Success!

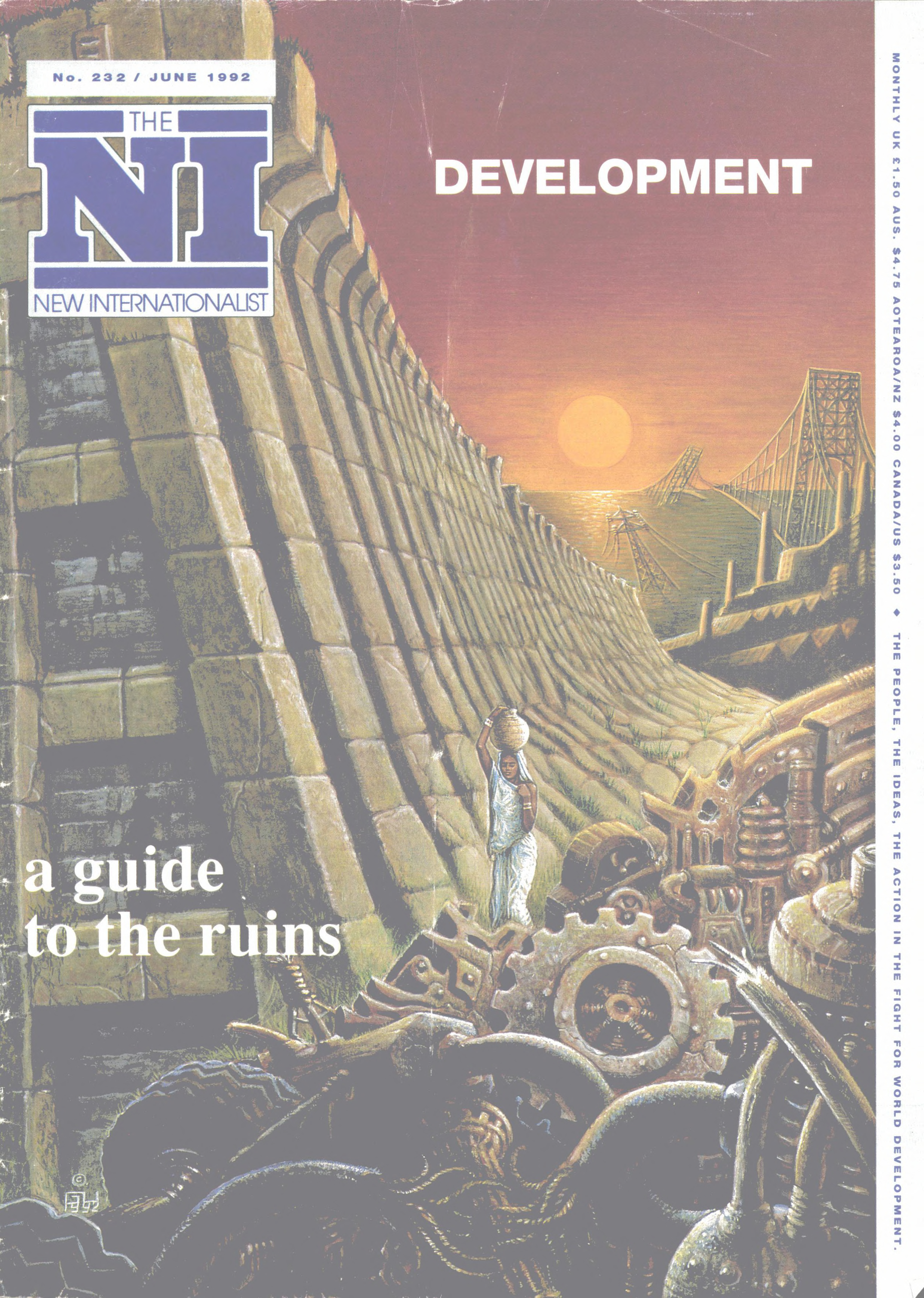

new internationalist

issue 232 - June 1992

SUCCESS!

![]()

The big idea of global development may be in doubt. But don't despair.

Here we focus on four of the many ordinary people who have

taken the initiative, rejecting the parts of the traditional development

model that are not appropriate and shaping their own futures.

TSEWANG RIGZIN LAGRUK is President of the Ladakh Ecological Development Group which tries to follow a completely different model of development - one based on the ecological common sense of Ladakh's traditional culture (similar to that of neighbouring Tibet).

'In the last 20 years Ladakh has changed more than in the previous 200. We've seen our children start to reject the old ways. All the outside influences have had a serious effect on the environment and the traditional sense of community.

Nonetheless I think there are signs of hope. It's a strange thing, but the new contact with the West has made us more conscious of the strengths of our old culture - so many people these days feel a renewed pride in being Ladakhi.

