“And now he was playing, alas, the piano,” the first sentence of Robert Walser’s short prose text written in 1925, “making it sound like a deep and intimate promise, which isn’t at all the way to start a novel.” An absence of pianos throughout Daniel Blumberg’s On&On&Onetc, the title of which has the potential to be as long or longer than the famous word invented by James Joyce in Finnegans Wake to sound out the catastrophic fall of a once wallstrait oldparr, makes it easier to enter its world of cords and fibres. Songs, it could be said, were invented to exclude the sound of rooms. They formulate an enclosed world. In the same way that a line of a drawing immediately proposes a hierarchy between mark and ground, the scrape of a string announces itself as the most compelling of airs within a room. At that moment, it hovers between room and song.

I hear a room, its air and the disturbances that ricochet between its surfaces, then I hear a song, as if a ship has slowly emerged out of sea mist, its form coalescing into coherent shape for the sake of memory. Doors open and close. At a given moment of life, songs may come to seem silly, Daniel muses, but then a song comes along, a country song perhaps, to articulate that cluster of emotions indelible within loss, fatigue of the spirit, a faltering of life. The song sounds a deep and intimate promise, to be fulfilled or honoured. If we go back in history, then air, or ayre, or aria, was a term through which a certain kind of musical style or accompanied song was known. To go back to Dowland, for example, or Purcell, and hear the febrile physicality of plucked and bowed strings in close wood-lined rooms. In the absence of pianos, On&On is characterised by a similar stringy physicality, reminiscent of chicken feet, a spider’s web, loosely woven fabric or grasses moving in a breeze, fibrous ligaments, claws and sand, insect stridulation, Violin, cello, bass, guitar. Then there are drums, like rats running over an unbrushed floor, disturbing matchboxes and loose quantities of steel shot in the haste of their purpose to avoid a snare. Behind the snare drum’s head there are strings, steel now, once fibrous.

There are wet cords of voice and dry cords of string; then a harmonica, filleted air bent out of shape by thin brass tongues not unlike the tongues of geese or swans. All of these instruments share an ancestry in their parts. Robert Walser argued that horses are unduly put to work, having no voice with which to express dissent. Similarly, fragments of cat, tree, goat, calf, elephant, bamboo and other entities were once unduly put to work in the service of music, unable, as Walser put it, to negotiate. Some of this unbalanced relationship, its intensity and violence, persists in the music as an echo, a dry echo, a whistle of friction that might be a ghost in the dark. Then there are other strings, collectively played in concert, as if a window has opened and the song also rises on thermals and cloud shapes.

There is no speaking about where a song begins or ends, says Ute Kanngiesser. It’s not important. A song may move around, expand, come apart in its limbs and joints and skin to sink back into the room space, where strings are vibrating, snares rattling. A string is a line drawn taut. Ute speaks about the sessions in Wales during which this record was produced: “A strong memory is of me spending what remained of the night on the porch and watching the lunar eclipse. January 2019. It was the wolf moon and the super moon and the blood moon and it was eclipsing. I watched the moon getting darker, a sepia colour, and the moment it disappeared completely, the owls started a choir from the forest. It was incredible.”

A string is a kind of line, and just as a string may become a song so a line may become a curious figure, displaced head, limbs, face and brightly coloured clothes, all bent, scattered and tumbling in air space. Like the ghost notes of a country shuffle, they fall in and out of worlds. “If I sit at the piano or I’m on the motorbike, I hum songs,” says Daniel. Between improvisation that comes into being in a room and songs that have come into being on a motorbike, there is another music, waiting for its cue in the forest. A song may come and go, on and on and on and on.

Written for the release of Daniel Blumberg’s LP: On & On (released July 31st, 2020)

Surprise is a dubious pleasure, cultivated in the search for musical forms that take the listener into realms of impossible/imaginary. Then suddenly, after decades of searching, the surprises diminish in quantity, often in quality, leaving an unavoidable sense of melancholy, mixed with the treacherous air of nostalgia.

Surprise is a dubious pleasure, cultivated in the search for musical forms that take the listener into realms of impossible/imaginary. Then suddenly, after decades of searching, the surprises diminish in quantity, often in quality, leaving an unavoidable sense of melancholy, mixed with the treacherous air of nostalgia.

Maybe a coincidence but during our Sharpen Your Needles event last night (28.09.17) Evan Parker played “Music for Mbale (Ndokpa)”, from The Photographs of Charles Duvelle: Disques Ocora and Collection Prophet, a sumptuous book and two CDs published by Sublime Frequencies. Recorded by Duvelle in Ngouli, Central African Republic, in 1962, the instrument played by two men for the Mbale village festival was a lingassio, a four key xylophone mounted over a pit.

