Back in 2011, when iPads were still not a familiar sight in our courtrooms, I did a series of posts on using the iPad in legal practice.

Since then, I've presented that information in various formats, and converted it into a PDF ideally suited for use on an iPad, with hyperlinks to recommended apps and websites.

I suggested a couple of months ago posting an updated version, and had a couple of tweets from folks who were interested in that.

So, I've finished revising it, and for those who're interested, here's the latest version. (Just click on the download button to view on your device.)

I think I've removed out-of-date links and apps, but let me know if you find anything odd!

And if you’re in a hurry, these are the main apps I find useful.

quis custodiet ipsos custodes

"Who shall guard the guards?" Juvenal, Satires

Friday, 6 November 2015

Tuesday, 3 November 2015

Watt is a bicycle? Emerson v Police [2015] SASC 161

A few years ago, monkey bikes were quite popular on our roads, and causing headaches for the police and courts trying to decide if they were motor vehicles or not.

A bicycle is defined in the Road Rules dictionary to mean a vehicle with two or more wheels built to be propelled partly or wholly by human power. It includes a power assisted pedal cycle, BUT, does not include a scooter, wheelchair, wheeled recreational device, wheeled toy, or any vehicle with an auxiliary motor capable of generating a power output over 200 watts.

The problem with this is, how can the police, and the courts in turn, know if a device has a motor capable of generating a power output over 200 watts?

As an aside, now that I look at this definition in detail, I wonder, what’s the significance of the reference to an auxiliary motor rather than any motor? “Auxiliary” means something that provides supplementary or additional help or support. A bicycle with pedals and a motor would seem to have an auxiliary motor fitted. But what about a hoverboard, one of these new two-wheeled self-balancing scooters coming out of China in droves? (If you haven't seen one, check out Casey Neistat’s YouTube clip on them.) That is propelled partly by human power — no human equals no movement — but I reckon it’s arguable the motor is not an auxiliary one.

|

| Two-wheeled self-balancing scooter, aka The Hoverboard |

The other part of that definition that is ambiguous is the reference to an auxiliary motor “capable” of generating a power output over 200 watts. Is this restricted to the way the motor is configured at the time of driving, or its theoretical maximum output? What if the motor is “governed” or restricted in some way so that it can’t produce more than 200 watts, even though without that limit it could produce more power?

To come back to the 200 watts point...the South Australian Supreme Court recently considered this issue, in what is I think the first appellate decision dealing with this in Australia.

In Emerson v Police [2015] SASC 161, Ms Emerson was stopped by a police officer on 3 December 2013 while she rode her bicycle fitted with a motor. South Australia has similar provisions to those in Victoria: a power-assisted bicycle, defined as a pedal cycle with auxiliary motors with a power output of no more than 200 watts, is exempt from registration.

(I’m not sure if a power-assisted pedal cycle would fall within the Victorian definition of motor vehicle, because that applies to a vehicle used or intended to be used on a highway and that is built to be propelled by a motor that forms part of the vehicle. That seems to exclude the meaning of bicycle with an auxiliary motor, but I can see some room for argument!)

The police seized the bicycle — although it’s not clear what power they had to do that — and eventually arranged for it to be tested on a device known as a Dynajet around three months later.

That test showed the motor on the bike was then producing about 961 watts of power, and so Ms Emerson was charged with driving an unregistered and uninsured motor vehicle.

She was found guilty of those offences at the Magistrates’ Court, and appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court found there was insufficient evidence in the case to conclude that the Dynajet was properly calibrated, or that it was suitable for measuring low outputs of power-assisted bicycles, when its primary purpose was to measure much greater power outputs of motorcycles. The Magistrates’ Court was also wrong in finding that the Dynajet was a scientific instrument that the common law presumed was accurate in the absence of evidence to the contrary.

Ms Emerson, who was apparently a motor mechanic herself, testified that she modified the power output of the motor with a thing called a “Venturi corrector”. There was, she said, a brass screw on top of the manifold which secured the Venturi corrector, and had a copper wire with a pressed lead seal with “200 watts” stamped on it. The seal was to stop anyone tampering with the corrector after it was set at a 200 watt limit.

Ms Emerson claimed the bike was in pristine condition when the police took it, but the photographs taken (it seems) when it was tested several months later showed it rusted and damaged, with the copper wire and lead seal broken.

Significantly, although this point about the broken seal (and hence possibility of the motor then producing more than 200 watts) was raised at the Magistrates’s Court, the actual bike was not produced and the prosecution witness wasn’t able to comment on it (to the satisfaction of the Supreme Court).

So Ms Emerson succeeded in her appeal.

Although this is mostly one of those turns-on-its-own-facts cases, it does show the importance of ensuring the continuity of exhibits where their condition at the time of the alleged offence is important and there seems to have been some change in their condition by the time of any testing. It also shows the importance of experts properly explaining the methods they use and why those methods are appropriate and relevant to the facts in issue.

It’ll be interesting to see if this is going to become an issue with hover boards. The Metropolitan Police Service has already hit twitter to declare them illegal in London, but I haven’t seen anything similar in Victoria yet.

Own one of these or thinking about getting one? They're illegal to ride in public! Info here: http://t.co/We85yLAzsU pic.twitter.com/vMm0hxNAjs

— MPS Specials (@MPSSpecials) October 11, 2015

What do you reckon?

Wednesday, 7 October 2015

Security, encryption, and keeping confidences confidential

Why is security and encryption important?

Technology has changed the way we access and store information, and the law is one of the industries where iPhones and iPads have become significant tools for day-to-day use. (One recent survey put the rates at 68% and 63% respectively for USA lawyers).

One side effect of the ability to now carry so much computing power and storage with us is that many of us have an awful lot of sensitive and confidential data either in our pocket or in our bags, as well as on our computers, email and cloud-based services.

Thanks to Edward Snowden, we know now that our government and others have been illegally spying on us all for many years, and only now are governments beginning to reign in their security agencies. However, Australia remains one of the most aggressive governments engaging in mass surveillance (although the UK is not far behind), and with the servile acquiescence of the opposition, was able to introduce new laws criminalising disclosure of the existence of certain warrants and authorising bulk metadata collection of all Australians. (Curiously, Malcolm Turnbull, when the Minister for Communications, was the only member of the government to admit the emperor was wearing no clothes when he discussed some ways of easily circumventing this dragnet, including his own admitted use of Wickr, a secure message app.) If you're interested, the Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Amendment (Data Retention) Act 2015 is available here.

Of course, some might say that if you’ve done nothing wrong you’ve got nothing to fear. But surely the point is, if you’ve done nothing wrong, the government has no need to know?

Even if you’re not concerned about the government trawling through all your information, there’s still good reason to want to keep it secure.

For law enforcement and government agencies, it’s self-evident why they should want to keep their data — which is often our data — secure. (Even if it seems they haven’t been entirely successful.)

For the law enforcement and government sector, the Commissioner for Privacy and Data Protection provides some guidance, but most of the detailed policies are internal and not published on the web.

For lawyers, it’s a legal and ethical obligation to keep client confidences confidential, and the law recognises that confidential communications are privileged and so exempt from observation by the executive. So lawyers are both entitled and obliged to take reasonable steps to keep the government from snooping through their confidential data.

Some USA jurisdictions have quite extensive and detailed guidelines for lawyers in this regard, and what constitutes acceptable professional conduct standards when it comes to digital security. Australia seems to have very few explicit policies to guide the legal profession in keeping confidential client data confidential.

The Victorian Legal Services commissioner doesn’t really have anything specific about digital and cloud security in its policies and guidelines. There are general obligations of confidentiality in the Victorian Bar Rules 62–66, the Professional Conduct and Practice Rules 1 and 3, and in the new Legal Profession Uniform Conduct (Barristers) Rules 2015 rules 114–118 and Legal Profession Uniform Law Australian Solicitors’ Conduct Rules 2015 rule 9.

