Glenn Hendler is a professor of English and American studies at Fordham University and author of the just-published 33 1/3rd book on Bowie’s Diamond Dogs. This is the second book in the 33 1/3rd series on Bowie’s albums—the previous one is Hugo Wilcken’s Low, now nearly 15 years old (!).

Given that Glenn’s book promotion was hit by the ongoing pandemic nightmare, I wanted to interview him in depth to give you a sense of what his study of Diamond Dogs is about. You can buy the book directly from his publisher here. He and I exchanged a series of emails in early April, which I’ve edited into the following conversation. Hope you enjoy.

CO: Let’s start with the writing of the book. When did you pitch the idea to 33 1/3rd, and was Diamond Dogs always the LP you wanted to do? It’s the first in the series since Wilcken’s Low. One might have thought that 33 1/3rd would have gone with a warhorse like Ziggy or Scary Monsters as the next Bowie volume, so I was delighted when I saw they’d picked you.

Glenn Hendler: At least since I became someone who writes about culture—studying film history and theory as an undergrad, going to grad school and becoming an English professor—I’ve long fantasized about writing about David Bowie. Decades ago, I even sketched out an article about Lou Reed and Bowie, and their related but different ways of addressing their listeners (probably the only thing it would have had in common with the DD book is that it would have included the word “interpellation”). Somewhat more recently, I jotted down some notes about an article I wanted to write about singing “Kooks” to my kid from the time he was a few days old (I still do, most nights). But I kept writing about the 19th Century, which wasn’t going to lead me back to David Bowie.

Then two things happened. By sheer coincidence, I ended up sitting next to then-33 1/3 editor Ally-Jane Grossan on a plane, noticed that she was reading interesting-looking things about music, and engaged her in conversation. She asked—as I’m sure 33 1/3 editors always do when they encounter a chatty fan of the series!—what album I’d want to write about. I said that while the most obvious album would be Ziggy Stardust, I might have more to say about Diamond Dogs…and that there were lots of other options, too! She was politely encouraging, said there was only the one Bowie book in the series and they’d be open to doing another if the proposal grabbed their interest.

I kept that idea percolating for a long time. Then Bowie died, I took those notes about “Kooks,” and—very quickly, especially for an academic—pulled together an article that was published on the Avidly blog of the Los Angeles Review of Books. That got some positive responses…including from one of the then-new four-member editorial team at 33 1/3, Kevin Dettmar (who also wrote the volume on Gang of Four’s Entertainment). I just submitted a proposal in response to an open call, and was thrilled that it was accepted.

CO: So, our first hearings of Diamond Dogs are rather different. You first hear it in 1974, at age 12, which seems like the perfect age! I was 18, in late 1990, buying the Ryko CD reissues in rough release order.

And I didn’t really like Diamond Dogs. I listened to it the least of the batch between Man Who Sold and Station. I’m trying to recall why. Something about it bugged me then—the “cabaret” songs like “Sweet Thing” and “We Are the Dead” didn’t connect at all and I even found them grating. I was into “Big Brother” and “1984” (in part because I already knew them from the Sound + Vision comp) and “Rebel Rebel” was, of course, the hit—the only song you’d hear on Connecticut classic rock radio then. Whereas you describe DD as “the first album that challenged me to study it.” Did it hook you immediately, or was there a period similar to mine where you had to really work to get into it? I feel like I failed the test, back then.

GH: So you grew up in Connecticut, too? When you say, “Connecticut classic rock radio,” I think WPLR—is that right? That’s what I grew up listening to…though my first radio listening came before FM had really caught on, and everyone listened to Top 40 AM radio because you didn’t have a choice.

CO: WPLR, yes, but more WCCC and WHCN, which were the two classic rock monoliths of the late 1980s in Connecticut. These were very canonical-minded—would often do Top 250 Best Rock Songs Ever Blah Blah weekends, etc. (“Stairway to Heaven” always #1). My best friend and I would call them up and ask them to play Husker Du or Fishbone & the DJs would get mad (“that’s not a real group, stop messing around” one said).

GH: I remember WHCN, vaguely. My Bowie listening started when he was mostly just not on the radio at all, at least not the radio I heard. It was totally word of mouth and all about who bought vinyl albums. I remember playing not Diamond Dogs but David Live; that was my real first exposure. It was the guitar on David Live that hooked me first (at the same time, I got into Lou Reed because of Rock ‘n’ Roll Animal; I can still reproduce in my head every note of the long guitar duet at the beginning of “Sweet Jane” on that album).

It was right about then that I got my first stereo and record player, and gave my parents a list of records to get me for my birthday. From that list I got most of the early Bowie albums. I think I liked Man Who Sold the World first—more macho guitars—and a lot of Aladdin Sane. For the same reasons I liked the guitar-heavy songs on the other albums, such as “Suffragette City” and “Ziggy Stardust.” As an indication, the other albums on that initial list included the first two by Bachman-Turner Overdrive (lots of crunching guitar chords; I heard them as similar to “Ziggy Stardust”). Plus: Elton John, who at first vied with Bowie for my affections. I got Caribou and Goodbye Yellow Brick Road. There was some hard guitar there (“Saturday Night’s All Right for Fighting”), but Bowie and Elton John both mixed the guitar rock with more piano-based, cabaret-like songs, and I guess that combination stuck with me.

