By: Aaron Finestone

DARK PASSAGE

(NY: Messner, 1946; London: Heinemann 1947)

Parry said, “I’m a coward. I don’t like pain.”

“We’re all cowards,” Coley said. “There’s no such thing as courage. There’s only fear. A fear of getting hurt and a fear of dying. That’s why the human race has lasted so long. You won’t have any pain with this. I’m going to freeze your face.

CASSIDY’S GIRL

(NY: Fawcett, 1951; London: Miller, 1958)

The place was a complete wreck. The room looked as if it had been given a vigorous spin and turned upside down several times. The furniture was overturned and the sofa had been sent crashing into a wall with enough force to bring down a lot of plaster and create a gaping hole. A small table was upside down. Two chairs had their legs broken off. Whisky bottles, some of them broken, most of them empty were scattered all over the room. He took a long look at that. Then his eyes leaped. There was blood on the floor.

-----------------

He was trying with all his power to hate the sight of her full fruit-like lips, and the maddening display of her immense breasts, the way they wept out, aimed at him like weapons. He stood looking at this woman to whom he had been married for almost four years, with whom he slept in the same bed every night, but what he saw was not a mate. He saw a harsh and biting and downright unbearable obsession.

----------------------

He walked into the small kitchen and saw more wreckage. The sink was ready to collapse under the weight of empty bottles and filthy dishes. The table was a mess and the floor was worse. He opened the ice box

and saw the sad remains of what he had expected would be his meal tonight.

--------------

The coffee was bubbling. He filled a cup and let the hot black sugarless liquid seep down his throat. It tasted awful. Well, it was not the coffee’s fault.

-------------------

By: Louis Boxer

RETREAT FROM OBLIVION

(Dutton, 1939, Pages 152-153)

While the lights flickered and blazed people were weeping, laughing, screaming and sighing, loving and hating. In a hundred years these people would be gone and the lights would be gone. But there would be new lights and there would be new people. The same story would go on. It had been going on for hundreds of thousands of years.

It was the story told of people in cities, on farms, in hills and in battlefields. They were good, they were bad, they were good again, and before they knew it they had been or what they had done. They might have gone through a lifetime without telling a lie, or they might have existed for twenty-three years and then gone on a killing spree and murdered five women and been electrocuted. It was all over, this show, and someone else was just beginning it some place else.

Everybody passed through it, kings and beggars, rats and elephants. When it was all over there was the body still, with the eyes open or the eyes closed. That didn't matter either. The eyes did not see anything. It was really all over and nothing could be done about it......

There had always been a lot of talk about this Heaven and Hell business. Well, the wise guys could laugh all they wanted to but it wasn't a bad idea. The chances were that it was just that, a lot of talk. But it wasn't a bad idea.Louis Boxer Selection

By: Robert Polito

“What a day, huh?” RP

Dark Passage

(NY: Messner, 1946; London: Heinemann,1947)