In California a lawyer’s obligation of confidentiality is considered to apply when using WiFi networks. Free public WiFi networks in particular can be a real risk, and if you’re on the same open network as other users — such as at the Supreme Court — your email and cloud-based services could be at risk if you’re not securing your connection with a VPN: see here, here and here.

And only recently, the United Nations’ Special Rapporteur on freedom of expression suggested that encryption is an adjunct of the right to privacy and freedom of opinion and expression. (See here for a good example of the right to privacy applied in 1984 in the UK to stop capricious and gratuitous surveillance.)

Even if you use a password on your computer, anything on your hard drive can be easily accessed by simply removing it from your computer, and either plugging it into an enclosure (just like an external hard drive) or connecting it in another computer. Unless you encrypted your drive, the contents of that disk are then immediately accessible.

The methods of security I’m going to mention do work. (One way of knowing this is just from the hyperbolic response of security agencies that don’t like being prevented from snooping.) For example, the Deputy Attorney-General for the USA declared that a child will die because of Apple’s iOS 8 encryption. And Lavabit and SilentCircle shut down their encrypted email and message services rather than (it seems) hand over their encryption keys to the government. Governments complain about these services because they work.

Metadata

What about metadata? If you rely on Attorney-General George Brandis or former Prime Minister Tony Abbott for your understanding of metadata, then frankly, you’ll have no idea what it is. So, what is it and why is it so important?

At its simplest, metadata is data about data. What that data is depends on what the source data is. The Guardian has a detailed explanation of different types of metadata here.

Photos

For example, with a digital photograph, the associated metadata can be: camera make and model; time and date the image was captured; orientation (landscape or portrait); copyright; flash; exposure time; ISO rating and shutter speed; and GPS coordinates. Don’t think it’s important? The FBI used metadata to track down one of its most-wanted hackers, Higinio O Ochoa III, when he tweeted a photo of his girlfriend’s breasts, but left the GPS data embedded in the EXIF (exchangeable image file) data.

With an email, the metadata might be: to, from, CC and BCC details; date; subject; source IP; received status; message ID; return path; time and date; encryption status; and in-reply-to information. Don’t think it’s important? Former US General and CIA director David Petraeus was discovered having an extramarital affair with his biographer, and accused of providing classified information to her, before pleading guilty to mishandling classified information. His liaison was uncovered by email metadata.

Mobile phones

With mobile phones, the metadata might be: the phone number of every caller; IMEI (international mobile equipment identifier) and IMSI (international mobile subscriber identity) numbers of the handsets and SIM card; call time and duration; and locations of each caller.

Don’t think it’s important? Have a look at:

- the sorts of data retained till very recently by Facebook’s messenger app, which provides similar metadata to mobile phones;

- German politician Malte Spitz metadata records, provided only after he sued his mobile phone company to get the data;

- ABC journalist Will Ockendon’s metadata records.

This is the information that is already provided routinely to law enforcement agencies. Though it’s your data, Australian telcos won’t willingly give all of it to you, though they routinely give it as a matter of course to Australian law enforcement agencies! Journalist Ben Grubb recently won his appeal to the Office of Australian Information Commissioner to gain access to his own metadata, but Telstra is appealing that decision. As a result of that, Telstra has now provided a fee-for-service for limited metadata to its customers.

Another way to collect such information yourself is to install some of the “quantified self” apps available which can record location and activity data, such as Moves, Chronos;or Life360.

Geolocation data

If you have location data turned on in your mobile phone, then you might be creating a metadata history of your regular schedule, showing where and when you can be found.

Search engines and browsers

If you use Google as your search engine, then your search queries, results and pages you visited from those searches are all being captured by Google (and also stored on your hard drive in your internet cache). If you’d rather not have your search history mined for advertising opportunities, or worse, consider a search engine that doesn’t track you, such as DuckDuckGo, or a secure browser such as Tor (on a computer) or Red Onion (on iOS) or Onion Browser (on Android).

Word documents

In a Word document, metadata might show who authored the document, when it was created and what software version was used, and — this is the important bit — embedded comments or previous changes. If you send a Word document to your opponent, do you check it for metadata? As a general rule, never send Word documents to others unless you intend they can see the metadata and edit the contents. Instead, you should routinely use PDF.

For the most part, metadata can’t be prevented, and can’t always be removed or avoided. For example, if you use a mobile phone, unless you turn it off, it will track your location to enable the network to identify which tower your handset should use for receiving calls and data. Likewise, emails will always include header information so the internet can route the message from the sender to the correct recipient. And even if you think you’re clever, and can remove metadata from your computer, you probably can’t. You’d be amazed at the amount of information stored on our computers, and attempts to remove stuff look like …

Understanding when metadata is generated, what type and what risks are associated with it will determine the appropriate response. For example, The Guardian offers a service for the truly worried (or paranoid) called Secure Drop, as does Freedom of the Press Foundation.

Keeping your confidential data confidential

Physically secure and track your devices

Your first layer of security is to restrict physical access to your devices, or to keep track of them.

If you have an Apple computer or device, turn on Find My iPhone under settings > iCloud > Find My iPhone. As long as your device has an internet connection, you can locate it, lock it or wipe it.

Some other options are Prey, Absolute, and FollowMee.

Passwords and data encryption

Turn on password protection on your devices. This will prevent casual or opportunistic access to computers, and for iOS devices, will completely encrypt them when they are secured. (Computer encryption is a must, and I'll discuss that next.)

Choose a strong password (see also the EFF guide to password creation). Don’t choose one of the easy to remember passwords that everyone else chooses. And once you do start using strong passwords, consider an app to store and secure your passwords, so you can create multiple strong passwords, without trying to remember them all. I reckon 1Password is the best, but some folks also like LastPass. (You should also use two-factor authentication where possible with your passwords, either using Authy, or the new feature now available in 1Password. Don’t use the free Google Authenticator: it’s okay, but last year suffered a nasty glitch in one update that wiped all users’ authentication codes till a fix came up, and won’t work across multiple devices unlike the other apps I recommended.)

iOS

On iOS 9, choose Settings > Touch ID and Passcode (or it may be just Passcode). Turn off simple passcode to chose an alphanumeric password, and turn off erase data to prevent a thief from wiping your device, which wipes your Find my iPhone settings or other tracking software.

An incorrect code will result in progressively longer intervals before the device will unlock for a fresh attempt.

When a password is set, iOS automatically encrypts everything on your phone.

Once you do this, you might like Contact Lockscreen, an app that will allow you to display your contact details on the lock screen. It won’t stop opportunistic thieves, but it does allow an honest finder to find you and return your phone, even though it’s locked.

You could consider something like iFortress, but to be honest, I don’t know what that really adds to the encryption built-in to iOS.

Last, if you backup your iOS device on a computer using iTunes, make sure you encrypt those backups too, otherwise, an easy way for an adversary to get around the encryption on your device is to simply access your unencrypted backups which will contain everything your device does up to the point in time you last backed up.

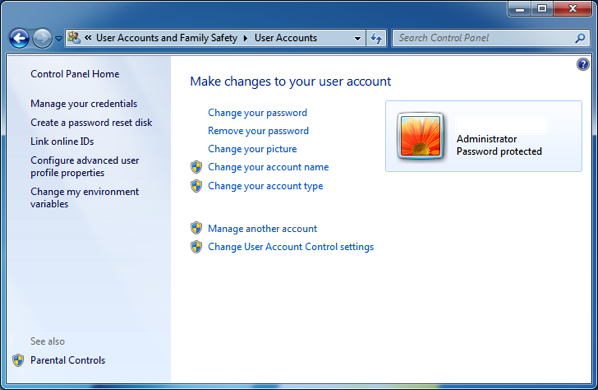

PC (Windows)

In Windows, choose Control Panel > User Accounts and Family Safety > User Accounts. If your computer doesn’t have a password set, chose the option create a password for your account.

