When capitalism hits one of its inevitable troughs someone has to take the blame for our subsequent problems. All too often minority groups consisting of the 'other' become the fall guy and they become the focus of attention, as if removing them from the equation will cure our ills and put us all back to work. Socialists argue that the focus should remain firmly on the goal of removing the root cause of the problem, ie the capitalist system. Economic migrants, asylum seekers, Palestinians, Greeks, Roma - they are all people; seeking a better life, or simply a life - a way of providing for themselves and their families. What are we if we cannot see that any one of us could so easily become the 'other' in slightly different circumstances? The global majority has a common enemy, one we must be united against - capitalism.

JS

By Sofiane

Ait Chalalet and Chris Jones

Wasim is a refugee from Syria. In

late July he was dropped by boat on a remote, densely wooded and rocky

shore of Samos island, with his wife, young son and baby daughter.

Without enough water or food, he swam to find help. Ignored by passing

boats, he eventually found help, and from there went to the police. He

was immediately arrested and held for a subsequent six weeks. Throughout

this time and despite, from the beginning, pleas that someone look for

his wife and children, he heard nothing from or about them. Six weeks

later he would find them dead.

We

first met Wasim Abo Nahi at the beginning of September. He had just

returned to Samos island in the eastern Aegean from Athens, where he had

been held for processing as an undocumented refugee. He was accompanied

by his nephew, Abdalah and Mohammed, a friend from Athens. All of them

are Palestinian refugees.

Wasim had

returned to Samos to search for his wife, Lamees, his 9-month-old

daughter Layan, and 4-year-old son Uday, whom he had left on the island

six weeks earlier when he was detained. He was overwhelmed with anxiety

as none of their families or friends had heard anything from Lamees

during those weeks. He feared that they were dead, but as no trace of

them had been found he hoped that they were still alive and being

sheltered somewhere on the island.

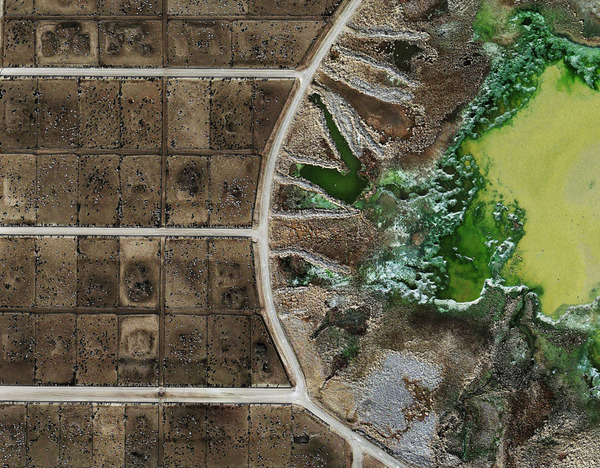

Wasim’s

deepest fear was that his family had perished in the forest fire which

had engulfed the remote mountain side soon after he had left them in his

desperate search for help after they had landed from Turkey. It was to

this area desolated by the fire that we returned on Sunday September 11.

Even scorched and burnt it was a difficult terrain with no paths or

roads where we had to break through charred shrubs to make any progress.

With Wasim leading the way we eventually found the place where they had

first landed. There were some baby clothes and pampers. Importantly,

they were just outside the area of the fire so there was still hope,

although the fact that there had been no sighting of the family or

contact with her cast a despairing shadow.

Wasim

was desperate to find them. Every day he and his friends scoured the

mountain side, sometimes accompanied by a few police officers and a

couple of volunteers from an Athens-based human rights group. On Friday

afternoon, Mohammed, Abdalah and Sofiane found some heavily charred

remains and gold bracelets worn by his children and wife. Although we

now await the results of the DNA tests on what little remains, we have

little doubt that these are the remains of Wasim’s family.

Sadly,

Wasim’s tragedy is all too common. There is abundant evidence that many

men, women and children continue to die at the borders of Europe as

they flee their homeland as refugees. And if they survive and breach the

frontier and arrive, as they do every week, on islands close to Turkey

–such as Samos — they are then treated as criminals and subject to all

kinds of de-humanising treatment. In this sense, the direct cause of the

death of Wasim’s family may have been the fire, but in truth it was a

much bigger set of policies and politics which killed his family. If

these tragedies are to be avoided — as they can and should be — it is

these wider systems and processes that need to be changed.

Fleeing

the conflict engulfing Syria and the Palestinian refugee camp in

Latakia where they had lived, their options were severely limited.