They sat there talking about themselves, the things that had once amounted to something in common. Fellsinger’s amateur status with the trumpet. Fellsinger’s refusal to go professional. Fellsinger’s ideas in regard to sincere jazz. Fellsinger’s interest in higher mathematics, and his lack of ability with higher mathematics, and his feeling that if he could make a lot of money in investment securities. Fellsinger’s lack of real ability with anything. Parry’s claim that Fellsinger had real ability with something and as soon as he found that something he would start getting somewhere. Their that something would start getting somewhere. Their vacation at Lake Tahoe a few years back. Fishing at Tahoe and the two girls from Nevada who wanted to learn how to fish. Empty bottles of gin all over cabin. What a wonderful two weeks it had been, and how they agreed that next summer they would be there again at Tahoe. But they weren’t there the next summer because Parry was married that next summer and Gert wanted a honeymoon in Oregon. She wanted to see Crater Lake National Park. She was interested in mineralogy. She collected stones. She claimed there was flame opal to be found in Crater Lake National Park. She liked opal, the flame opal, the white opal with flames of green and orange writhing under the glistening white. She was always asking Parry to get her something in the way of flame opal. He couldn’t afford the flame opal but he got her a stone anyway. He went to a credit jewelry store downtown and said he wanted a flame-opal ring. They said they didn’t have any flame opal in stock but if he came back in a few days they would have something. He didn’t tell Gert about it. He wanted to surprise her. She would have a birthday in four days and he would have the flame opal in three. When he went back to the credit jewelry store they had the flame opal, a fairly large stone set in white gold with a small diamond on each side. They wanted nine hundred dollars. Parry had figured on about four hundred dollars and he was telling himself his only move was to turn and walk out of the store. Then he was thinking the flame opal would make Gert very happy. She hadn’t found any flame opal in Crater Lake National Park. It ruined the honeymoon. She was always saying how badly she wanted a flame opal. Parry made a down payment of three hundred dollars, which reduced his bank account to one hundred dollars. He told them to wrap the ring nicely. He took the ring home and on the following day, which was Gert’s birthday, he presented her with the flame opal. She snatched it out of his hand. She broke a fingernail tearing off the wrapping. Parry was in the room but Gert was all alone in the room with her flame opal and she had a magnifying glass and she studied the stone for twenty minutes. Then when she saw Parry was there she asked him how much he had paid fir the stone. He told her. She asked him where he had bought the stone. He told her. She started to carry on. She said he didn’t have any sense. She said the credit jewelry store was a gyp joint and anybody with half a brain wouldn’t put out nine hundred dollars for a flame opal in a place of that sort. She told him to take the ring back and demand his money. She said the flame opal was full of flaws and the diamonds were chips and the very most the ring was worth tow hundred dollars. She hopped up and down and made a lot of noise. He asked her to quiet down. She threw the ring at him and it hit him in the face and cut his cheek. Gert started to sob and yell at the same time and Parry begged her to quiet down. He said he would take back the ring and try to regain his down payment. She laughed at him. On the following day he took the ring back but they wouldn’t return the down payment. When he became insistent they told him to get a lawyer. He said the ring wasn’t worth nine hundred dollars. They told him to go get a lawyer. He walked out of the store and he was very weary and he knew he was out three hundred dollars. He wanted to go home and tell Gert he had regained the three hundred and put it back in the bank. He knew that wouldn’t work. He had never been much good at putting a lie across. He told himself Gert was right. He didn’t have any sense. He should have used his head and taken her with him when he went to purchase her birthday gift. She was absolutely right. He carried on like that. She wanted him to be something, not a nothing. She wanted him to be something she could respect. He put his hand to the cut on his cheek. She hadn’t meant to do that. She hadn’t meant to hurt him. It was for his own good. Maybe this would be the beginning of change in his life. Maybe from here on he would start to use his head and make something of himself, climb out of the thirty-five-a-week rut in the investment security house. Maybe this was all for the best. He went to the bank and took out fifty of the remaining hundred. He went into a large, dignified jewelry store and asked if they had anything in the way of a flame opal. A man wearing white and black and grey looked Parry up and down and said they didn’t have anything under six hundred dollars. Parry walked out of the store. He went into another store and they didn’t have anything under seven hundred dollars. He went into a third store and a fourth store and a fifth. He was forty minutes past his lunch hour

and he hadn’t eaten yet and he was having a fierce headache. He made up his mind he wouldn’t go back to the office until he had a flame opal for his wife. He went into the sixth store. A seventh and an eighth. The headache was awful. He went into the ninth store and it was a small establishment that seemed sincere, that also seemed as if it was having a hard time staying on its feet. A man well past seventy showed Parry a ring set with a rather small opal, a sterling silver ring setting. The ring looked as if it had been in the store since the store was founded, and the store looked as if [it] had been founded a hundred years ago. But it was a flame opal and Gert wanted a flame opal, and when the man said $97.50 it became a sale. Parry threw a milkshake down his throat and sprinted back to the office. When he arrived at the office the headache was taking his head apart and Wolcott was telling him this sort of thing would never do, and besides his work lately had been anything but satisfactory, and he had better wise up to himself before he found himself out on the street looking for another job. When Parry got home that night he tried to kiss Gert but she turned away from him. He handed her the small package and said happy birthday. She opened the small package and looked at the small flame opal. She looked at it for a while then she let it fall to the floor. She put on her hat and coat. Parry asked her where she was going. She didn’t answer. She walked out of the apartment. Parry heard the door slamming shut. He reached down, picked up the ring. He looked at the closed door, then looked at the flame opal, then looked at the closed door and then looked at the flame opal.