Make sure your computer is set to automatically lock when unattended, in Control Panel > Appearance and Personalization > Change screen saver.

Or, if you really want to geek out, try these proximity sensors that lock and unlock your PC: Gatekeeper or Sesame.

Next, turn on full disk encryption. I run Windows in a virtualizer — VMWare to be precise — which allows me to encrypt my virtual Windows machine if I want. (But there’s no real need, given the virtual machine is inside my already-encrypted Mac hard disk.) But my version of Windows doesn’t have BitLocker, Microsoft’s native encryption software, so I can’t show you any screenshots of the setup. The Intercept has a detailed guide for using BitLocker. Otherwise, if you don’t want to spend money purchasing or upgrading to a version of Windows with BitLocker, consider installing the open-source DiskCryptor. Electronic Frontiers Foundation has an excellent how-to guide.

Make sure you encrypt your backups too. Microsoft offers an auto-backup tool called, unsurprisingly, backup. You can then use BitLocker or DiskCryptor to encrypt the backup drive.

Mac

The current version of Mac OS X won’t let you create a user account without a password. Once you have set one up, make sure you require it to log-in to your Mac. Choose System Preferences > Users & Groups and then select your user profile. Click on login options and ensure automatic login is turned off.

You should also make sure that your computer will lock at some stage if you leave it unattended. To do this choose System Preferences > Security & Privacy > General and tick the checkbox next to require password after sleep or screen saver begins.

You can alter sleep or screen saver times in System Preferences > Desktop and Screen Saver.

Or you might prefer a proximity locking app, which will automatically lock and unlock your Mac using your iPhone. Check out MacID, Tether or NearLock.

Next, turn on full disk encryption, called FileVault by Apple. (Actually, this is FileVault 2, and in my experience, works unobtrusively and seamlessly. The original FileVault sucked. I lost access to my hard disk with the original File Vault. Fortunately, I had a backup I could restore from, but it was a major PIA.) You set this in System Preferences > Security & Privacy > FileVault. Turn it on, and set a recovery key. (I recommend against using iCloud recovery, so no one has the recovery key but you, and so no one but you can be compelled to compromise your encryption.)

For more information, check out the detailed guides at The Intercept, and MacWorld.

Last, if you have a backup — you do have a backup, right? — make sure that’s also encrypted. Local backups using Apple’s TimeCapsule are easy enough to encrypt, and backup tools like SuperDuper or CarbonCopyCloner will simply make an exact copy, encryption and all, of the source.

Cloud backups

Most cloud-based services have various degrees of encryption available, but many of those have the encryption key to unlock the data and can be forced to hand over data to law enforcement or security agencies, or even subject to hacking.

For cloud backups where you alone hold the encryption keys, so even the cloud provider cannot see your data even if it wants to, consider Tresorit, Viivo or SpiderOak. These three services also allow for access to encrypted files on iOS and Android devices, although access requires going through their apps and then decrypting onto your device. Viivo in particular is useful because it provides the ability to encrypt files inside DropBox.

Communications encryption

The last step is to protect your communications, especially given our greatest vulnerability to illegal monitoring by various security agencies and also hacking by criminals can occur online.

Virtual private network

The first line of security is to use a virtual private network (VPN). VPNs have a varied reputation, depending on which vested interest you listen to. Like any tool, a VPN can be used for criminal purposes. It can also be used to circumvent geo-blocking (the process music and movie studios use to try to prevent international access to different markets, often in an attempt to artificially inflate local prices.) But for us, it’s use is in securing all our internet communications. Email, web browsing, app traffic, all protected from hacking or interception. Lawyers in particulare should not use public WiFi without using a VPN, unless you’re comfortable putting the security of your device at risk. And anyone who has passwords in their device should want to protect that information from nasties like those I mentioned earlier.

At it’s simplest, a VPN is a secure internet connection between your computer, and another computer, typically a server provided by a VPN provider.

Many commercial VPN providers offer servers in different countries. You can choose which country server to connect to, and all your internet traffic is sent via that server, intermingled with all the other VPN users connected to that server. Here’s an example taken from one VPN provider, tuvpn.com.

Not only does this make your internet connection appear to the wider internet to be coming from a different country, it makes it very difficult to identify your traffic from anyone else who is using the same server. Your host ISP can probably see that you’re connected to a VPN, but because it’s encrypted, can’t see the content of that communication. If the VPN provider keeps logs of your connection, it would be possible for someone to use those logs to identify your connection and the traffic you requested. Some VPNs take the privacy of their clients very seriously, and make a point of not keeping any such logs.

Here’s a brief explanation of VPNs from Google’s privacy team.

For a more detailed discussion of VPNs, check Gizmodo, and for a list of some recommended VPN providers, check out TorrentFreak’s annual review for 2015. I’ve personally used WiTopia, Express VPN and TorGuard and been happy with all. (Yes, TorrentFreak does focus on Bit Torrenting, but BitTorrent can be used to download copyright infringing material, but it can also be used for its original purpose of rapidly downloading large files from multiple peers. The BBC provided an example of this earlier this year when it offered episodes of Dr Who for sale and download via BitTorrent.)

Once you have a VPN, the trick to security is to keep it on when you’re connected to the internet.

There are different tools you can use for this. Both Windows and Mac have built-in software that can connect to a VPN, using two of the three types of VPN connections available: Point to Point Tunnelling Protocol (PPTP) or Layer 2 Tunelling Protocol (L2TP).

On a PC, go to Control Panel and search for VPN.

Choose Setup a virtual private network (VPN) connection.

From this point, the options can change slightly depending on the settings provided by the VPN provider. Most have how-to-guides on their websites.

On the Mac, choose System preferences > Network, select + in the lower-left corner to add a new service and choose VPN from the drop-down menu. Create the new connection, and then fill in the account details from the VPN provider.

In iOS, go to Settings > VPN, then Add VPN configuration, which will take you to second screen below. (If your device has never had a VPN setup before, you’ll need to navigate to Settings > General > VPN for the first time, and then the VPN option will appear in the main settings menu.)

After mucking around with VPNs for a while now, I reckon the best way to use them is to use the OpenVPN app. OpenVPN provides open-source software and so open for the encryption community to ensure there are no backdoors built in to it. (It’s not suitable for all purposes though: I discovered it was useless in China, because China blocks Open VPN ports, and so I had to resort to some other VPN wizadry to circumvent the Great Firewall of China.)

OpenVPN is a bit more complex to install, but is more secure, and (in my experience at least) the only way to reliably keep a persistent active connection. On the Mac, the best software to easily use it (or any VPN for that matter) is Viscosity.

And on an iOS device, the OpenVPN app is the only way to have a persistent VPN connection. All others activated in the setup menu will close when the iPhone or iPad goes into standby or auto-lock. Apple does this deliberately, because a persistent connection will drain your battery more quickly, and will use more data. The average (non-paranoid) user doesn’t require always-on encrypted internet communications, and would probably prefer to use less mobile data and have longer battery life.

Once you download the OpenVPN app, you then have to install the configurations from your VPN provider.

Either you have to (very laboriously) type in the configuration for each server, including the username and password (a bluetooth keyboard helps immensely), or the provider offers downloadable configurations with your username embedded in them, and you copy them across via iTunes. TorGuard used the first way; WiTopia the second. Some VPN providers now also have their own Apps, which do all this for you.

The great thing with the OpenVPN app is that once the connection is turned on, the App will keep it on, even if you move from WiFi to mobile data and back again. The only time I find my VPN drops out is if I lose any internet connection (such as going through an underground rail tunnel) and the authentication times out.