While Diamond Dogs wasn’t the one that hooked me first, at the same time—for those last reasons—I didn’t find the non-rock stuff grating. In fact, because my first exposure was to David Live, and that documented the Diamond Dogs tour, there were more familiar songs on DD than on any other album. I suspect, in retrospect, that it mattered that the David Live version of “Sweet Thing” was more guitar-centric than the original on the album. But—as the book explains—I was really into the lyrics, and that’s what at first challenged me. It just annoyed me that there was no lyric sheet, and so I wanted to figure them out. That led to me listening to the songs with headphones on, over and over, putting the needle back over and over again till I got what I thought were the right lyrics. Since I found myself doing the same thing with headphones on decades later when I was writing the book, it really brought that time back.

CO: The book opens with the 1980 Floor Show, which remains among the more bizarre things Bowie ever did. You describe Diamond Dogs as an album of transition: would you agree that the Floor Show is the true prelude to it?

Because the Floor Show jumbles everything: the Marquee Club (where DB had a “residency” as a Mod in the ‘60s), Mick Ronson, Marianne Faithfull, the Astronettes, Ziggy, with “1984/Dodo” as a warning sign to fans of what was coming next. Is there a premonition in how Bowie’s tearing down and churning up the past here? And it’s so wonderfully garish and ugly—the lighting is school-theatre quality at times. Did you have the Floor Show as the opening from early on, in the writing of the book?

GH: Yes, from early on. It was such a formative moment for me as a kid, seeing it on TV [it first aired in the US in November 1973 on The Midnight Special]. If anything in the book I understate how much that blew me away, and how much it stuck in my mind for all the decades between the one time I saw it and when finally YouTube came along and I could see bits of it again. I had trouble figuring out how to frame the book with it (especially when I realized I’d seen it in 1974, on its rebroadcast, which kind of ruined the idea that I was among the first to see Bowie on TV in the US).

It was also pretty clear to me that I could use The 1980 Floor Show as a way of concisely getting Bowie’s history before Diamond Dogs into the book. I couldn’t assume that readers knew all that, after all. I think you’re exactly right when you say Bowie was “tearing down and churning up the past” in that show: his own past, the history of rock and pop music, everything. The Troggs represented one weird version of the past (and also stood in a way for Iggy Pop and Bowie’s own (re)discovery of the primitivism of rock music); the songs from Pin Ups on the show represented another. Carmen—I want to research and write more about Carmen! I consulted with some of the major experts on rock and Spanish-language music in Los Angeles, and none of them knew anything about Carmen!—seemed to point toward a future. There’s so much more to be written about that show, and Amanda Lear, and Bowie’s recurring interest in Octobriana, and all the things converging at that moment. The photo book about that show came out as I was writing, and I came across Madeline Bocaro’s really useful blog…but there’s still more to be said.

CO: I forgot about Carmen! And yes, Lear and Octobriana. What could’ve been. Bowie is churning up so much stuff in those months after the last Ziggy show. He’s both liberated and I think rather terrified—he’s ended the thing that’s finally gotten him famous, and only after a year or so. So ‘where to go next?’ consumes him in late 1973. Managing the Astronettes and working with Lulu (at the exact same time he’s making Diamond Dogs!—it’s understandable his coke period reportedly starts around now) suggests he still thought he’d be a songwriter/producer for other acts, too, as a sideline to occupy him if his other projects bombed out.

GH: Yet another never-written chapter would have been about The Astronettes, and had a lot about Ava Cherry as his connection to black music. If my book release party had actually happened—just one week earlier and we wouldn’t have been under quarantine (though I fear we instead would have been unknowingly spreading the virus!), one of the singers was going to be Raquel Cion, who does a Bowie Tribute show called Me and Mr. Jones. Raquel actually knows Ava Cherry—I’d like to have developed that connection and found out some stuff from her! Anyway, I think that’s a good reading of Bowie’s state at this point; liberated but directionless and a little panicked.

Oh, and one other thing: The 1980 Floor Show was a useful way for me to foreground my status as an American writer writing about an artist who was still very British. And to do so unapologetically. It allowed me, essentially, to argue that while the earlier albums had been for a UK audience, at the time of Diamond Dogs Bowie was now playing for me.