She walked out. He leaned over the newspaper and a few times more he read the Fellsinger story. He heard her going out of the apartment. He went through the newspaper. He tried to get interested in the financial section and gradually he succeeded and he was going through the stock quotations, the Dow-Jones averages, the process on wheat and cotton, the situation in railroads and steel. He saw a small and severely neat advertisement from the firm where he worked as a clerk, where Fellsinger had worked. He began to remember the days of work, the day he started there, how difficult it was at first, how hard he had tried, how he had taken a correspondence course in statistics shortly after his marriage, hoping he could get a grasp on statistics and ultimately step up to forty-five a week as a statistician. But the correspondence course gave him more questions than answers and finally he had to give it up. He remembered the night he wrote the letter telling them to stop sending the mimeographed sheets. He showed the letter to Ger tans she told him he would never get anywhere. She went out that night. He remembered he hoped she would never come back and he was afraid she would never come back because there was something about her that got him at times and he wished there was something about him that got her. He knew there was nothing about him that got her and he wondered why she didn’t pick herself up and walk out once and for all. She was always talking terms of tall bony men with high cheekbones and hollow cheeks and very tall. He was bony and very thin and he had high cheekbones and hollow cheeks but he wasn’t tall. He was really a miniature of what she really wanted. And because she couldn’t get a permanent hold on the genuine she figured she might as well stay with the miniature. That was about as close as he would come to it. She was very thin herself and that was the way he liked them, thin. Very thin. She had practically no front development and nothing in the back but was the way he liked them and the first time he saw her he concentrated on the way she was constructed like a reed and he was interested. He disregarded the eyes that were more colorless than light brown, the hair that was more colorless than pale-brown flannel, the nose that was thin and the mouth that was very thin and the blade-line of her jaw. He disregarded the fact that she was twenty-nine when she married him and the only reason she married him was because he was a miniature of what she really wanted and she hadn’t been able to get what she really wanted. She married him because he came along at a time when she was beginning to worry about it, to worry that she wouldn’t be able to get anything. There were times when she told him the only reason he married her was because he was beginning to worry, because he couldn’t get what he really wanted and he supposed he might as well take this colorless reed while the taking was good, and before years caught up with him and he wouldn’t be able to get anything at all. He said that wasn’t true. He wanted to marry her because she was something he really wanted and if she would only work along with him they would be able to get along and they would find ways to be happy. He tried to make her happy. He thought a child would make her happy. He tried to give her a child and once he got one started hut she went to a doctor and took pills. She said she hated the thought of having a child.

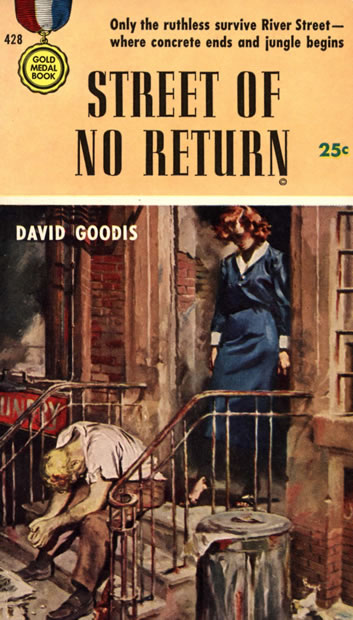

Street of No Return

(NY: Fawcett, 1954; London: Miller,1958;Colorado:Centipede Press, 2007)

[As much as you can of chapter 1 or chapter 6]

The Wounded and the Slain

(NY: Fawcett, 1955; London: Miller, 1959; reprinted by Hard Case Crimes, 2007[chapter 3. especially the end])

Bevan arrived at the door and opened it and stumbled outside. The alley was very dark. It was littered with garbage and tin cans and empty bottles. He stood there blinking and frowning, trying to get his bearings. The thing to do was make it back to Barry Street and find another house where they’d sell him a drink. He mumbled aloud, “Which way is Barry Street?” and then decided it must that faint glow of lamplight filtering through the darkness not very far away. He took a few steps in that direction, tripped over a garbage can, and fell flat. He pulled himself up, stepped past the overturned garbage can, then kicked aside some empty bottles, saying to anyone who cared to listen, “Where’s the street cleaners around here? Why don’t they get to work?”

