DISCOGRAPHY (+) SOURCES (-) PLAYLIST (+)

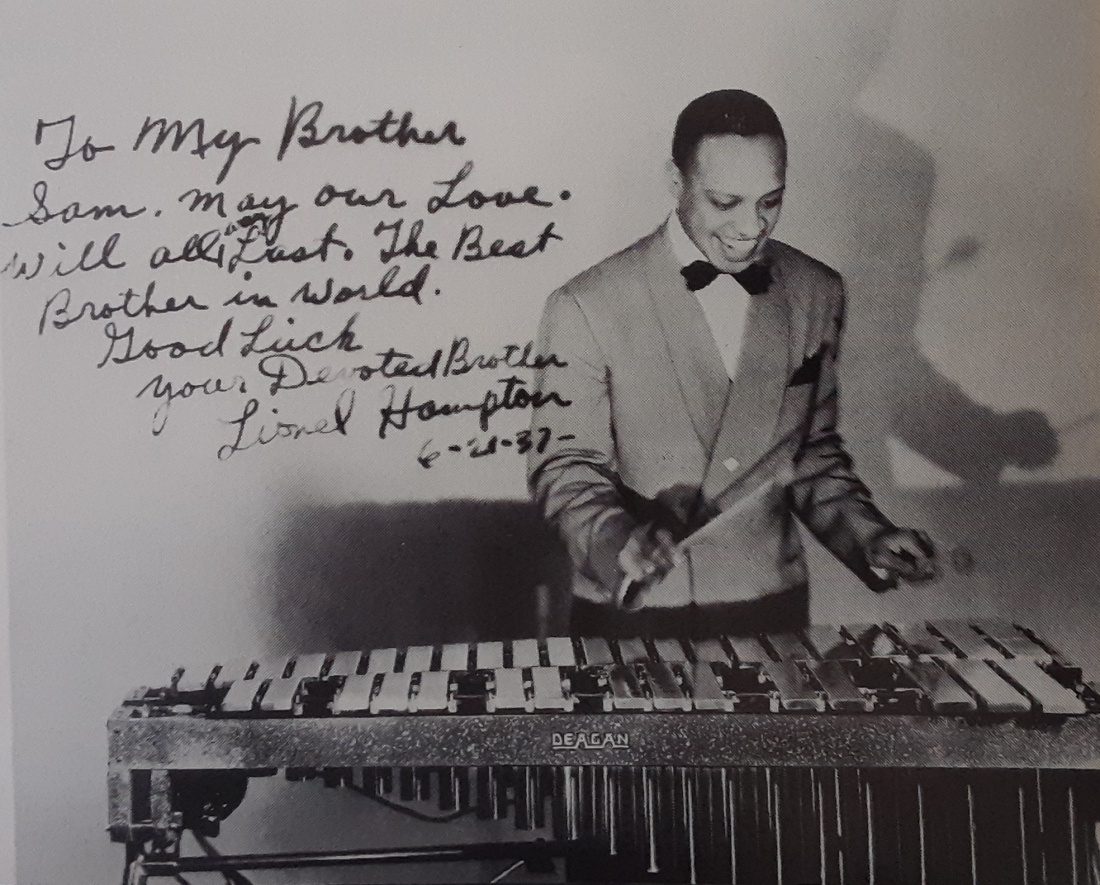

Stomping at the Paramount, New York, 1937

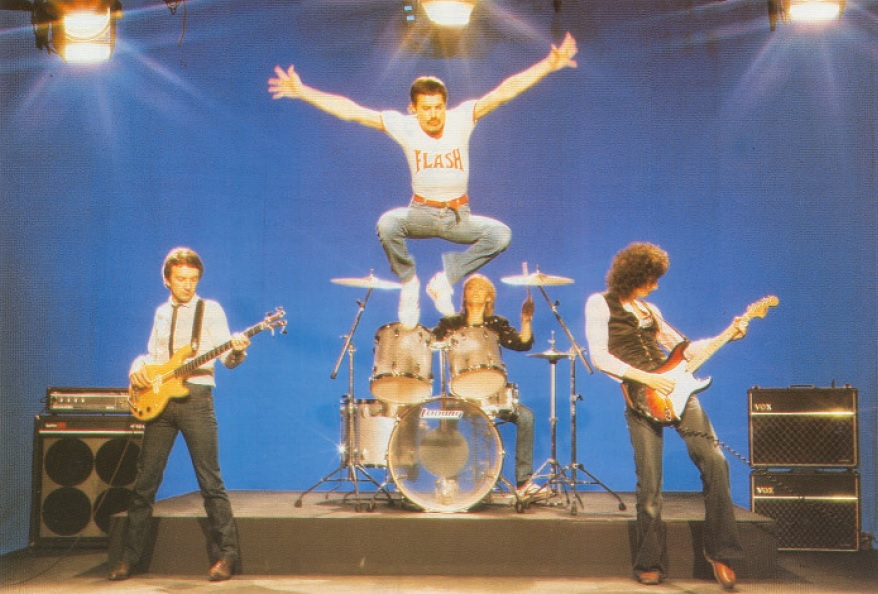

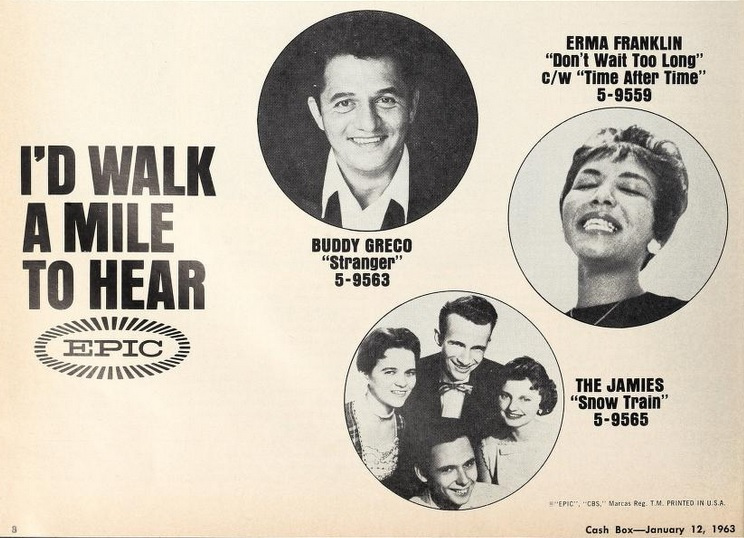

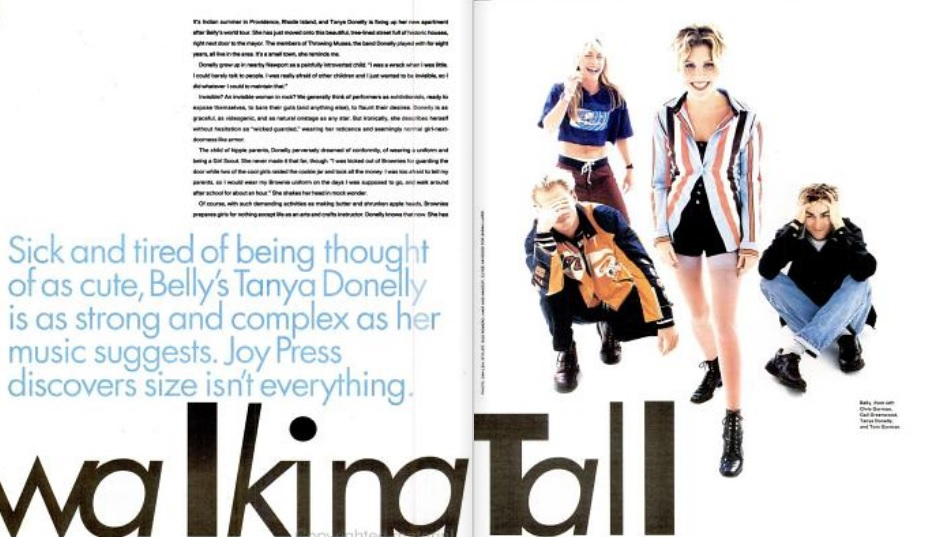

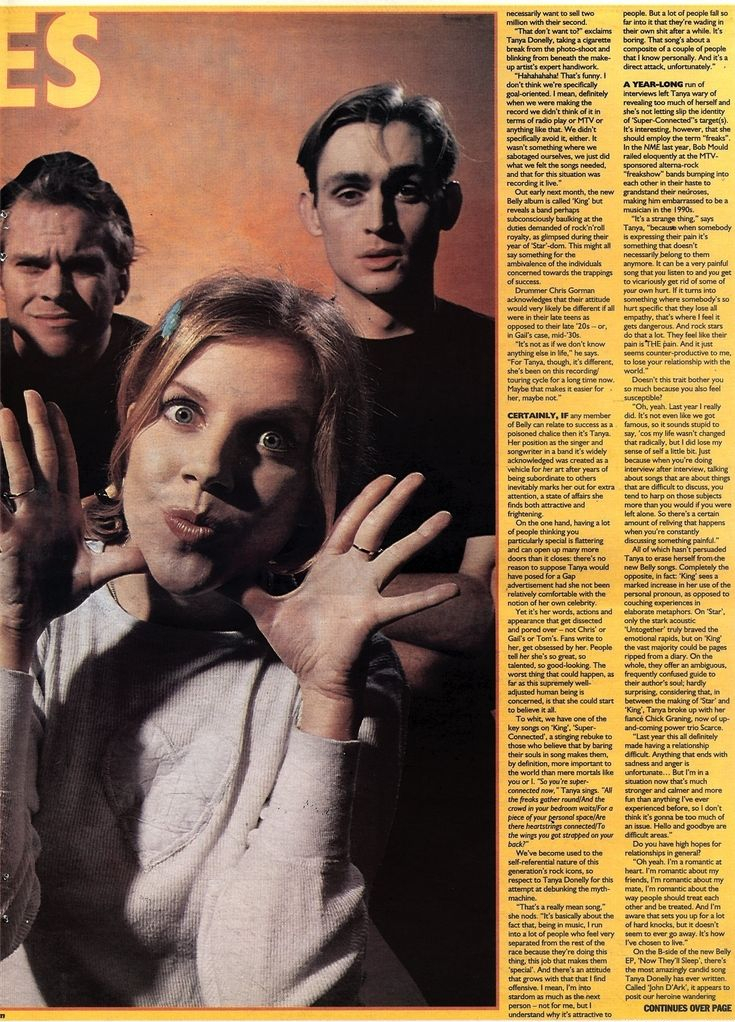

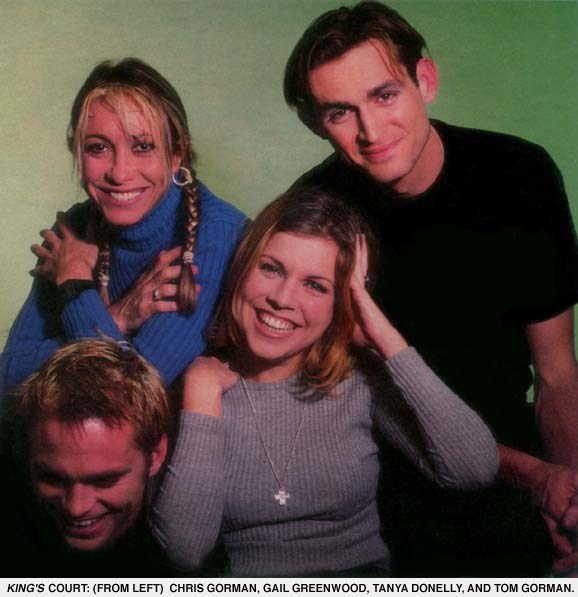

In the 19 February 1938 Billboard, an industry news column notes a regional curiosity: the Memphis Board of Censors is “scissoring” a scene from a just-released Busby Berkeley musical, Hollywood Hotel. It stars Dick Powell and Lola Lane; Ronald Reagan has a bit part. The scene not fit for Memphis cinemas is a performance of “I’ve Got a Heart Full of Music” by the Benny Goodman Quartet.