Wasim’s passport, which identifies him as a Palestinian refugee living

in Syria, is worthless as a travel document. None of the neighbouring

Arab states recognise this passport and would refuse him entry. The same

applies to much of the rest of the world, which ruled out travelling to

Damascus and leaving by plane which he could have afforded. So he took

the route of thousands of refugees without papers and travelled through

Turkey and paid 7.000 euros to be brought across the narrow stretch of

the Aegean to Samos. The legacy of the Nakba, when so many Palestinians

like Wasim’s grandparents and parents fled cities such as Haifa in 1948,

runs deep and continues to condemn thousands to miserable lives in

refugee camps, where their rights are deeply compromised and limited.

This needs to change.

But whatever

their nationality, what kind of world forces refugees fleeing for their

lives and their sanity to go “underground” in order to find safety? Why

are they exposed to such vulnerabilities and exploitation which leads so

many to dangerous boats and end expensive routes into Europe? In the

case of Wasim, this led to him and his family being dropped on a rugged

and isolated part of Samos which trapped him and his young family. They

couldn’t get out. This needs to change.

Much

of Wasim’s experience in Samos and Athens was framed by the

demonisation of undocumented refugees and migrants both here in Greece

and sadly throughout much of Europe. As soon as Wasim and his family

took the small boat from Turkey to Samos, this context of hostility

kicked in as they evaded the patrols of the border police (Frontex) and

the Greek coastguard. Samos is not just another Greek holiday island. It

is on the very frontier between Europe and Asia. Its waters are not

simply full of bathing tourists but the more sinister para-military

patrol boats that daily motor around its shores. It is as if we were at

war. The refugees need to be repulsed. They are the enemy. These ideas

have to be changed. They are abhorrent.

The

consequences, as Wasim discovered, are deadly. In his case it meant

instant incarceration, handcuffed in a police cell when he eventually

made it out of the forest seeking help for his family. It led to his

pleas being ignored by the authorities for days before a small effort

was launched by the police to find his wife and children. Cruelly, it

led to him being abandoned by the emergency services after he had made

contact by his mobile phone when he realised that his family were stuck

and in a desperate situation as their water ran out. During their first

night on the island, a patrol boat had located them on the shore but it

never returned. Had it been a family of young European tourists in such a

position, there can be no doubt that the response would have been

completely different. This should not be tolerated.

The

police and other state agencies have much to answer for, but this is

not enough. From the highest levels, both in Greece and throughout

Europe, a policy and ideology has been created which presents a warped

construction of undocumented refugees as a danger and a threat. There is

no element of humanity. The response of the state is that of arrest,

imprisonment and removal. The facilities provided which are regularly

and routinely condemned by NGOs and intergovernmental refugee agencies

as unfit for human life illustrate this all too well. Even if some of

those working in these facilities are deeply moved by the suffering they

encounter, the system remorselessly grinds on. This needs to change.

What

has caused so many here on Samos to feel shame about what happened to

Wasim and his family is the way in which these ideas and practices have

spread. When Wasim left his trapped family to seek help he went back

into the sea and swam around the coast until he could see a way out to a

small house. Whilst in the sea he shouted for help to the small fishing

boats that passed by. Some responded and came over to him but then

turned away when they saw he was a refugee. As one young friend asked,

“what has happened to us that we could do such a thing?”

The

answer sadly is that the Greek state has made many (but not all) too

afraid to help anyone who is a refugee. It is more than probable that

the fishermen who failed to rescue Wasim were fearful that their boats

would be confiscated if they helped. One of our friends had his car

confiscated and then sold by the state when it was found that he was

carrying undocumented refugees. Another friend, an older woman who runs a

small guest house was terrified when four Iranian refugees turned up

wanting a room to shelter in prior to catching the ferry to Athens. She

feared that she would lose her guest house if the authorities discovered

her helping them, although she did.

Earlier

this summer, two Pakistani refugees — with papers — were prosecuted on

Samos for “illegal hospitality” as they had offered room to two

undocumented refugees. Making people fearful, scaring them into losing

their humanity, is a terrible thing to do to someone. This is happening

here. It cannot and should not be tolerated.

In

the meantime, Wasim is overwhelmed by grief. He only wanted to bring

his family to safety, he says. Instead he brought them to their death.

For his sake, and all those other thousands of refugees, who without

papers are invariably poor, we have to find ways to change these

policies, practices and ideologies which kill and wound and which

distort the humanity of us all.

By:

Sofiane

Ait Chalalet is Algerian and came to Samos 7 years ago as a refugee.

Chris Jones is British and came to live in Samos 6 years ago after 30

years as a social science teacher in English higher education. They now

report here on the impact of the unfolding humanitarian crisis on daily life in Samos and the cruel fate of refugees trapped in Greece.

.jpg)