The reply was a footstep that he didn’t hear, and a moment later it was a blackjack coming toward his skull. But he was a poor target, swaying drunkenly, and the blackjack only grazed his shoulder. He thought it was some night bird flying past, and turned his head to see if another night bird was coming. The lamplight drifting in from Barry Street showed him the black shape of a leather-covered cudgel, above it the black face of the Jamaican. He shrugged and then said, “Come on, take me to a bar. We’ll get a drink.”

The Jamaican worked the blackjack in a sideward arc aimed at Bevan’s temple. Bevan’s arm came up instinctively and he took the impact just below his elbow. The Jamaican became impatient and made another try. Again Bevan took it on his forearm, the force of it going through his arm and against his ribs and sending him sideways going down. He landed on his hip, looked up and saw the Jamaican’s eyes telling him this was for real, and told himself he had to do something, he couldn’t just sit there and take it.

As the blackjack came down again, he rolled away, then rolled back so that his weight came in hard against the Jamaican’s legs. The Jamaican went down but came up fast, still holding onto the blackjack. Bevan glanced around, saw an empty bottle nearby, reached out, and grabbed it. In that instant the Jamaican was closing in and swinging the blackjack. Bevan raised the bottle, using it for a shield. The blackjack hit the bottle, cracking it along the side near the bottom. In Bevan’s hand the broken bottle gleamed with a sudden importance that caused the Jamaican to hesitate. But he came lunging in again, his right hand swinging the cudgel and his left hand shooting out to get inside of Bevan’s jacket. He was trying to do two things at once and it fouled him up; The blackjack missed and his left hand swept past Bevan’s shoulder. The impetus of his lunge ended his life. The cutting edge of the broken bottle sliced his throat and split his jugular vein. All he could do was make a few gurgling sounds, and then he was finished.

Bevan lifted himself to his feet. He looked down at the motionless body. It was resting face down. He said, “You all right?” For some moments he stood there waiting for an answer. Then somehow he knew there’d be no answer. But even so, he told himself, you’d better have a

look and make sure. He leaned over and turned the body on its back. And then he was staring at the bulging unblinking eyes that stared back at him and said, Look what you did. Look what you did to me.

He moved away from the corpse, headed blindly toward any place at all that would get him far away from here. He went down the alley away from Barry Street, through another alley, and then another. And finally he found himself on Harbour Street. In the distance he could see the lighted windows of the Laurel Rock Hotel.

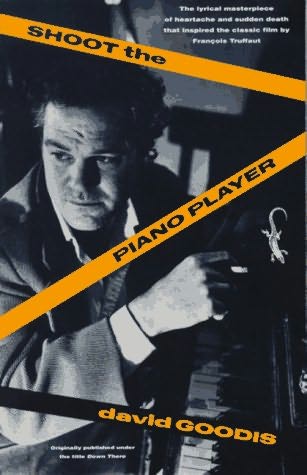

Down There

(Greenwich, Conn: Fawcett, 1956; London: Fawcett, 1958); Republished as SHOOT THE PIANO PLAYER (NY: Grove Press, 1962)

The concert manager walked out of the room. The pianist sat bent over, his face cupped in his hands. He stayed that way for some moments. Then he straightened abruptly and got to his feet. He was breathing hard.

He went out of the room, down the hall toward the stairway. Their suite was on the seventh floor. He went up the three flights with a speed that had him breathless as he entered the living room.

He called her name. There was no answer. He crossed the parlor to the bedroom door. He tried it, and it was open.

She was sitting on the edge of the bed, wearing a robe. In her was a magazine. It was open but she wasn’t looking at it. She was looking at the wall.

“Teresa-“

She went on looking at the wall.

He moved toward her. He said, “Get dressed.”

“What for?”

“The party,” he said. “I want you at the party.”

She shook her head.