Advert

In my group we've had a lot of success with low-level technologies like solar greenhouses which give us green vegetables in the middle of winter. These improve people's standard of living without their leaving the land.

I stopped using chemical fertilizers 10 years ago when I realized they were damaging the land. Recently many farmers have gone back to organic methods - partly because they've seen the chemicals' effects and partly because of our educational work.

When we won the Right Livelihood Award (the Alternative Nobel Prize) in 1984, I went to Stockholm to receive it. What I saw of Sweden and England was very interesting. But overall I'm happy to be a Ladakhi. It's a calmer, quieter place to live. I just hope it stays that way.'

ATO HAILU WOLDEMARIAM is an Ethiopian farmer working with traditional seeds that have been threatened with extinction - the modern 'global' varieties are much more vulnerable to drought. Supported by Canada's Unitarian Service Committee, farmers like Ato have successfully multiplied 56 traditional varieties of wheat.

'We are lucky that we still have the seeds and are able to grow the wheat that our grandparents grew. The new varieties cost a lot to grow because of the fertilizers and pesticides. Our old varieties always produce a reliable harvest. We even succeeded in increasing our harvest by selecting the better seeds for next season's planting.

I still grow the new varieties alongside the old. If I do not have the money to buy the fertilizer or if there is a drought, I can count on the old seed to produce. Other farmers in our village were persuaded to plant only modern varieties and had problems with drought and pests. Now they want to follow me.

Advert

In the beginning I needed to be convinced to join the programme to grow the seed. Now I realize just how valuable the old seeds are.'

KUMIKO GOTO is a member of the Seikatsu club consumer co-operative in Japan which has been described as 'probably the most significant example of Green economic practice in the industrialized world'. The Club distributes 400 products, all produced according to rigorous ecological and social criteria, to 170,000 member families. The word Seikatsu means simply 'life'.

'I joined the Seikatsu Club almost 10 years ago when I came back to Tokyo with my three daughters. In the first few years I found belonging to the Club really helpful. You see, everything was delivered to my house and so I didn't have to go shopping. Then, as my children grew up, I took responsibility for Seikatsu Club activities. First I was receiving all the goods, then I became a leader of the han (the local group), then I started going out to meetings and conferences. So now I feel like I'm helping other people - kind of paying back my debt.

I think joining the Seikatsu Club made me think what we have to do about food, air, water and the natural environment - not in a political or social sense but in the sense of a simple citizen. As a mother, I want to have something good for my babies. So then we have to think about the manufacturer and the distribution system, and we also have to think about the people in the han, our neighbours. I really learned from my daily living about politics and the economy, which I really didn't care so much about before. Politicians and business people don't look at what folk really need in their lives. There should be some way that we can live in a co-operative way and that's what the Seikatsu Club is.

Plus buying through Seikatsu Club is much cheaper!'

VILMA BELTRAN is leader of a group of community-run soup kitchens in the shanty town of Villa El Salvador, in Peru. Villa has been transformed over the last 20 years from desert land into a thriving self-governing and highly democratic community of 300,000 people.

'When I arrived here I was 22. When we came we thought it was going to be like any other shanty town. But we began to have meetings on our block because we were concerned about not having light, water - we had nothing.

I'm proud of living in Villa because, besides the fact that, as everybody knows, it is very well organized, what we have is thanks to the women. Being organized helps us strengthen ourselves against violence. Violence comes at us from all sides, from the Government as well as from Sendero Luminoso [the Maoist guerilla movement which hates the poor to organize independently]. The solidarity helps us to go on.

We co-ordinate to look for ways to make our lives better, like offering a more balanced diet. We're also making a co-ordinated effort against cholera by distributing to all the soup kitchens first-aid kits that include water purification pills.

But the most important thing here at the moment is that so many of our husbands are out of work, and the only solution is the soup kitchen. We don't do it for profit, we do it out of necessity. And the soup kitchen is not, as Sendero says, a cushion for the Government. It's just that right now we can't let ourselves, or our children, starve to death.

I've visited other shanty towns and they also have soup kitchens. But we've achieved more because we're so organized. Villa is an example to other shanty towns now. They've seen what we've achieved and they are copying us.'

This article is from

the June 1992 issue

of New Internationalist.

This article is from

the June 1992 issue

of New Internationalist.

You can access the entire archive of over 500 issues with a digital subscription.

Subscribe today »

Help us produce more like this

Patreon is a platform that enables us to offer more to our readership. With a new podcast, eBooks, tote bags and magazine subscriptions on offer,

as well as early access to video and articles, we’re very excited about our Patreon! If you’re not on board yet then check it out here.

Patreon is a platform that enables us to offer more to our readership. With a new podcast, eBooks, tote bags and magazine subscriptions on offer,

as well as early access to video and articles, we’re very excited about our Patreon! If you’re not on board yet then check it out here.