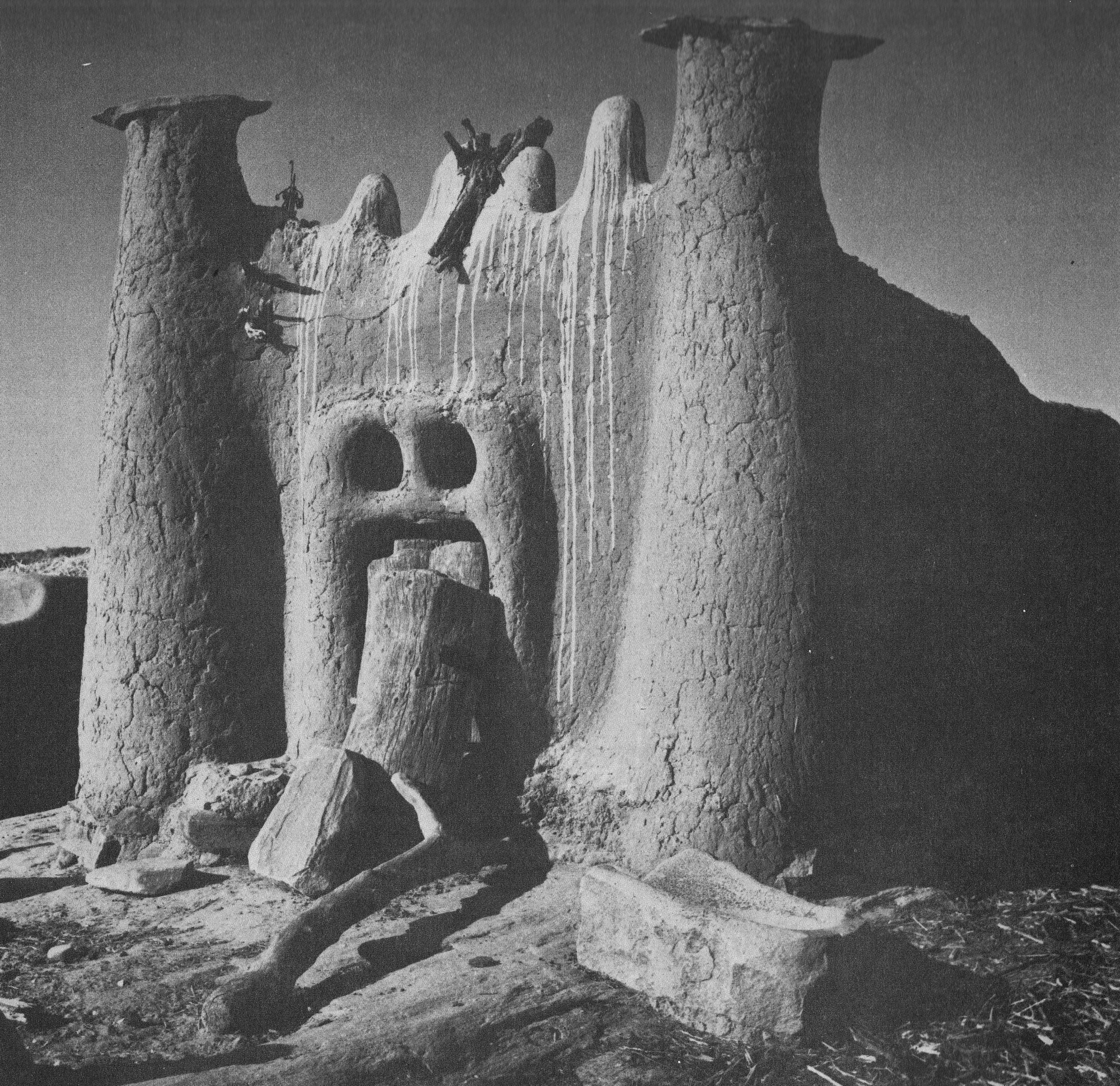

Maybe a coincidence but during our Sharpen Your Needles event last night (28.09.17) Evan Parker played “Music for Mbale (Ndokpa)”, from The Photographs of Charles Duvelle: Disques Ocora and Collection Prophet, a sumptuous book and two CDs published by Sublime Frequencies. Recorded by Duvelle in Ngouli, Central African Republic, in 1962, the instrument played by two men for the Mbale village festival was a lingassio, a four key xylophone mounted over a pit. One lesson to be learned from this is not to jump to easy conclusions about earth instruments and primitivism. The Dan had other ways of amplifying sound, as the above photograph shows, but terra-technology floated somewhere out on the edges of society, either marginal, in the sense of being a diversion for the melancholy and immature, or spectral, as sound masks emitting the voice of a supernatural being. When I was beginning to research non-western music in the early 1970s unilinear cultural evolutionism was still prevalent. To find any subtlety in the literature you had to read ethnomusicologists like Klaus P. Wachsmann (father of improvising violinist Philipp Wachsmann). In my early twenties I was excited to read his chapter – The Primitive Musical Instruments – in Musical Instruments Through the Ages (edited by Anthony Baines, 1961). “While considering them,” he wrote, “it must be borne in mind that the effectiveness of a musical instrument can only be measured by the degree of satisfaction its sound gives to the people who use it.” He devotes a short section to what he called Ground Instruments: ground zithers, percussion beams, stamping pits, ground bows and, most fascinating of all: “In Abyssinia a narrow, tapering hole is made in the ground and howled into; the vernacular name of this instrument means ‘lion’s call’.”