But once you have this installed, all your email, web browsing, and app data is encrypted, and safe from George Brandis’ prying eyes.

Secure web browsing

Where possible, use https — the secure version of hyper text transfer protocol (http) — to view websites. (This is the process most banks use on their sites, which on some browsers will show you a padlock symbol to indicate a secure web connection. EFF has a plug-in for Firefox and Chrome called https everywhere, which automatically turns on https for sites that support it.

And for seriously secure web browsing, use TOR (The Onion Router), or a TOR-compatible iOS browser such as Red Onion (free) or Onion Browser (paid). Tor is slower — much slower — than other web browsers and deliberately won’t run some services such as java and flash. But it is largely impossible to track users on Tor, so when security counts, it’s one of the best options out there. This is probably what Edward Snowden uses when he communicates with the outside world on computer.

You can read about Tor in more detail, but in simple terms it works like this.

There are several options to encrypt email.

The most common is to rely on certificates issued by Certification Authorities like Comodo or Symantec. It is perhaps the easiest to do on Windows, Mac and mobile devices, but typically requires an expensive annual subscription, and relies on the certification authority validating your identity (to be properly effective) and protecting your private keys.

A more complex but open-source option is to rely on PGP (pretty good privacy). Electronic Frontiers Foundation has detailed guides to installing and using PGP, and there’s an iOS app available to provide for PGP emails on iPhones and iPads.

Other alternatives are Enlocked, Virtru and Identillect. They are relatively easy to install and use, and often have plug-ins for Microsoft Outlook if you use that as your email client. Virtue and Identillect allow you to prevent emails from being forwarded. But, they all require you to route your email through their servers, and often require recipients to install the same software in order to receive emails, unlike PGP, which integrates with most mail clients.

Email encryption only works to encrypt the content of the email, but not the header. That means the addressees and subject data remains unencrypted and visible to whoever can gain access to the email.

Voice & messages

Apple’s FaceTime and iMessage provide encrypted communications which (so far) are not known to be subject to real-time interception.

Skype is reputedly capable of interception by the NSA, but is encrypted.

Silent Circle provides strong encrypted voice and message apps, but requires a fairly heft subscription, and offers a USA number only.

Wickr is a good messaging app, and allows the sender to set an auto-destruct on messages. It’s only shortcoming is that it’s not open-source, and so there has been no external verification of its security.

An open-source alternative for both iOS and Android devices is Signal, which offers encrypted voice calling and messaging across both platforms.

Final thoughts

Although security and encryption are often described as a trade-off with convenience, with the exception of email encryption, most of the options I suggested are pretty easy to implement, and will go a long way to keeping your confidential information confidential.

They won’t protect you completely from monitoring and observation: that’s impossible, given the way telecommunications networks operate. For example, a VPN on your mobile phone won’t affect the metadata trial generated as your handset moves from one cell tower to another, disclosing its location to the mobile phone network so it’s possible for the phone to make and receive calls and data.

So too, an internet service provider (ISP) can see if we’re using a VPN, and the amount of data we use. It just doesn’t know the content of that data. But the VPN provider might.

And of course, just as all this encryption and security can keep others from your data, if you lose the keys or passwords needed to gain access to it, you will also be permanently locked out of your data! Make sure your keys and passwords are backed up and accessible in the event your devices fail or are lost, stolen or damaged, and that you have a backup of your data in the event of corruption!

More information

For more info, check:

Freedom of the Press Foundation

Electronic Frontier Foundation surveillance self-defense

The Guardian Project

GPG tools

Tuesday, 30 September 2014

CCOs replace suspended sentences, and more jail now an option

Community Correction Orders can now be imposed along with jail of up to 2 years, and as a substitute where previously suspended sentences of imprisonment might have been imposed.

Parts of the Sentencing Amendment (Emergency Workers) Act 2014 commenced operation yesterday — see SG 330/2014 — including Part 5.

Part 5 amends the Sentencing Act 1991, and answers some of the questions I posed a few weeks back when discussing the abolition of suspended sentences.

It seems the answer to this is now, “Yes!”

A new s 5(4C) provides:

This seems to address the dilemma where the established range for certain offences was jail, even if suspended, and jail was only an option where no other sentence would meet the purposes of sentencing in s 5(2) of the Sentencing Act. It begged the question, how could a court now impose something less than jail? It seems the simply answer is now, “Because the Parliament says so."

Section 44(1) and (1A) of the Sentencing Act now read:

(The reference to Sch 1, cl 5 is to an arson offence.)

The explanatory memorandum points out that the 2-year-jail-plus-CCO option is available where a court fixes a non-parole period, because a court may fix a non-parole period for sentences between 12 and 24 months.

I believe part of the reason the Court of Appeal had not yet delivered any judgment in the possible first-ever guideline judgment, dealing with CCOs as an alternative for offences that would previously have receives suspended jail sentences, was in anticipation of the commencement of these provisions. I’m not certain how they might affect the interpretation of the law as it stood when those sentences were imposed, but my guess is that if the Court of Appeal is going to give a guideline judgment, it wants to say something about the current law as well, so it can provide useful guidance to sentencers for now.

Part 8 of the Justice Legislation Amendment (Confiscation and Other Matters) Bill 2014 proposes further tweaks to the Sentencing Act, which will allow for Magistrates’ Courts to impose CCOs for a cumulative maximum of 5 years in any one case — mirroring the current jurisdictional cumulative cap of 5 years’ jail.

The last sitting day scheduled for Parliament this year is 16 October 2014. Because the election then follows on 29 November, any Bills not passed will lapse, so this amendment may not become law, either this year or perhaps ever. Stay tuned!

Hat-tip to Jono Miller for the good oil on both of these Bills.

Parts of the Sentencing Amendment (Emergency Workers) Act 2014 commenced operation yesterday — see SG 330/2014 — including Part 5.

Part 5 amends the Sentencing Act 1991, and answers some of the questions I posed a few weeks back when discussing the abolition of suspended sentences.

Can CCOs take the place of suspended sentences?

It seems the answer to this is now, “Yes!”

A new s 5(4C) provides:

(4C) A court must not impose a sentence that involves the confinement of the offender unless it considers that the purpose or purposes for which the sentence is imposed cannot be achieved by a community correction order to which one or more of the conditions referred to in sections 48F, 48G, 48H, 48I and 48J are attached.These conditions are, respectively:

- non-association

- residence restriction or exclusion

- place or area restriction or exclusion

- curfew

- alcohol exclusion

(2) Without limiting when a community correction order may be imposed, it may be an appropriate sentence where, before the ability of the court to impose a suspended sentence was abolished, the court may have imposed a sentence of imprisonment and then suspended in whole that sentence of imprisonment.

This seems to address the dilemma where the established range for certain offences was jail, even if suspended, and jail was only an option where no other sentence would meet the purposes of sentencing in s 5(2) of the Sentencing Act. It begged the question, how could a court now impose something less than jail? It seems the simply answer is now, “Because the Parliament says so."

CCOs available in addition to up to 2 years’ jail

Section 44(1) and (1A) of the Sentencing Act now read:

(1) When sentencing an offender in respect of one, or more than one, offence (other than an offence to which clause 5 of Schedule 1 applies), a court may make a community correction order in addition to imposing a sentence of imprisonment only if the sum of all the terms of imprisonment to be served (after deduction of any period of custody that under section 18 is reckoned to be a period of imprisonment or detention already served) is 2 years or less.

(1A) When sentencing an offender in respect of one, or more than one, offence to which clause 5 of Schedule 1 applies, a court may make a community correction order in addition to imposing any sentence of imprisonment.

(The reference to Sch 1, cl 5 is to an arson offence.)

The explanatory memorandum points out that the 2-year-jail-plus-CCO option is available where a court fixes a non-parole period, because a court may fix a non-parole period for sentences between 12 and 24 months.