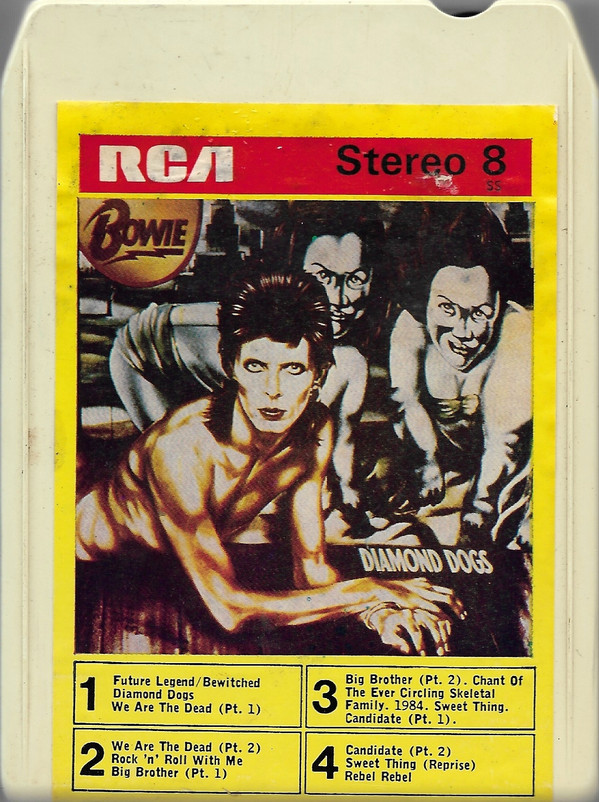

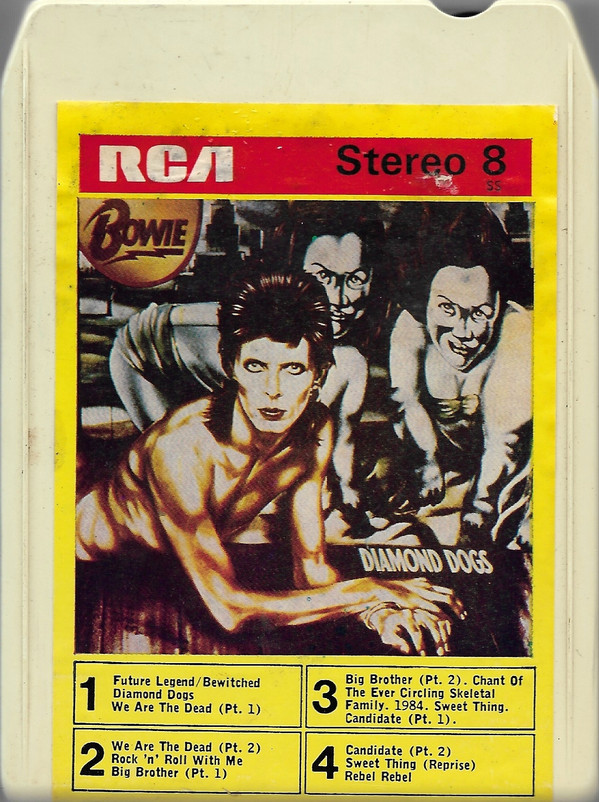

CO: I find Diamond Dogs being a UK #1 album fascinating, because it shows how Ziggymania was still red-hot there and how different the cross-Atlantic markets were for Bowie in the 70s. Bowie doesn’t really start moving LPs in the US in substantial numbers until Young Americans.

GH: Yes—another thing cut from the book was a lengthy piece on the difference between the UK and US audiences, including the way radio worked. All that remained was the thread that was about him trying to make it in America in different ways, and that’s pretty undeniable. I am guessing that my rather jaundiced view of the song “Diamond Dogs”—even though it matches Charles Shaar Murray’s—is the thing in my book that would most distress many UK readers, since that song was a pretty big hit there. I’ve always wondered how the world would be different if Bowie had released either “1984” or even “Rock ‘n’ Roll with Me” as the follow-up single to “Rebel Rebel.” Would he have moved from the AOR niche he carved out with “Rebel Rebel” onto black (or rather interracial) radio earlier, before “Fame”? Would “Rock ‘n’ Roll with Me” have put him in competition with Elton John for the piano ballad mainstream? It really is an Elton John song in some ways. “Diamond Dogs” was just a terrible choice for a second single.

CO: I liked your argument that while Diamond Dogs has three main tributaries—-the stillborn George Orwell adaptation, a Ziggy Stardust cut-up musical, and the William Burroughs’ Wild Boys-inspired Hunger City/Halloween Jack stuff—there’s so much more blurring and interweaving between the concepts within the individual songs. Looking back, I think I pushed the “three albums” idea too hard—I now see DD’s far more of a conceptually murky album than I first considered. Is the power of DD in part because it’s so difficult to get a sense of where Bowie’s coming from?

GH: All I can say to this is “yes.” I think this was the aspect of my book that could have most easily been framed as building on you but also arguing with you—but also with so much other writing about Diamond Dogs that splits it up into parts. And yes, that’s the challenge of the album. I think it’s both more “murky” and more cohesive than it’s been made out to be. I know there’s always a risk of a critic imagining more cohesiveness in the object of analysis than the artist ever imagined, and so I’m sure that some of what I’m doing in the book is making it more cohesive. But even if that’s so, I think that in a way hearing it as more cohesive makes it more interesting to listen to.

CO: You note how the Diamond Dogs lyrics are often an “I” character that’s addressing a “you,” and that this sort of design isn’t in the service of love songs but more, as you say, along the lines of a policeman yelling “hey, you!” to someone on the street. Was this something you noticed while writing, or had this been something you’d been aware of as a listener, years before? I thought it was an insightful observation. Is there a sense that the whole album is a dialogue between DB and his fans, in this cracked way?

GH: Definitely. If you’ve gotten to what I say about “Rock ‘n’ Roll With Me” (a song that I always found kind of dull, but came to see as a major part of the record), I think Bowie is kind of explicit about that. I don’t actually think the I/you structure is that unusual for Bowie; I think that’s something he used—selectively but importantly—throughout his career. (That’s what my “Kooks” piece is about, too.) And I think he often thinks about his relationship with his fans. I mean, the whole plot (such as it is) of Ziggy is imagining himself into a character who’s literally torn apart by his fans’ fanaticism. That he wrote and performed this before he really had many fans—that he made it come true through his own performance of it—is part of his brilliance. And that he could make fans (including me) feel that Blackstar was a parting gift to his fans (aren’t those Tony Visconti’s words?) without, this time, actually thematizing his fans (except, a little, in “I Can’t Give Everything Away”) is a sign, to me, that thinking about the performer/fan relation was one of the projects of his career.

