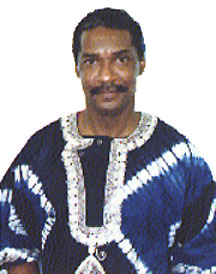

Now 65 years old, Marshall “Eddie” Conway started serving a life sentence for murdering Baltimore police officer Donald Sager when he was 24. Back then, Conway was a postal worker and U.S. Army veteran. He was also a civil rights activist who, as a member of the NAACP and the Congress of Racial Equality, had helped organize efforts to better working conditions for African-Americans at a number of major employers in the Baltimore area. His most renowned role, though, was as Minister of Defense in the Maryland chapter of the Black Panther Party—a position that put him on the front lines of a successful government effort to undermine the party.

Now, Conway is a published author with two books to his credit. In 2009, iAWME Publications issued Conway’s The Greatest Threat: The Black Panther Party and COINTELPRO, in part as a fundraiser for Conway’s legal defense. And earlier this month, AK Press published Conway’s memoir, Marshall Law: The Life and Times of a Baltimore Black Panther, a release party for which takes place April 29 at 2640 Space featuring readings from the book by Bashi Rose and WombWorks Productions, Pam Africa talking about the Mumia Abu-Jamal case, and a performance by Lafayette Gilchrist. (Visit redemmas.org/2640 for more details.)

The new memoir provides an ideal opportunity to consider the man and his life from different perspectives. Edward Ericson Jr. takes a serious look at Conway’s claims to be a political prisoner in his essay about The Greatest Threat. Michael Corbin, who taught at the Metropolitan Transition Center, the former Maryland Penitentiary in Baltimore, places Marshall Law in the American tradition of prison literature. And since decades in prison have tempered Conway’s revolutionary zeal, in a recent phone interview from the Jessup Correctional Institution, he spoke of what hurts and helps the corrective function of prisons, the challenges of fatherhood on the inside, the folly of drug dealing, his own unrealized aspirations in life, and what he would do as a free man.

City Paper: Maryland has a life-means-life policy, essentially denying the possibility for parole for those serving life sentences. It was put in place in 1995 by then governor Parris Glendening, who recently admitted his regrets.

Marshall “Eddie” Conway: Yes, I’m aware of his regrets, 16 years later and after about 50 of my associates are dead. During the course of waiting for this policy to be changed, they passed away.

CP: In your mind, what is wrong with this policy?

MEC: The real problem is that young people coming into the prison system see people that have been participating in the programs, doing all they can to turn their lives around and become usual citizens in the community, and they see how they’ve spent 10, 20, 30, 40 years doing that, with no kind of possibility of release. Well, right away, young guys end up saying, “Well, what’s the point?” It increases the potential for violence, because there is frustration, and it increases hopelessness, which means that people tend to act out. It doesn’t give an incentive for people to rehabilitate themselves, and instead creates negative activity and energy. If you take away hope in a system like this, then you’re going to receive a lot of people returning back to the community very frustrated and hopeless—which is not good, considering the unemployment situation. Also, when a person reaches a certain age, just the fact that a person is, like, 45, 50, or over, means that he becomes a safer risk for release in the community. And most of the time, when you get people that have done an extensive amount of time in prison, they got an associate degree or a bachelor’s degree, so they are more capable of taking care of themselves.

CP: Since the policy has been in place, have you seen an increase in violence, hopelessness, and nihilistic approaches to serving time?

MEC: There was a real spike in violence immediately after that policy was announced. In this institution, for maybe a 10-year period after 1995, pretty much every week there was something fatal or near-fatal occurring. I’m not saying that’s a direct result of Glendening’s policy, but it got so bad that the guards actually refused to come to work. And that violence spread from this institution to others.

CP: If the policy is overturned, would prisons become more suited for rehabilitation?

MEC: Well, of course it would. There are a lot of older prisoners, like myself, working to decrease the level of violence and conflict, and that’s really having a good impact. But in terms of people turning their lives around and having hope and having a desire to motivate change—if you can’t show them something at the end, there’s no incentive for that, and I’m kind of like swimming against the tide. But if they see a way to get out of this predicament—if they work, if they develop, if they grow and change their paradigm—that’s going to probably change the climate within the prison population.

CP: Do you suspect you would have been paroled if this policy hadn’t been in place?

MEC: I don’t know if I would have been paroled, but I have to assume that I would have. I was a model prisoner, quote unquote, meaning that I was—and I am—working to improve the conditions among the prisoners.

CP: Let’s pretend you hadn’t been convicted. What would have been your career?

MEC: I want to believe that, if the community hadn’t been drugged and the jobs hadn’t been shipped overseas, we could have turned this around, and I would have probably ended up teaching somewhere. I had two interests. One was history and education, and the other was the medical profession. I had an aspiration to go into school at Johns Hopkins University, trying to engage in further training for the medical profession. I don’t know that that would have happened, but the teaching probably would have. Either way, I would have been constantly engaging in the community, trying to better the conditions.