Berkeley mostly keeps the camera on who’s soloing. Which means for the first minute, the viewer sees Lionel Hampton, playing exuberant vibraphone, and Teddy Wilson, doing magnificent runs on piano. There’s no visual hierarchy. The quartet are dressed identically, in what look like valet uniforms. Vibraphone, piano, and drums are on the same level of the stage, forming a loose triangle. They are a unit, a happy gang.

After Goodman solos, the quartet kicks up the tempo, with Gene Krupa and Hampton battling to do the swiftest percussive run—Krupa on his snare; Hampton on the upper part of his vibraphone, ending each phrase with a flourish as if dotting the “i” in his signature. Goodman laces through their barrages. Wilson puts floorboards under it.

The Card Shuffle

Having an integrated group in 1937 or 1938, particularly when you’re touring the South, takes sleight of hand.

Benny Goodman opens with his all-white band. Kids get up and dance. There’s an intermission and Teddy Wilson comes on. But he’s not officially part of the band, so you can say he’s been hired to fill time while the Goodman Orchestra takes five. Goodman and Gene Krupa play with Wilson. Well, that’s a novelty, all right, this “trio” bit but again, it’s only the sideshow. Then Lionel Hampton joins in on vibes, and you have a racially integrated quartet playing to white teenagers in Dallas.

The strictures of Jim Crow were so fundamentally absurd, so much a vicious child’s capricious set of rules, that one could try to introduce a new rule, like throwing an unexpected queen of hearts onto the pile. So yes, there cannot be integrated musicians in a jazz band that’s playing for a white audience. Yet within the intermissions, this band, this audience, does not exist. Something else does, thus something else can appear in the space left open, in the empty hall called “special attractions.” After all, the audience doesn’t pay for intermissions. This is a free time, in various senses.

Wilson, many years later:

Contrary to popular belief, Benny Goodman was not the first to introduce small groups to jazz…it was original because it was interracial and played publicly as such…I think the instant success of the recordings was due to the refreshing quality they had.

The Kid

Benny Goodman, ca. age 10 (ca. 1919) [Ken Whitten Collection]

Benny Goodman was born in 1909, in Chicago, to Jewish immigrants. His father, David, came from Warsaw; his mother, Dora, from Kovno, Lithuania. They lived in the Maxwell Street neighborhood. David worked in stockyards and as a tailor; Dora gave birth to twelve children and raised them. The Goodmans shifted from tenement to tenement, once spending a winter in an unheated basement room. “A couple of times there wasn’t anything to eat,” Goodman wrote in his memoir. “I don’t mean there wasn’t much to eat. I mean anything.” The Goodmans drank coffee once they were weaned “because milk for so many kids cost more than Pop could afford.”

Poverty was in his bones. Memories of waking up cold, wondering if there’s any left of that half-loaf of bread, of having to keep one step ahead of a landlord. By his twenties, Goodman was well-off and he died rich, but he acted as if it all could go south tomorrow, and then you’re back in the basement, drinking cold coffee.

In games of cops and robbers, the cops always got the worst of it…because in that kind of neighborhood, the cops represented something that never did much for the poor people…I grew up with pretty much a resentment against the way folks like my father and mother had to work…making a go of things with most of the breaks against them.

Goodman, on growing up in Chicago

“If it hadn’t been for the clarinet, I might just have been a gangster,” Benny once said. This was bluster, as his father wouldn’t have had it. David Goodman devoted his life to boosting his children up a rung of the ladder; he’d bought into the promise of America in the way only someone working fourteen hours a day in a stockyard could (just as Benny began to have success, David was run over on a Chicago street, dying soon afterward). He urged his kids to do well in school, to find jobs that weren’t in a sweatshop. Benny’s sister Ida became a stenographer. For the Goodman brothers, music looked feasible. They could play weddings and bar mitzvahs, instruments were affordable on the installment plan, and there were free lessons at synagogues and at Hull House on Halsted Street, which had an amateur band.

Benny, smallest of the Goodmans sent off to be musicians, got the smallest instrument at the synagogue, the clarinet (his bigger brothers got tuba and trumpet). He was a natural, quickly able to play intricate runs of notes at brisk tempos, enlivening his lines with rasps and growls. A music teacher named Franz Schoepp gave Benny “the foundation”—the correct embouchure and fingering, breath control—and stressed the need for daily scales, a regimen that Goodman kept for the rest of his life. He died while rehearsing.

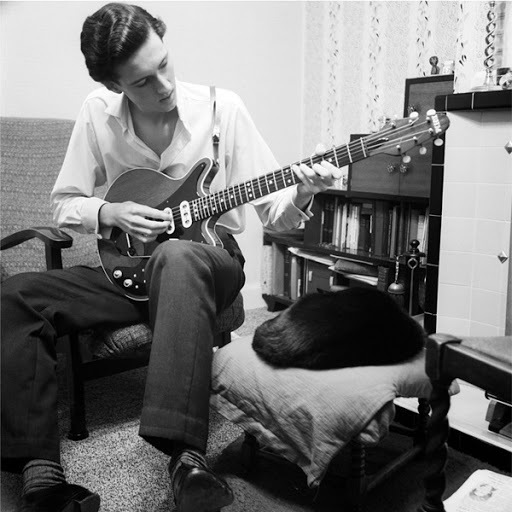

He was of the first generation who heard jazz on disc: fourteen when King Oliver and Louis Armstrong started cutting records, seventeen when Jelly Roll Morton began releasing his Red Hot Peppers sides. He was like Paul McCartney and John Lennon thirty years later: teenagers obsessed with records, looking for a way into the new music, trying to make it theirs. Goodman sat in music stores, listening to sides for hours. If a trumpet or piano solo caught his ear, he’d play it until he’d memorized the notes. “I always liked to play free, from the very start,” Goodman wrote. “And when we got hold of a new chord or a good lick, that was a thrill like nothing else.”

How to describe his clarinet style? “Unfeigned and lusty,” Gary Giddins wrote. “Goodman’s rhythmic gait was unmistakable; his best solos combined cool legato, a fierce doubling up of notes, and the canny use of propulsive riffs.” Allen Lowe called Goodman “a brilliant technician who…polished his earliest enthusiasms into a method that was at once both urbane and earthy.” By his late teens, Goodman could play anything on clarinet, in any register, near-flawlessly—bandleaders relied on him for a “hot” solo whenever a piece needed a kick. Downplaying the jazz clarinet’s hooting circus-barker qualities, he worked on smoothing his tone, on having a grace in his phrasings.

Goodman’s quickly-maturing style is heard in his first major solo on record, Ben Pollack’s “Waitin’ For Katie” (1927). Goodman, eighteen years old, gets a full chorus (thirty-two bars) at the start of the piece. Mainly keeping to his clarinet’s middle register, in full control of his volume, with a bright tone, he soon moves away from the theme. It’s as if after having made introductions, he glides, happily distracted, into a livelier room.

Ben Pollack’s Park Central Orchestra, 1929 (BG fifth from right) [BG Archives, Yale]

Having dropped out of school at fourteen, Goodman worked at Colt’s Electric Park outside Chicago, and played cabarets and dance halls. “I was pretty restless and never stayed on a job very long if a new one came along where I might get a little more money and sit in with better players,” he said. A break came in 1925 with Ben Pollack’s jazz band, based in Los Angeles. Goodman took a train from Chicago, “a skinny kid in short pants, with a clarinet under my arm.”

By 1929, when Goodman hit New York with Pollack’s group, he’d become a showboat, hogging solo choruses, leaning back so far in his chair while he played that he was nearly horizontal. Meanwhile Pollack, with designs on becoming the next Rudy Vallee, got cheesy—he made band members wear tiger masks when they played “Tiger Rag” or undertaker suits for “St. James Infirmary.” The break was inevitable. When Pollack complained about Goodman wearing dirty shoes on stage (he’d been playing handball earlier), Goodman quit. If it hadn’t been for that reason, there would have been another one.

Goodman as jazz pro, ca. 1929

To understand the situation in music around 1929, it is necessary to appreciate the fact that the public at large didn’t have much contact with the men who actually played the music…nobody put the names of the musicians on the labels of records. The leader was the top man, and that’s all there was to it.

Goodman

Goodman joined one of the few lucrative musician sets of the early Depression—a New York-based group of freelance players who cut records, played Broadway musicals, did radio performances, filled in if a dance band needed an extra for a night. They were the elite of the white jazz scene (members included Artie Shaw and the Dorsey brothers), having to sight-read anything put in front of them and nail it in a take. In 1930 alone, Goodman played in roughly three dozen sessions.

Some of his sideman performances were astonishing. See his solos on Ted Lewis and Fats Waller’s “Crazy ‘Bout My Baby” and “Royal Garden Blues,” where, as his biographer James Lincoln Collier described it, Goodman sounds like he’s walking on stilts, playing “truncated eighth notes.” He was part of an all-star gang for Hoagy Carmichael’s “Rockin’ Chair” and “Barnacle Bill the Sailor” (with Bix Beiderbecke, Bubber Miley, Tommy Dorsey et al—-Goodman cooks in his solo on the latter, on which you can hear Joe Venuti sing “Barnacle Bill the shithead”); he played in the last-ever session of Bessie Smith, and the first-ever of Billie Holiday, within days of each other in 1933. His bass clarinet on Red Norvo’s “In a Mist” and “Dance of the Octopus” previewed his and Lionel Hampton’s exchanges in the Quartet.

