Words & Worlds

By Robert Polito

Among classic American noir novelists from Dashiell Hammett, James Cain, and Kenneth Fearing through Jim Thompson, Patricia Highsmith, and Chester Himes, David Goodis (1917-1967) appears to be the figure always most in need of reclamation, his books drifting out of print, his status shadowy, ever elusive. This predicament proves especially puzzling as his sly, resonant titles – Retreat From Oblivion, Dark Passage, Of Missing Persons, Behold This Woman, Street of the Lost, The Moon in the Gutter, Black Friday, Street of No Return, The Wounded and the Slain, Down There, Fire in the Flesh and Someone Done For – distill into lyric epithets an entire iconic noir cityscape, and sentence-by-sentence, I would argue, Goodis is our most crafty and elegant crime stylist.

Noir is characteristically a language of objects, places, and names, an idiom that in a few bluff words summons worlds. Listen to the opening sentence of Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice: “They threw me off the hay truck about noon.” Thompson’s The Killer Inside Me: “I’d finished my pie and was having a second cup of coffee when I saw him.” William Lindsay Gresham’s Nightmare Alley: “Stan Carlisle stood well back from the entrance of the canvas enclosure, under the blaze of a naked light bulb, and watched the geek.” But noir language just as distinctively proceeds by chipping away at the world and itself until there’s only a vanishing distress signal from a void. Early on in Dark Passage (1946) Goodis advanced a vernacular prose of rococo repeated phrases that limn, then all but erase his characters, here, for instance, mournful Vincent Parry and his disappointed wife Gert:

He began to remember the days of work, the day he had started there, how difficult it was at first, how hard he had tried, how he had taken a correspondence course in statistics shortly after his marriage, hoping he could get a grasp on statistics and ultimately step up to forty-five a week as a statistician. But the correspondence course gave him more questions than answers and finally he had to give it up. He remembered the night he wrote the letter telling them to stop sending the mimeographed sheets. He showed the letter to Gert and she told him he would never get anywhere. She went out that night. He remembered he hoped she would never come back and he was afraid she would never come back because there was something about her that got him at times and he wished there was something about him that got her. He knew there was nothing about him that got her and he wondered why she didn’t pick herself up and walk out once and for all. She was always talking in terms of tall bony men with high cheekbones and hollow cheeks and very tall. He was bony and very thin and he had high cheekbones and hollow cheeks but he wasn’t tall. He was really a miniature of what she really wanted. And because she couldn’t get a permanent hold on the genuine she figured she might as well stay with the miniature.

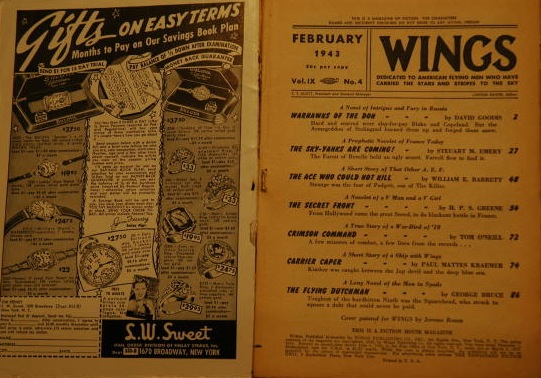

David Goodis wrote under the name Lance Kermit

Goodis would reprise these reiterative, claustrophobic inflections for Down There (1956). But en route, by the time of Street of No Return (1954) and his other Gold Medal and Lion novels of the early 1950s, particularly The Burglar (1953) and Black Friday (1954), he stripped down his echo chamber style into spare, desolate phrases no less wily or confining. Listen now as the three indistinguishable – at first – winos emerge out of Philadelphia’s Tenderloin near the start of Street of No Return:

“We need a drink,” one said. “We need a drink and that’s all there is to it.”

“Well, we won’t get it sitting here.”

“We won’t get it standing up, either,” the first one said. He was middle-aged and tall and very skinny and they called him Bones. He gazed dismally at the empty bottle between his legs and said, “It needs cash, and we got no cash. So it don’t matter whether we sit or stand or move around. The fact remains we got no cash.”

“You made that statement an hour ago,” said the other man who had spoken. “I wish you’d quit making that statement.”

“Well, it’s true.”

“I know it’s true, but I wish you’d quit repeating it. What’s the use of repeating it?”

“If we talk about it long enough,” Bones said, “we might do something about it.”

“We won’t do anything,” the other man said. “We’ll just sit here and get more thirsty.”

Bones frowned. Then he took a deep breath as though he were about to say something important. And then he said, “I wish we had another bottle.”

“I wish to hell you’d shut up,” the other man said. He was a short bulky bald man in his early forties and his name was Phillips. He had lived here on Skid Row for more than twenty years and had the red raw Tenderloin complexion that is unlike any other complexion and stamps the owner as strictly a flophouse resident.

“We gotta get a drink,” Bones said. “We gotta find a way to get a drink.”

“I’m trying to find a way to keep you quiet,” Phillips said. “Maybe if I hit you on the head you’ll be quiet.”

“That’s an idea,” Bones said seriously. “At least if you knock me out I’ll be better off. I won’t know how much I need a drink.” He leaned forward to offer his head as a target. “Go on, Phillips, knock me out.”

Philips turned away from Bones and looked at the third man who sat there along the wall. Phillips said, “You do it, Whitey. You hit him.”

“Whitey wouldn’t do it,” Bones said. “Whitey never hits anybody.”

“You sure about that?” Phillips murmured. He saw that Whitey was not listening to the talk and he spoke to Bones as though Whitey weren’t there.

If Dark Passage and Down There recall, say, Gertrude Stein, Street of No Return suggests Celine, or Beckett. In fact, Goodis’ trio of tramps chatter and wait and go nowhere like exiles from a lost Beckett play with a bottle assuming the role of the slippery Godot. As so often in Goodis, oblique strategies, along the lines of Whitey’s silence here, animate and stagger the narrative. During this same chapter he evokes a full-tilt race riot that Bones, Phillips, and Whitey overhear from some three dark blocks away, but do not see. Or later Whitey listens out of sight on a basement staircase as Gerardo, leader of the Puerto Rican gang around River Street, is pummeled by the “strong-arm specialists” Chop and Bertha, the scene a vivid mash of table talk, blows, howls, and pleas, but absolutely no visual cues about the participants at all.

Goodis at his most cunning is the subtlest of noir novelists, impish and devastating. Although Thompson and Highsmith also devised stealth sentences, their signature astonishments follow from their grand designs: Thompson’s self-consuming narrators, as at the conclusions of A Hell of a Woman and Savage Night, or Highsmith’s recasting of the American-in-Europe theme out of Hawthorne and James for The Talented Mr. Ripley. But Goodis at his most cunning resolutely started small, with the “miniature,” as Parry might say, started with sentences rather than structures, and his wonders inhere in those sentences, as though he always knew words are worlds and, as Bones might say, “that’s all there is to it.”

This essay appeared in the GoodisCON program book.

Robert Polito is the author of Savage Art: A Biography of Jim Thompson, which received the National Book Critics Circle Award in biography, and the editor of the Library of America volumes, Crime Novels: American Noir of the 1930s and 1940s, and Crime Novels: American Noir of the 1950s. One of his current projects, Detours: Seven Noir Lives (forthcoming from Knopf), focuses on David Goodis, along with Weegee, Edgar Ulmer, Sam Fuller, Ida Lupino, Kenneth Fearing, and Clarence Cooper. A longer and somewhat different version of this essay appears as the introduction to the new Millipede Press edition of Street of No Return.

.