Dissent Magazine

A Quarterly of Politics and Culture

"A pillar of leftist intellectual provocation" writes the New York Times, "devoted to slaying orthodoxies on the right and on the left." www.dissentmagazine.org

twitter.com/DissentMag

Liked posts

-

View high resolution

View high resolution

How Racism Became Policy in Ferguson

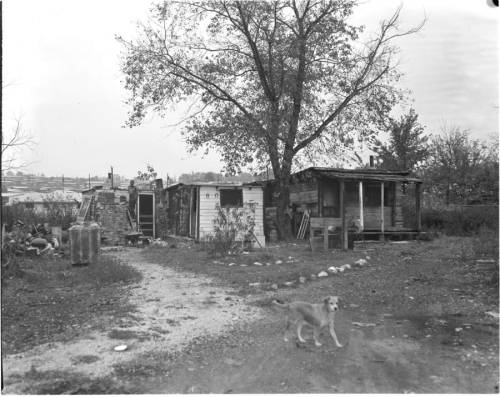

If nothing else, the Justice Department’s Report on the Investigation of the Ferguson Police Department, released last week, gives us a broader context for Michael Brown’s death last August. This is not, we are reminded, simply about the culpability of a rogue or panicked officer. It is about a systematic pattern of oppressive and petty policing, driven in equal parts by local racism and local fiscal incapacity. In the inner suburbs of St. Louis, law enforcement maintains the color line and—in the absence of a stable property tax base—it pays the bills. But this ugly glimpse of the institutional culture of the Ferguson Police Department still only gets us so far. In order to fully understand how and why race became the central premise of policing in the St. Louis suburbs, we need to take another step back and consider the long and troubled history of segregation in St. Louis County.The first part of this history is one of quarantine. Long before it was subdivided into the western suburbs of St. Louis, St. Louis County was home to a few African-American enclaves—including Elmwood Park, Meacham Park, Malcolm Terrace, North Webster Groves, and Kinloch (just to the west of current-day Ferguson). As postwar growth carved the cornfields into cul-de-sacs, suburban development skirted these enclaves, and the infrastructure that came to the new white suburbs—roads, sewers, water—came to a screeching halt at their boundaries.The motives and the consequences were unmistakable. In 1937, the city of Berkeley, Missouri was created, on a peculiar half-donut plot, for the express purpose of cleaving the residents of Kinloch (99.3 percent black) into a separate and segregated school district. In 1960, a polio outbreak in Elmwood Park was traced to the absence of potable water, in a neighborhood surrounded by conventional suburban development in Overland to the north and Olivette to the south. In 1965, five children died in a horrific fire in Meacham Park: the unincorporated neighborhood of 100-odd black families was not part of the local fire district and its rickety community fire truck would not start. In the 1970s, even the United Nations took notice of the fact that Meacham Park, at the heart of suburban central county, lacked basic sanitary sewer service.Read Colin Gordon’s full piece here.

Filed under: racism, urban policy, Ferguson, Justice Department, Ferguson report,.

"Well Liked" by Peter Vidani. For Tumblr.

© 2012–2021 Dissent Magazine