But Goodman got on his bandleaders’ nerves and it was costing him jobs. A child prodigy now in his twenties, he chafed under orders and held lesser musicians in contempt, once mocking another woodwind player while on stage. His facility made him arrogant. “Conductors would tell me how to handle something…That rubbed me the wrong way,” Goodman wrote in his memoir. “I hadn’t grown up in the habit of following somebody else’s idea of what the music meant. I figured I had a way of playing the instrument that was my own, and I wanted to stick to that way. Then, too, some of these conductors just didn’t know their stuff.” Tenor saxophonist Bud Freeman, who played with Goodman for a time, said that “Benny was not cruel, he just lived in a kind of egomaniacal shell…he thinks of himself as being apart from the world. Benny’s world is built around Benny.”

Hired to form a dance band for Russ Columbo in 1932, Goodman irked the musicians by being miserly on salary (“I drove a pretty hard bargain with some of the boys, which they resented.”) One resentful player was the drummer, Gene Krupa, who never wanted to work with Goodman again.

Basher

Gene was as magnetic as a movie star.

Anita O’Day

I was grunting and sweating as if I was in a steel mill.

Gene Krupa, on playing drums

Gene Krupa was born in 1909, ninth child in a Polish-American family who lived on Chicago’s South Side. “My father died pretty early,” Krupa recalled. “Mama was a milliner, she had her own store. And she was determined to bring the kids up right.” By age ten, Krupa was doing minor jobs at a music store, where he memorized the titles and label numbers of the records in stock. He bought a “rag-tag Japanese set of drums for $16,” he told Burt Korall. “Drums were the cheapest item in the wholesale catalog.”

His mother wanted him to be a priest (large Catholic families often sent one of the boys to seminary; a form of tithing), so Krupa went to St. Joseph’s College, a seminary prep school in Rensselaer, Indiana. “I gave it a good try,” he said of the priesthood. Instead, his time at St. Joseph’s made a musician out of him, thanks to its magnificently-named music professor, Father Ildefonse Rapp.

Krupa left St. Joseph’s at sixteen to drum in Chicago dance bands: the Hoosier Bellhops, Ed Mulaney’s Red Jackets. He played in a gangster-run “black and tan” club in Indiana. Offstage, he was in the Austin High gang, a Chicago-based group of young white hipster jazz musicians who scoffed at their contemporaries, calling them hacks and sell-outs, and greatly favored Black jazz players.

He studied the great Black drummers of the era, including Chick Webb (“I learned practically everything from him”), Zutty Singleton, and Johnny Wells; he’d work out their rhythms on desks and chairs until his hands were swollen. Seeing the New Orleans drummer Baby Dodds at Kelly’s Stable “killed me,” Krupa said. Dodds used the full range of the drum kit, from the rims to the cymbal bells, and showed how to “develop ideas and build excitement through a tune,” Krupa said. “Right before going to the cymbal for the rideout, Baby would move into this press roll, dragging the sticks across the snare.”

Dodds was also a cocky, eye-catching presence behind the kit, chewing gum while he played, grimacing and beaming while he worked his snare and toms. Krupa saw that a drummer didn’t have to be anonymous. “I’m a child of vaudeville,” he told Korall. “The first thing you have to do is get their attention.”

Krupa (third from left), ca. 1927

Krupa’s first recording session was in 1927, for McKenzie and Condon’s Chicagoans (an Austin High group). He brought his full kit into the studio. Drummers cutting tracks in the acoustic era would often just play snare, cymbal or woodblock—nothing else could be heard on the record, so what was the point? Krupa wanted greater dimension and dynamics in the studio, especially once electrical recording, and superior mikes, became standard. His set-up—snare, kick, mounted tom, larger floor tom, foot-wide hi-hats, and four large crash or splash cymbals (plus a gong, once he became a bandleader)—was a blueprint for the next generation of jazz drummers. He was also among the first to put his initials on the kick drum’s shield. “I made the drummer a high-priced guy,” Krupa later said.

He soon had a cult. Mel Tormé , as a kid in Chicago, would walk by the Krupa family’s grocery store “just to see the name on the green awning.” Alto saxophonist Hymie Schertzer, who played with Krupa in the Thirties, saw Krupa “really start to become a crowd puller. His solos had great visual appeal. The crowd saw someone knocking his brains out and they loved it.”

Goodman needed this. In 1934, he founded his own jazz orchestra, as he finally accepted that he couldn’t work for anyone. Everything was in place: a group of ambitious players; a charismatic young singer, Helen Ward; a set of hot arrangements bought from Fletcher Henderson. But his drummer was Stan King, whom Ward described as “a strictly society-type of musician. Everything he played was boom-cha, boom-cha. There was no fire.”

So Goodman brought in Krupa, who had sex appeal, vigor, a sense of fun. Krupa was wary at first, given his history with Goodman, but the pay was good, the audiences better. The Goodman Orchestra, in a year’s time, went from being one of three bands vying for ears on the radio show Let’s Dance to the hottest jazz group in the United States.

Goodman, orchestra, Helen Ward: Chicago, 1935

Not long before the West Coast tour that would make his name, Goodman, in early June 1935, went to a party at Red Norvo and Mildred Bailey’s place in Forest Hills, Queens. Bailey’s cousin, a drummer, was there, as was the producer John Hammond, Goodman’s friend, benefactor, and future brother-in-law. So was Teddy Wilson, a pianist whom Hammond was using as a bandleader and arranger on Billie Holiday’s records, and with whom Goodman had worked a few times before. Wilson jammed with Goodman and Bailey’s cousin deep into the summer night. The party arrangement—clarinet, piano, drums (that is, playing brushes on a suitcase)—had a real snap to it, everyone thought.

“What I got out of playing with Teddy,” Goodman wrote later, “was something, in a jazz way, like what I got from playing with [a] string quartet…It was something different from playing with the band, no matter how well it might be swinging.”

The Artisan

In February 1972, the critic Whitney Balliett saw Teddy Wilson playing at the Cookery, a Greenwich Village restaurant. Wilson turned sixty that year. At the Cookery, he played standards in which he’d staked claims over the decades—“Tea for Two,” “Sweet Lorraine,” “Love for Sale.” Balliett wrote that Wilson’s “famous style was in place—the feathery arpeggios, the easy, floating left hand…the intense clusters of notes that belie the cool mask he wears when he plays….[He] is a marvel, and we must not take him for granted.”

It was easy to take Teddy Wilson for granted. “A segment of the jazz press has always accused Wilson of too much gentility,” John Lissner wrote in 1974. There’s little of the legendary about him. Given how many “legendary” artists were monstrous off stage, this is a blessing, one of many that Wilson offered in his life.

Wilson was born in Austin, Texas, in 1912. His parents taught at Sam Houston College, then at Tuskegee University in Alabama. Growing up in the Tuskegee music scene, a cultural oasis for African Americans in the South, Wilson learned piano and fell into jazz upon hearing Tuskegee students’ records: Fats Waller, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong. As with Goodman, listening to 78s was Wilson’s conservatory. He’d slow speeds to a crawl and lift the needle back yet again to the outer groove until he knew a solo note-for-note. In 1927, on vacation in Detroit, he saw a jazz band at last and told his mother he wanted to be a professional jazz musician. She said to try college for a year and see how he felt then. If he still wanted to be a musician, “be a good one.”

By 1929, he was playing in Midwestern jazz bands: Speed Webb’s, and later, Milt Senior’s. For a time he was at a club owned by Al Capone. It was like working at a bank, Wilson said, as you never worried about getting paid.

His finishing school was hearing and meeting Art Tatum, Fats Waller, and Earl “Fatha” Hines. Wilson’s bass figures elaborate on Waller’s stride basslines, with Wilson breaking up Hines’ patterns by alternating notes or playing thick tenth chords (“I can stretch the tenth in the left hand”) to create “almost fugal figures in the bass,” as Collier wrote. Drawing from Tatum and Hines, Wilson developed his technique of using right-hand octaves to span wide-leaping melodies along the piano’s higher keys. It was as if Wilson had created three-handed piano, the critic Gunther Schuller wrote—a tenor line and a bass pattern played near-simultaneously by his left hand that sustain the melodic adventures of his right.

There’s a coruscating intelligence in Wilson’s piano playing—his love of developing melodies and rhythms, his eternal lightness, his crispness of articulation on the keyboard. He’d stint on dynamics and showy effects so as to have an elegant flow of notes in bright continuity (particularly in the Goodman Quartet, where he was the de facto bassist). “He doesn’t mind easing up—on himself, on his listeners, on his fellow players,” as Schuller wrote of Wilson. It was as if he was centered on the ground yet also high above it, absorbing and refracting light. Goodman, in his autobiography:

Teddy gets terrific swing out of his left hand, playing a steady figure on the beat while he gets off these patterns in the right hand, especially in a medium tempo—and that’s what really sent me…He had a fine harmonic sense so that he can get all kinds of color into his background harmonies without screwing things up with a lot of fancy chords…Teddy is nuts about accuracy, as I am. He’ll never let a bad note get away from him if he can possibly help it, which means he’s always thinking a little bit ahead of what’s he’s actually playing.

Wilson and Goodman would work together for half a century. For Goodman, who went through musicians like subway tokens, Wilson was always the pianist, no matter how much they weren’t getting along. Which, as the years went on, was often. Sublime collaborators, they were never friends. Helen Oakley, who knew them both, said “Benny was probably mystified by Teddy’s rather chilly reserve, especially since they played so well together…They never really hit it off temperamentally. I assume Teddy must have sized Benny up and found him lacking in many ways.”

Wilson’s perceived “chilliness” was the well-oiled defense mechanism of a brilliant musician, the child of intellectuals, who was regarded by much of his country as a second-class citizen. “He rose above everything with the same deadpan expression and ramrod-straight posture with which he sat at the piano,” Oakley said.

Talking to Nat Hentoff in 1974, Wilson said he’d been heartened by responses he got from his students, who, in some cases, were hearing jazz for the first time. He spoke like a man who knew his worth:

I do believe that any youngster who is genuinely interested in music eventually has to leave much of rock behind. I don’t want to sound immodest, but what musicians like myself play is like Ph.D. music compared to the nursery‐school sounds of a lot of rock and roll. They’ve got to grow out of it. And that goes for their parents, too. I mean the kind of parents who try to pretend they love rock so that their kids won’t think they’re old fogies.

One, Two, Three

After the jam in Queens, Goodman and Hammond, within days, got a trio recording date booked in New York.

A jazz trio wasn’t novel. New Orleans jazz groups had arranged pieces for three or four players; Johnny Dodds had cut trio sides in the Twenties. Even Goodman did one in 1927: “Clarinetitis.” The latter is Goodman’s show. He solos throughout, half in his high register, half in his lower. The piano and drums, if lively, are there to back him up—he’s their employer.

The Benny Goodman Trio would be something else: a series of conversations between Goodman and Wilson as moderated by Gene Krupa, who gave some of his most subtle performances, inspired by Wilson’s light touch on the keyboard. “Gene worked into the idea fine, as we knew he would,” Goodman later said.

