Skip to Main Content

Advertisement

Visual Culture

These Photographers Use Staged Portraits to Create Truthful Visions of Black Identity

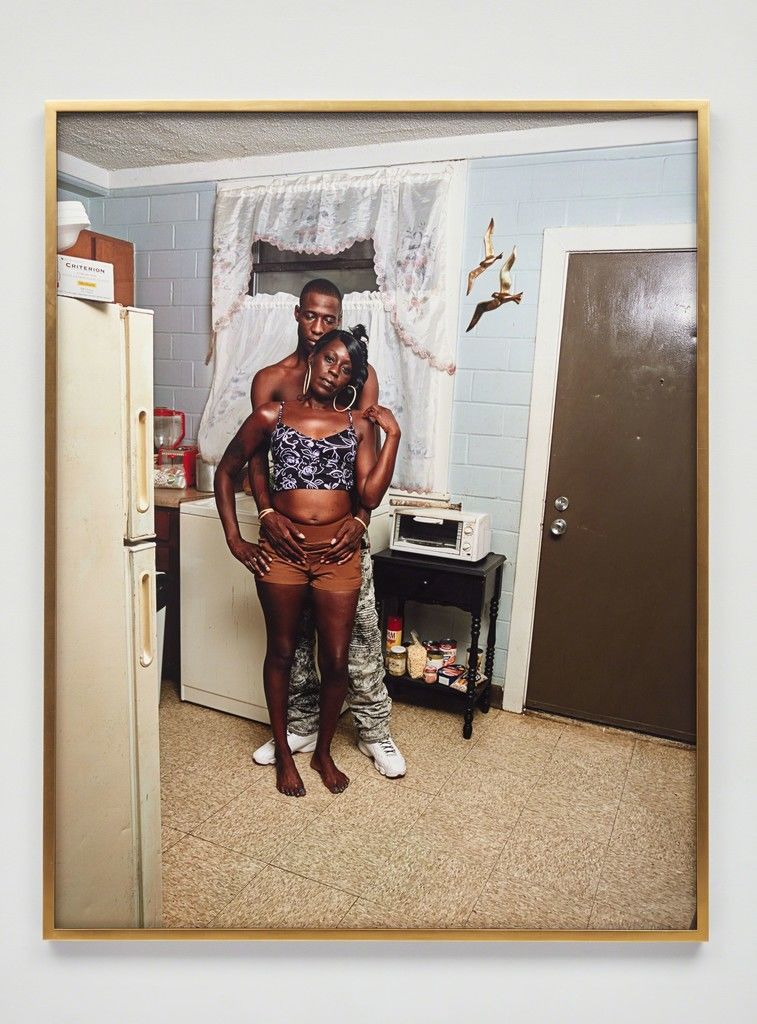

In ’s 2017 photograph Seagulls in Kitchen, a man and woman are standing together in a pose you might find in a framed picture from a high school dance. The walls are a light brick and decorated with two golden seagulls; as the woman stares squarely into the camera, the man closes his eyes. There’s a sensuality present in their embrace, a closeness. Yet despite being photographed as a couple, the pair didn’t know each other prior to working with Lawson. And while the image is steeped in intimacy and emotion, Lawson’s work is not about romanticization. Her portraits, no matter how staged or posed, are meant to emphasize candid moments of Black life.

For centuries, Black and brown people were visualized by everyone except for ourselves. The job of imagemaking was placed in the hands of those interested in constructing and maintaining stringent notions of racialized identity. And while early photographers from the African diaspora aren’t widely known, they’ve always been present. In the United States, 19th-century photographers like J.P. Ball and Augustus Washington opened their own photo studios and were heralded as some of the greatest American photographers of their time. They’re just two of many important photographers from this time, though the majority of their peers’ work was not documented.

Contemporary Black photographers like Lawson are drawing upon and continuing these staged portraiture traditions. , who often works in a documentary format, creates portraits of her family and community that offer sharp commentary on current sociopolitical conditions, and uses staged photographs to look at how images inform the creation of personal identity. In the process, these artists are contributing to a more expansive visual representation of Black life.

