The following is a transcription of an interview done with me at a Stanford University coffee shop back in the 1980s:

I hope to find a few kindred spirits who opposed the war Were you one of them? If so, I would like to know where you were and what you did. I was one of them. I was at Michigan State University and then just an East Lansing worker from 1967-1975. I attended most all the anti-war demos and helped organizing a few. My orientation wasn't just to end that particular war; but to present a working class critque of capitalism, along with a presentation of what I thought would work better as a society.

First of all, I want to talk about how one joins the antiwar movement. "Join" the antiwar movement... I think that is a very strange term. We didn't have to enlist or enroll or anything. If the antiwar movement wasn't "joined," one merely "became" a part of it as it evolved. Do you agree?

Yes, if you prefer that verb.

How did it happen for you?

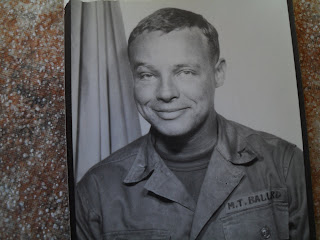

I was in the Marine Corps from 1963 to 1967. Out of high school, I was a patriotic lad, who thought that all the guys had to go in to the military either before or after college. As I knew that one could get money from the government to go to school after one had been "in", I used that knowledge to help me make my decision to enlist. In 1963 there was a universal draft. Also, it didn't hurt that my father had been in the Army as a career before he met an untimely death in the early 50's.

My experience in the USMC led me to a rather vague set of conclusions about the War as it developed. Primary among these was a skeptical reception to major media stories about what it was really like in the War. Although, I never set foot in Vietnam, I did have occasion to "debrief" fellow Marines about their experiences. None of these tales matched what was being written in "Time" magazine, my ideological mentor of choice then. Something was fishy and this nagging concept began to combine with an idea, generated in the bowels of USMC bureaucracy and hierarchy that the War was in reality not about what the major ideological sources claimed--democracy/national liberation--it was instead, a power struggle between States. I was evolving into an undefined sort of pacifist. This was helped along by reading Sartre's triolgy on the roads to freedom--TROUBLE SLEEP, AGE OF REASON, the third's title escapes me now. It was also hastened by meeting a brave young African American, who just refused to take orders and who was thrown in the brig and then out of the USMC. This guy was the one who turned me on to existentialism. I was also beginning to listen to Dylan and the Stones. I was determined not to become, "only a pawn in their game."

Did the madness of the sixties influence your affiliation with the antiwar movement?

Probably, the absurdity of bureaucratic acceptance, combined with the knowledge that we are all, "condemned to be free" i.e. we choose, whether we think so or not. We are responsible.

You said that your later years in USMC were marked by a nagging doubt about what America was doing, and you mentioned "USMC bureaucracy and hierarchy." That reminded me of the distrust we all felt for a monolithic "system." When you looked at the government and "military-industrial complex," did you perceive a giant, insensitive, illogical monolith that was difficult to trust? If not, what did you see?

Well yes. I became more and more convinced that the system was capitalism. As capitalism, the US system was democratic to a degree. The degree that it was democratic, depended largely on what era you were talking about. I saw it as becoming more and more democratic i.e. more and more run by the people; but not run by the people in many important areas, most importantly the economy. The economy was/is related directly to the question of the military industrial complex and those entities influence on the State. While we could elect representitives to the government, those representitives were often more beholden to the minority which made up the employing class and not the majority who made up the employed i.e. what in common terms is called the middle class.

I'm glad we both speak Bob Dylan. Right now, I would like to explore some of the frustration you probably felt about awakening others to the terrible things we were doing in Vietnam, but the public was sleeping soundly underneath all the "ideolgically impregnated/programmed ignorance" you saw around you. Those days reminded me of one of the closing verses of "Desolation Row":

all hail to Nero's Neptune

the Titanic sails at dawn

everybody is shouting,

"which side are you on?"

and Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot

are fighting in the captain's tower

while calypso singers laugh at them

and fishermen hold flowers

between the windows of the sea

where lovely mermaids flow

and nobody has to think too much about Desolation Row.

How frustrated did the "ideolgically impregnated/programmed ignorance" make you and the other protesters around you feel when you tried to make the public aware of what was going on?

Pretty frustrated, indeed. We saw the media manipulation of the issues we brought up because we were bringing these issues up and then we'd see them in the press and it would take an entirely different slant.

No wonder the "ordinary" silent majority was against us. They had been the victims of disinformation. So, we attempted to build a counter culture, complete with its own media. "Music was our only friend--until the end."

Do you remember '68, with the Tet offensive, the assinations of Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King, the Chicago convention and the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia? What did you think of when you watched those events unfold on the news?

