Thirty years ago, on September 13, 1990, during an open-air concert at Wingate Field in Brooklyn, Curtis Mayfield suffered the accident that left him paralysed from the neck down. Just over three years later I went to his home in Atlanta, Georgia to conduct an interview that I’ll never forget. Here it is.

“There’s not really much to talk about,” Curtis Mayfield said. “It happened, and it happened fast. I never even saw it coming.” And then, gathering momentum, he started to describe the events of a late-summer day in 1990.

“It was the 13th of September,” he began. “I think it was a Monday. I flew into New York from Long Beach, California. I had my driver come and meet us at La Guardia. Everybody was in good shape. We went over to New Jersey. I had decided to stay in a hotel over there — it was a little cheaper. I got on the phone, called my promoter at about eleven o’clock to tell him we were here. He told me he’d call me back, which he did a little later, and he gave me directions to come out to Queens.

“We arrived there at about eight-thirty or nine. It was bigger than I thought — about 10,000 people right out in the park. We pulled up behind the stage. I met a few people, shook a few hands, got my money — my balance in advance. All the normal things. I’m in the safest place in my life, doing my work.

“I was to close the show, but it was running a little late, and I was asked to go on stage a little early so people who were there to see me wouldn’t be disappointed. No problem. I was happy to do that. I tuned my guitar and jumped into my stage clothes. The promoter’s son came out and said, ‘We’re ready for you.’ I sent my band out and they hit the opening number. It was ‘Superfly’.

“I had my guitar on and I’m walking up these sort of ladder steps, a little bit steep but not so steep you couldn’t walk up them. I get to the top of the back of the stage, I take two or three steps, and… I don’t remember anything. I don’t even remember falling.

“The next thing I know, I was lying on my back. So I must have went out for a moment. And then I discovered that neither my hands nor my arms were where I thought they were, and I couldn’t move. I looked about me lying there. I saw myself totally splattered all over the stage.

“Then it began to rain. Big drops. I could hear people screaming and hollering. From what I could observe, all of everything above us had come out of the sky. I chose not to shut my eyes, for fear of dying. The rain was falling. Some of the fellows found me and saw that I was paralysed, so they went and found a big piece of plastic sheeting to protect me in the rain until the paramedics arrived. Luckily, the hospital was right around the corner. Everything else is history.”

And then, lying in the large bed in the front room of his house, Curtis Mayfield fell silent. His brown eyes peered over the top of the white sheet. The tape recorder, propped on the pillow case close to his mouth, turned noiselessly. Nothing else moved. For Mayfield, nothing had moved since that humid night three and a half years earlier when he took the stage, just as he had done countless times throughout a thirty-year performing career, and a lighting rig toppled, paralysing him from the neck down and silencing one of the great poetic voices of post-war America.