I believe part of the reason the Court of Appeal had not yet delivered any judgment in the possible first-ever guideline judgment, dealing with CCOs as an alternative for offences that would previously have receives suspended jail sentences, was in anticipation of the commencement of these provisions. I’m not certain how they might affect the interpretation of the law as it stood when those sentences were imposed, but my guess is that if the Court of Appeal is going to give a guideline judgment, it wants to say something about the current law as well, so it can provide useful guidance to sentencers for now.

Further changes?

Part 8 of the Justice Legislation Amendment (Confiscation and Other Matters) Bill 2014 proposes further tweaks to the Sentencing Act, which will allow for Magistrates’ Courts to impose CCOs for a cumulative maximum of 5 years in any one case — mirroring the current jurisdictional cumulative cap of 5 years’ jail.

The last sitting day scheduled for Parliament this year is 16 October 2014. Because the election then follows on 29 November, any Bills not passed will lapse, so this amendment may not become law, either this year or perhaps ever. Stay tuned!

Hat-tip to Jono Miller for the good oil on both of these Bills.

Monday, 1 September 2014

Suspended sentences gone

The last portions of the Sentencing Amendment (Abolition of Suspended Sentences and Other Matters) Act 2013 commenced operation today. Section 2(5) of that Act provides:

The Act repeals Sentencing Act 1991 Part 3, Div 2, subdiv (3). This is the subdivision titled ‘Suspended sentences of imprisonment’, and which contained sections 27 and 29.

There are two relevant transitional provisions to bear in mind.

Section 149C (inserted by s 7 of the amending Act) provides that suspended sentences may still be imposed by higher courts for offences committed before or partly before suspended sentences were abolished in the higher courts from 1 September 2013.

Section 149D (inserted by s 22 of the amending Act) similarly provides suspended sentences may still be imposed by higher courts for offences committed before or partly before suspended sentences were abolished in all courts from 1 September 2014.

I discussed the amending Act back here, when the Bill was first introduced. (The changes were initially slated for 1 December 2013 and 2014, but brought forward when the Act was passed.)

It seems from the second reading speeches and the media announcements at the time that the government wants to restrict the meaning of ‘jail’ to sentences where the offender actually goes into custody.

Any other sentence where the offender walks out the front door of a court house won’t be called ‘jail’.

It’s not entirely clear if sentences that used to receive jail sentences that were then served by suspended sentence or, even earlier, by intensive corrections order now must receive immediate imprisonment, or can still receive another sentence, except that it won’t be labelled ‘jail’.

The Sentencing Advisory Council clearly thinks community corrections orders are a replacement for suspended sentences when a court thinks immediate imprisonment is unnecessary: see its CCO Monitoring Report Feb 2014 and also the Suspended Sentences and Intermediate Sentencing Orders Final Report Part 2 April 2008.

I think that’s consistent with what the Attorney-General said in the second reading speech I discussed in my earlier post.

But it’s not a view universally accepted by the Courts.

Part of the reason is probably because of the Sentencing Act itself, and the Courts doing their best to obey the Sentencing Act.

Section 5 of the Sentencing Act relevantly provides:

And section 27(3) provided:

Turning to my trusty Fox & Freiberg on Sentencing, I see that the Kirby J grappled with this in Dinsdale v The Queen (2000) 202 CLR 321 at [74], [76], [79] – [81].

Once the sentencing range for some offences was established as jail — even though it might sometimes be suspended — it became very difficult to suggest that it now ought not be jail. It seems to me this is the problem that comes about because of the current government’s desire to label only actual jail as jail. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, and seems to be a lot more logical and intellectually honest about what’s happening in the sentencing process. But it suggests that the effect of the change either wasn’t fully appreciated when the changes were made, or the government didn’t mind that it might mean more people go to jail. IMHO, that’s not a good thing. Jail really should be an option of last resort, rather than a default because there’s no other option permitted to the courts because of the way the legislation is structured. (No matter what your philosophical approach might be to jail, if the purpose of it is to stop people reoffending — whether because they are deterred, or rehabilitated — then it seems it’s not so effective. Combine that with the bad side effects of jail, and it’s worth asking if there should be an alternative in appropriate cases.)

I think the government did mean for CCOs to occupy some of the ground previously occupied by ICOs and suspended sentences, but because the legislation doesn’t say that in those precise terms, it’s open to argument.

Presumably, this would mean that a Court would have to consider the maximum sentence available for a CCO — say, 5 years for recklessly causing injury — and conclude that would still be inadequate before it could then go up the sentencing hierarchy to consider a jail sentence. But again, that’s open to argument as well.

It seems that some courts have accepted this might be the case. The Age reported last year that one offender received a 10-year CCO. But that case, and two others, are before the Court of Appeal after the DPP asked for the first ever guideline judgment in Victoria on the scope and limits of CCOs. I understand those cases were argued on 31 Jul and 1 Aug, and the Court has reserved its decision on whether it will give a guideline judgment, and if it does, what that judgment will be.

Hopefully the Court will provide a guideline judgment, because it seems this is an area ripe for such direction. And hopefully it will agree with the view of the Sentencing Advisory Council. With the abolition of suspended sentences, there is a real need for an intermediate sentencing option that allows for serious punishment without all the brutalising effects of jail. There are some offenders who really are terrified just at the thought of being before a Court, and who truly do suffer significant punishment and experience deterrence without being locked up. On the other hand, there are some offenders who do need to be locked up. Ideally, our justice system should allow out courts to adequately deal with both.

(5) If a provision referred to in subsection (4) does not come into operation before 1 September 2014, it comes into operation on that day.The most significant change is the abolition of suspended sentences of imprisonment.

The Act repeals Sentencing Act 1991 Part 3, Div 2, subdiv (3). This is the subdivision titled ‘Suspended sentences of imprisonment’, and which contained sections 27 and 29.

There are two relevant transitional provisions to bear in mind.

Section 149C (inserted by s 7 of the amending Act) provides that suspended sentences may still be imposed by higher courts for offences committed before or partly before suspended sentences were abolished in the higher courts from 1 September 2013.

Section 149D (inserted by s 22 of the amending Act) similarly provides suspended sentences may still be imposed by higher courts for offences committed before or partly before suspended sentences were abolished in all courts from 1 September 2014.

I discussed the amending Act back here, when the Bill was first introduced. (The changes were initially slated for 1 December 2013 and 2014, but brought forward when the Act was passed.)

It seems from the second reading speeches and the media announcements at the time that the government wants to restrict the meaning of ‘jail’ to sentences where the offender actually goes into custody.

Any other sentence where the offender walks out the front door of a court house won’t be called ‘jail’.

It’s not entirely clear if sentences that used to receive jail sentences that were then served by suspended sentence or, even earlier, by intensive corrections order now must receive immediate imprisonment, or can still receive another sentence, except that it won’t be labelled ‘jail’.

The Sentencing Advisory Council clearly thinks community corrections orders are a replacement for suspended sentences when a court thinks immediate imprisonment is unnecessary: see its CCO Monitoring Report Feb 2014 and also the Suspended Sentences and Intermediate Sentencing Orders Final Report Part 2 April 2008.

I think that’s consistent with what the Attorney-General said in the second reading speech I discussed in my earlier post.

But it’s not a view universally accepted by the Courts.

Part of the reason is probably because of the Sentencing Act itself, and the Courts doing their best to obey the Sentencing Act.

Section 5 of the Sentencing Act relevantly provides:

(3) A court must not impose a sentence that is more severe than that which is necessary to achieve the purpose or purposes for which the sentence is imposed.