“Teresa, listen –“

“Please go,” she said. She was still looking at the wall. She raised a hand and gestured toward the door, “Go-“.

“No,” he said. “Not this time.”

Then she looked at him. “What?” Her eyes were dull.

“What did you say?”

“I said not this time. This time we talk it over. We find out what it’s all about.”

“There is nothing-“

“Stop that,” he cut in. He moved closer to her. “I’ve had enough of that. The least you could do is tell me-“

“Why you shout? You never shout at me. Why you shout now?”

“I’m sorry.” He spoke in a heavy whisper. “I didn’t mean to – “

“Is all right.” She smiled at him. “You have right to shout. You have much right.”

“Don’t say that.” He was turning away, his head lowered.

He heard her saying, “I make you unhappy, no? Is bad for me to do that. Is something I try not to do, but when it is dark you cannot stop the darkness –“

“What’s that?” He turned stiffly, staring at her. “What did you mean by that?”

“I mean – I mean.” But then she was shaking her head, again looking at the wall. “All the time is darkness. Gets darker. No way to see where to go, what to do.”

She’s trying to tell me something, he thought. She’s trying to so hard, but she can’t tell me. Why can’t she tell me? She said, “I think there is one thing to do. Only one thing.”

He felt coldness in the room.

“I say good-by. I go away –“

“Teresa, please – “

She stood up and moved toward the wall. Then she turned and faced him. She was calm. It was an awful calmness. Her voice was a hollow, toneless semi-whisper as she said, “All right, I tell you –“

“Wait.” He was afraid now.

“Is proper that you should know,” she said, “Is always proper to give the explanation. To make confession.”

“Confession?”

“I did bad thing –“

He winced.

“Was very bad. Was terrible mistake.” And then a certain brightness came into her eyes. “But now you are famous pianist, and for that I am glad.”

This isn’t happening, he told himself. It can’t be happening.

“Yes, for that I am glad I did it,” she said. “To get you the chance you wanted. Was only one way to get you that chance, to put you in Carnegie Hall.”

There was a hissing sound. It was his own breathing.

“Woodling,” she said.

He shut his eyes very tightly.

“Was the same week when he signed you to his contract,” She went on. “Was a few days later. He comes to the coffee shop. But not for coffee. Not for lunch.”

There was another hissing sound. It was louder.

“For business proposition.” she said.

I’ve got to get out of here, he told himself. I can’t listen to this.

“At first, when he tells me, is like a puzzle, too much for me. I ask him what he is talking about, and he looks at me as if to say, You don’t know? You think about it and you will know. So I think about it. That night I get no sleep. Next day he is there again. You know how a spider works? A spider, he is low and careful –“

He couldn’t look at her.

“- like pulling me away from myself. Like the spirit is one thing and the body is another. Was not Teresa who went with him. Was only

Teresa’s body. As if I was not there, really. I was with you, I was taking you to Carnegie Hall.”

And now it was just a record playing, narrator’s voice giving supplementary details. “- in the afternoons. During my time off. He rented a room near the coffee shop. For weeks, in the afternoons, in that room. And then one night you tell me the news, you have signed the paper to play in Carnegie Hall. When he comes next time to the coffee shop he is just another customer. I hand him the menu and he gives the order. And I think to myself, Is ended, I am me again. Yes, now I can be me.[“]

“But you know, it is a curious thing – what you so yesterday is always part of what you are today. From others you try to hide it. For yourself it is no use trying, it is a kind of mirror, always there. So I look, and what do I see? Do I see Teresa? Your Teresa? [“]

“Is no Teresa in the mirror. Is no Teresa anywhere now. Is just a used-up rag, something dirty. And that is why I have not let you touch me. Or even come close. I could not let you come close to this dirt.”

He tried to look at her. He said to himself, Yes, look at her. And go to her. And bow, or kneel. It call for that, it surely does. But –

His eyes aimed at the door, and beyond the door, and there was a fire in his brain. He clenched his teeth, and his hands became stone hammerheads. Every fibre in his body was coiled, braced for the lunge that would take him out of here and down the winding stairway to the fourth-floor suite.