The lack of a bassist (instead, Krupa tuned his bass drum to Wilson’s low F on the piano) left space for everyone to fill. “The bass was absent and you got a good chance to hear the way I was using the left hand on the piano, coordinating it with Krupa’s bass drum,” Wilson said. “There was no sound like it in records then.”

Saturday, 13 July 1935. Goodman, Wilson, and Krupa set up in Victor Records’ studio on East 24th Street. Goodman has chosen four songs: well-worn compositions, most from the Twenties. After You’ve Gone, Body and Soul, Who?, Someday Sweetheart. Titles that a record buyer would recognize, if not the name on the label. Everyone in the room knows these songs; they’re as comfortable in them as in an old pair of shoes.

They start with “After You’ve Gone,” doing two takes. In the second (the released take), Goodman plays the melody straight, with Wilson responding in a romping flow of, at times, single-note patterns. As Loren Schoenberg noted, under Goodman’s solo, Wilson does a tritone substitution (a favorite bebop tactic) that adds a knot of tension, one quickly untied. It closes with a Krupa drum break and Wilson and Goodman trading twos. “After You’ve Gone” is a heartbreak song, but here it soars like a lark.

On to “Body and Soul,” one of jazz’s deepest reservoirs. It’s Wilson’s show. He fills his bass figures with triplets and runs of 16th notes; they’re like the changing moods across a cloud’s face. “Who?” goes further out—Wilson plays the lead melody; Goodman becomes a New Orleans jazzman for two choruses; Krupa’s solo break is met by monosyllabic responses, as if he’s playing in court to a pair of stone-faced justices; Wilson, in his solo, alters the meter so that he’s two beats off throughout, with Krupa deftly responding. “Someday Sweetheart” is like being in a conversation at a party where, by some miracle, everyone is witty.

Goodman, Wilson, and Krupa took the jazz past and folded it into the future. The Trio’s singles sold, too: “Body and Soul” would be Victor’s top-selling disc in LA by late 1935.

Goodman’s Orchestra, having conquered Los Angeles during a residency at the Palomar Ballroom in 1935, became nationally-known, the face of the “swing” craze. On Easter Sunday 1936, at a Chicago concert that Helen Oakley organized, Wilson played on stage with Goodman and Krupa for the first time. “Benny was extremely dubious,” Oakley said. “He was afraid that if he and Teddy played together in public, it might not be found acceptable. ‘The hotel will never allow it,’ he told me.”

Goodman later said it was no grand thing. “When Teddy came on to play with Gene and me, it didn’t make much difference to us,” he wrote in his autobiography. Although the Trio hadn’t played together in nearly a year, it was as if they’d recorded the Victor sides the day before. “The three of us worked in together as if we had been born to play that way and one idea just came after another.” (They soon cut more Trio sides, including Wilson’s master class “China Boy,” the modulation-crazy “Oh Lady Be Good,” the piping hot “Nobody’s Sweetheart.”)

The crowd loved the Trio—it was an ideal debut audience, a mingle of urban hipsters and high society types in a select “jazz club.” When Goodman returned to LA in triumph in summer 1936, with Wilson now part of his act, John Hammond urged him to keep pushing forward. Wilson had established a beachhead; time for another advance. Hammond was a regular at a club called the Paradise and liked its bandleader, who sang and played vibraphone, drums, and piano. One night, Hammond brought Goodman, Wilson, and Krupa to see him.

“Benny sat at one of the front tables and I remember thinking he looked familiar,” Lionel Hampton wrote decades later. “With his granny glasses and his business suit, I thought maybe he was a politician.”

Hamp!

When Lionel Hampton was thirty-one, he met his dead father.

Charles Edward Hampton, while his son was still a child, left Kentucky to fight in France in World War One. As far as everyone knew, he’d died there. His mother “wrote all kinds of letters trying to find out what happened,” to no response, Lionel wrote (Charles was assigned to a French unit, as Woodrow Wilson’s army was segregated). Then one day in 1939, Lionel was playing with the Goodman Orchestra in Dayton. Backstage he met a local boy who asked him if he visited his father whenever he was in town. “I don’t have a father,” he told the boy. “My father died in the war.”

But Charles Hampton, blinded by mustard gas, had instead spent two decades in a Veteran’s Administration hospital in Dayton. Lionel went to see him there. Charles asked him about his mother, said he hoped she was doing well, said he’d heard that his son had become a famous musician. Charles passed away, this time for good, not too long after that. “Today I am as old as he was when he died,” Lionel wrote, in his 1989 memoir. “When I look in the mirror I see my father.”

Lionel Hampton’s was a life of coincidences, stage shows, and wild reversals of fortunes: he was a grand character in a world packed with them. The Hamptons and Morgans (his mother’s family) were inveterate performers. His bootlegger uncle Richard, friend to Al Capone and Bessie Smith (and who was driving in the crash that caused the latter’s death). His grandmother and mother, who were both storefront preachers. His no-nonsense wife Gladys Riddle, who managed his money and career until she died in 1971. “Nothing has been the same since,” he wrote twenty years later.

Lionel Hampton, ca. age 6 (marked with arrow) and extended family, ca. 1914

Born in 1908, Hampton grew up in Birmingham, Alabama. His grandfather was a locomotive fireman, his grandmother was in God’s employ. Sunday meant a full day in church, where at least there was music. “That red-brick building rocked on a Sunday!” Hampton wrote. “My favorite instrument was the big bass drum. The sister who played it was pretty big, too. She’d beat that drum for hours and then all of a sudden the spirit would grab her…Seemed to me that drumming was the best way to get close to God.” One Sunday, Hampton picked up a mallet and started pounding the bass drum. From then on, he was a drummer.

In the late 1910s, the Hamptons moved up to Chicago, where Uncle Richard was getting rich in the liquor business. Lionel, barely a teenager, walked around town wearing silk shirts, was forever drumming on tables and floors, and spent much of his time in the basement stirring sour mash for his uncle’s whiskey. His mother thought he needed salvation of some kind and sent him to the Holy Rosary Academy in Kenosha, Wisconsin, where he was taught by Dominican nuns.

And like Gene Krupa, Hampton got his core drumming lessons at Catholic school. Sister Pedra taught him “the flammercue and ‘Mama-Daddy’ and all that stuff on the drums” and she’d kick him in the rear if he was holding the sticks improperly (“she wore pointy-toed shoes, too”).

Back in Chicago, Hampton took up xylophone (a gift from Uncle Richard). He’d translate trumpet and saxophone solos from Louis Armstrong and Coleman Hawkins records into xylophone lines. He got another, informal musical education at his uncle’s parties, where the likes of Bessie Smith and Bix Beiderbecke would hang out together. “It’s kind of sad to think about all those black and white musicians going around admiring each other, playing off each other, jamming privately together and yet knowing they couldn’t be seen together in public,” Hampton wrote.

He joined Les Hite’s band as a drummer. “I was already playing with a heavy afterbeat, getting that rock ‘n’ roll beat…I wanted people to dance, to have a good time, clap their hands, and they would do it to my drumming.” Shifting operations to California, Hampton was known as a shameless showman. He’d throw his sticks in the air, run across the stage, scream as if being mauled by a tiger during “Tiger Rag.” Louis Armstrong was impressed enough to nickname Hampton “Gates” (“cause you swing so good”) and brought Hampton into a 1930 recording session.

Hampton plays Oak Knoll Naval Hospital, sometime during the war (US Navy archives)

Hampton plays Oak Knoll Naval Hospital, sometime during the war (US Navy archives)

Here, at Okeh’s LA studio, Hampton first saw a vibraphone: the more distinguished, eccentric cousin of the xylophone (where the xylophone has wooden bars, the vibraphone’s are metal, thus able to sustain notes longer; the latter’s tone is also altered by electric-powered fans that rotate at the upper ends of resonator tubes.) Less than a decade old, the vibraphone was still considered a novelty, used for sound effects on records and radio broadcasts. “At that time they were only playing a few notes on it—bing, bong, bang—like the tones you hear for N-B-C,” Hampton wrote. “All that big beautiful instrument and nobody could do a thing with it.”

Hampton saw that its keyboard was the same as a xylophone’s, so he played one of Armstrong’s trumpet solos on it, note for note. Armstrong, delighted, put Hampton on vibraphone for “Memories of You,” which would be the first jazz recording (or so Hampton claimed) with vibes on it.

A three-octave M75 Century vibraphone that Hampton donated to the Smithsonian.

Hampton, billed as “The World’s Fastest Drummer,” now shifted to vibraphone to vary a set. Gladys Riddle, his partner and manager, was convinced that playing vibes would be how he made his name. There were plenty of contenders for World’s Fastest Drummer out there, few master vibraphonists. After hours at nightclubs, he’d sit at a piano and play two-finger patterns on the treble end, working out solos destined for vibraphone.

By 1933, he was at the Red Car Club in LA (“a big beer garden…the chicks who worked there wore blue-jean overalls”) which, aiming for a choicer clientele, changed its name to the Paradise. It was here in summer 1936 that John Hammond brought the Benny Goodman Trio to see Hampton play. Soon enough, “I turn and there is Benny Goodman, playing right next to me,” Hampton said. “The four of us got on the bandstand together and man, we started wailing out. We played for two hours straight.”

Goodman invited him to a recording session the following day, out in Hollywood. Rousted from bed by Gladys, Hampton dashed to the Paradise to get his vibes and then booked it to RCA Victor’s studio.

Melancholy Dinah By Moonlight: 1936

As with the first Benny Goodman Trio date, the earliest Benny Goodman Quartet recordings are a redaction of a more free-flowing encounter. Tight responses to hours-long jam sessions, both have to conform to the strictures of making records in the mid-Thirties. Three minutes a side; two or four sides cut in a few hours.

“Moonglow,” the first Quartet recording (21 August 1936), was cut at the end of a session primarily devoted to Goodman’s big band. Goodman and Wilson had recorded “Moonglow” two years earlier, a Will Hudson song that pillaged Duke Ellington (“Solitude” and “Lazy Rhapsody” lie within it). After a piano intro, a 16-bar “head” chorus, in which Hampton safecracks the sound of Trio, playing lapping waves of vibraphone notes under Goodman’s lead melody. As often on Quartet tracks, wherever Wilson goes, Hampton makes way—he voices his vibraphone chords so as to not to clash with Wilson’s piano, in a delicately precise harmony (and they’ve played together but once before this!). After a Wilson solo and a reprise of the head chorus, Hampton takes his debut: two full choruses, soft-shoe dances of mostly 16th notes, with stop-time sections. It’s what I imagine the inside of a snow globe sounds like.

Five days later, they cut “Dinah.” There will be far more Quartet recordings to come, and many brilliant ones, but this is the quintessence, already—everything’s here.