####################

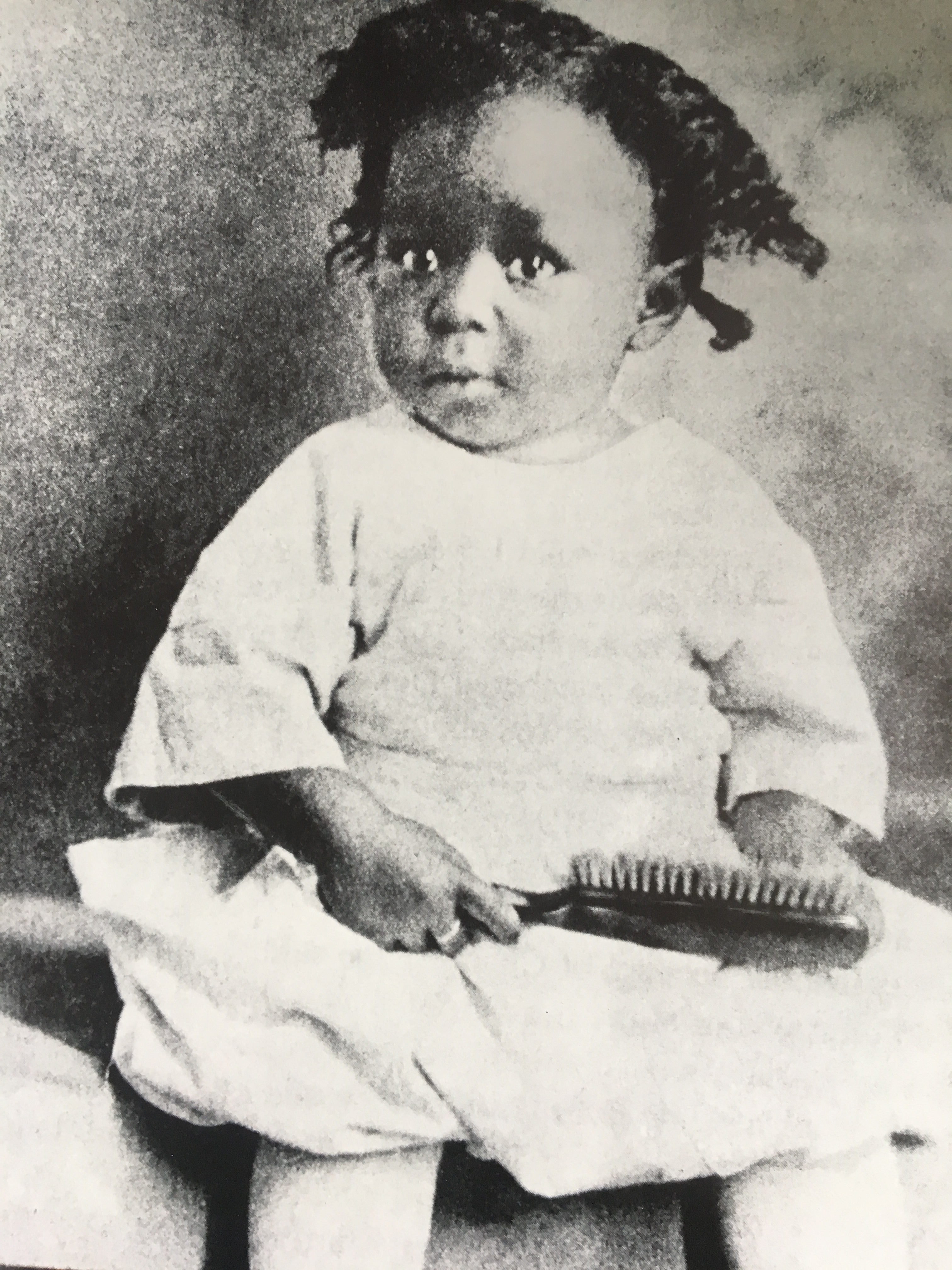

He was born in 1942 and grew up in the Cabrini-Green housing projects on Chicago’s Near North Side. His father left home when he was four years old and he was raised by his mother. But when he talked about where he had acquired his view of the world, and his means of expressing that view, he kept returning to memories of his grandmother.

“I used to be back and forth between my mother and my grandmother,” he said. “She was the Reverend Annie Bell Mayfield, and she had a little storefront church — the Traveling Soul Spiritualist Church. We’d have Bible classes there early on Sunday mornings before my grandmother’s sermons, which would go on from nine o’clock in the morning until noon.” Annie Bell Mayfield died some years ago, leaving no evidence of her prowess as a preacher, but it’s easy to believe that, if we were somehow able to retrieve an replay her Sunday morning marathons, we would hear the distinctive patterns that distinguish not only her grandson’s lyrics but also, from time to time, his conversation, in which ghetto vernacular is articulated with a graceful formality that can only have come from early and prolonged exposure to the King James Bible.

He began to sing, too, in her church, where he also heard many styles of gospel music performed by visiting choirs, an experience that augmented a fondness for the recordings of the Sensational Nightingales and the Original Five Blind Boys of Alabama — “on that black and white Specialty label, in the days when I had to stand on tiptoe to reach the Victrola.” At home, where his mother kept the family together through welfare payments, there was always a record on the Victrola or something playing on the radio, and he quickly learned to love the grown-up popular music of Billie Holiday as well as the teenage doo-wop of the Spaniels, the Cadillacs and Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers.

At eight or nine he was singing alongside a young friend, Jerry Butler, in a gospel group called the Northern Jubilees. In his early teens, having picked up a rudimentary knowledge of the piano, he started fooling around a guitar that a friend had left at his grandmother’s house. Knowing nothing, he tuned it to the black keys of the piano. The result was an F-sharp open tuning which he discovered was incorrect, or at least unorthodox, when he and the Impressions made their first visit to the Apollo in Harlem and he tried playing along with the house orchestra. “No one else tunes that way,” he said with sadness, the arms that had cradled that guitar lying immobile under the bedsheet. “So it’s a lost art now, a lost tuning.” At eleven or twelve he was singing with schoolboy doo-wop quartets, using housing-project stairwells as echo chambers, and before long he was writing songs for them to sing. His guitar was the vehicle, and his imagination provided the material.