Yeah. I remember all of the above. I thought different things about each of the above. I hadn't yet read Marx in '68. By then, I had come to define myself as an anarchist; but I didn't know what exactly I meant by it. I was also contradictory. As I said, I began that year supporting McCarthy and ended it wanting to vote for the Peace and Freedom Party. The assassinations just seemed to stem naturally from a society going bonkers. The Chicago Democratic Convention appalled me. The USSR's invasion of Czechoslovakia didn't come as a surprise; after all there had been Hungary.

Do you think the madness started earlier, perhaps with the civil rights marches? With the JFK assassination?

Maybe.

We discussed your participation in demonstrations, and how the their tenor changed as the war continued:

"And the demonstrations... did they seem more innocent and peaceful in the beginning?

Yes. The participants were more innocent. Those opposing the demonstrations were nastier. They tended to crawl back in to the woodwork as flower power gave way to self-defense classes and steel toed boots.

When did they get nastier? After Chicago in '68? After the Cambodian Invasion in '70? How did they get nastier?

I'd say after Chicago in '68. People knew that they'd better start protecting themselves. At least some people knew. The analysis of the police began to take shape and develop then."

I wonder if you could send some specific anecdotes, do give those who read your remarks a flavor of what antiwar demonstrations were like. Is that possible?

I'll try. There were two types of demo: the planned and the spontaneous. The planned ones took weeks and even months to prepare for--leaflets, posters, publicity in the counter cultural press and so on. Then we we did it on whateve level, local, statewide or national. Most local ones were gatherings of 10 to 20 thousand people which would start in East Lansing and go to the State Capitol building in Lansing. It was a stroll about 5 miles down the main drag, Grand River Avenue. People would be encouraging others to speak some slogan in unison e.g. "One, two, three, four, we don't want your fucking war." or some such thing. Sometimes we would be attacked by onlookers; but most people were sort of tentatively curious, sometimes even supportive. The longer the war went on, the more supportive they got. You would usually be with some of your friends and stick with them throughout the demo. Sometimes you carried signs, sometimes flags. Many people smoked marijuanna and passed joints around. It all went with the counter culture.

At the end of the parade, we'd party. Some would seriously listen to the speeches given by politicians trying to latch on to the popular sentiment or to organizers from mostly lennists sects, who attempted to lead the masses to something or another. Most of us didn't give a damn about the politicians. We wanted the killing to stop, the death culture to die and for enjoyment to take over.

Spontaneous demos, like the one in 1972 over the Christmas bombing of Hanoi, were much more volatile. We ended up taking over the main arteries of the town of East Lansing during it. Without warning, people just started gathering in the streets. People were worried that this action by our government would provoke a nuclear response from the USSR and/or China. Lives were on the line. Serious statements needed to be made and they were. Shutting down business as usual was a form of forced general strike. The cops went crazy, using tear gas on the multitudes and lining the roofs of department stores with men armed with shotguns. But we held our ground. Well, at least for that first and the next night.

When we went out to lunch, you told me about one time when four or five busloads of police came to retake the admin building from a handful of freaks, and how the crowd switched sides from pro-police to pro-freaks when they saw the cops' abuse of powers. Could you please retell that story for the anthology?

Some freaks were arrested for marijuanna possession and/or giving it away in the Michigan State University student union during Spring Term, 1968. Their friends knew that they had been entrapped by the local campus narc police. So, they got pissed and occupied the Administration Building demanding the charges be dropped. The police were bussed in to campus--State Police--to bolster the local cops. There were about three city buses full of them all dressed up in riot gear with ax handle clubs about 5 feet long in their hands. When students on campus got wind that the Admin Bldg was being occupied by long hair freaks they started gathering around jeering the occupiers and waiting for the police to come.

When the cops got there the students outside were totally on the side of the authorities. The cops then lined up very military like on both sides of a 25 yard sidewalk which led from the street and their waiting three buses to the door of the Admin Bldg. A flying squad of helmeted cops was sent in to flush out the freaks.

Students stood outside, waiting for the action and they got it. The freaks were driven out the door and on to the sidewalk where they were pummled by the cops as they were forced to run the gauntlet. The formerly supportive students on the began making pleas to cease hitting these hippie peaceniks. But the police kept running them out through the gauntlet-- I think there were about ten in all, men and women. They were bloody, screaming pain by the time they got on the buses.

Well all hell broke loose then. The students saw that the cops weren't going to stop beating these people, so they started attacking the cops with stones and fists. The cops at first stood their ground; but then the situation became apparent to them--the hippies with ax handles and some of these "hippies" were students. The police were attacking us! We attacked back with a vengence. It was like an army who had their adversaries on the run. The buses began to move. The drivers tried to steer their way through the growing crowds and they people kept rocking the buses all along the way...

Eventually the buses were able to leave campus and behind them stood thousands of newly radicalized students, who had begun to understand which side they were on what it was telling us about the war in Vietnam.

You also told me about burning your hand on a teargas canister. That implies you must have felt outraged by the powers that be (at least once or twice). Can you share any anecdotes of how you felt at public demonstrations?

See above.

I've got too many and not much more time to tell them now. (I was on my lunch hour from work.)