Hampton opens by playing so fast that it’s a blind guess as to where the downbeat is. Goodman unwraps the melody like a Christmas present; Wilson spends much of the time in accompanist mode, straight man in a comedy revue; Hampton and Krupa sound each other out, having a blast—Krupa underwrites Hampton’s first solo chorus with polyrhythms on his toms and gives “a disorienting snare drum accent just before the kick stroke” (Giddins) in the third chorus, as Hampton plays a crafty cross-rhythm on vibes. Goodman roams through the theme melody, finding new corners within it, with Wilson giving a four-bar interjection. It ends with everyone talking at once, a polyphonic close-out.

This session, which also produced “Exactly Like You” and “Vibraphone Blues” (with Hampton on vocal), convinced Goodman that Hampton had to be part of his band. He offered Hampton a $550 one-year contract (inflation-adjusted, about $10,000) and to pay for train tickets to New York. As Hampton recalled, Gladys said they should take a car instead so that if things went south, they could just get back in and go home. They packed up her white Chevrolet with Hampton’s drums and vibraphone and drove cross-country. Along the way, they got married.

The Hamptons moved into an apartment in Sugar Hill; Lionel went to the doctor (Goodman’s request—he wanted all his musicians insured) and cut more Quartet sessions. “Sweet Sue” is another intricate dialogue of Wilson and Hampton; “My Melancholy Baby” is a collection of masterful statements, from Goodman to Wilson to Hampton; “Stompin’ at the Savoy” finds Wilson, Goodman, and Krupa marching in formation against a Hampton solo; “Whispering” is Goodman soloing in an exquisite tone while Wilson, then Krupa, play obbligatos in response—Hampton swings in, spins around the room, slip-slides out.

Otis Ferguson, writing for the New Republic, saw the Quartet play during a Goodman set at the Pennsylvania Hotel in New York, at the tail end of 1936.

They play every night — clarinet, piano, vibraphone, drums — and they make music you would not believe. No arrangements, not a false note, one finishing his solo and dropping into background support, then the other, all adding inspiration until, with some number like “Stomping at the Savoy,” they get going too strong to quit—four choruses, someone starts up another, six, eight, and still someone starts—no two notes the same and no one note off the chord, the more they relax in the excitement of it…This is really composition on the spot…it is a collective thing, the most beautiful example of men working together to be seen in public today.

Gene Krupa, a handsome madman over his drums, makes the rhythmic force and impetus of it visual, for his face and whole body are sensitive to each strong beat of the ensemble; and Hampton does somewhat the same for the line of melody, hanging solicitous over the vibraphone plates and exhorting them (Hmmm, Oh, Oh yah, Oh dear, hmmm). But the depth of tone and feeling is mainly invisible, for they might play their number “Exactly Like You” enough to make people cry and there would be nothing of it seen except perhaps in the lines of feeling on Benny Goodman’s face, the affable smile dropped as he follows the Wilson solo flight, eyes half-closed behind his glasses…The quartet is a beautiful thing all through, really a labor of creative love, but it cannot last forever.

He was right—it was over in little more than a year.

Ida in Avalon and Dumas: 1937

It galled [Goodman] that something as petty as race prejudice would mess up the music he wanted to hear and play…He understood that a guy like Teddy couldn’t concentrate on his music when he had to deal with hate.

Hampton.

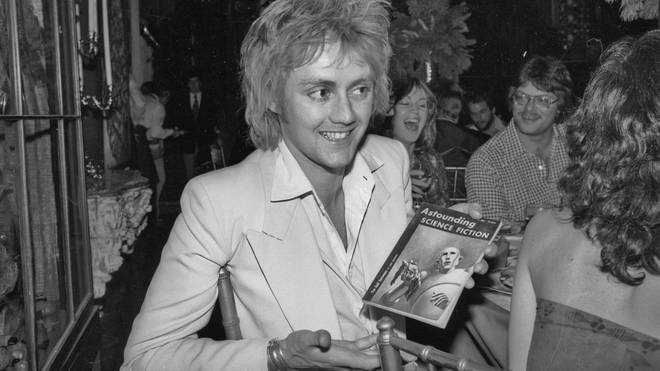

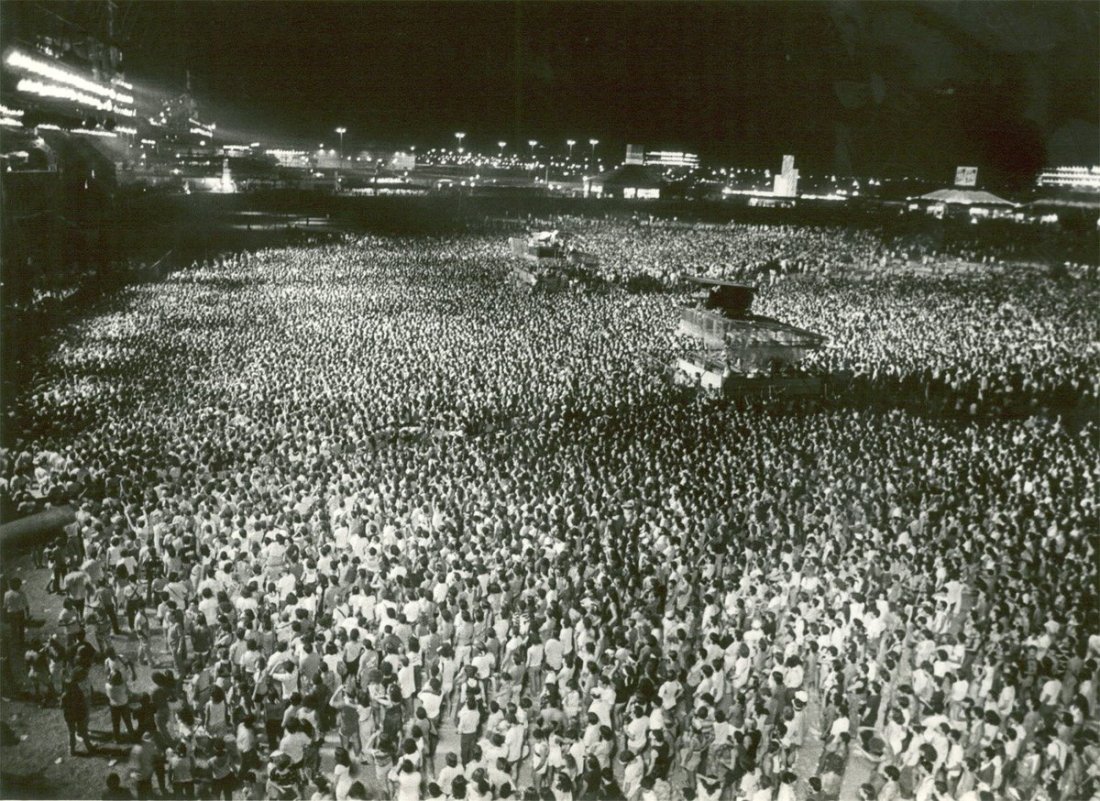

In March 1937, the Goodman Orchestra (and Trio and Quartet) did a two-week engagement at the Paramount Theater in Times Square. It was during Lent, and Goodman had modest expectations. Instead he got a blast of teenage swing fandom—girls in pleat skirts and white buck shoes jitterbugging in the aisles, their cheers so loud that it sounded like New Year’s Eve. Because for the first time in New York, high-school-age kids could see Goodman: the Paramount shows were during the day.

And the audiences were integrated; Black patronage increased sharply at the Paramount during the Goodman stint. John Hammond said he found it “amusing to note that commercial success had a magnificent way of eliminating color segregation.” The residency was hell on the musicians, who did five sets a day at the Paramount, starting mid-morning, while also playing a ballroom gig at night. Goodman only saw the sun when he took a car to the Paramount for his opening show. “When the public wants you, they want you all the time,” is how he described it. “And when they don’t want you, they don’t want you even a little bit.”

People said to me, ‘Why you goin’ South? Those white folks will kill you.’ And I’d say, ‘they’ll have to kill Benny Goodman first.’

Hampton.

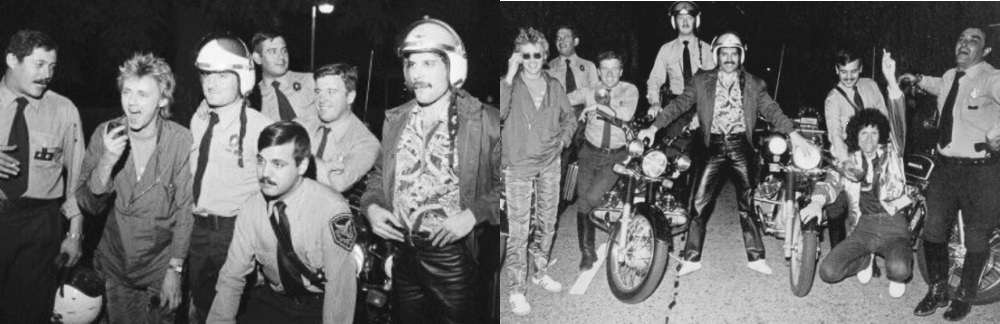

When the Orchestra toured, wending from New York to California in summer 1937, Goodman planned its more southern stops “like a military campaign,” Hampton recalled. He and Wilson endured the usual indignities on the road. “I don’t know how many times Teddy and I were mistaken for servants—Mr. Goodman’s valets.” When Goodman heard stagehands in Richmond calling Hampton a water boy, he dressed them down. “This man is a member of my band,” he told them. “He’s a gentleman and I want you to respect him as such.” (Hampton would sometimes embellish this story by saying that Goodman head-whacked one stagehand with his clarinet.)

In Dallas (a city to which Wilson had gone “with considerable misgivings,” as per Down Beat), Goodman had required by contract that Wilson and Hampton would stay in the same hotel as the rest of the band. Some of the police didn’t like the attention the two got. “Every time one of the kids came up and asked either of them for an autograph, naturally calling them Mr. Wilson or Mr. Hampton, [the cops] would act nasty,” Goodman wrote. When a fan sent a congratulatory bottle over to Hampton, one cop, yelling “no champagne for n—-s!,” knocked the tray to the ground.

One time Hampton and Wilson saw a water fountain marked “Whites Only” and, exchanging a grin, drank from it until a cop screamed at them: “Don’t you ever do that no more!” “Maybe we felt protected by the name of Benny Goodman and just wanted to test the limits,” Hampton wrote decades later.

The Quartet was a band of four bandleaders. They made parallels, their relationships were an intricate traffic pattern. Goodman and Wilson were reserved on stage, Krupa and Hampton exuberant showmen. Hampton liked to map out his solos beforehand; Wilson and Goodman, drawing from their warehouses of memories, could pull melodies out of the air. And while Wilson and Hampton couldn’t get served in a restaurant in half of the country, they’d had more comfortable upbringings than Krupa and Goodman. Wilson, in particular, was more refined than Goodman, who’d pick his nose and plumb his ear in public without a care—it took his marriage to a former aristocrat to class him up a touch.

