At two o’clock on June 15th, 1938, a truck pulled-up outside the church hall at St. Mary Magdalene, Hucknall Torkard, England. The vehicle was packed with planks of wood, picks, shovels, crowbars and other assorted tools. The Reverend Canon Thomas Gerrard Barber watched from a side window as a small group of workmen unloaded the vehicle. The driver leaned against the truck smoking a cigarette. His questions to the men removing the tools went unanswered. Barber had ensured all those involved in his plans were pledged to secrecy. No one had thought it possible, but somehow Barber had managed it. This was the day the reverend would oversee the opening of Lord Byron’s coffin situated in a vault beneath the church. Once the men were finished, the driver stubbed his cigarette, returned to his cab, and drove back to the depot in Nottingham.

Over the next two hours, “the Antiquary, the Surveyor, and the Doctor arrived” followed by “the Mason.” It was all rather like the appearance of suspects in a game of Clue. Their arrival was staggered so as not to attract any unwanted attention. Barber was concerned that if the public knew of his intentions there would be an outcry, or at worst a queue around the church longer than the one for his Sunday service.

Near four o’clock, the “workmen” returned. Interesting to note that Barber in his book on the events of this day, Byron and Where He is Buried, used the lower case to name these men rather the capitalization preferred for The Architect, the Mason, and those other professionals. Even in text the working class must be shown their place. Inside the church Barber discussed with the Architect and the Mason the best way to gain access to Byron’s family crypt.

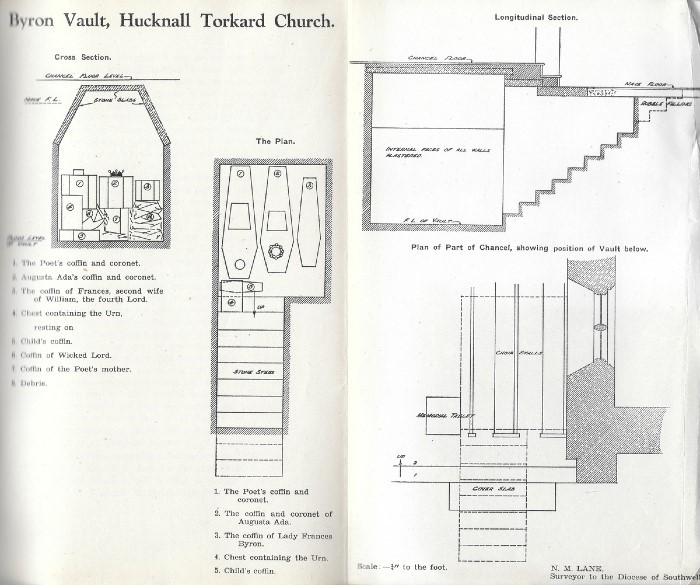

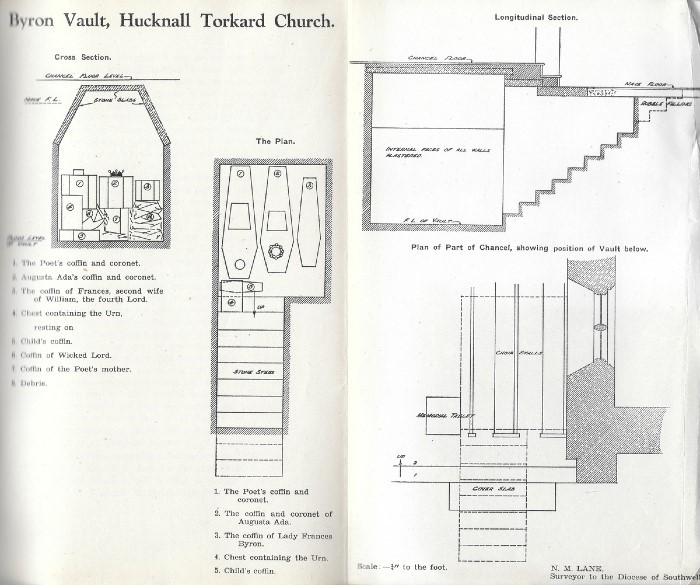

An old print of the interior of the Church shows two large flagstones covering the entrance to the Vault. One of these stones can be seen at the foot of the Chancel steps. It is six feet long, two feet four inches wide, and six inches thick. It was conjectured that the other large stone was covered by the Chancel steps, and that it would be necessary first of all to remove the steps on the south side of the Chancel in order to obtain an entrance to the Vault. Before the work started it was impossible to obtain any information whatever as to the size of the Vault, and to its actual position relatively to the Chancel floor.