Lawson’s forthcoming exhibition “Centropy,” at Kunsthalle Basel (which has been postponed due to COVID-19), continues her practice of telling stories through portraiture. Placing emphasis on domestic settings and the mundane aspects of everyday life, Lawson’s meticulously staged scenes focus on pairs of people and highlight familial and social dynamics. She meets her subjects in everyday places like grocery stores or subway platforms, and she often photographs them in their homes. With “Centropy,” titled after a thermodynamics term, Lawson seems to reference the cultural bond among African diasporic people, who we see in her images.

Advertisement

Isolde Brielmaier, the International Center of Photography’s curator at large, noted that Lawson acknowledges historical photo practices, but she also deviates from some aspects of traditional portrait photography. “She’s very keen and pays close attention to the subjects and how each and every aspect of the subject and their bodies are presented,” Brielmaier said. “She’s taking it a step further. She’s creating these portraits of her sitters within their own spaces, surrounded by their own worlds and with elements that speak to who they are and where they are.”

Distinctive poses and lighting are major components of Lawson’s images. Wanda and Daughters (2009) sees a mother and her two daughters standing against the base of a tree in a massive, woodsy landscape. They’re gently framed by a cluster of lush plants, with the daughters’ heads leaning in towards their mother. The young girls, who appear to be close in age, are clad in jewel-toned jackets with their hair adorned in brilliantly colored beads and barrettes, highlighting the materiality of Black culture that is essential to Lawson’s work. An ordinary exchange between mother and daughters becomes ethereal through Lawson’s lens.

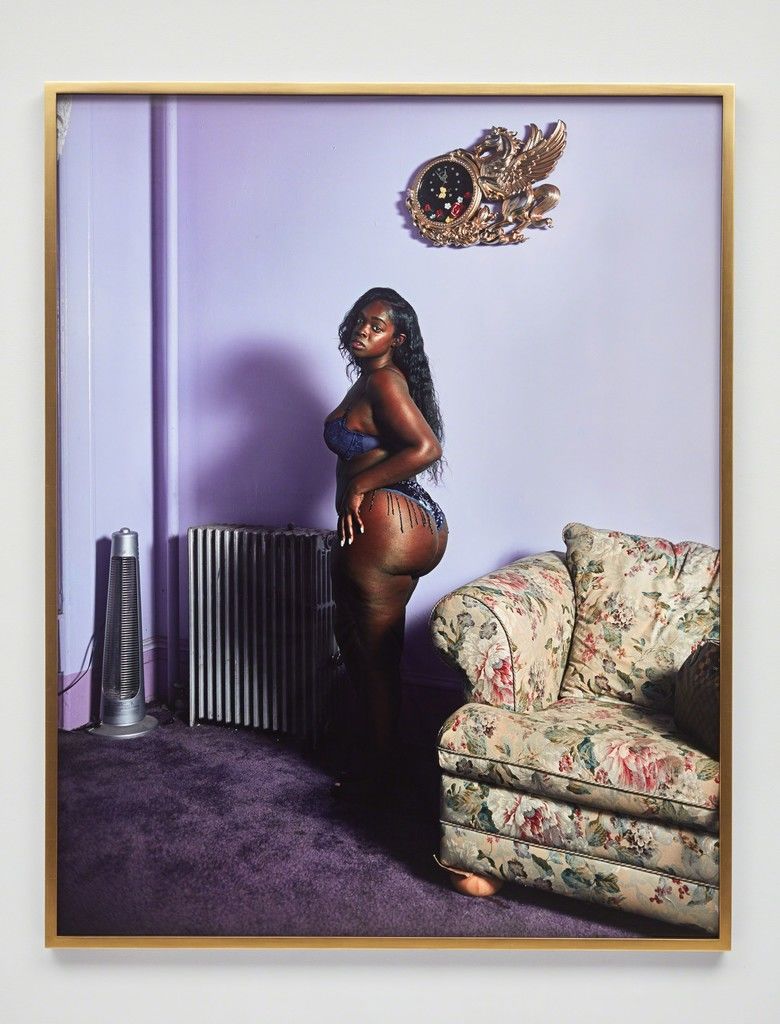

While drastically different from Lawson in her approach, the American artist explores a similar central theme: the body as a conduit for reconstructing Black identities. In her work, Jackson addresses historical representations of the Black body, especially the iconography of Black slaves in the 19th and 20th centuries. Based between Johannesburg, New York, and Paris, Jackson explores conceptions of race in a global context throughout her images. Analyzing the crucial role that photography plays in the construction of identity, Jackson said that she aims to “broaden the map of Blackness” with her work. She uses ornate costumes to visually mark the eras she references, and works with natural lighting to mimic early photographic setups.