It was about as ideal a democracy as one could achieve in the United States in the Thirties. Compromise as an aesthetic; a band as a chessboard on which each piece holds the others in place, and within that suspension, infinite daring moves can be plotted.

A New York session on 3 February 1937 produced, in an hour or two, “Ida (Sweet as Apple Cider),” their lengthiest released track, with its upshifting and downshifting speeds (Wilson dominates on the bluesy downtempo sections) and Krupa’s propulsive work in the out-chorus; “Tea for Two,” in which Hampton and Krupa vie to be Goodman’s most loquacious accompanist, Hampton filling any space he can find, while Krupa plays swaggering press rolls. In the last chorus, they spiral around each other (see also how Krupa ends Wilson’s solo with rapid-fire tom hits, punctuated by a muted kick beat); “Runnin’ Wild” opens with a quick-step Krupa shuffle and builds up a head of steam—Hampton’s solo is the heat turned off for a chorus. It closes with Goodman driving the rest of the quartet ahead of him, its last thirty seconds a marvel.

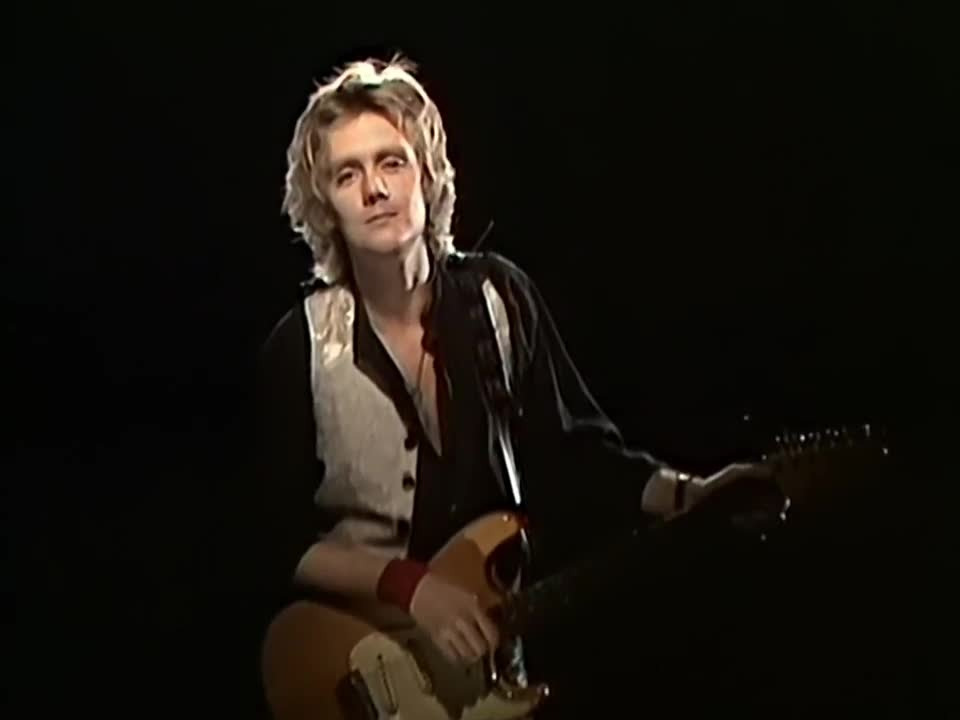

At the turn of July-August 1937 in Hollywood (while they were filming Hollywood Hotel), the Quartet cut some of their finest performances. A take on George Gershwin’s “The Man I Love,” cut weeks after his death, has Hampton as church accompanist (quoting “Rhapsody in Blue”), Goodman in a funereal tone, Wilson as eulogist, Krupa as sexton. There’s Krupa’s unusual, vivid hi-hat accents on “Handful of Keys,” in which Wilson seizes a classic Fats Waller piece for his own ends, and Krupa’s thundering toms on “Smiles,” where Goodman and Hampton keep a banter going throughout. Gershwin’s “Liza,” with Wilson’s Debussy-esque intro and his counterpoint during Goodman and Hampton’s solos.

And “Avalon,” an old Al Jolson hit (greatly written by Vincent Rose, who nicked from Puccini’s Tosca for the lead melody; Puccini’s publishers sued and won). The Quartet did two takes. The second was the release, while the first is a rare document of the Quartet in workshop mode. In the first take, you hear the Quartet taking risks in timing, phrasing, harmonies, with Wilson in particular out on the wire. The released take is tighter, more streamlined, with Goodman, in his solo, expanding on melodies and hooks he’d scattered through the first take.

There’s a slackening in the Quartet’s last 1937 sessions, as if they’ve gone as far as they can envisage, along with signs of growing commercial pressures—see their takes on hokey “Continental” pop hits, some inspired (“Vieni, Vieni, Vieni”), some wearying (“Bei Mir Bist Du Schoen”). Better was “Ding Dong Daddy (from Dumas),” another Quartet track that lays the ground for bebop—see Goodman’s chromatic passages in his solo, which, as Schoenberg noted, “creates a melodic/tonal ambiguity that Wilson exploits.”

The Break

Gene had excitement. If he gained a little speed, so what? Better than sitting on your ass just getting by.

Goodman

Goodman was a martinet with his players. If you hit a bum note on stage, you got “The Ray”: a withering stare. His iciness had thickened with success (Down Beat headline from February 1937: “Is Benny Goodman’s Head Swollen?”). Where Krupa was “our spark plug, our showman,” as pianist Jess Stacy said, Goodman reminded kids, and some of his musicians, of their chemistry teacher. “Benny built a little cellophane barrier between himself and his audience,” the saxophonist Jerry Jerome said. “They had to take him as he was and like it.”

So Goodman solos got modest applause while Krupa’s cheers were such (especially given the white-hot popularity of “Sing Sing Sing,” his showcase number) that the band sometimes had to pause, with Goodman sitting cross-legged on the stage, until the crowd settled down. Tempos also were a slugfest. Helen Ward said that Goodman, wagging an index finger, could kick off songs too slowly or too fast, while Krupa could also rush if he got caught up in a song (John Hammond thought Krupa’s playing had deteriorated with fame, that he was getting too showy).

Benny didn’t like all the crazy antics and sensationalism that he felt were overshadowing the real music. Gene thought that the craziness was just basic showmanship. Although I tended to agree with Gene, I stayed out of it.

Hampton

By early 1938, Krupa and Goodman were arguing on stage (“you’re the ‘king of swing,’ let’s hear you swing!” Krupa once retorted) and in Philadelphia, an ugly bout ended with Krupa reportedly saying “eat some shit, Pops!” and quitting after the show. All at once, the Quartet was over. Hampton filled in on drums until March. By leaving, Krupa helped to fully integrate the Goodman Orchestra.

Opuses In Our Flats: 1938-1939

Dave Tough at work in the basement [William Gottlieb]

Dave Tough was a slight man, weighing little over a hundred pounds. He’d gone to Ernest Hemingway’s high school and had accompanied Langston Hughes and Kenneth Rexroth during poetry readings. He moved to Paris, wrote limericks with F. Scott Fitzgerald, got married, split from his wife, returned to America a wreck. In the early Thirties he was on the street in Chicago. “He looked like a bum and he hung out with bums,” Jess Stacy said. “He’d go along Randolph Street and panhandle, then he’d buy canned heat and strain off the alcohol and drink it.” Marrying Casey Majors, a dancer, helped him to sober up and he drummed for Bunny Berigan and Tommy Dorsey.

Goodman hired him in March 1938 to replace Krupa, giving the band a drummer so devoted to support that he’d solo only under duress. “No drummer could match his intensity,” Ed Shaughnessy said. “He had the widest tempo, the broadest time sense…he was always at the center of the beat, even though he gave the impression he was laid back.”

Gifted at tuning, Tough ensured that his kick beats wouldn’t swallow bass notes. Instead, as recalled Sid Weiss, Goodman’s bassist at the time, when Weiss played a note, Tough’s kick “would go through the note and amplify it…the way the pedal struck the drum, it was just absolutely perfect.” To achieve this, Tough polished his kick pedal with a damp cloth and left the drum head “so loose it almost had wrinkles in it,” Shaughnessy said. “He tuned his snare and tom toms the same way, so that they were almost flabby.” (This was the polar opposite of a few years before, when Krupa had subsumed the bass playing of Goodman’s brother, Harry; likely with good intentions.) Tough was also a cymbals devotee, using a Chinese cymbal for gauzy backdrops, thirteen-inch hi-hats for accompaniment, and a mini-cymbal to dart into a bar or two.

So: an ideal contrast for Krupa’s replacement in the Quartet. On “Sugar,” he accompanies Wilson’s solo mostly with kick drum beats; on “Sweet Lorraine,” the first Quartet recording that he made, his brushwork sounds like rustled tissue paper. Its centerpiece is Wilson’s solo: a ballad for two hands, one consoling, one yearning, which Tough embroiders with subtle, intricate cymbal patterns.

And “Dizzy Spells,” one of the high triumphs of the Quartet recordings. It moves like a bullet train, each player locked in, each sounding improbably cool and precise at a tempo at which one single bum note could derail everything. Goodman’s playing in his solo is flat-out incredible, and he needles Hampton in the latter’s solo; Tough and Wilson achieve a mind-meld in Wilson’s chorus (listen to how Tough shifts in the latter half from a pounding beat to a more ironic accenting).

Goodman soon grew frustrated with Tough, recipient of assorted Rays on stage. While he’d resented Krupa’s popularity, Goodman still wanted a big, loud, charismatic drummer. Whereas “Davey was subtle. Subtlety was not for Benny’s band,” Mel Powell recalled. A beleaguered Tough lost weight he didn’t have, started drinking again. In late October 1938, Goodman fired him, kicking off a long period of transitory, unhappy drummers, one of whom, Nick Fatool, “wanted to cut [Goodman’s] head off with a cymbal” by the end of his brief tenure, as per Jerry Jerome. “I think maybe he just didn’t like drummers,” said the trumpeter Chris Griffin of Goodman.

Not long before, the Quartet had cut a last session with Tough. With Krupa’s departure, it was as if a tacit compact had broken in the group and Hampton, freed of his extrovert rival on the drums, became more dominant a force. There was “Blues in Your Flat”/”Blues in My Flat,” one of the rare Quartet sides apparently fully improvised in the studio, with Hampton in control—he (barely) rewrote Lil Armstrong’s “Lonesome Blues” for the lead melody and recycled some lines from his own “Vibraphone Blues.” Another in this line was “Opus 1/2,” a Hampton/Goodman original on which Tough sounds like he’s playing castanets and typewriter.

