Surprise is a dubious pleasure, cultivated in the search for musical forms that take the listener into realms of impossible/imaginary. Then suddenly, after decades of searching, the surprises diminish in quantity, often in quality, leaving an unavoidable sense of melancholy, mixed with the treacherous air of nostalgia.

Surprise is a dubious pleasure, cultivated in the search for musical forms that take the listener into realms of impossible/imaginary. Then suddenly, after decades of searching, the surprises diminish in quantity, often in quality, leaving an unavoidable sense of melancholy, mixed with the treacherous air of nostalgia.

The antidote is to recognise that ‘new and unfamiliar’ has become stale; the truly new and unfamiliar has opened up regions that feel somehow incomprehensible or distasteful. Aesthetic proclivities become old, just like the bodies that shape them.

I was surprised to be surprised, then, hearing Ami Yamasaki perform with Charlie Collins at Iklectik. Charlie plays a low-lying drum kit and his contributions to this duo were correspondingly low, as in subtle. As interventions they added a halo, a subterranean murmur, a transient glow. At times they gave Ami occasion to smile, in itself an unusual event in improvisation, given the more familiar seriousness of facial expressions.

What was the cause of this experience, through which at times I questioned what I was hearing, or my interpretation of it? Her voice is high and powerful, nothing surprising about that, but its relation to her body is strangely ambiguous. At times, this unearthly voice seems to emanate from somewhere around her body, close to but detached, sometimes corresponding to lip movements and mouth opening but at the end of phrases drifting out of sync. It reminded me of sections in the Béla Tarr/Agnes Hranitzky film, The Man From London, in which dubbing goes adrift in such a way that questions about production difficulties or deliberate dislocation battle each other with a clamour that threatens to overwhelm the course of the film.

She also uses, or seems to use, the ventriloquist technique of projecting her voice, creating the illusion of a voice closer to walls or surrounding air than its original source. All of this is a form of echo-location, commonly used by people who are sight-impaired yet hearing enhanced. Human potential, in other words. She becomes a wolf-woman, then holds a conversation with invisible others in which the words escape into themselves, as if holding their contours within the world of sound without symbolic function. You could say she sounds like a bird but birds exist in their own universe. A video on YouTube – Signs of Voices – shows her stroking the fur (made from paper) of an improbably long animal, singing in a whisper as if speaking directly to its unknown consciousness. There’s a relationship to ASMR, reflected in the YouTube comments, but unlike ASMR, which hovers in an intensely private/public space, her voice addresses itself to space itself, and whatever inhabits space (as if a bat locating otherwise invisible moths by the energy of directional sound).

As the set at Iklectik progresses her vocal techniques become more familiar – some ultra-low vocal fry, Mongolian and Tuvan style chord singing, whistling with added melody – but the way she uses them is otherwordly, as if she is experimenting with non-human identities. She strikes her chest, as if shaking loose a sound from its resonating cavity. Of course I’m reminded of other great improvising singers – Elaine Mitchener, Ami Yoshida, Sidsel Endresen, Sharon Gal, Phil Minton, Shelley Hirsch, Sofia Jernberg, Yifeat Ziv and more – but her demeanour is so calm. No visible wrestling with the emotional/physical effort of extreme voice production; just emanation, as if by a charm.

Ami Yamasaki and Charlie Collins performed at Iklectik creative space, London, SE1 7LG, 17.11.2019, alongside O Yama O, Beatrix Ward-Fernandez, Derek Saw and Lauren Sarah Hayes.

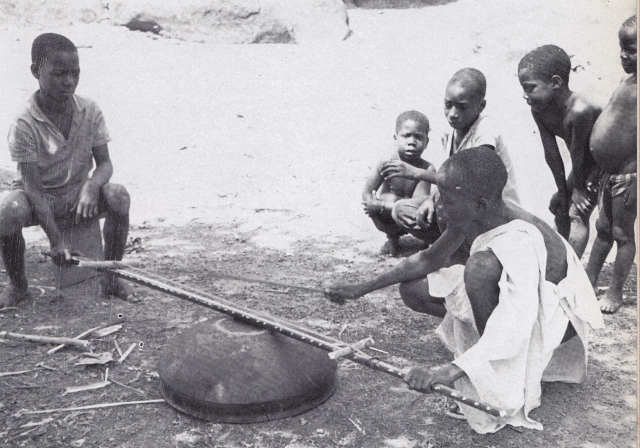

Maybe a coincidence but during our Sharpen Your Needles event last night (28.09.17) Evan Parker played “Music for Mbale (Ndokpa)”, from The Photographs of Charles Duvelle: Disques Ocora and Collection Prophet, a sumptuous book and two CDs published by Sublime Frequencies. Recorded by Duvelle in Ngouli, Central African Republic, in 1962, the instrument played by two men for the Mbale village festival was a lingassio, a four key xylophone mounted over a pit.

