Fresh audio product

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

April 8, 2021 Jennifer Berkshire, co-author of A Wolf at the Schoolhouse Door, on teachers’ unions and school reopenings • Helen Yaffe on Cuba’s handling of COVID-19 and their impressive vaccine development (Counterpunch article here)

Fresh audio product

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

April 1, 2021 Laleh Khalili, author of Sinews of War and Trade, on the murky side of the shipping business that got lost in the Ever Given coverage • LaDonna Pivetti on subsidizing employment

Ignore corporate whining

Joe Biden is proposing to finance his badly needed infrastructure program by raising corporate taxes. Business mostly likes the infrastructure program—everything works better when the basics aren’t falling apart—but it doesn’t want to pay for it. Nobody likes paying taxes (well, maybe some oddballs do, but to each their own), but over the last few years, Corporate America has been enjoying the lightest tax burden in history. That needs to change.

Graphed below is the effective tax rate—the share of income that’s paid in tax, not the rate that’s on the books, which nobody pays—for nonfinancial corporations, the motor of the economy, based on data from the national income accounts. In 2020, firms paid 16.8% of their profits in taxes, about the same as 2019 and up slightly from 2018’s 15.0%. That rate, as the dotted trendline shows, has been declining steadily for decades, though the Trump tax cuts took it to fresh lows. As recently as 2005–2007, firms were paying almost 30%. In the 1970s, the average tax rate was over 40%; in the 1950s, almost 50%.

Translating those percentages into dollar terms produces some big numbers. If business were paying taxes at 2007 rates, another $162 billion a year would be flowing into the Treasury, enough to cover the $2 trillion pricetag on the infrastructure bill in 12 years. Take corporate taxes back to 1950s rates—not exactly a time when the capitalist class was suffering—and you could pay the entire infrastructure tab in five years.

And these profit figures are based on what companies report to the IRS, adjusted by the Bureau of Economic analysis to compensate for the more egregious tax breaks. It doesn’t account for all the trillions stashed in offshore tax havens.

They’ve got the money. They just don’t want to share.

Fresh audio product

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

March 25, 2021 Güney Isikara on why Turkish president Recep Erdogan is getting even more authoritarian • Keenan Korth on how the left took over the Nevada Democratic party.

Fresh audio product

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

March 18, 2021 Sochie Nnaemeka, director of the New York Working Families Party, on the awfulness of Andrew Cuomo • Susie Bright, the original sexpert, on what the pandemic is doing to our libidos

Fresh audio product

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

March 4, 2021 Nancy MacLean, author of Democracy in Chains and of a chapter cut from that book now published here, on the right’s reaction to Obama and what it portends for Biden • Tom Athanasiou on what the US return to the Paris climate agreement means, and what Biden means for the climate (Nation article here)

Fresh audio product

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

February 25, 2021 Mike Lofgren on the cultural devolution of the right (article here) • Gustavo Gordillo and Brandon Tizol of DSA’s public power campaign on socializing electricity

Strikes plumb the depths

Although there have been plenty of reports of rising labor militancy in the US—teachers’ strikes, tech and delivery app organizing—it’s sadly not showing up in the strike data.

In its annual release, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reports that there were just 7 major “work stoppages” (which include lockouts as well as strikes) in 2020, tied with 2017 for the second-lowest number since 1947, and beaten only by 2009’s 5. What strike action there was, says the BLS, was mainly against state and local government employers (5 of them), not private ones (2).

Here’s a graph of the grim trajectory. Over the period shown, total employment has tripled, meaning that the collective power of these strikes is a fraction of what it once was. If you adjust for employment growth, last year’s 7 would have been just over 2 by 1950’s standard. That year, there were over 400 strikes.

Another measure, known as days of “idleness” (a nice Victorian touch)—the share of total workdays lost to strikes or lockdowns—was immeasurably small: 0.00%, rounded to two decimal points, which is how it’s published. Last year the twelfth in the last twenty that scored a 0.00%; that never happened before 2001.