John Hammond, Goodman, Charlie Christian in 1940 [Whitten Collection]

In March 1939, Wilson left to form his own jazz orchestra (it disbanded in little more than a year—“it didn’t have mass appeal,” Wilson later said). His last Quartet recordings were cut at the end of 1938. In another sign that the old structure was crumbling, this edition of the Quartet had a bassist (John Kirby) and Hampton on drums (still a delight—see “I Cried for You” and “I Know That You Know”). A post-Wilson session in April 1939, with Jess Stacy on piano and Buddy Schutz on drums, resulted in one last side: “Opus 3/4.”

You can hear in the latter the Quartet about to fledge into Goodman’s last great innovation—his Sextet, a chamber supergroup whose members included, at times, Hampton, Cootie Williams, Jo Jones, Count Basie, Fletcher Henderson, and most of all, the young electric guitarist Charlie Christian. The Sextet lies beyond the realm of this already far-too-sprawling essay: listen to “Flying Home” and “Rose Room” and “Grand Slam” (the latter helping invent rock ‘n’ roll in April 1940) to get a taste of its brilliance.

The Sextet closed down in summer 1941, when Christian’s poor health forced to him to quit the band; he died not long afterward. Hampton had left the year before. Goodman gave him his blessing and some cash to start up his own band, if taking a percentage of their grosses (Hampton: “he was a businessman.”) By early 1941, no one who had played with Goodman at his Carnegie Hall show in January 1938 was still with him. A Benny Goodman Quartet persisted for years as a stage creation, and on an inspired 1942 disc, but it was an imposter, if one that still swung.

Into the Woods

I became famous with the Benny Goodman Quartet. But it was time to move on.

Hampton

Goodman, Krupa, and Wilson, among others in the Goodman Orchestra, 1952 (Fred Palumbo)

Within weeks of leaving the Benny Goodman Orchestra, Gene Krupa got a record contract and set up a band, soon booked for a year’s worth of shows. “Why be a clerk when you can run your own store?” he told Burt Korall. If Goodman was acerbic about them (“I don’t think Gene ever had really a great band…he had to lead, the drummer was a leader. And that’s a difficult thing”), the Krupa Orchestra, especially once Roy Eldridge and Anita O’Day signed on (see their hepcat dialogue “Let Me Off Uptown”), was a prime jazz group of the early Forties, backing Barbara Stanwyck in Howard Hawks’ Ball of Fire. Then, disaster.

NYT accounts of Krupa’s arrest (21 January 1943) and conviction (1 July), the latter printed above an ad for a Goodman residency

In a scenario which a few rock musicians would find familiar, Krupa had a hanger-on desperate to do a favor for him. This was his valet, who, according to one story, bought marijuana cigarettes for Krupa or, as per another account, decided to bring Krupa some pot from his dressing room without Krupa asking him to. At any rate, the authorities swept in, eager to bust Krupa, who was flashy, played jazz, and wasn’t in uniform during wartime: a patron saint of juvenile delinquents.

Krupa was arrested and tried, pled guilty to a lesser charge in the hopes of avoiding a felony count, got a ninety-day jail sentence, which was interrupted by a second trial for the felony charge (contributing to the delinquency of a minor). (“The ridiculous thing was that I was such a boozer I never thought about grass. I’d take grass, and it would put me to sleep,” Krupa later said.) He lost a Coca-Cola sponsorship; his band fell apart; he was evicted from his New York office, its furnishings dumped onto the street. Goodman, one of the few who’d visited him in prison, hired Krupa when the latter got out in late 1943, so as to get Krupa back in the spotlight.

Krupa in New York, 1946 (William Gottlieb)

In the mid-Forties, Krupa put together a new band: a “modern” jazz orchestra whose players included Red Rodney and Charlie Kennedy and for which Gerry Mulligan wrote arrangements. Krupa struggled with bebop-style drumming, having trouble shifting his focus from kick and snare to ride cymbals—bop’s emphasis was on the pulse, disdaining the bowling-alley-crash fills that Krupa had made his name on. Eventually, as per Mel Lewis, “he caught on. His bass drumming became lighter—not a hell of a lot, but a little. He started playing time on ride cymbals and dropping bombs…on the right beats, on four and three, not on one so much. He’d listen.” (See, among others, “What’s This” (1945, with Dave Lambert on vocals), and “Up an Atom” (1947)).

Eventually, the group was spent, breaking up in 1951. Krupa joined Norman Granz’s Jazz at the Philharmonic troupe, was a regular on TV, did drum duels with Buddy Rich. He became a swing kid memory for a generation aging in suburbia.

After Teddy Wilson’s big band split up (Al Hall, its bassist: “everybody kept saying we sounded too white”), he played at the Cafe Society in Sheridan Square in the Village, leading a house band, earning $100 a week. His was a life of steady, occasionally desperate work. Barney Josephson, who ran Cafe Society, recalled that “Teddy had been through a bunch of wives, and he’s had kids with each one of them. He has a lot of alimony to pay all around, so he needs money all the time.”

He’d back everyone from Lena Horne to Zero Mostel at Cafe Society; he worked for CBS in the Fifties, played Caribbean resorts, played New York, played Europe, taught private lessons and at Juilliard. He spent more time touring Japan during one stretch of the early Seventies than in Boston, where he lived. It all evened out, he said. “You’re never around anybody long enough to say, well, I want to get away from you. Everywhere you go, you’re glad to see the people, when you come home, when you go away.”

Wilson, Arthur Godfrey, Billie Holiday, 1947 (CBS Photo Archive)

When Gary Giddins caught Wilson at the NYC club Fat Tuesday’s in 1980, he wrote that while Wilson’s “talent has not dwindled, the radical aspects of his style have not hardened into mannerisms, and he’s never compromised commercially,” his repertoire was the same as it had been forty years before. It was as if Wilson was on strike against the passage of time. At Fat Tuesday’s that night, a table of drunk tourists sang the opening lines of every well-worn song Wilson played; he sat there and took it, seemingly content to be a legendary cocktail pianist.

Yet each night, when he played “Tea for Two” or “Sweet Lorraine” yet again, with some sauced accounts manager mumblesinging the refrains, Wilson looked within the songs for something that he hadn’t found yet.

“You never play the same way,” he once told Josephson.

Some nights you can play [the piano] and on other nights it absolutely defies you…Some nights it plays itself, and that keeps you interested, too…The notes are coming out just like you want them. It’s like it’s talking. It’s saying something. It’s hard to figure. You’re just at the mercy of it.

Lionel Hampton at the Aquarium, 1946 (Gottlieb)

Hampton was always going to do fine. All but born on stage, he loved being there; he’d resonate as if he was one of his vibraphone bars. Milt Jackson, in the Modern Jazz Quartet, would pick up where Hampton had left off, in terms of expanding the potential of vibraphone improvisation. Hampton was happy to be a bandleader, to bounce from drums to piano to vibes to microphone, to be his own hype man. Of the Goodman Quartet, he was the most fluent in jump blues and early R&B, which he helped create—see “Flying Home” and “Rag Mop.”

On tour, Hampton found that “a lot of time we got bookings because the managers thought I was white,” he wrote. “I’d played with Benny Goodman…but they clearly hadn’t seen any pictures of the Benny Goodman Quartet.” He was a sunny integrationist. When he found a ballroom where the floor was divided to keep the races apart, “I cut the ropes down more than once—they weren’t going to have segregated dancing where I was playing.”

“I’d like to think that I helped bring black music to white audiences,” he added. “I know I exposed thousands and thousands of white people to some of the most talented black musicians who ever lived.” Dexter Gordon was in his band for a time; Dinah Washington got her break with him (“that girl was so poor she was raggedy. And she was dark—the light-skinned girls got all the attention in those days,” he wrote about seeing Washington for the first time), as did teenage Quincy Jones, in the early Fifties.

Hampton said he recorded a rock ‘n’ roll album in 1946, Rock and Roll Rhythm. It was “too cacophonous” for Decca, who allegedly shelved the tapes. “I was ahead of my time on that. Rock and roll wouldn’t be big for another ten years.” There’s no other mention I’ve ever found of this never-released album, apart from a paragraph in Hampton’s autobiography. Maybe it’s the Rosetta Stone of rock ‘n’ roll; maybe it’s another great Hampton tall tale. It does feel like Lionel Hampton could have invented physics at some point, too.

He always stayed in the black groove, Hampton said. “You knew my band was black just from listening to it.” A soul-infused piece like “Greasy Greens,” from the mid-Sixties, showed that, as back when he started with Les Hite thirty years earlier, his core philosophy was to “get people to dance, to have a good time, clap their hands.”

Between November 1940 and the recording ban that began in August 1942, Benny Goodman used sixty-five musicians in his sessions, including eleven drummers—it got to the point where he’d fly in a new player and fire him after the first gig. He was losing out, in personnel and record sales, to such rivals as Artie Shaw (“excellent clarinetist…the only trouble was his band was a copy of my band”), Glenn Miller, and Goodman’s former trumpeter Harry James.

Yet he was still developing musically, thanks to one of his new arrangers, Eddie Sauter, who had a taste for dissonance, richly-textured instrumentation (see “The Man I Love,” from 1940, in which bass clarinet and baritone sax serve as contrary basslines), and unusual modulations. And to Peggy Lee, whose twenty-month stint with Goodman resulted in some of the most beautiful recordings he ever made. “My Old Flame,” which Lee sings abstractedly, drifting through the piece “like a slow-moving distant cloud in the sky” (Schuller). The hushed, cryptic reserve of her phrasings in “The Way You Look Tonight,” where she works against Mel Powell’s celeste as if she’s another keyboard line; “Where Or When,” in which she seems to burnish each syllable in moonlight.

In poor health at times (in 1940, he’d had surgery for a ruptured disk, a procedure that he’d never fully recover from, needing painkillers and a horse collar to get through gigs), Goodman started taking flak from the music press (Jazz Session: “an uncreative riffster trying desperately to copy even the poorest of Negro musicians and failing miserably”; Metronome: “his arrangements smack of the mid-’30s”; Down Beat: “he seems to want the blandest possible changes behind him…it bothers him to hear an unfamiliar voicing”).

Even John Hammond, in Music and Rhythm in June 1942, blasted him for “no longer [being] an innovator or a musical radical. Instead of forming popular tastes he is bowing down to them and following the path laid down by his imitators.” (This was a few months after Goodman had married Hammond’s sister, Alice; make of that what you will.)

These were too harsh a critique. Goodman’s ambitions were now more centered on classical music. He’d played with the Coolidge String Quartet and commissioned, among other pieces, Bartok’s Contrasts, Copland’s Concerto for Clarinet, and Morton Gould’s Derivations for Solo Clarinet and Dance Band. (“It’s a sense of, well, growing up I guess,” Goodman said. “What are you going to do, go out and play ‘Lady Be Good’ again forever and ever?”) And Goodman’s bebop-influenced group at the end of the Forties made some inspired recordings—see “Undercurrent Blues” and “Stealin’ Apples,” the latter with Fats Navarro.