“Everything was a song,” he said. “Every conversation, every personal hurt, every observance of people in stress, happiness and love. If you could feel it, I could feel it. And if I could feel it, I could write a song about it. If you have a good imagination, you can go quite far.”

His mother encouraged him to read widely, and introduced him to the work of the black poet Paul Laurence Dunbar. “My teacher told me I’d never amount to anything,” he said. “I left high school at fifteen, after just one year. But my real teachers were the people around me. And I was a good listener. I used to love to sit and listen to the old people talk about yesterday. There’s a lot of good information there.”

The sharp awareness of social problems came, he said, simply from looking at the world around him. “I was a young black kid. One of the first things I remember, in the early ’50s, was the boy from the north who went to Mississippi to visit and happened to say something or whistle to a white woman. They came and got him out of the night and destroyed him.” He was referring to fourteen-year-old Emmett Till, murdered in 1955 by white racists for his alleged effrontery. “All of these things come into your head. And of course the popularity of the Reverend Martin Luther King instilled in me the need to join in, to speak in terms of we as a minority finding ways to be a bit more equal in this country.”

The record industry wasn’t exactly thrilled by the notion of a black entertainer trying to say something serious in songs with the Impressions like “We’re a Winner”, “Choice of Colours” and “Mighty Mighty (Spade and Whitey)”. “No, no. But I didn’t care. I couldn’t help myself for it. And it was also my own teachings, me talking to myself about my own moral standards. As a kid, sometimes you have nobody to turn to. I could always go back to some of the sermons and talk to myself in a righteous manner and put that in a song.”

I asked him where “People Get Ready” had come from, because it seemed to be one of those songs that had sprung not from a writer’s pen but from the collective unconsciousness. “I don’t know. I just wrote it. Lyrically you could tell it’s from parts of the Bible. ‘There’s no room for the hopeless sinner who would hurt all mankind just to save his own / Have pity on those whose chances grow thinner, for there’s no hiding place against the Kingdom’s throne.’ It’s an ideal. There’s a message there.”

Mayfield had hardly begun writing songs before he realised the value of owning the title to his own work. “My family had been quite poor. We had nothing, really, although I didn’t realise it when I was small. But once I came of an age to understand how little we had, it made me want to own as much of myself as possible.” And at the age of seventeen this Chicago ghetto child wrote off to the Library of Congress in Washington DC, asking how he could protect the rights to his own songs. Form a publishing company, they told him, and this is how you do it. So he did.

“During that time,” he said, “record companies were used to taking people off the street and giving them twenty five bucks for a song. Many a hit came off the street like that. But I was too stubborn, too strong-willed, which they didn’t care for. However, I also understood early on that it’s better to have fifty per cent of something than a hundred per cent of nothing. And at least I had it to bargain with.”

The business side didn’t come naturally to him. “I’m a creative person. And I was just too young. I didn’t have the knowledge. I’m sure that for every dollar I’ve earned, I’ve probably earned someone else ten or twenty dollars.”

The Impressions recorded first for the local Vee Jay label and then for the giant ABC corporation, where their hits ran from “Gypsy Woman” and “It’s All Right” through “I’m So Proud”, “Amen, “Keep on Pushing”, “Meeting over Yonder”, “You’ve Been Cheating” and “I Need You”. But in the late ’60s, inspired by Berry Gordy’s Motown enterprise, he and a partner, Eddie Thomas, who had been Jerry Butler’s chauffeur, formed their own label. Like the Isley Brothers’ T-Neck or James Brown’s People label, Mayfield’s Curtom Records never quite managed to outgrow its primary function as a vehicle for the founder’s musical output.

“We were all trying to survive in a big world of business and loopholes and record companies that weren’t giving you all you felt you’d earned,” he said. “I just admired what Berry was doing at Motown. I always had that dream. But it just never happened for me in that manner.” Why not? “I wore too many hats, for one thing. And my face during those days would not allow doors to open for me. As a black man, you don’t get an invitation.”

####################

Mayfield was in his prime in 1972, aged thirty, when he used the soundtrack to Superfly — one of a series of “blaxpolitation” movies — to deliver a warning against the increasingly violent drug culture of the projects in which he had grown up. I wondered whether it saddened him that although the songs were big hits, the warnings of “Freddie’s Dead” and “Pusherman” — like those contained in James Brown’s “King Heroin” or Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On — had been so totally ignored by the people at whom they were aimed, even though they were also often the people who bought and danced to them.