From the Terry O’Neill photo session, 30 January 1974

CO: I’ve called this record “diseased” and “rotten”-sounding before, which you seem to agree with. What do you suppose creates this kind of aural sensation? The distorted instruments? The use of doubling (the bass/harpsichord figures that you mention in “1984”)? Bowie’s scrungy lead guitar lines? The sort of seemingly rough edits in “Big Brother,” as you note? In line with how Bowie was ripping off the Stones openly on the title track and “Rebel Rebel,” I now wonder if it was his take on the sound of Exile on Main St.

GH: I do agree, so long as you meant “diseased” and “rotten” in a good way! And yes, all those factors play into the rottenness it conveys. I’d love to have a conversation with Tony Visconti sometime about what it was like to mix that album. He talks in his book about the brilliant work Bowie had already done in the studio, but it’s also clear that the tapes Bowie brought him were kind of a mess, and I suspect that some of the decisions he made (to accentuate the distortion) probably cover over some badly recorded or deteriorated tracks. And yes, I think the doubling of sounds, and of vocals, is crucial, not just for the general creepiness it produces, but that it also fits the paranoid themes of 1984. I think I say at one point that the second vocal track in “We Are the Dead” is like the state or the Party always watching, always knowing what was happening. [And on ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll With Me’: “You (the Party) always were the one that knew.”] I’m not even sure I quite believe, myself, the claim that the pre-echo of the piano line in that song deliberately refers to that aspect of 1984, but I think it works that way, that it has that effect.

CO: While I haven’t been much of a fan of the new mixes of DB’s old albums, I wouldn’t mind hearing substantially different versions of Diamond Dogs tracks. Feels like there’s so much buried—I wouldn’t be surprised if there were all sorts of backing vocals, saxophone, Mellotron lines that were turfed in the final mix.

GH: Even the minor remixing that’s reproduced in the Who Can I Be Now? collection that I now listen to the most—because I like The Gouster better than Young Americans—clarifies some instruments. The acoustic guitar strumming under “Rebel Rebel,” for instance. My sense is that Mike Garson is the player who lost the most due to the muddy mix on Diamond Dogs. When his piano emerges from the muck for a few moments, it’s either a gorgeous set of chords, as in “Sweet Thing,” or furiously wild playing that does not deserve to be way in the background, as in “Candidate.” I wonder, though, if a better mix might oddly decouple some of the instruments that are so closely mixed that you can’t hear them separately, like the two instruments locked together in “1984,” or whatever interlocked combination of Mellotron and guitar that is playing in “Chant” (I have little idea what the main instruments are there!).

And yes, there’s more to say about the Stones and the “anxiety of influence,” as (if I recall correctly) you call it. I can’t recall if it got into the book or was cut, but I read “Diamond Dogs” itself (the one song on the album I’ve never liked) as Bowie’s effort to create the kind of loose rock band sound that is epitomized on Exile on Main Street, but to do so by splicing a lot of tapes together rather than by gathering a band together in a big old house and recording the jamming together. That’s part of what’s so interesting about the album, is how Bowie hit a set of paradoxes here. Rather than trying to solve the tension between the ideology of authenticity that Simon Reynolds talks about in the 1960s, and the obsessive constructedness that was his method, he just stages that as a contradiction on the album, in song after song.

CO: That’s a great point. Using a clip of a live Faces recording to kick off the album is part of that, too. “Sampling” rock ‘n’ roll in a way, making his own weird model kit version of it—akin to all the scale models and video clips he was making of Hunger City at the time.

GH: Looking at it that way, it makes perfect sense that he’d go from this to an immersion in the Gamble and Huff Philly sound, and soul music in general, because in that context, there just is no contradiction between authenticity and expressiveness, on the one hand, and a well-constructed and crafted studio album, on the other. I feel like those videos of him orchestrating the intricate call-and-response of “Right,” and then leaning back with a smile as Luther Vandross et al just do it, with feeling, show an artist who has come to a completely different resolution to the conflicts staged in the making of Diamond Dogs. Does that make sense?

CO: Yeah, the usual 180 degree move for Bowie? Young Americans is meant to be communal, live, made “on location” with American Latino and black musicians, with his fans camped right outside the studio while he works (though of course he tinkers with the tapes as much as he did on Diamond Dogs). Tin Machine, 15 years later, is another variation on this.

GH: It is a 180 degree turn in a way, but I think I read it more as a resolution to the problems he staged (fascinatingly) but couldn’t solve on Diamond Dogs. To get a bunch of musicians to work intimately together, but then to work with the tapes and do complex things in the production and mixing process, was not to do two antithetical things in the Gamble & Huff world; that’s just how the music industry worked. It’s only in the rockist (to use a word that wouldn’t have been used at the time) world shaped by people like the Rolling Stones that this would seem like a real problem. I think it’s all tied to Bowie’s shifting understanding of black American culture. The rock version of the ideology of authenticity—which (pace Simon Reynolds) he was still tied to even after the glam years, had to do with the white British vision of a cultural authenticity grounded in the blues. When Bowie started listening to soul and early disco, and the sound of Philadelphia, that kind of gritty authenticity started to seem irrelevant, and studio manipulation wasn’t in tension with spontaneity any more.