Presented with these stats, people sometimes point to smaller strikes as where the action is. That’s probably not the case, but numbers are hard to come by. Another agency, the Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service, publishes data on stoppages involving fewer than 1,000 workers, but they’re presented in a very user-hostile format: monthly spreadsheets listing strikes underway that month, with no aggregated summary numbers like the larger-strike data. When I last looked at the data, in 2018, it was telling the same story as larger strikes.

I don’t want to come across as somebody sitting in a comfy desk chair lecturing, Spartacist-style, about what labor should do. US law and business practice have made it very difficult to mount strikes. Bosses and their politicians understand that without the option to withhold labor, workers are nearly powerless, and they’ve mounted innumerable obstacles to walkouts.

But for those of us who think you can’t have a better society without stronger unions, these symptoms are dire. Jane McAlevey’s mentor at 1199 New England, Jerry Brown, says that the strike is labor’s muscle and if you don’t exercise it regularly it atrophies. Strike just for practice, even if you don’t really need to, he says. The strike muscle is looking very atrophied.

Fresh audio product

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

February 18, 2021 Forrest Hylton on Bolsonaro’s Brazil: disease, chaos, and creeping military dictatorship • Luis Feliz Leon on organizing Amazon workers in Alabama (Gainesville article here; Bessemer, here)

Fresh audio product

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

January 28, 2021 Sarah Buehler, a British Columbia-based climate activist, on the Keystone Pipeline and Biden’s climate policy • Chris Maisano, author of this article, on the work of Leo Panitch

Pandemic boosts union density

Union density—the share of employed workers belonging to unions—rose in 2020 for the first time since 2007 and 2008. Before that, you have to go back to 1979 to find another uptick. Those four years are the only increases in density since the modern BLS series begins in 1964.

Sadly, though, the rise wasn’t the result of any organizing victories. Union membership declined by 2.2% last year—but the pandemic drove down employment even more, 6.7%. As a result, density rose from 10.3% to 10.8%, bringing it back to where it was in 2016.

The increase was driven mainly by the public sector. In 2020, 6.3% of private-sector workers were union members, up 0.1 for the year (though still below 2018’s 6.4%). In the public sector, 34.8% of workers were union members, up 1.2 from 2019, and the highest since 2015. Here’s a graph of the full history. Private sector union density peaked in 1953 and has been declining with little interruption since. It’s now about where it was in 1900 (though those pre-BLS stats should be taken with a grain of salt).

Here’s a graph showing the change in total and union employment from 2019 to 2020. Note that while employment was down overall and in the private and public sectors, employment for union members fell less in the private sector and actually rose in the public. There’s an important message here: besides increasing wages, which you can read about in last year’s installment, having a union increases job security.

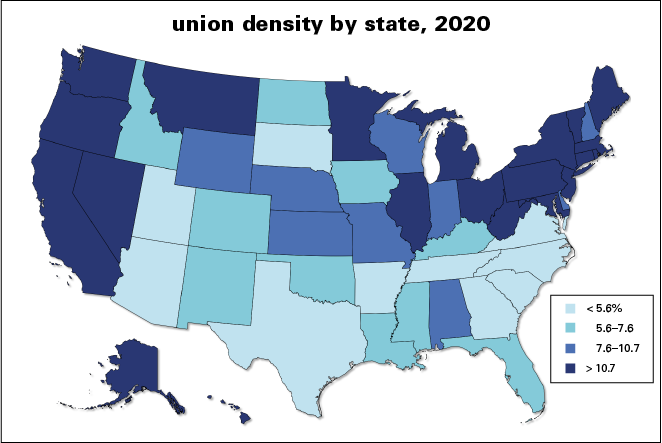

Finally, here’s a map of union density by state. There’s a notable geographic pattern, with unions most present in the Northeast, upper Midwest, and Pacific coast, and weakest in the South and interior West.

As with many things, 2020’s union density figures look to be an artifact of the pandemic. As I said last year:

There are a lot of things wrong with American unions. Most organize poorly, if at all. Politically they function mainly as ATMs and free labor pools for the Democratic party without getting much in return. But there’s no way to end the 40-year war on the US working class without getting union membership up….

And “up” doesn’t mean through COVID-19 quirks.