“In some ways. Not really, because although sometimes all the bad things seem to be in a majority, it’s still really a small minority. The majority still has high hopes and reasons, and wants to do the right things and be about success stories. The poverty may hold them back, but the dreams are still there. People have reasons to be pessimistic, but this world is still of value.”

But wasn’t he nevertheless glad that he had grown up in the Chicago of the ’40s and ’50s, where black people were still streaming in from the South, fleeing the plantations in the hope of a better life, rather than the crack-culture Chicago of the ’90s, where the only solution to the hopelessness of the Cabrini-Green projects was to raze them to the ground? Weren’t things just getting worse?

“It’s hard to say who lived the better life. However, those who live today would probably prefer today’s life, and tomorrow’s beginning. We laid the ground, our sacrifices were big. But prior to that it was even worse. And look at the people who laid a platform for us. I understand what you’re saying. It seems that it’s not respected or appreciated by many of the young. But I still say it’s a minority of a minority. It’s not the majority.”

Mayfield has eleven children. Six of them were living with him and his wife, Altheida, in the big house in the Atlanta suburbs that he bought in 1980. What did he think of the music that had soundtracked the growing years of his own kids — the brutal frankness of hip-hop and gangsta rap?

“I listen to it, and it hurts me. A lot of the stuff, as a grown adult and a father… well, you do have to lay down your own laws and not allow too much of it to infiltrate the home and family.” Is it really corrupting? “Oh yeah. Children are very impressionable. You do have to set standards and lay a foundation of rights and wrongs, and then live a certain way so that they can see that what you say is also what you do. And if your children have any strength and an admiration for their parents, and if you teach them to be strong-willed, then maybe — just maybe — you have a chance. That is still not to say that as they leave this home and go out into the world they may not be smothered with all the negatives — knowing that black boys especially have less than a fighting chance to learn the things they need to make a livelihood. All that’s out there for them is jail.”

Lying there in his enforced silence, would he like to be writing about those matters today?

“No. It’s all been said. And I don’t like to repeat myself.”

####################

He had surgery straight after the accident, and again once he was back home in Atlanta. But nothing had improved his condition, which appeared like to be unchanged for the rest of his life. He relied on his wife and children to feed him, to fetch for him, and for every movement of his limbs. All he had left were his eyes, his speech, his brain, and his enormous spiritual and philosophical resources.

“We’re taught to keep high hopes,” he said when I asked him about a prognosis. “Which I have. But I must deal with the realities of today, and let tomorrow take care of itself. I’m lucky to still have my mind. Many things are possible. But if I have a thought, I can’t write it down. I even have a computer over there. But I can’t get up to use it. So there are those frustrations.”

Could he still sing? “Not in the manner as you once knew me. I’m strongest lying down like this. I don’t have a diaphragm any more. So when I sit up, I lose my voice. I have no strength, no volume, no falsetto voice, and I tire very fast.”

But did he still sing inside his own head? “Yes, I do. I still come up with ideas and melodies. But they’re like dreams. If you can’t jot them down immediately, they vanish.”

His medical bills had been horrendous. To help defray them, a tribute album featured performances of his songs by singers from Aretha Franklin, Whitney Houston, Bruce Springsteen and Gladys Knight to Elton John, Rod Stewart, B. B. King and the Isley Brothers. He expressed gratitude to BMI, one of the two big US royalty-collection agencies, which helped out by paying him an advance against each year’s earnings. Surely, I suggested, they must have done pretty well out of him over the years? “I hope so. But, you know, people don’t have to. In my case lots of people have in their own ways been ready to come to my aid. I try not to ask. I don’t wish for charity. But I must still realise that I’m in need of everybody.”

A young man came into the room: Todd Mayfield, aged twenty seven, his second son, wanting to see if his father needed anything.

“My family has been fantastic,” said the quiet voice from the bed. “My son here is my legs and my arms and part of my mind as well.” A pause. “So… so far, so good.”

* Curtis Mayfield died on December 29, 1999, aged fifty seven. Three years earlier, helped by various musicians and producers, he had made one last album, the superb New World Order, released by Warner Brothers, from which the portrait photograph by Dana Lixenburg is borrowed. Traveling Soul, Todd Mayfield’s excellent biography of his father, was published in 2017 by the Chicago Review Press. My piece originally appeared in the Independent on Sunday and is slightly abridged from the version included in Long Distance Call, a collection of my music pieces, published in 2000 by Aurum Press.