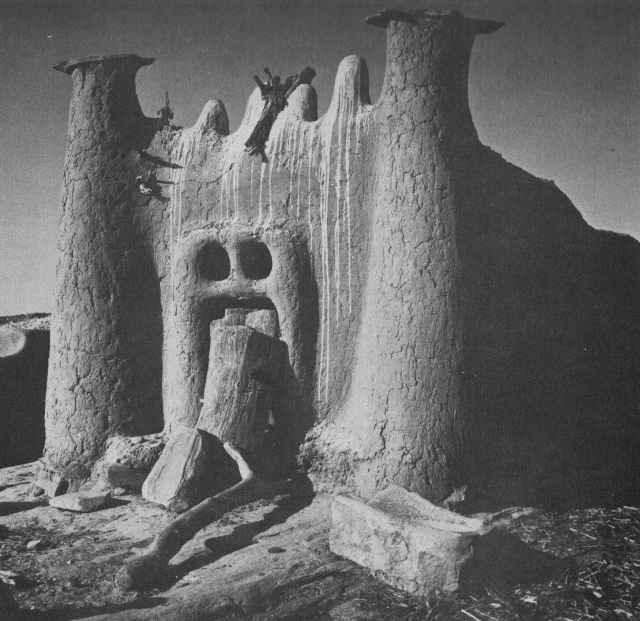

Maybe a coincidence but during our Sharpen Your Needles event last night (28.09.17) Evan Parker played “Music for Mbale (Ndokpa)”, from The Photographs of Charles Duvelle: Disques Ocora and Collection Prophet, a sumptuous book and two CDs published by Sublime Frequencies. Recorded by Duvelle in Ngouli, Central African Republic, in 1962, the instrument played by two men for the Mbale village festival was a lingassio, a four key xylophone mounted over a pit. One lesson to be learned from this is not to jump to easy conclusions about earth instruments and primitivism. The Dan had other ways of amplifying sound, as the above photograph shows, but terra-technology floated somewhere out on the edges of society, either marginal, in the sense of being a diversion for the melancholy and immature, or spectral, as sound masks emitting the voice of a supernatural being. When I was beginning to research non-western music in the early 1970s unilinear cultural evolutionism was still prevalent. To find any subtlety in the literature you had to read ethnomusicologists like Klaus P. Wachsmann (father of improvising violinist Philipp Wachsmann). In my early twenties I was excited to read his chapter – The Primitive Musical Instruments – in Musical Instruments Through the Ages (edited by Anthony Baines, 1961). “While considering them,” he wrote, “it must be borne in mind that the effectiveness of a musical instrument can only be measured by the degree of satisfaction its sound gives to the people who use it.” He devotes a short section to what he called Ground Instruments: ground zithers, percussion beams, stamping pits, ground bows and, most fascinating of all: “In Abyssinia a narrow, tapering hole is made in the ground and howled into; the vernacular name of this instrument means ‘lion’s call’.”

