue of RWER

As I have written elsewhere (Ghosh, 2018) while PPP exchange rates appear to control for differences in price levels and standards of living in different countries, they are riddled with conceptual, methodological and empirical problems. They assume that the structure of each country’s economy is similar to that of the benchmark country (the US) and changes in the same way over time beyond the reference year, which is clearly wrong across advanced and developing economies. The absence of weights within basic headings of goods and services, including the lack of representative weights, can result in these basic headings being priced using high-priced unrepresentative goods that are rarely consumed in some countries (Angus Deaton has provided the example of packaged corn flakes, which are available in poor countries, but only accessed by a relatively small minority of rich people). Country PPP rates are constructed from the prices of basic headings using expenditure weights from the national accounts – but these do not reflect the consumption patterns of people who are poor by global standards. While the current PPP measure does try to differentiate across regions, the different regions are linked using the region-wide ‘super’ PPP rates, which generate, for example, a price level for all of (say) Asia relative to the OECD countries—far too aggregative in a very disparate region to be at all accurate. There are additional concerns about the nature and coverage of the surveys that are conducted to establish the price levels in each country.

There is a further, and possibly even more damning, conceptual issue. Read more…

Steps toward an alternative paradigm

from Peter Söderbaum and current issue of WEA Commentaries

Mainstream neoclassical economics is a scientific but at the same time political paradigm. It is based upon specific normative assumptions about the individual, focusing on self-interest and maximizing utility, the firm maximizing monetary profits, and at an aggregate level, growth in Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Focus is on markets and behaviour in relation to markets. Markets are understood mechanistically in terms of the forces of supply and demand.

When taught at universities and elsewhere, neoclassical economics plays a role of making a specific ideology legitimate not only for students but also politicians and in society more generally. Self-interest is good for society, increased monetary profits in business is believed to be good for all of us by strengthening the economy. Something similar holds for ‘economic growth’ in GDP- terms. Entrepreneurship in monetary terms is celebrated and policy issues can be solved by privatization of public assets or the social construction of new markets. In this way neoclassical theory and method is close to mainstream neoliberalism as political ideology. Read more…

Repairing blackboard economic theory is not enough – 5 charts

from Richard Parker and current issue of RWER

Here at Harvard over the years, I’ve also certainly seen an ascent of what one might well call “neoliberalism” not just in economics but political science and political philosophy – and (this is not unimportant or unrelated), in both the university’s administration and in students’ assumptions about “the real world” they’ll enter after graduation (about which I’ll say more later). Today, after the Great Recession and still in the COVID Crisis, while I’m not sure I’m seeing neoliberalism’s fall, I know I am looking at a far more confused and confusing landscape of fragmented ideas. It’s a fragmentation one of you might argue that’s a mutation or neoliberal variant (COVID inspires thoughts of neoliberalism as a virus) – but it’s also, I think a landscape that nonetheless contains possibilities for real change.

Contexts (economic and political) we ignore at our peril

Economics can no longer evade political economy

from Jamie Morgan and current issue of RWER

If climate emergency indicates anything, it is that we are urgently in need of an economics that is “fit for purpose”. Consider what “fit for purpose” now means. An adequate economics now has to be one that helps us understand the difficult decisions that are likely to confront us in the coming years. On a global scale we are going to have to leave fossil fuels in the ground, restore aquifers and water systems, reinvigorate ecosystems, greatly accelerate reforestation, bring a halt to using the oceans as a dumping site for plastics and numerous other chemical pollutants, reduce acidification of the oceans and so on. But fundamentally, on a global scale we are, unless there is some miraculous technological miracle, going to have to do less. That means we cannot continue with throwaway consumerism or with continual economic-material-energy growth. We are going to have to use durable, replaceable and repairable goods, but more fundamentally we are going to have to consider our consumption decisions differently in regard of whether we buy something at all – since this seems basic to “low impact living”. This, however, is antithetical to both the system as is and the mechanisms and interests that currently “keep the economy going”.

Recent Comments