And then, for just a moment, he groped for a segment of control, of discretion. He said to himself, Think now, try to think. If you go out that door she’ll see you going away, she’ll be here alone. You mustn’t leave her here alone.

It didn’t hold him. Nothing could hold him. He moved slowly toward the door.

“Edward-“

But he didn’t hear. All he was a low growl from his own mouth as he opened the door and went out of the bedroom.

Then he was headed across the living room, his arm extended, his fingers clawing at the door leading to the outer hall. In the instant that his fingers touched the door handle, he heard the noise from the bedroom.

It was a mechanical noise. It was the rattling of the chain-pulleys at the sides of the window.

He pivoted and ran across the living room and into the bedroom. She was climbing out. He leaped, and made a grab, but there was nothing to grab. There was just the cold empty air coming in through the wide-open window.

Wish I could be there...Have fun, and let me know how it goes... RP

By: Peter Rozovsky

Black Pudding appears in this anthology

Black Pudding

(Manhunt, December 1953)

He walked out of the room and down the hall and down the stairs. As he went out of the house he could still hear the screaming. On Spruce, walking toward Eleventh, he glanced back and saw a crowd gathering outside the house and then he heard the sound of approaching sirens. He waited there and saw the police-cars stopping in front of the house, the policemen rushing in with drawn guns. Some moments later he heard the shots and he knew that the screaming man was trying to make a getaway. There was more shooting and suddenly there was no sound at all. He knew they’d be carrying two corpses out of the house..

He turned away from what was happening back there, walked along the curb toward the sewer-hole on the corner, took Riker’s gun from his pocket and threw it into the sewer. In the instant that he did it, there was a warm sweet taste in his mouth. He smiled, knowing what it was. Again he could hear Tillie saying, “Revenge is black pudding.”

Tillie, he thought. And the smile stayed on his face as he walked north on Eleventh. He was remembering the feeling he’d had when he’d kissed her. It was the feeling of wanting to take her out of that dark cellar, away from the loneliness and the opium. To carry her upward toward the world where they had such things as clinics, with plastic specialists who repaired scarred faces.

The feeling hit him again and he was anxious to be with Tillie and he walked faster.

By: Stacy Shreffler's

Black Friday

(NY: Lion, 1954)

(Hart on Freida): "He told himself, Don't underestimate the brains of this girl; that head of hers is no empty tool box.".

Night Squad (Greenwich, Conn: Gold Medal/Fawcett, 1961; London: Fawcett, 1962)

"You know what's gonna happen to you? One of these days you're gonna get all mashed up. They'll hafta scrape it up and put it in a sack."

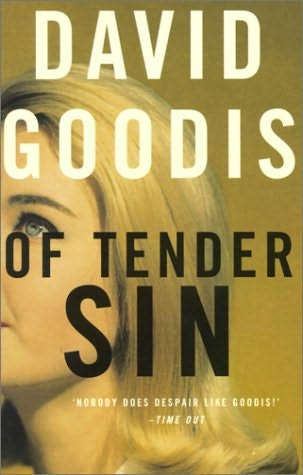

Bonus Cuts: Of Tender Sin (NY: Fawcett, 1952)

"There were too many questions. But all at once they merged and became a single question that had nothing to do with anyone but himself."

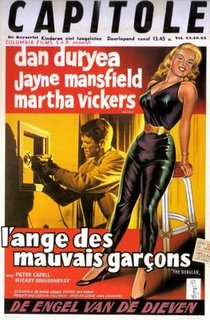

The Burglar (NY: Lion, 1953)

"The only merchandise he ever bought was the definite."

Down There (Greenwich, Conn: Fawcett, 1956; London: Fawcett, 1958); Republished as SHOOT THE PIANO PLAYER (NY: Grove Press, 1962)

"This ain't like thinking with the mind. The mind has nothing to do with it."

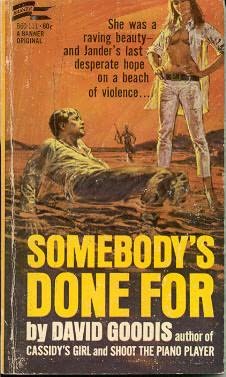

Somebody's Done For (NY: Banner, 1967) "It was as though an invisible wire connected her to him, and somehow the receiver was also the sender." "You're one of those people who keep on hoping even when they know there's hardly any hope, or no hope at all. You just don't know when you're done, do you?"