CO: The use of stasis and repetition often gets overlooked on DD: I liked how you showed what “Rebel Rebel” owes to this, how “Rock ‘n’ Roll With Me” becomes a loop of refrains halfway through. But I’m intrigued by how you came to decide Steve Reich was an influence on “Chant of the Ever Circling Skeletal Family”—I’d thought that was probably too early, but you make a very good case for it (also congrats on nailing the time signatures of that track better than anyone I’ve read—it’s a nightmare!) [I’m not going to spoil it—buy the book.]

GH: That part of the book was me just asking lots of smart people what they thought, and pulling together what they said until I had a synthesis that I thought was right. I put out a general call on Facebook to listen to “Chant” and help figure out the time signature; I asked colleagues in the music department here. And I got lots of technical and other advice that I incorporated.

I started trying to figure out the time signature of “Chant” when I was about 16 or 17. I was at a boarding school in Connecticut, and generally very unhappy there as a semi-local surrounded by rich kids. But my senior year there I got as a roommate a guy named Matt Brubeck, son of Dave Brubeck. He taught me to appreciate a much wider range of music (including jazz, which up to that point I hadn’t listened to, but when you’re spending weekends at the Brubeck home and going to his concerts, you learn to appreciate it). I also tried to convince Dave to appreciate Bowie, without a lot of success. He was an avid listener to all music, so he was patient. The one song he was fascinated by, as I recall, was “Sons of the Silent Age.” Make of that what you will.

At any rate, Matt and I would sit and figure out time signatures of rock and jazz tunes, and specialized in identifying rock songs that were other than 4/4. It’s the only musical concept that I’ve ever really internalized. And I remember sitting with Matt and trying to figure out “Chant,” to no avail. It stumped even him at the time. (I don’t think we ever played that for Dave; I wish we had).

CO: Oh, the idea of Brubeck covering “Chant.”

GH: Anyway, almost 40 years later, when writing the book, I got in touch with Matt and asked him to listen to it again. In the meantime, he’s gotten a Ph.D. in musicology; he is on the faculty at York University in Canada. He’s the one who first suggested Steve Reich-influenced phasing on the song, explained to me how it might work, and pointed me to some basic readings that would help me understand it. (Coincidentally, I also went to hear some Reich performed live at about this time). I took what he told me, wrote it out in a way I could understand it, and sent it back to him; he made a couple of suggestions and corrections, and said he thought I’d got it right. A few of the other people who’d commented on Facebook also agreed. So that’s how I got there—using other people’s brains and knowledge! What I don’t have is a smoking gun, something showing that Bowie was aware of the phasing technique. But there’s Reich music using that technique that Bowie could easily have heard. Here’s another place where I think talking with Tony Visconti could be useful; I bet he’d know more about how that song was put together.

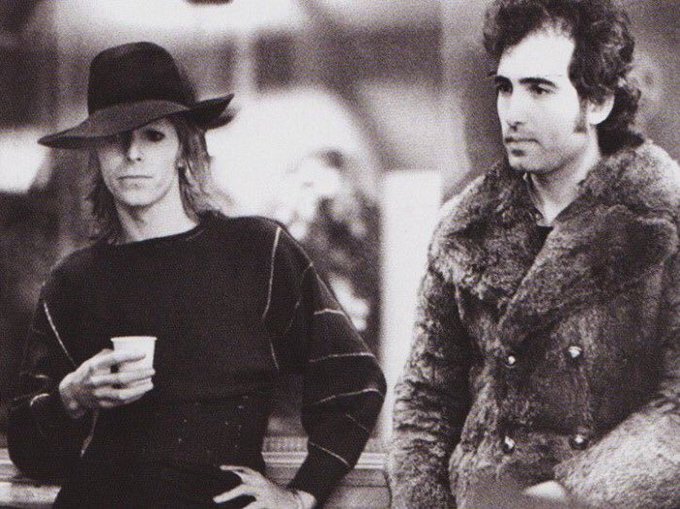

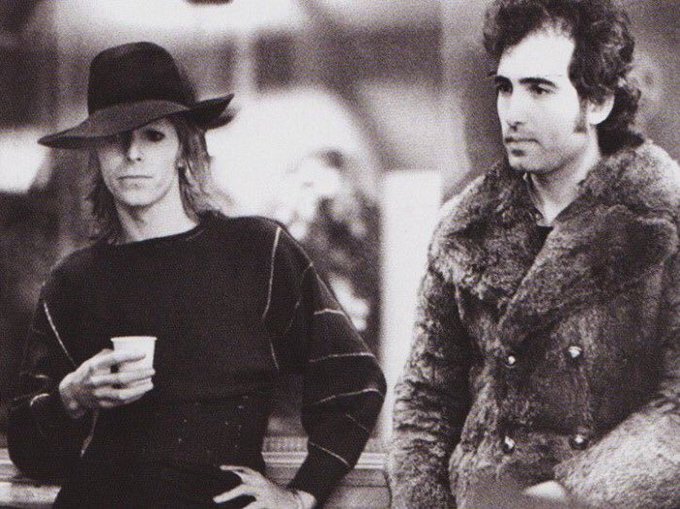

Bowie and Garson at Olympic Studios, 14 January 1974 (Kate Simon)

CO: When you were revisiting DD for the book, did you revise any opinions you’d long had about it? Did you listen to it in a different way? One trick I used when I was doing my thing was to completely rearrange LP sequences to try to hear them fresh—I often listened to The Next Day in its recording order; same with Blackstar. Curious if you did something similar.