One lesson to be learned from this is not to jump to easy conclusions about earth instruments and primitivism. The Dan had other ways of amplifying sound, as the above photograph shows, but terra-technology floated somewhere out on the edges of society, either marginal, in the sense of being a diversion for the melancholy and immature, or spectral, as sound masks emitting the voice of a supernatural being. When I was beginning to research non-western music in the early 1970s unilinear cultural evolutionism was still prevalent. To find any subtlety in the literature you had to read ethnomusicologists like Klaus P. Wachsmann (father of improvising violinist Philipp Wachsmann). In my early twenties I was excited to read his chapter – The Primitive Musical Instruments – in Musical Instruments Through the Ages (edited by Anthony Baines, 1961). “While considering them,” he wrote, “it must be borne in mind that the effectiveness of a musical instrument can only be measured by the degree of satisfaction its sound gives to the people who use it.” He devotes a short section to what he called Ground Instruments: ground zithers, percussion beams, stamping pits, ground bows and, most fascinating of all: “In Abyssinia a narrow, tapering hole is made in the ground and howled into; the vernacular name of this instrument means ‘lion’s call’.” The allure of such an instrument, hole within a hole, absence within absence, Is out of all proportion to its simplicity. One contribution to the above mentioned social media thread came from Ilan Volkov, who drew my attention to Christian Wolff’s Pit Music (1971), published in Prose Collection. The piece could easily be a description of how to make your own version of the Dan earth bow, though that seems unlikely as both Zemp’s book and Wolff’s composition emerged in the same year. As Ilan pointed out, Wolff never intended his Pit to be actually made. Like a lot of things, post-Fluxus, it was an indication of potential (political as much as anything) rather than an imperative. I wrote similarly provisional pieces a few years later, the Wasp Flute that was never put into practice even though the instrument was built, and hypothetical events in which I performed with seals and fish, all of them suggestions of how life might be lived in a world less traumatised by what Timothy Morton has called The Severing (in his new book, Humankind: Solidarity with Nonhuman People).

The allure of such an instrument, hole within a hole, absence within absence, Is out of all proportion to its simplicity. One contribution to the above mentioned social media thread came from Ilan Volkov, who drew my attention to Christian Wolff’s Pit Music (1971), published in Prose Collection. The piece could easily be a description of how to make your own version of the Dan earth bow, though that seems unlikely as both Zemp’s book and Wolff’s composition emerged in the same year. As Ilan pointed out, Wolff never intended his Pit to be actually made. Like a lot of things, post-Fluxus, it was an indication of potential (political as much as anything) rather than an imperative. I wrote similarly provisional pieces a few years later, the Wasp Flute that was never put into practice even though the instrument was built, and hypothetical events in which I performed with seals and fish, all of them suggestions of how life might be lived in a world less traumatised by what Timothy Morton has called The Severing (in his new book, Humankind: Solidarity with Nonhuman People).

While eating shojin ryori cuisine outdoors at Izusen, Daitokuji temple, Kyoto, in spring sunshine, April past, I reflected on François Jullien’s In Praise of Blandness, the appreciation of blandness or insipidity in ancient Chinese aesthetics and ritual practices. Commenting on a text describing the use of muted music during ritual offerings to the ancestors he says this: “For the most beautiful music – the music that affects us most profoundly – does not . . . consist of the fullest possible exploitation of all the different tones. The most intensive sound is not the most intense: by overwhelming our senses, by manifesting itself exclusively and fully as a sensual phenomenon, sound delivered to its fullest extent leaves us nothing to look forward to. Our very being thus finds itself filled to the brim. In contrast, the least fully rendered sounds are the most promising, in that they have not been fully expressed, externalized, by the instrument in question, whether zither string or voice.

While eating shojin ryori cuisine outdoors at Izusen, Daitokuji temple, Kyoto, in spring sunshine, April past, I reflected on François Jullien’s In Praise of Blandness, the appreciation of blandness or insipidity in ancient Chinese aesthetics and ritual practices. Commenting on a text describing the use of muted music during ritual offerings to the ancestors he says this: “For the most beautiful music – the music that affects us most profoundly – does not . . . consist of the fullest possible exploitation of all the different tones. The most intensive sound is not the most intense: by overwhelming our senses, by manifesting itself exclusively and fully as a sensual phenomenon, sound delivered to its fullest extent leaves us nothing to look forward to. Our very being thus finds itself filled to the brim. In contrast, the least fully rendered sounds are the most promising, in that they have not been fully expressed, externalized, by the instrument in question, whether zither string or voice.