For about a decade, Jackson has almost exclusively featured her own body in her photographs. In Labouring under the sign of the future (2017), Jackson photographed herself draped in a thick skirt and petticoat, her body juxtaposed with a stark black background. Her legs are completely hidden by the heavy fabric; the bottom half of the frame is blurred as she jumps and lifts the skirt in a swirl beneath her.Jackson used a blurring effect in many of the images in her traveling solo exhibition “Intimate Justice in the Stolen Moment.”

“‘Intimate Justice’ was born out of a certain amount of frustration—personal and emotional,” Jackson recalled. “A lot of Black Lives Matter things were happening and I felt very weighted and emotionally raw. In a way, I wanted to experience lightness and joy and pleasure.” The collection was also inspired by Jackson’s belief that we need to see more moments of pleasure between Black people in images, both in the present and uncovering those from the past. “What does it mean to perpetually be a slave or a servant? There has to be moments when you’re a lover, when you’re a mother, when you are experiencing your own pleasure,” she said.

Brielmaier echoed Jackson’s motivations around excavating untold Black histories. “I feel like we’re now at a stage as people of color, and especially as art practitioners, creatives, cultural workers, where we can fully embrace and interrogate and explore the nuances and layers that exist when we think of Blackness globally,” Brielmaier said.

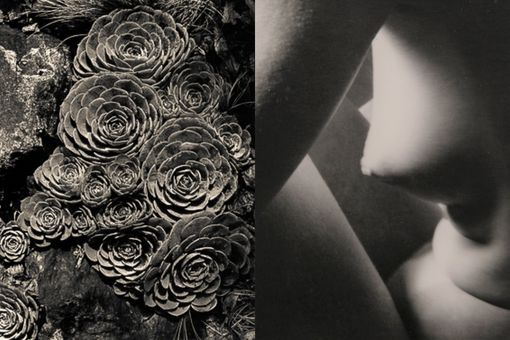

For more than 30 years, has created work that examines the subtleties of lived experience as they relate to race, class, and gender. The artistic giant, who works across photography, installation, and video, addresses themes of power in ways that are relatable. Her current solo exhibition “Over Time,” at Goodman Gallery in Cape Town, offers a survey of several bodies of work that investigate how the past informs the present. Weems is still best known for her iconic “Kitchen Table Series” (1990), a suite of 20 black-and-white images featuring the artist in various staged tableaux around her kitchen table.

“Everybody understands what it means to sit at the kitchen table and to negotiate whatever the issues are in our lives,” Weems explained during a recent interview. The diligently staged-yet-realistic depictions of everyday life—socializing with friends and neighbors, applying makeup, playing with children—analyze the ways that power dynamics impact our relationships, our conversations, and our domestic lives.

Weems noted that so much of her work questions the historically fraught depictions of the Black woman’s body in art. In her 1997 series “Not Manet’s Type”—which references French painter —she observes the relationship between Black subjectivity and modernism, specifically in painting. “How to pose myself becomes a casual way of pulling the audience closer to the subject. I think that is the personhood that exists in the material,” Weems said.

Like that of Jackson, Weems’s oeuvre is filled with self-portraiture. Untitled (man smoking) from Kitchen Table Series (1990)—which set an auction record for Weems just last year—pictures Weems shooting a guileful glance at a man seated across from her at the kitchen table. With a bottle of liquor and a bowl of peanuts between them, the pair are in the middle of a game of cards. Smoke from the man’s lit cigarette floats around them, giving the photograph a hazy, nostalgic appearance. The image feels warm, and instantly transports you to the carefully placed scene.

Though ranging in style, each of these artists understands how deeply perceptions of identity are impacted by images. They look to historical depictions of Black life in photographs and highlight liberating truths about identity—sometimes exciting, and sometimes perfectly ordinary.

There is no singular or monolithic “Black experience,” and the work of these photographers is essential in expressing the abundance of Blackness. No matter the amount of staging, the stories portrayed in these images feel true because they are informed by the experiences of the individuals creating them. As Weems said, “The more you’re specific about who someone is, what they believe, what they think, what they want, what they desire, then you can no longer put them in that one-dimensional box.”

Daria Harper