CP: What do your sons do?

MEC: I have two sons. One of my sons is an instructor at Bowling Green University in Ohio, teaching computer science. The other is a manager of a water-purification plant in Maryland.

CP: How did you manage as a father in prison?

MEC: Right at the beginning, I have to admit that I succeeded in the case of one and I failed in the case of the other. In the case of my second son, I was estranged from him all the way until he was 18. It was my fault that that was the case, and I certainly never was a father to him. We tried to recover and establish some sort of relationship, and it just didn’t seem to work out. My oldest son, who I knew from the time he was born, I kept in touch with his mother, but I kind of lost track of him through my early years in the prison system simply because, of my initial seven years, I spent six of them in solitary confinement. Somewhere along the line, his mother came to me and just pretty much said, “Look, you need to talk to your son.” So at that time I had organized a 10-week counseling program for young people, and I actually had my son brought to the program. I would sit down and talk to him, one on one, and we would counsel in larger groups. We developed and we started bonding. Like all young black men at the time, he was like, “I’m going to the NBA, going to be a baller.” He was really good, but only so many people get selected to go into the NBA, and he needed to be considering a profession. So he decided to go to college and do the computer-science thing. I’ve supported him as much as I could, and I tried to get him to get his doctorate, but he had had enough of that. I think it was a good experience for both of us.

CP: How do you see it going with other inmates, and their issues with fatherhood?

MEC: It’s one of the things that we deal with a lot. I’ve been working with young guys for the whole entire 40 years, but at some point I had to stop for a while. They were just so angry, and the morals and values had changed to such a degree that I couldn’t be a neutral observer when somebody is talking about beating up their grandmother or disrespecting their mother. But after I started back working with them, I noticed this great hostility to fathers, this great anger at being abandoned.

But the other side of that is that they really want to be very connected and attached to their children, even though they’re locked up. They’re trying to break that cycle, even though the cycle continues due to the simple fact that they are here. They’re trying to be the father that they didn’t have. So that’s good, and it’s more young people like that than not, and a lot of them actually do end up going back out, and they realize that they almost blew that opportunity to be that father. So they tend to get jobs and do what they need to do to stay there because of that.

But, I’m in here now with three generations of people. I’m looking across the generations of absent fathers. And I don’t know how that cycle gets broken if there’s no jobs. One of the great negatives is that maybe 80 percent of people in the prisons around the country are there for drug-related activity, not necessarily violent. Just selling drugs, buying drugs, using drugs, or fighting over drugs, based on the fact that there’s no jobs out there.

CP: It strikes me that these low-level drug dealing jobs are just bad jobs. Low pay, long hours, harsh management.

MEC: You think? And there’s not very good health care!

CP: People tend to think drug dealers get into it because it’s an easy buck.

MEC: It’s not an easy buck. It’s day-to-day survival—and it’s detrimental to your survival. If you manage to make any money, the state comes and scoops up any you might have around, and what you may have stashed away is used for the lawyers. So you end up with nothing.

CP: I wonder, are there any drug dealers out there for whom it doesn’t end badly? The odds are probably better that you’d make it to the NBA.

MEC: This is the bottom line: The nature of drug trafficking itself means that you are going to be highly publicized, that people are going to know who you are, that there’s always going to be a chain of evidence back to you, and that there’s always going to be someone who’s going to want to avoid being incarcerated by saying, “Go look at him or her.” It’s definitely a loser’s proposition.

CP: What do you know about gangs in Maryland prisons?

MEC: The real problem is that anybody in prison that associates with street organizations is pretty much tagged or targeted, be it the Black Guerilla Family, Crips, Bloods, Dead Man Incorporated, or any of them. It has made it impossible to interact in any kind of a positive way with members of those organizations without being tagged. I was educating people, and on the days that I made myself available, I would be in the yard and anybody could approach me to talk about things like how to make parole, how to deal with domestic situations. The result was the prison authorities tagged me. When I talked to the lieutenant about it, I said, “These are the same guys that are going back into our communities, and if they go back in with negative attitudes they are going to be destructive, they’re going to hurt people—your family, my family, everybody else’s families—and I’m not going to ignore that, so I’m going to work with them.”

But you can’t get too close without being labeled, without it being reported that you’re associating with them. So I don’t even go into the yard anymore, but I still work with organizations that provide information, education, insight, and skills to manage conflicts. You get penalized if you try to work with these groups any closer than that. It’s almost as if the prison authorities want them to proliferate, so they can have “X” amount of members or associates documented and get funds for, quote unquote, anti-gang activities. I don’t know what the end is, other than everybody at some point will end up in Big Brother’s files.

CP: What would you do if you were released tomorrow?

MEC: With the rest of my life, I would try to get a house with a nice garden and grow some food and smell the roses. I would still be involved in developing good, positive communities, but I’m a big supporter now of organic food, growing your own food, developing your way to sustain yourself into the future. So I would want to do that and encourage other people to do it.

> Email Van Smith