(4) A court must not impose a sentence that involves the confinement of the offender unless it considers that the purpose or purposes for which the sentence is imposed cannot be achieved by a sentence that does not involve the confinement of the offender.The now-repealed s 27(1) used to provide (before the 2013 amendments commenced):

(1) On sentencing an offender to a term of imprisonment a court may make an order suspending, for a period specified by the court, the whole or a part of the sentence if it is satisfied that it is desirable to do so in the circumstances.Section 27(1A) then listed the criteria for determining if a suspended sentence was appropriate.

And section 27(3) provided:

(3) A court must not impose a suspended sentence of imprisonment unless the sentence of imprisonment, if unsuspended, would be appropriate in the circumstances having regard to the provisions of this Act.These provisions produced the odd result that a Court had to conclude that nothing other than jail would achieve the purposes of sentencing necessary in the case, and yet, it was appropriate to not send the offender to jail.

Turning to my trusty Fox & Freiberg on Sentencing, I see that the Kirby J grappled with this in Dinsdale v The Queen (2000) 202 CLR 321 at [74], [76], [79] – [81].

[74] The statutory power to suspend the operation of a sentence of imprisonment, although historically of long standing, is sometimes considered controversial. The “[c]onceptual [i]ncongruity” involved in this form of sentence has been criticised. It has been suggested that there is a temptation to use this option where a non-custodial order would have been sufficient and appropriate. It has also been suggested that, despite the rhetoric, such sentences are seen by some not to constitute much punishment at all.

[76] Whatever the theoretical and practical objections, suspended imprisonment is both a popular and much used sentencing option in Australia. Courts may not ignore the provision of this option because of defects occasionally involved in its use. Nonetheless, the criticisms draw attention to the need for courts to attend to the precise terms in which the option of suspended sentences of imprisonment is afforded to them and to avoid any temptation to misapply the option where a non-custodial sentence would suffice. They also emphasise the need to keep separate the two components of such a sentence, namely the imposition of a term of imprisonment, and the suspension of it where that is legally and factually justified.

[79] The common failure of Parliaments to state expressly the criteria for the suspension of a term of imprisonment has led to attempts by the courts to explain the considerations to which weight should be given and the approach that should be adopted. The starting point … is the need to recognise that two distinct steps are involved. The first is the primary determination that a sentence of imprisonment, and not some lesser sentence, is called for. The second is the determination that such term of imprisonment should be suspended for a period set by the court. The two steps should not be elided. Unless the first is taken, the second does not arise. It follows that imposition of a suspended term of imprisonment should not be imposed as a “soft option” when the court with the responsibility of sentencing is “not quite certain what to do”.

[80] The question of what factors will determine whether a suspended sentence will be imposed, once it is decided that a term of imprisonment is appropriate, is presented starkly because, in cases where the suspended sentence is served completely, without reoffending, the result will be that the offender incurs no custodial punishment, indeed no actual coercive punishment beyond the public entry of conviction and the sentence with its attendant risks. Courts repeatedly assert that the sentence of suspended imprisonment is the penultimate penalty known to the law and this statement is given credence by the terms and structure of the statute. However, in practice, it is not always viewed that way by the public, by victims of criminal wrong-doing or even by offenders themselves. This disparity of attitudes illustrates the tension that exists between the component parts of this sentencing option: the decision to imprison and the decision to suspend.

[81] A number of attempts have been made to resolve this tension and to provide guidance concerning the circumstances in which a sentence of imprisonment should be suspended. There is a line of authority in Australian courts that suggests that the primary consideration will be the effect such an order will have on rehabilitation of the offender which will achieve the protection of the community which the sentence of imprisonment itself is designed to attain. But most such statements are qualified by judicial recognition that other factors may be taken into account. The point is therefore largely one of emphasis.

Once the sentencing range for some offences was established as jail — even though it might sometimes be suspended — it became very difficult to suggest that it now ought not be jail. It seems to me this is the problem that comes about because of the current government’s desire to label only actual jail as jail. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, and seems to be a lot more logical and intellectually honest about what’s happening in the sentencing process. But it suggests that the effect of the change either wasn’t fully appreciated when the changes were made, or the government didn’t mind that it might mean more people go to jail. IMHO, that’s not a good thing. Jail really should be an option of last resort, rather than a default because there’s no other option permitted to the courts because of the way the legislation is structured. (No matter what your philosophical approach might be to jail, if the purpose of it is to stop people reoffending — whether because they are deterred, or rehabilitated — then it seems it’s not so effective. Combine that with the bad side effects of jail, and it’s worth asking if there should be an alternative in appropriate cases.)

I think the government did mean for CCOs to occupy some of the ground previously occupied by ICOs and suspended sentences, but because the legislation doesn’t say that in those precise terms, it’s open to argument.

Presumably, this would mean that a Court would have to consider the maximum sentence available for a CCO — say, 5 years for recklessly causing injury — and conclude that would still be inadequate before it could then go up the sentencing hierarchy to consider a jail sentence. But again, that’s open to argument as well.

It seems that some courts have accepted this might be the case. The Age reported last year that one offender received a 10-year CCO. But that case, and two others, are before the Court of Appeal after the DPP asked for the first ever guideline judgment in Victoria on the scope and limits of CCOs. I understand those cases were argued on 31 Jul and 1 Aug, and the Court has reserved its decision on whether it will give a guideline judgment, and if it does, what that judgment will be.

Hopefully the Court will provide a guideline judgment, because it seems this is an area ripe for such direction. And hopefully it will agree with the view of the Sentencing Advisory Council. With the abolition of suspended sentences, there is a real need for an intermediate sentencing option that allows for serious punishment without all the brutalising effects of jail. There are some offenders who really are terrified just at the thought of being before a Court, and who truly do suffer significant punishment and experience deterrence without being locked up. On the other hand, there are some offenders who do need to be locked up. Ideally, our justice system should allow out courts to adequately deal with both.

Monday, 5 May 2014

The new edition of Fox & Freiberg on Sentencing

The tools of trade for any advocate are their wits, their tongue, and their knowledge of the law. And none of us can know all the law, and so we often refer to primary and secondary sources.

Richard Fox and Arie Freiberg’s Sentencing: State and Federal Law in Victoria is one of those few secondary sources that is certainly recognised as an authority in its own right, and though not a primary source of law, is one that criminal advocates probably can’t do without. I managed to get one of the few copies remaining when Oxford University Press was running out the last of the second edition, published in 1999. It was still a good source for sentencing principles and policies, but changes to sentencing law had reduced its utility.

As an aside, I discovered a little while ago in a speech from Lord Neuberger that it turns out the “better read when dead” convention — which prohibited conferring the status of the status of authority on a published work until its authors were dead — is not correct, if it ever were. No doubt Arie Freiberg will be pleased to hear this.

So I was very pleased when last Thursday my ProView library updated to download the eBook version of the third edition of this tome, and my hardcopy arrived Friday.

The book or eBook on their own are $260; the two combined are $338. (Link here.) The work is current to October 2013 — I’ve already found legislative references that have been amended since then! — and significantly reworked to discuss the raft of ancillary orders that are made either at the sentencing stage or follow as a consequence of sentencing.

The eBook is excellent — you can see my review of ProView here — and set to display the same as the hardcopy, so there won’t be any confusion when referring to page numbers. However, the table of contents doesn’t have a great deal of depth. So for example, in Chapter 5 ‘General sentencing principles: nature of the offender’, the only contents entry is for the first paragraph, headed Nature of the offender.

The chapter runs for nearly 40 pages, and has about 15 sub-headings, yet none of those show in the table of contents. Tough luck if you want to jump to the last sub-heading emotional stress on page 373! I guess an electronic document like this can be updated, so hopefully we might see a fix to this.

My only other criticism so far is the index is fairly basic, and from what I’ve looked at so far, seems to only have one entry for any given item. A good index with lots of cross-referencing or multiple entries for the same material is an absolute boon. (It’s also a lot of hard work, and adds to the size and cost of a publication, so it always involves a balancing act.)