You also spoke of the tension that existed between protesters and "rednecks." Were "rednecks supporters of the government? Why were protesters so cautious? What kinds of troubles were likely to occur between protesters and "rednecks"? Would they take place in public or in private? Specific examples would be good for giving readers a flavor of the time.

Red necks would beat protestors up. Protestors did not usually fight back on an individual level. If crowds were plowed in to by cars of rednecks, there would be a violent response.

They would happen both in public and private. At that time, having hair which was long was considered an act of anti-war activity. You were a target, if you had long hair.

Now I'm thinking about Abbie Hoffman's "second American revolution." How did you feel about people who wanted to overthrow the government?

I thought we needed more democracy. I think Abbie thought that too.

What do you mean when you said " we needed more democracy"? Was the "second American revolution" revolution founded upon the same rationale that Jefferson expressed in the Declaration of Independence:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. That to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed. That whenever any form of government becomes destructive of those ends, it is the right of the people to alter or to abolish it, and to institute a new government... [emphasis added]

To the best of your knowledge, was that the rationale of the "second American revolution"?

Precisely. However, as I've said above, I believed that democracy had evolved from Jefferson's time. I did think that capitalism had become destructive of those ends and the way I saw/see it is that the employing class is the ruling class and therefore the prime movers of governmental policy in the USA. That is to say, governmental policy is shaped according to the interests of the capitalist class; just as it was in the countries ruled by the dogma of "my country, right or wrong."

You also mentioned an interest in presenting "a working class critque of capitalism, along with a presentation of what I thought would work better as a society." I suppose that presentation evolved over time. When did your presentations first appear?

1969.

How did they change as time passed?

They evolved from a vaguely philosophical Marxist critique, shaped mostly by Raya Dunevaskaya and CLR James to a more well defined prgrammatic approach engendered by reading DeLeon, the Situationists, Luckacs and Marx.

How did the public receive them?

Mostly with confusion, derision and ideolgically impregnated/programmed ignorance.

Were your presentations welcome, or did the public seem threatened?

10% welcome. 80% no opinion. 10% opposition.

I'm thinking about alienation of youth now. Did anyone ever harass you for being a member of the counterculture?

No. But the threat was always there. It was in the air. You didn't want to be anywhere near rednecks and rednecks were almost everywhere.

Were you regarded as a communist?

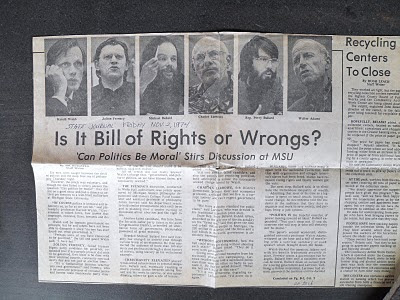

Not a CP member; but I was a known socialist. I ran "against" Congress in 1974 on the Socialist Labor Party ticket.

A traitor?

Few people call ex-Marines traitor.

An anarchist?

I've been called that by both the left and the right.

Did the police ever give you any grief -- drug searches and the like... did you feel alienated from the American culture?

Alienated. For sure. Police are always grief. I was only arrested once for being in a building with 165 other students, who were discussing the Kent State and Jackson State murders. It was May 4,1970. We wern't planning to be arrested, i.e. it wasn't a sit-in. We just continued our teach-in after the building, the Student Union had been officially closed. We didn't want to be arrested; we just wanted to talk.

When Agnew gave his speech about "effete intellectual snobs," how did his remarks make you feel?

Agnews remarks fell like water off a duck's back.

What about Nixon's plea for the "silent majority"? Did their words affect your behavior at subsequent demonstrations?

No.

When I mentioned Agnew's excoriation of protesters and Nixon's call for the silent majority, I recognize their remarks had little affect on you. Do you think they had any affect on the silent majority who came out to contend with you during your demonstrations?

Yes. We were questioning all authority which came from the Establishment. On the other hand, the people who supported the Establishment saw their ideals and dogmas under attack. Being conservative of those dogmas and ideals, they saw Nixon's people as giving voice to their frustrations. Disinformation by the major media plus bourgeois politicians=what democracy we had at that time.

Now I'm thinking about Daniel Ellseburg's Pentagon Papers and the role of the free press. How did you feel when the Papers were published? Maybe betrayed? Maybe a little more cynical about the people in power? Did they affect your behavior at d emonstrations?

No. They didn't affect my behaviour. They only confirmed what I already knew--we needed more democracy, not less.

If you have some other thoughts you would like to share with me regarding the antiwar movement, please do so.

The anti-war movement was essentially divided in to two wings. One wanted to just end this particular war because it was unjust. The other wing wanted to end war by ending the system that produced it. It identified itself as a "counter culture" because in essence, it began seeing itself as beginning to build a new society and consciousness within the womb of the old. The first group went on to become the yuppies. The second group developed in many directions but remained committed to bringing about a more democratic society.