Barber was a strange man, an odd mix of contrary passions.. He was as the Fortean Times noted, “a passionate admirer of Byron and a determined controversialist: a dangerous combination, it transpired, in a man placed in charge of the church where the poet had been buried.” For whatever reason, Barber believed he had some connection with the great poet. He never quite made this connection clear but alluded to it like Madame Arcati waffling on about her “vibrations” claiming he had “a personal appointment with Byron.” He was proud the poet had been buried at his church but was deeply concerned that Byron’s body might not actually reside there.

Between 1887 and 1888, there had been restoration work at St. Mary Magdalene “to allow for the addition of transepts.” This meant digging into the foundation. Though promises were made (by the architects and builders) that there would be no damage or alterations to Lord Byron’s vault, Barber feared that this was exactly what had happened. This thought dripped, dripped, dripped, and made Barber anxious about the whereabouts of the dead poet.

Early in 1938, he confided his fears to the church warden A. E. Houldsworth. Barber expressed his intention to examine the Byron vault and “clear up all doubts as to the Poet’s burial place and compile a record of the contents of the vault.”

He wrote to his local Member of Parliament requesting permission from the Home Office to open the crypt. He also wrote to the surviving Lord Byron, who was then Vicar of Thrumpton, asking for his permission to enter the family vault. The vicar gave his agreement and “expressed his fervent hope that great family treasure would be discovered with his ancestors and returned to him.”

At four o’clock, the doors to the church were locked. Inside, around forty (where the fuck did they come from?) invited guests (er…okay….) waited expectantly for the opening of Byron’s vault (what else where they expecting…vespers?). According to notes written by Houldsworth, among those in attendance was one name that Bart Simpson would surely appreciate:

Rev. Canon Barber & his wife

Mr Seymour Cocks MP [lol]

N. M. Lane, diocesan surveyor

Mr Holland Walker

Capt & Mrs McCraith

Dr Llewellyn

Mr & Mrs G. L. Willis (vicar’s warden)

Mr & Mrs c. G. Campbell banker

Mr Claude Bullock, photographer

Mr Geoffrey Johnstone

Mr Jim Bettridge (church fireman)

Of the rest in attendance, Houldsworth hadn’t a Scooby, other than he was surprised that so many had been invited by the good Reverend. As the workmen opened the vault, the guests discussed curtains, mortgages, flower-arranging, and the possibility of war.

At six-thirty, the masons finally removed the slab. A breath of cool, dank air rose into the warm church. Doctor Llewellyn lowered a miner’s safety lamp into the opening to test the air. It was fine. Barber then became (as he described it) “the first to make the descent” into the vault.

His first impression was “one of disappointment.”

It was totally different from what I had imagined. I had seen in my imagination a large sepulchral chamber with shelves inserted in the walls and arranged above one another, and on each shelf a coffin. To find myself in a Vault of the smallest dimensions, and coffins at my feet stacked one upon another with no apparent attempt at arrangement, giving the impression that they had almost been thrown into position, was at first an outrage to my sense of reverence and decency. I descended the steps with very mixed feelings. I could not bring myself to believe that this was the Vault as it had been originally built, nor yet could I could I allow myself to think that the coffins were in their original positions. Had the size of the Vault been reduced and the coffins moved at the time of the 1887-1888 restoration, to allow for the building of the two foot wall on the north of the Vault as an additional support for the Chancel floor?

Pondering these questions, Barber returned to the church. He then invited his guests to retire to the Church House for some tea and refreshments while he considered what to do next. The three workmen were left behind.

With their appetites sated, the Reverend and his guests returned to the church and the freshly opened vault.

From a distant view the two coffins appeared to be in excellent condition. They were each surmounted by a coronet… The coronet on the centre coffin bore six orbs on long stems, but the other coronet had apparently been robbed of the silver orbs which had originally been fixed on short stems close to the rim.

The coffins were covered with purple velvet, now much faded, and some of the handles removed. A closer examination revealed the centre coffin to be that of Byron’s daughter Augusta Ada, Lady Lovelace.

At the foot of the staircase, resting on a child’s lead coffin was a casket which, according to the inscription on the wooden lid and on the casket inside, contained the heart and brains of Lord Noel Byron. The vault also contained six other lead shells all in a considerable state of dissolution–the bottom coffins in the tiers being crushed almost flat by the immense weight above them.