The other great benefit of the eBook version — something common to most ProView titles — is the ability to export parts of the work to PDF. I can export selected text — the most I can select is a single page; it doesn’t seem possible to select say two-and-a-half pages — or the current view, or a current table-of-contents section. (Which in chapter 5, going on my whinge above, would presently be the whole chapter.) It’s a great feature though, and I can see it being really handy when I want to include the relevant portion of Fox and Freiberg in any material I want to provide to the Bench.

Despite the couple of minor gripes I have, this is a significant update and a great addition to the library of any criminal advocate. It’s not exactly cheap, but well worth it for its authoritative discussion on sentencing law in Victoria, not to mention that it can save literally hours of research for the busy advocate. I reckon it’s a must-have for any criminal practitioner.

Richard Fox and Arie Freiberg’s Sentencing: State and Federal Law in Victoria is one of those few secondary sources that is certainly recognised as an authority in its own right, and though not a primary source of law, is one that criminal advocates probably can’t do without. I managed to get one of the few copies remaining when Oxford University Press was running out the last of the second edition, published in 1999. It was still a good source for sentencing principles and policies, but changes to sentencing law had reduced its utility.

As an aside, I discovered a little while ago in a speech from Lord Neuberger that it turns out the “better read when dead” convention — which prohibited conferring the status of the status of authority on a published work until its authors were dead — is not correct, if it ever were. No doubt Arie Freiberg will be pleased to hear this.

So I was very pleased when last Thursday my ProView library updated to download the eBook version of the third edition of this tome, and my hardcopy arrived Friday.

The book or eBook on their own are $260; the two combined are $338. (Link here.) The work is current to October 2013 — I’ve already found legislative references that have been amended since then! — and significantly reworked to discuss the raft of ancillary orders that are made either at the sentencing stage or follow as a consequence of sentencing.

The eBook is excellent — you can see my review of ProView here — and set to display the same as the hardcopy, so there won’t be any confusion when referring to page numbers. However, the table of contents doesn’t have a great deal of depth. So for example, in Chapter 5 ‘General sentencing principles: nature of the offender’, the only contents entry is for the first paragraph, headed Nature of the offender.

The chapter runs for nearly 40 pages, and has about 15 sub-headings, yet none of those show in the table of contents. Tough luck if you want to jump to the last sub-heading emotional stress on page 373! I guess an electronic document like this can be updated, so hopefully we might see a fix to this.

My only other criticism so far is the index is fairly basic, and from what I’ve looked at so far, seems to only have one entry for any given item. A good index with lots of cross-referencing or multiple entries for the same material is an absolute boon. (It’s also a lot of hard work, and adds to the size and cost of a publication, so it always involves a balancing act.)

The other great benefit of the eBook version — something common to most ProView titles — is the ability to export parts of the work to PDF. I can export selected text — the most I can select is a single page; it doesn’t seem possible to select say two-and-a-half pages — or the current view, or a current table-of-contents section. (Which in chapter 5, going on my whinge above, would presently be the whole chapter.) It’s a great feature though, and I can see it being really handy when I want to include the relevant portion of Fox and Freiberg in any material I want to provide to the Bench.

Despite the couple of minor gripes I have, this is a significant update and a great addition to the library of any criminal advocate. It’s not exactly cheap, but well worth it for its authoritative discussion on sentencing law in Victoria, not to mention that it can save literally hours of research for the busy advocate. I reckon it’s a must-have for any criminal practitioner.

Thursday, 13 February 2014

Barbaro v The Queen; Zirilli v The Queen [2014] HCA 2: High Court modifies prosecutors duties at sentencing

|

| “No” to prosecution submissions on sentencing range. |

In 2008, the Victorian Court of Appeal decided in R v MacNeil-Brown (2008) 20 VR 677 (discussed here) that when asked, prosecutors were required to submit what the prosecution considered was an available range of sentences to impose on an offender, or if the prosecution thought the court would otherwise fall into error.

Even then, it was a 3-2 decision, and that divergence of views is reflected in daily practice in Victorian courts.

But the High Court put a stop to all that yesterday when it delivered its judgment in Barbaro v The Queen; Zirilli v The Queen [2014] HCA 2.

The majority said quite simply:

[23] To the extent to which MacNeil-Brown stands as authority supporting the practice of counsel for the prosecution providing a submission about the bounds of the available range of sentences, the decision should be overruled. The practice to which MacNeil-Brown has given rise should cease. The practice is wrong in principle.

Pasquale Barbaro and Saverio Zirilli pleaded guilty to various offences related to large-scale ecstasy importation and trafficking, after negotiations with the prosecution. Apparently, the prosecution considered that the sentencing range for Barbaro was 32 to 37 years (with a non-parole period of 24 to 28 years), and for Zirilli, 21 to 25 years (with a non-parole period of 16 to 19 years).

But that all came to nought at their sentencing hearing when the sentencing judge said she didn’t want to hear from the prosecution about a sentencing range.

Barbaro received a life sentence (non-parole period of 30 years) and Zirilli received 26 years (with a non-parole period of 18 years).

Both men asked to appeal to the High Court. They had two arguments.

First, plea agreements were made and the cases settled or resolved to pleas, because they expected the prosecution would advise the Court what it thought was the appropriate sentencing range.

Second, they were disadvantaged by not being able to rely on those submissions.

The majority dealt with that pretty swiftly:

[6] The applicants’ arguments depend on two flawed premises. The first is that the prosecution is permitted (or required) to submit to a sentencing judge its view of what are the bounds of the range of sentences which may be imposed on an offender. That premise, in turn, depends on the premise that such a submission is a submission of law. For the reasons which follow, each premise is wrong.They then went on to elaborate on that (see in particular [42] – [43]), and to lay down the law about who does what at the sentencing stage of proceedings.

[47] To describe the discussions between the prosecution and lawyers for the applicants as leading to plea agreements (or “settlement” of the matters) cannot obscure three fundamental propositions. First, it is for the prosecution, alone, to decide what charges are to be preferred against an accused person. Second, it is for the accused person, alone, to decide whether to plead guilty to the charges preferred. That decision cannot be made with any foreknowledge of what sentence will be imposed. Neither the prosecution nor the offender’s advisers can do anything more than proffer an opinion as to what might reasonably be expected to happen. Third, and of most immediate importance in these applications, it is for the sentencing judge, alone, to decide what sentence will be imposed.

The applicants’ allegations of unfairness depended upon giving the plea agreements and the prosecution’s expression of opinion about sentencing range relevance and importance that is not consistent with these principles. The prosecution decided what charges would be preferred against the applicants. The applicants decided whether to plead guilty to those charges. They did so in light of whatever advice they had from their own advisers and whatever weight they chose to give to the prosecution’s opinions. But they necessarily did so knowing that it was for the judge, alone, to decide what sentence would be passed upon them. (Citations omitted.)One of the arguments against this might be that an offender doesn’t have much idea what sentence they might get if they plea to some or all offences, and they’re subject to the judge’s opinion about the proper sentence.

Once response to that is that that’s what happens: judges have the responsibility for making decisions about sentence. It’s a bit like going on a game show and being unsurprised that the announcer might call you at random to “come on down”, or not.

But the other point is in what the High Court said in the quote above: offenders will get advise from their lawyers about the sentence they might expect, but with the caveat that the judge will decide.

The other point to note is that the High Court was only denying a role for the prosecution to submit its views about the range. But it is still open to the prosecution and defence — and probably required as a matter of practice and good advocacy, if not a matter of law — to refer to comparable cases and relevant sentencing statistics.