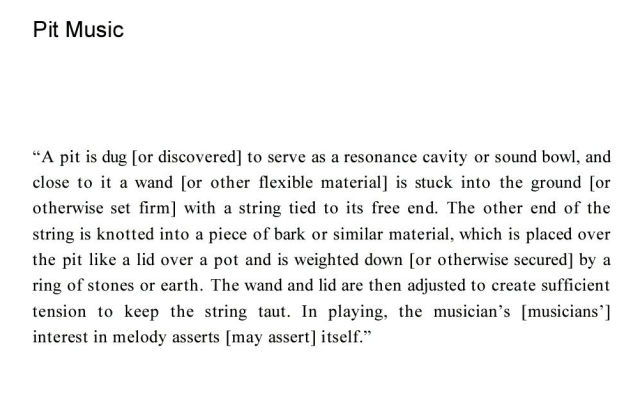

One lesson to be learned from this is not to jump to easy conclusions about earth instruments and primitivism. The Dan had other ways of amplifying sound, as the above photograph shows, but terra-technology floated somewhere out on the edges of society, either marginal, in the sense of being a diversion for the melancholy and immature, or spectral, as sound masks emitting the voice of a supernatural being. When I was beginning to research non-western music in the early 1970s unilinear cultural evolutionism was still prevalent. To find any subtlety in the literature you had to read ethnomusicologists like Klaus P. Wachsmann (father of improvising violinist Philipp Wachsmann). In my early twenties I was excited to read his chapter – The Primitive Musical Instruments – in Musical Instruments Through the Ages (edited by Anthony Baines, 1961). “While considering them,” he wrote, “it must be borne in mind that the effectiveness of a musical instrument can only be measured by the degree of satisfaction its sound gives to the people who use it.” He devotes a short section to what he called Ground Instruments: ground zithers, percussion beams, stamping pits, ground bows and, most fascinating of all: “In Abyssinia a narrow, tapering hole is made in the ground and howled into; the vernacular name of this instrument means ‘lion’s call’.” The allure of such an instrument, hole within a hole, absence within absence, Is out of all proportion to its simplicity. One contribution to the above mentioned social media thread came from Ilan Volkov, who drew my attention to Christian Wolff’s Pit Music (1971), published in Prose Collection. The piece could easily be a description of how to make your own version of the Dan earth bow, though that seems unlikely as both Zemp’s book and Wolff’s composition emerged in the same year. As Ilan pointed out, Wolff never intended his Pit to be actually made. Like a lot of things, post-Fluxus, it was an indication of potential (political as much as anything) rather than an imperative. I wrote similarly provisional pieces a few years later, the Wasp Flute that was never put into practice even though the instrument was built, and hypothetical events in which I performed with seals and fish, all of them suggestions of how life might be lived in a world less traumatised by what Timothy Morton has called The Severing (in his new book, Humankind: Solidarity with Nonhuman People).

The allure of such an instrument, hole within a hole, absence within absence, Is out of all proportion to its simplicity. One contribution to the above mentioned social media thread came from Ilan Volkov, who drew my attention to Christian Wolff’s Pit Music (1971), published in Prose Collection. The piece could easily be a description of how to make your own version of the Dan earth bow, though that seems unlikely as both Zemp’s book and Wolff’s composition emerged in the same year. As Ilan pointed out, Wolff never intended his Pit to be actually made. Like a lot of things, post-Fluxus, it was an indication of potential (political as much as anything) rather than an imperative. I wrote similarly provisional pieces a few years later, the Wasp Flute that was never put into practice even though the instrument was built, and hypothetical events in which I performed with seals and fish, all of them suggestions of how life might be lived in a world less traumatised by what Timothy Morton has called The Severing (in his new book, Humankind: Solidarity with Nonhuman People).

While eating shojin ryori cuisine outdoors at Izusen, Daitokuji temple, Kyoto, in spring sunshine, April past, I reflected on François Jullien’s In Praise of Blandness, the appreciation of blandness or insipidity in ancient Chinese aesthetics and ritual practices. Commenting on a text describing the use of muted music during ritual offerings to the ancestors he says this: “For the most beautiful music – the music that affects us most profoundly – does not . . . consist of the fullest possible exploitation of all the different tones. The most intensive sound is not the most intense: by overwhelming our senses, by manifesting itself exclusively and fully as a sensual phenomenon, sound delivered to its fullest extent leaves us nothing to look forward to. Our very being thus finds itself filled to the brim. In contrast, the least fully rendered sounds are the most promising, in that they have not been fully expressed, externalized, by the instrument in question, whether zither string or voice.

While eating shojin ryori cuisine outdoors at Izusen, Daitokuji temple, Kyoto, in spring sunshine, April past, I reflected on François Jullien’s In Praise of Blandness, the appreciation of blandness or insipidity in ancient Chinese aesthetics and ritual practices. Commenting on a text describing the use of muted music during ritual offerings to the ancestors he says this: “For the most beautiful music – the music that affects us most profoundly – does not . . . consist of the fullest possible exploitation of all the different tones. The most intensive sound is not the most intense: by overwhelming our senses, by manifesting itself exclusively and fully as a sensual phenomenon, sound delivered to its fullest extent leaves us nothing to look forward to. Our very being thus finds itself filled to the brim. In contrast, the least fully rendered sounds are the most promising, in that they have not been fully expressed, externalized, by the instrument in question, whether zither string or voice.