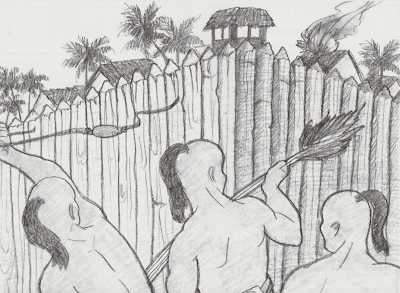

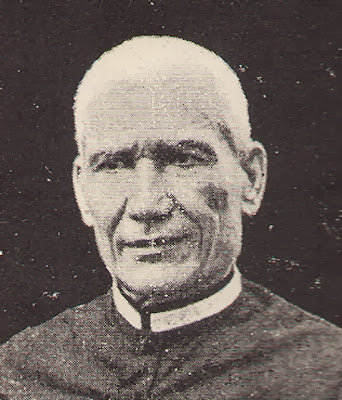

San Vitores

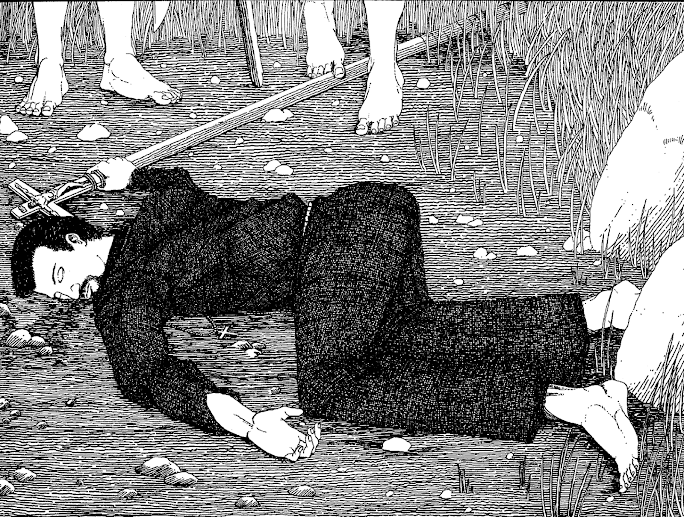

Un diha siempre bai hu fannge' lepblo put i historian i taotao-ta. Esta meggai na kadada na tinige'-hu put este, lao i guinife-hu mohon na un diha bai hu puno' i toru yan na'magåhet este gi un kabåles na lepblo. Lao siempre este na lepblo u matuge' gi Fino' Ingles, ya guaha påtte siha matuge' gi Fino' Chamoru lokke'. Esta gof libiånu para Guahu, para bei estoriåyi taotao nu i hestoria-ta gi Fino' Ingles, lao guaha na biahi debi di bei lachandan maisa para bei cho'gue este lokkue' gi Fino' Chamoru. Put este na motibu-hu guaha na biahi, mañule' yu' påtten hestoria-ta, ya hu ketuge' put guiya gi Fino' Chamoru. Sesso i inayek-hu put este, ti sen interesånte, gi Fino' Ingles "basic" pat gi Fino' i tatan bihu-hu "mata'pang." Put hemplo, a'atan este guini gi sampapa', ni' tinige'-hu put si San Vitores. Ti hu guaiya si San Vitores, ti ya-hu meggai put i hestoria-ña, lao hu tung