[40] The setting of bounds to the available range of sentences in a particular case must, however, be distinguished from the proper and ordinary use of sentencing statistics and other material indicating what sentences have been imposed in other (more or less) comparable cases. Consistency of sentencing is important. But the consistency that is sought is consistency in the application of relevant legal principles, not numerical equivalence.What this means is that the parties will now need to advance only the foundation for the opinion they might have once expressed, rather than the opinion (of the proper sentence length) itself.

One side effect of this might be a much more intense focus on the sentencing facts agreed between the parties, because they will now take on an even greater significance in sentencing proceedings. It could be that some cases run to trial simply because the parties can’t agree on that, or else, there might be an increase in contested sentencing hearings.

Thursday, 5 December 2013

Circle the wagons! They say they’re not guilty!

|

| F-Troop's Sgt O’Rourke and Cpl Agarn under defence! |

I’ve heard from colleagues that in some summary case conferences at court or contest-mentions they’re facing declarations that the courts won't permit defence by ambush, and that their accused client is required to disclose any defence they wish to advance.

I guess this might arise from the provisions dealing with summary-case conferences and contest-mentions, ss 54 and 55 of the Criminal Procedure Act 2009.

Section 54 provides for a conference between the prosecution and accused to manage the “progression of the case”, including identifying issues in dispute, and for any purpose provided by the Rules of the Court. And the Magistrates’ Court Criminal Procedure Rules 2009 r 21 indeed provide:

21 Summary case conference

The parties to a summary case conference shall engage in meaningful discussion relating to pre-trial disclosure, issues in dispute and the prospects for resolution of charges.

Section 55 requires the parties to provide estimates of time and witness numbers, notice of facilities that might be required, and relevantly to indicate the evidence that party proposes to adduce and to identify the issues in dispute, and anything else for the case management of the proceeding.

Similar provisions apply also to trials in the County and Supreme Courts. Section 179 provides for directions hearings (and applies only for trials, though I see the Magistrates’ Court has recently purported to rely on this provision to conduct yet more special mentions of matters heading to hearing), and s 183 provides for defence responses to the prosecution openings. (At least that provision expressly states the accused is not required to divulge the identity of any witnesses, or if they will testify themself.)

But none of these provisions expressly state that an accused person must divulge their defence prior to a hearing.

And it seems a little, well, odd to suggest that the prosecution — which brings the charge before the court — might somehow be surprised or ambushed by the accused pleading not guilty and then actually being able to point to a flaw in the prosecution case. After all, that’s the whole point of pleading not guilty.

The common law position

An accused is legitimately entitled to put the prosecution to its proofs, and to rely upon any deficiency, without notice to the prosecution.

A criminal trial is the prime example of an adversarial proceeding. Its adversarial character is substantially unrelieved by pre-trial procedures designed to limit the issues of fact in genuine dispute between the Crown and an accused. The issues for trial are ascertained by reference to the indictment and the plea and, subject to statute, the Crown has no right to notice of the issues which an accused proposes actively to contest. The Crown bears the onus of proving the guilt of an accused on every issue apart from insanity and statutory exceptions. The Crown must present the whole of its case foreseeing, so far as it reasonably can, any “defence” which an accused might raise, for the Crown will not be permitted, generally speaking, to adduce further evidence in rebuttal on any issue on which it bears the onus of proof. The Crown obtains no assistance in discharging that onus by pointing to some omission on the part of an accused to facilitate the presentation of the Crown's case or to some difficulty encountered by the Crown in adducing rebuttal evidence which an accused could have alleviated by earlier notice. Even where an accused proposes to raise an alibi, there is no common law duty to give the Crown notice of the alibi. It was necessary to legislate to require notice of an alibi to be given to the Crown before trial, although a failure to give notice of an alibi might result in the Crown being permitted to call evidence in rebuttal if the alibi is first set up during the defence case. In a criminal trial, an accused is entitled to put the Crown to proof of any issue the onus of which rests on the Crown without giving prior notice of the ground on which he intends to contest the issue. If the ground be some matter of fact, an accused is entitled to abstain from giving notice of the ground until a witness is called during the trial to whom the matter of fact can and should be put: Petty v The Queen; Maiden v The Queen (1991) 173 CLR 95 at 108 per Brennan J.

This is a manifestation of the right to silence, closely related to the principle that the prosecution must prove guilt beyond reasonable doubt.

Nevertheless, the right of an accused to refrain from disclosing his defence until an appropriate stage of the trial, the scope of the right of silence and an accused's freedom to abstain, without prejudice to the conduct of his defence, from cross-examining a witness on committal proceedings are questions of such importance to criminal practice and procedure that special leave must be granted…: Petty v The Queen; Maiden v The Queen (1991) 173 CLR 95 at 111 per Brennan J.

It’s also legitimate for the accused to put the prosecution to its proofs, and to see if it metaphorically trips over its own feet. In HML v The Queen (2008) 235 CLR 334 at 353, [9], Gleeson CJ noted, “It is important not to overlook the legitimate opportunism that may be involved in the conduct of a defence under the accusatorial system of trial.”

Do case-management rules alter anything?

Those passages from Petty were applied in R v Ling (1996) 90 A Crim R 376, a decision from the SA Court of Appeal. In that case, the accused was charged with offences and acquitted by the Magistrates’ Court after calling two witnesses not previously known by or disclosed to the prosecution.

The Magistrate held the accused had breached the relevant case management rules, and so was not entitled to his full costs. The accused appealed that decision.

The relevant rule was Rule 26 of the Magistrates’ Court Rules 1992 (SA), which provided:

26.01 Prior to any matter being listed for summary trial the parties must have ascertained the precise matters in issue both as to fact (in detail) and law as to:

(a) fully explore the possibility of disposing of the charge other than by way of trial;

(b) enable the duration of the hearing to be estimated as accurately as possible;

(c) determine what evidence if any may be proved by affidavit;

(d) facilitate the course of the trial,

and shall inform the court as to each of the above.

26.02 To the extent necessary to comply with this rule the parties must confer fully and frankly.

26.03 Prior to a matter being set down for hearing the defence must give notice to the prosecution if evidence of alibi may be called. The notice must give details of the proposed evidence including the name and address of the witnesses.

26.04 Insufficient compliance with this rule must be taken into account on the question of costs.

26.05 To ensure compliance with r 8 and this rule the court may on notice to the parties require that they attend a pretrial conference.

On the appeal, he Full Court of the Supreme Court of South Australia held that case management procedures which on their face required an accused person to disclose their defence could not abrogate such a basic and fundamental principle as the right to silence.

That being so, it is my opinion that r 26 is not to be interpreted as requiring that before a matter is listed for trial, or indeed at any time, the defence disclose its case, nor as requiring that the defence disclose whether evidence will be called and if so from whom and what that evidence is.

I reach that conclusion despite the imperative language used in r 26 and despite the reference in r 26.05 to r 8 which deals with case flow management…

At a first glance r 26 is so expressed as to suggest that it does require such disclosure, but in my opinion it is clear upon reflection that r 26 must be interpreted as operating in the context of the right of silence, and not as displacing it. It certainly does not displace the right of silence in express terms, and in my opinion there is no necessary implication from its nature and terms that it does so.

…

The rules of all three courts [Magistrates’, District and Supreme] reflect a new emphasis, found also in the rules of many other courts, upon case flow management and upon the obligation of parties to assist the court in the just and efficient determination of the business before it. Courts today accept a responsibility not simply for the just determination of a criminal trial in accordance with traditional criminal procedure, but also for the prompt and efficient disposition of the business of the criminal courts. But while the rules of the courts of this State require the cooperation of the parties to that end, they do not, as I understand them, infringe upon the fundamental right of silence: R v Ling (1996) 90 A Crim R 376 at 380 per Doyle CJ.

Doyle CJ held that to the extent that case management rules purport to abrogate the right to silence, they are invalid in the absence of clear express contrary legislative intention.