By: David Schmid

The Moon In The Gutter

(NY: Fawcett, 1953)

'Under the vermilion glory of the evening sun, the vast magnificence of an opal sky, the Vernon Street citizens had no idea of what was up there, they scarcely bothered to glance up and see All they knew was that the sun was still high, and it would be one hell of a hot night. Already the older folks were coming out of shacks and tenements to sit on doorsteps with paper fans and pitchers of water. The families who were lucky enough to have ice in the house were holding chunks of it in their mouths and trying to beat the heat that way. And a few of them, just a very few, were giving nickels to their children, to purchase flavored ice on sticks. The kids shrieked with glee, but their happy sound was drowned in the greater noise, the humming noise that was one big groan and sigh, the noise that came from Vernon throats, yet seemed to come from the street itself. It was as though the street had lungs and the only sounds it could make were the groan and the sigh, the weary acceptance of its fourth-class place in the world. High above it there was a wondrous sky, the fabulous colors in the orbit of the sun, but it just didn't make sense to look up there and develop pretty thoughts and hopes and dreams. The realization came to Kerrigan like the sudden blow of a hammer, putting him down on solid ground where a spade was never anything but a spade. He looked at the torn leather of his work shoes, the calloused flesh of his hands. He thought, You better wise up to yourself and stay out of the clouds.'

The Burglar

(NY: Lion, 1953)

'He saw her. Off to one side, and floating down easily, very gently going down, Gladden had her head lowered on her chest, her arms away

from her body, her gold hair weaving in the green water. He swam down and saw Gladden's arms moving out toward him. It was as though

the arms were reaching toward him. He told himself it was too late, he couldn't do anything for her now. They went down very very deep in

the water and he realized there was no more air in his lungs. He told himself to hurry and kick his way to the surface. But he saw Gladden's

arms reaching toward him, and it was Gladden, it was Gerald's child, and there was only one thing to do, the honorable thing to do. He

went down toward Gladden and got to her and held her and tried hard to lift her and himself up through the water and couldn't do it and

they went down together.'

Street of No Return

(NY: Fawcett,1954; London: Miller,1958; Colorado:Centipede Press, 2007)

'There were three of them sitting on the pavement with their backs against the wall of the flophouse. It was a biting cold night in November and they sat there close together trying to get warm. The wet wind from the river came knifing through the street to cut their faces and get inside their bones, but they didn't seem to mind. They were discussing a problem that had nothing to do with the weather. In their minds it was a serious problem, and as they talked their eyes were solemn and tactical. They were trying to find a method of obtaining some alcohol.'

Down There

(Greenwich, Conn: Fawcett, 1956; London: Fawcett, 1958); Republished as SHOOT THE PIANO PLAYER (NY: Grove Press, 1962)

'There were no street lamps, no lights at all. It was a narrow street in the Port Richmond section of Philadelphia. From the nearby Delaware a cold wind came lancing in, telling alley cats they'd better find a heated cellar. The late November gusts rattled against midnight-darkened windows, and stabbed at the eyes of the fallen man in the street. The man was kneeling near the curb, breathing hard and spitting blood and wondering seriously if his skull was fractured. He'd been running blindly, his head down, so of course he hadn't seen the telephone pole. He'd crashed into it face first, bounced away and hit the cobblestones and wanted to call it a night. But you can't do that, he told himself. You gotta get up and keep running..'

'Now, looking back on it, he saw the wild man of seven years ago, and thought, What it amounted to, you were crazy, I mean really crazy.

Call it horror-crazy. With your fingers, that couldn't touch the keyboard or get anywhere near a keyboard, a set of claws, itching to find the throat of the very dear friend and counselor, that so kind and generous man who took you into Carnegie Hall. But, of course, you knew you mustn't find him. You had to keep away from him, for to catch even a glimpse of him would mean a killing. But the wildness was there, and it needed an outlet. So let's give a vote of thanks to the hooligans, all the thugs and sluggers and roughnecks who were only too happy to accommodate you, to offer you a target.'