GH: I’ve already mentioned that I never thought much of “Rock ‘n’ Roll With Me.” In writing the book, I came to appreciate what he’s doing there (and to like some live versions of it much better than the original; the backing vocalists produce much more dynamism in relation to the song’s repetition). I didn’t so much listen to the songs in a different order, as you did. Mostly I listened to them in isolation from one another, and wrote about them separately. I also initially wrote about them in order, which resulted in a manuscript about twice as long as what Bloomsbury wanted. They assigned me a content editor, who bluntly, though politely, told me what I should have already known: that 33 1/3 books that go in order, track-by-track, rarely work. So she helped me reorder the chapters, which made it much easier to pare down the length. Sometimes when I reread it I think the order works really well; sometimes it seems a little random to me. But I am reasonably confident that it’s much better now that there aren’t 100 continuous pages about “Sweet Thing/Candidate/Sweet Thing (reprise)” (OK, slight exaggeration), and that I deal with different aspects of that—my favorite Bowie piece ever—in different places in the book.

I had thoughts of using Raymond Williams’s keywords idea to organize my Bowie book, since I’ve spent the past decade-plus coediting Keywords books. But then Kevin Dettmar did that for his Gang of Four book. I do think a Keywords for David Bowie would be pretty fun to put together.

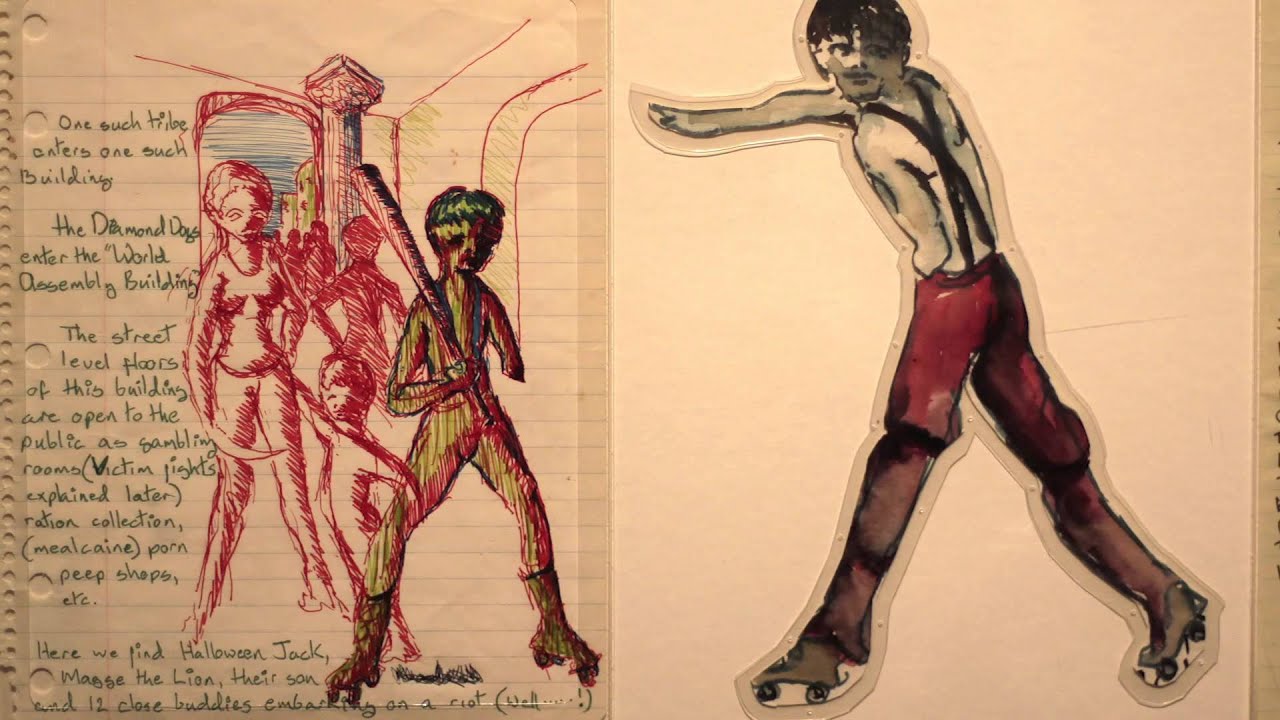

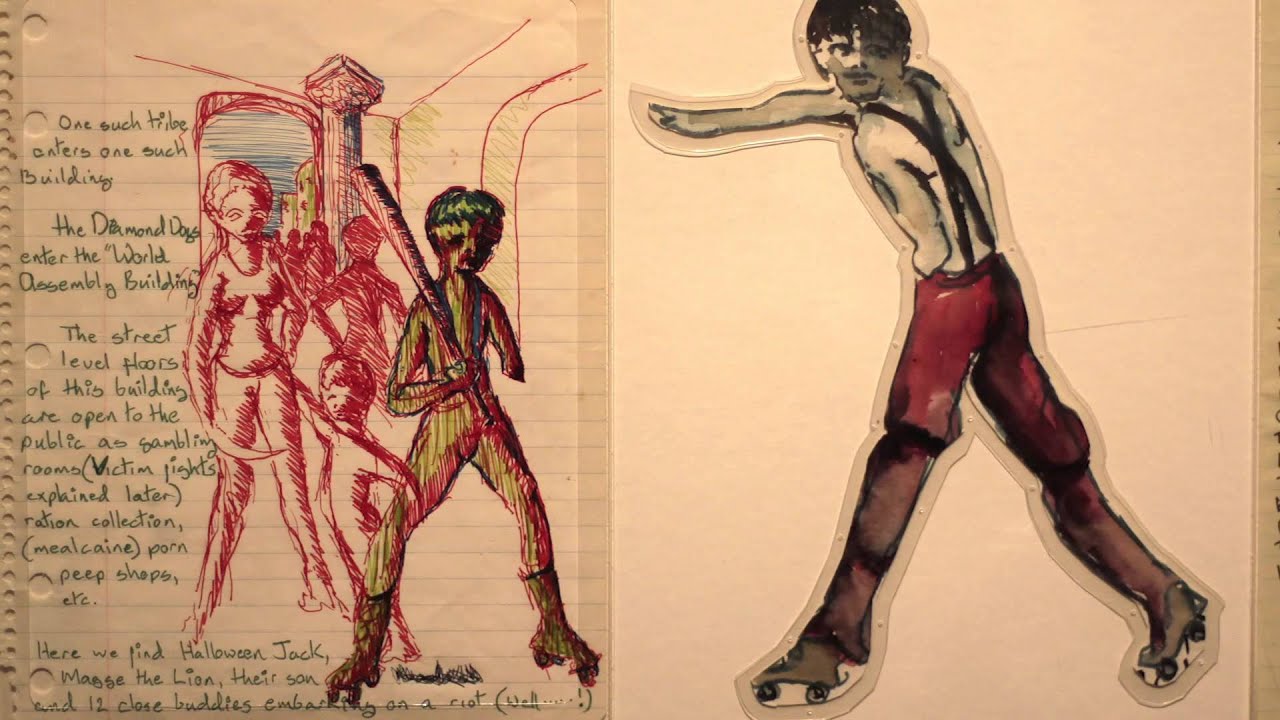