Then Barber noticed that “there were evident signs that the Vault had been disturbed, and the poet’s coffin opened.” He called upon Mr. Claude Bullock to take photographs of the coffin. With the knowledge that someone had opened Byron’s coffin, Barber began to worry about what lay inside.

Someone had deliberately opened the coffin. A horrible fear came over me that souvenirs might have been taken from within the coffin. The idea was revolting, but I could not dismiss it. Had the body itself been removed? Horrible thought!

Eventually after much dithering, Barber opened the casket to find another coffin inside.

Dare I look within? Yes, the world should know the truth—that the body of the great poet was there—or that the coffin was empty. Reverently, very reverently, I raised the lid, and before my eyes there lay the embalmed body of Byron in as perfect a condition as when it was placed in the coffin one hundred and fourteen years ago. His features and hair easily recognisable from the portraits with which I was so familiar. The serene, almost happy expression on his face made a profound impression on me. The feet and ankles were uncovered., and I was able to establish the fact that his lameness had been that of his right foot. But enough—I gently lowered the lid of the coffin—and as I did so, breathed a prayer for the peace of his soul.

His fears were quashed, Barber was happy with what he had done. Basically dug up a grave for reasons of personal vanity. The Reverend Barber does come across as a bit of a pompous git. He was also disingenuous as the one thing he failed to mention about Byron’s corpse was the very attribute that shocked some and titillated others.

Barber was correct someone had already opened Byron’s coffin. But this did not happen during the church’s restoration in 1887-88 but less than an hour prior to his examination of Byron’s corpse. Houldsworth and his hired workmen had entered the crypt while Barber and his pals had tea.

Houldsworth went down into the crypt where he saw that Byron’s coffin was missing its nameplate, brass ornaments, and velvet covering. Though it looked solid it was soft and spongy to the touch. He called upon two workmen (Johnstone and Bettridge) to help raise the lid. Inside was a lead shell. When this was removed, another wooden coffin was visible inside.

After raising this we were able to see Lord Byron’s body which was in an excellent state of preservation. No decomposition had taken place and the head, torso and limbs were quite solid. The only parts skeletonised were the forearms, hands, lower shins, ankles and feet, though his right foot was not seen in the coffin. The hair on his head, body and limbs was intact, though grey. His sexual organ shewed quite abnormal development. There was a hole in his breast and at the back of his head, where his heart and brains had been removed. These are placed in a large urn near the coffin. The manufacture, ornaments and furnishings of the urn is identical with that of the coffin. The sculptured medallion on the church chancel wall is an excellent representation of Lord Byron as he still appeared in 1938.

There was a rumor long shared that Byron lay in his coffin with a humongous erection. This, of course, is just a myth. As Houldsworth later told journalist Byron Rogers of the Sheffield Star newspaper the idea came to the three workmen to open the poet’s coffin when Barber and co. had disappeared for tea:

“We didn’t take too kindly to that,” said Arnold Houldsworth. “I mean, we’d done the work. And Jim Bettridge suddenly says, ‘Let’s have a look on him.’ ‘You can’t do that,’ I says. ‘Just you watch me,’ says Jim. He put his spade in, there was a layer of wood, then one of lead, and I think another one of wood. And there he was, old Byron.”

“Good God, what did he look like?” I said.

“Just like in the portraits. He was bone from the elbows to his hands and from the knees down, but the rest was perfect. Good-looking man putting on a bit of weight, he’d gone bald. He was quite naked, you know,” and then he stopped, listening for something that must have been a clatter of china in the kitchen, where his wife was making tea for us, for he went on very quickly, “Look, I’ve been in the Army, I’ve been in bathhouses, I’ve seen men. But I never saw nothing like him.” He stopped again, and nodding his head, meaningfully, as novelists say, began to tap a spot just above his knee. “He was built like a pony.”

“How many of you take sugar?” said Mrs Houldsworth, coming with the tea.

Whether any of the Reverend Barber’s guests saw Lord Byron’s corpse in the flesh (so to speak) and what they made of it, has never been recorded, other than some of the women felt faint when leaving the crypt, but there may have a light of admiration dancing in their eyes. Barber later returned to the vault on his own at midnight to keep his “personal appointment with Byron” and to most likely to ogle at the size of the great poet’s knob.

Lord Byron—poet, adventurer, rebel, adulterer, and a man hung like a horse.

H/T Flashbak and Fortean Times.