With our aging population, heath care demands have been increasing, meanwhile the supply of health care simply hasn't been able to keep pace. The most recent data from The Fraser Institute show the seriousness of the situation -- wait times have more-than-doubled since 1993.

Longer wait times impose all sorts of costs on those who are forced to wait to receive health care. These costs include: increased risks of more serious developments (or death), time lost due to queuing in offices and hospitals, time off work, time away from family, time when people are less able to perform household tasks, increased pain and suffering, and I'm sure there are many more, too.

Reducing the explicit costs of gubmnt-provided health care by converting those explicit costs into implicit costs borne by the users is not necessarily efficient. [Addendum: my friend JH points out that it can't possibly be efficient in part because it augments the explicit costs with the addition of all the waiting costs. He also points out that generally speaking, the policy makers don't bear these waiting costs to anywhere near the extent that 'us plain folk' do.].

A number of years ago, I offered this analysis and these suggestions. They are even more important now than they were then. Imagine how much less serious the problem of waiting time would be ten years from now if policy makers had adopted these suggestions when I first made them.

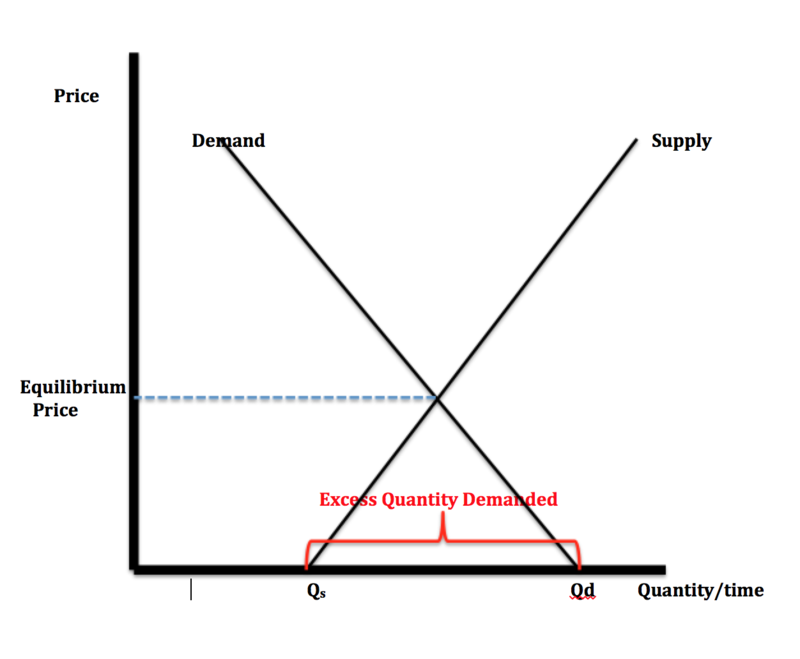

In Canada we have a health care system with devastatingly long wait times for many services. At a zero price, the quantity demanded greatly exceeds the quantity supplied. The standard supply and demand graph illustrating the problem:

Excess quantity demanded at a zero price means the scarce goods and services must be allocated using some other mechanism. As often happens, queuing (waiting) becomes a common allocative mechanism. But people have incentives to try to jump the queue, thus leading to such practices as favouritism, side payments (implicit or otherwise), medical tourism, and death panels (i.e. bureaucratic rules and decisions about who should receive the goods and services).

When I first moved to Canada over 40 years ago, we had a reasonably workable health care system with very short wait periods, despite the gubmnt provision of health insurance. What was different then?

- Canada permitted extra billing. Physicians who wanted to earn more money charged some of their patients more than the fee schedule permitted. But that rarely meant poorer patients were turned away; generally everyone was served.

- Some schmucks got it into their head that the problem with health care costs was too many physicians who were inducing extra demand for their services. That theory was soundly debunked, but it carried the day, and medskool admissions were scaled back. [Digression: a friend once used the supply-induced demand techniques to show that an increase in the number of chickens led to an increase in the demand for eggs.]

- The demography of the physician profession has changed. More men want more time with their families as do the greatly increased number of women who have entered the profession. We get fewer services provided per physician now than we used to.

If these facts are even close to correct, there are several options for reducing wait times.

- Allow physicians and medical service providers in general to charge more than the fee schedule (i.e. bring back extra billing) if they want to. This move would reduce the quantity demanded and increase the quantity supplied of services.

- If people don't like this scheme, worrying about its impact on the poor, alter the insurance scheme as follows:

- Require that every service have a co-pay of 10% up until the patient has paid some amount per year, say $2000, or something like that. It's amazing how having to pay even $10/visit cuts down on the quantity demanded of the services.

- In other words, don't cover everything until patients have paid a good chunk. Make provisions for the needy at the same time, though.

- Such schemes might have been cumbersome 30 years ago, but with computer-billing they would be much easier to implement now.

- Meanwhile, greatly increase the admissions to medskool. Create more physicians. License more practicing nurses. Shift the supply curve outward to the right.

The suggestions I'm offering involve two things:

- Let prices rise very modestly, thus cutting down on the quantity demanded and increasing quantity supplied. The responsiveness of the quantities demanded and supplied to price changes will undoubtedly be small, especially in the short-run, but the longer-run responsiveness is likely to be greater.

- Shift the supply curve to the right.

These two changes are shown here:

Admittedly the above figure is stylized. Nevertheless, the directions of the changes are correct and would greatly help reduce wait times for health care in Canada.

I've written about this before. See this, this, this and this.

Recently the CDHowe Institute pubished studies (see this) about the fiscal glacier (their term) facing Saskatchewan and Alberta (and probably others). These suggestions that I'm offering will not do so much to help with the fiscal glacier. The first one might, but the second one would be costly.

----

Update in 2020: I realize that the major problem with my suggestions will be providing health care for the needy without creating a morass of regulations, information collection, etc. This will not be easy.

More to the point, I would hope for a simple programme even it would mean that some destitute people don't receive high quality health care. Trying to provide a high quality level of health care for everyone is one of the reasons we are imposing waiting costs on everyone. In a world of scarcity, no economy can provide everything for everybody, and trying to provide high quality health care for everyone has given rise to massive waiting times and costs that just aren't being taken into consideration properly.