CO: There wasn’t much in the book on DB’s sketches/video ideas for the album (like the Diamond Dogs living on “mealcaine” and the other bizarro stuff from sketches in the museum exhibit). At some point in the writing were you devoting more space to that angle (“the mutant crap” as John Lennon once called it)? Or were you always focusing more strictly on the music/lyrical interpretations, and found such material to be superfluous?

GH: I’d intended to write more about that stuff when I planned the book, but then (as mentioned) wrote twice as much as 33 1/3 needed, just writing about the music and lyrics. Part of the reason is that I never got into the Bowie archive (despite corresponding with the two curators of David Bowie Is, who were supportive and helpful), and in any event I realized early on that my contribution here was going to be primarily interpretive, not archival. So no, I didn’t think it would be superfluous; I just didn’t take the time and didn’t have the space. I think a whole book could be written on the Diamond Dogs tour, including Bowie’s imagination of the film, how that translated into sets, etc. And that book should probably get going before more of the people involved pass away. There’s so much interesting stuff to be said, and in the course of my initial research I came across some stuff that’s never been in any of the biographies….but I decided that this book had to be just about the album. Even the 1980 Floor Show opening almost had to be cut for space…but I still thought the reader needed a way in, that reading a claustrophobic book about a claustrophobic album wouldn’t be a pleasant experience!

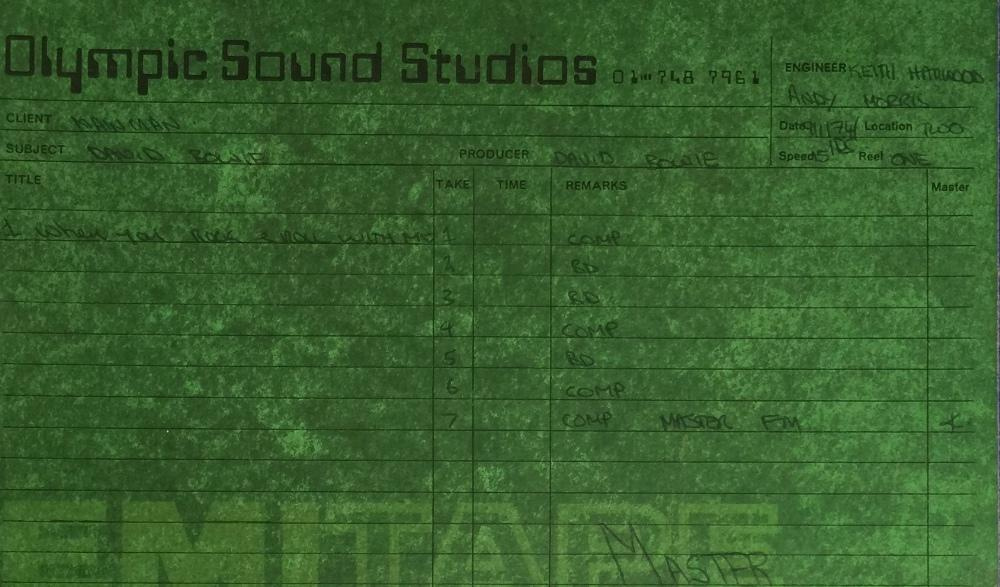

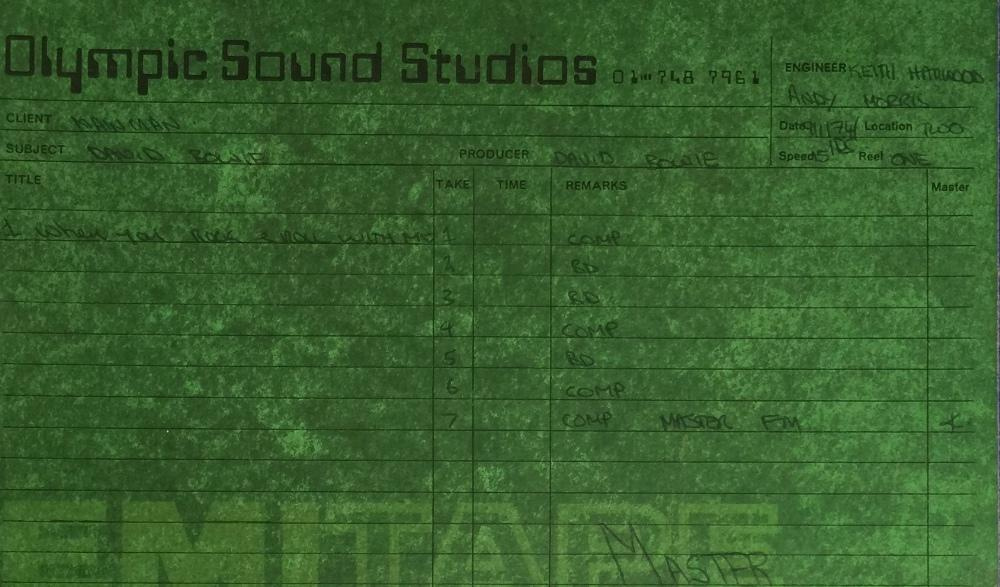

CO: Did you hear the studio tape that just leaked of Bowie going through five or so takes of “Rock ‘n’ Roll With Me”? I found it charming and it made me like the song a bit more.

[Glenn had not, and listened to the tape.] It is charming, indeed. That’s got to be Garson on piano, right? “Keep it clean, Mike”—trying to get him not to do his trills and frills that he loves so much. It’s so interesting, if this song was early (from the supposed Ziggy musical) that it was still not fully formed at this late date. But “I would take invaders into hand/while tens of millions failed to understand”—those lyrics make more sense in a Ziggy context, not so much in DD. And the shift from “tens of millions” to “tens of thousands” takes it from a global scale to the audience that might be present at a concert. I wonder when he changed the first word from “I” to “you.” That shift almost doesn’t matter: the “I” and the “you” are crucial, by my argument, but also often interchangeable. “Rental heats are counted down?” Yikes.

I guess what’s most striking is the lack of guitar. I wonder if he always intended to add it, or if he meant Garson’s piano to be the lead instrument. I’ve always wondered if Bowie played it himself (as the album credits would indicate) or if it’s another uncredited Alan Parker performance (as in “Rebel Rebel”). From just a few bars in, when the guitar should come in, to the final chords—which were clearly always part of the song but sound so weird just on piano, especially with a Garson trill at the end, as he keeps insisting on doing. Fascinating. Thanks for pointing it out to me.

CO: You didn’t go much into “Alternative Candidate,” the joker in a rigged pack of cards. When I wrote about it for the book, I found it exhausting to interpret—how does it fit in? Was it supposed to, ever? It’s the mystery at the heart of the album sessions for me. Curious if your thoughts on it wound up getting cut for space, since it’s not part of the proper album, or if you hit a similar wall.

GH: Everyone always asks me about “Alternative Candidate.” Someday I’ll have to figure out something to say about it. I never came up with any insights. I am fascinated by its existence, and its small lyrical links to “Candidate,” but I find the teenage boy/mountain-teenage girl/fountain opening just embarrassing, and think that while there are some cool lines (I like the three “I make it a thing” lines, for instance) and as you say in the blog, there are little fragments that either indicate Bowie’s obsessions of the time (the Fuhrerling is a fascinating word. So is the mention of Brylcreem) or would turn up later in other songs. Did you ever hear the unreleased Elvis Costello song “Seconds of Pleasure?” It’s this kind of storehouse of lyrics that later appear in other songs. Seems similar to me. The piano line is interesting—kind of boppy, but a bit ominous at the same time; I can see how he’d want to do something with it.

Ultimately, then, after that free associating, the answer is that I wrote more about the album as I heard it in 1974-5, so no “bonus tracks” come up, as far as I can recall. This is another difference I made consciously from what you did in your book (not to try to be better, but to be different). Yours is structured by Bowie’s creating the music: thus it had to be thorough, and it make perfect sense to write, song-by-song, in the order he produced them. Mine is structured by my listening to the album. No, it’s not in track-by-track order, but it is structured by what I heard then (and how those things seem now, looking back), not by what Bowie did when. I think that’s part of what occasionally makes us hear different things? But I’m not sure about that.

Thanks again to Glenn Hendler. A somewhat lengthier version of this conversation is on the Patreon, for those interested, along with other stuff.

Posted by col1234

Posted by col1234