Goodman’s increasing aesthetic conservatism was more owed to commercial realities. The “avant-garde” stuff didn’t sell, he griped, while the 1950 LP release of his twelve-year-old Carnegie Hall concert moved a million copies by decade’s end. In 1953, Goodman spouted to the New York Times that “bop…is a lot of noise, the wrong kind of noise. They can’t play their horns. No tone, no phrasing, no technique…the damn monotony of it got to me.” (Of his own foray into bop, he called it “an experiment…leave it with that.”) The pianist Marian McPartland, who toured with Goodman in 1963, recalled him being sour about how she voiced chords. “I guess I was slipping in flatted fifths and Benny didn’t care for those kind of extended modern harmonies.”

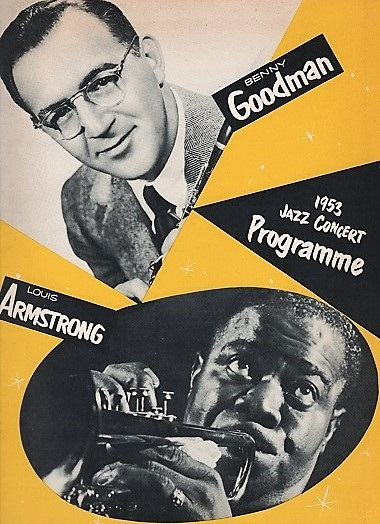

Yet nostalgia had its perils, too. A joint tour in 1953 with Louis Armstrong proved disastrous—the two quarreled and Armstrong would lengthen his sets to eat into Goodman’s time on stage. Goodman, visibly drunk at some shows, collapsed in Boston, having to be put into an oxygen tent. Krupa took over as co-bandleader for the tour: it became a success.

Together Again

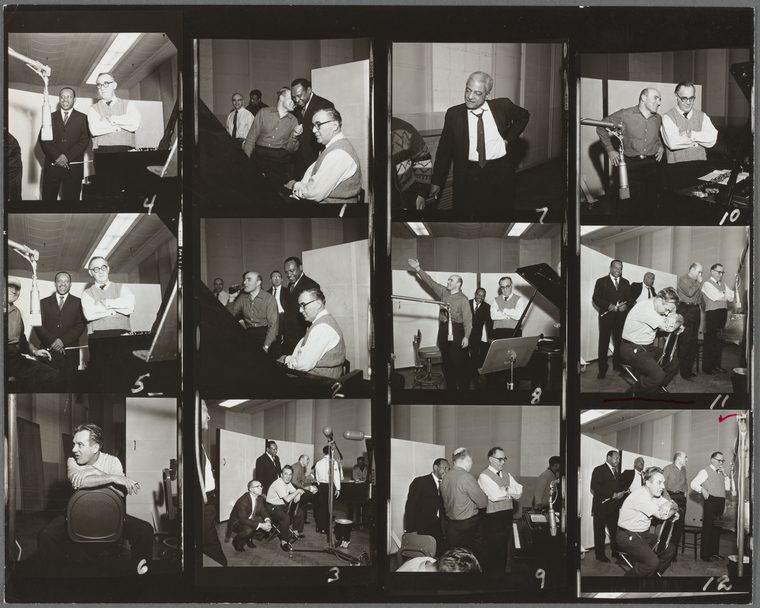

During the sessions for Together Again, 1963 [William Randolph]

The Benny Goodman Quartet first reunited in 1954 for an NAACP benefit, (Goodman had continued to work with Krupa and Wilson sporadically before then) and then to play themselves in The Benny Goodman Story, a clunky biopic starring Steve Allen (it did produce another great take on “Avalon”). Goodman had drifted into becoming the typical jazz elder of the time—small group sets that got respectful New Yorker “Talk of the Town” write-ups; Waldorf-Astoria residencies; State Department-sponsored tours of foreign countries.

Quartet, 1955

In 1963, he thought to reunite the Quartet in the studio: after all, they’d never made a proper album. George Avakian, chosen to produce, was wary of doing a homage to past glories. So he was relieved to learn Goodman “had already decided to record fresh material they hadn’t played to death in the old days.” An initial session (13 February 1963) found the Quartet working through “Love Sends a Little Gift of Roses” (a World War One-era John McCormack ballad), Kurt Weill’s “September Song” and Gerry Mulligan’s “Bernie’s Tune.”

It was a lost session (“rather pedestrian,” Avakian recalled): everyone was nervous, uncomfortable with the songs, took ages between takes. As Avakian told George Firestone: “Once or twice there was a bit of roughness between Benny and Hampton when Benny wouldn’t accept Hampton’s suggestions about a background figure.” Goodman, assuming he’d be the boss as in the old days, found that instead he was sitting in a room with three other thick-egoed middle-aged men, each of whom had had run a band for years.

William Randolph contact sheet: Quartet and Avakian recording Together Again (NYPL)

They tried again, some months later, on 26 August 1963. It was a miracle day, with seven of the album’s ten tracks cut during it. If the selections were less adventurous (most dated from the Thirties, including a revisit to “Runnin’ Wild” and the Sextet classic “Seven Come Eleven”), the group sounded tight, with a strong repartee. Together Again (released in early 1964), if far from a masterwork, is livelier and fresher than it could have been. It’s a happy opportunity to hear the Quartet recorded well, with stereo mixing—you can make out Krupa’s cymbal work in sparkling detail, or how Wilson’s left and right hands navigate though a song.

In the fall of 1972, Goodman was asked by Timex to bring the Quartet back together for a TV special taped at Lincoln Center. This kicked off two years of Quartet reunions on stage, a period that Goodman looked back on with regret:

I don’t think [the reunions] recaptured anything. You can’t expect people to come together and pick up right where they left off. That’s impossible. In 1937, it was the Benny Goodman Quartet. In 1973, we were all leaders. Leaders don’t want to become sidemen again, do they? The concerts went well to the extent that we were all good musicians and played well together. But it wasn’t like it was before.

Goodbye

The day before the Quartet played Carnegie Hall in July 1973, they rehearsed at CBS Studios on 52nd Street and let in the press to watch them at work. The New York Times‘ Tom Buckley described Hampton, wearing “a reckless suit of magenta plaid,” as appearing worried and distracted, which someone in the room said was because “Lionel’s a big businessman now. He’s opening a big housing project in Harlem this Saturday.”

They went through “After You’ve Gone” and “Handful of Keys,” “My Melancholy Baby” and “Avalon.” Krupa said the rehearsal was “to see if I can hack it.” He’d gotten out of the hospital not long before. He’d had a benign form of leukemia for years, requiring routine blood transfusions. Apart from some hesitations on tom fills, Krupa sounded well enough. At five o’clock, Wilson stood up to leave. “Come on, we’ve got time for a few more,” Goodman said. Wilson said no, he had to be “way the hell out in Jersey by seven, and you’re going to make me late.” Goodman thought about contesting the point, then acceded, taking apart his clarinet and drying each piece with a cloth.

“This would have been only starting for us twenty-five or thirty years ago,” he rued. “We used to play five or six shows a day at a place like the Paramount and maybe double somewhere else.” A TV reporter asked what he thought of rock music. Not much. “I hate all that amplification. I don’t know what it’s all about. I’m glad we don’t have to do anything but play the way we want to.”

They played Carnegie Hall and, not long afterward, Saratoga Springs, on 18 August 1973. The end at last: Krupa died two months later, at sixty-four.

One of the last photographs of the Quartet (with Slam Stewart on bass), NYC, 28 July 1973 [Jack Manning]

Wilson and Goodman would work together for another decade, though the strains in their relationship had only grown. They weren’t speaking at times, with the saxophonist Loren Schoenberg once roped in to be their negotiator backstage (“Loren, ask if Teddy if he wants to play ‘China Boy’…”Tell Benny I don’t play ‘China Boy’ anymore”). Goodman thought Wilson had dried up; Wilson considered working with Goodman a necessary evil (“the man is the same today as he was in 1936. You just have to learn to ask for enough money to make it worth your while…these jobs allow me to play with a class of musician I can’t afford to hire myself,” he once told the bassist Bill Crow).

The last time the two played together was for a Goodman TV special taped on 7 October 1985, at the Marriott Marquis. Wilson, who’d been diagnosed with stomach cancer, came out for “The Man I Love” and “But Not For Me.”

Goodman, in chronic pain, had long kept his appearances limited–a duet with George Benson on “Seven Come Eleven” on a 1978 TV special, for instance. While he admitted “I don’t have the stamina I used to,” he’d still practice daily and said he’d never retire: it was work or the grave.

In 1986, he gave an interview to Tower Records’ Pulse! where he bristled at the statement that his music was passe: “contemporary, shmentemporary—it doesn’t mean a goddam thing.” But his last shows were crumbling affairs. He had to be led off stage, near-delirious with the flu, at the University of Michigan. At Wolf Trap, in Arlington, Virginia, he found it so hard to breathe that he was reduced to pantomime by the final numbers, moving his fingers along his clarinet without playing a note. It was his last time before an audience.

Less than a week after that, on 13 June 1986, Carol Phillips, the companion of his last years, found Goodman holding his clarinet, sitting on a sofa in his Manhattan apartment, and about to die from a heart attack. He’d been rehearsing, with Brahms and Mozart pieces on the music stand. “Benny did not believe in an afterlife,” she told Firestone. “He felt you’re here and that’s it.”

Teddy Wilson died half a month later, in a New Britain, Connecticut, hospital.

Hampton, eldest of the Quartet, would be the last of them. In the late Eighties, he wrote his memoir, with James Haskins. It opens as one of the great American autobiographies—a rich picture of the Jim Crow South and Jazz Age Chicago—and becomes a garrulous collection of awards acceptances and I-met-him-whens. Always a politician, he hardened into the role in his old age. Hampton had worked to elect Nixon, was a proud Reagan supporter, devoted a couple pages of his book to complain about sex in movies.

In 1997, a halogen lamp caused a fire in his apartment. It nearly killed him—the blaze consumed his belongings (as many of his master tapes would be claimed by the Universal Studios fire a decade later). Yet two days later, in a borrowed suit, he accepted an award from Bill Clinton. If he’d lost everything he’d carried with him, Hampton nearly lived forever. His death, in 2002, is provisional. Like his father, he may yet pop up somewhere, if only to surprise us.

End of a session: Hollywood, 26 August 1936. The Goodman Quartet does a nondescript blues of Hampton’s. It sounds as if it was cut at some ebb hour, the air rich with smoke (it was probably around four in the afternoon).

Wilson’s solo is an exhausted man trying to fit his key into a lock.

Hampton leans towards the microphone, with a theatrical groan. If the blues was whiskey, babe, I would stay drunk all the time. An arch delivery. All…of the time.

Play it Mister Goodman! Play it a long, long time! Goodman, flattered, does a strut. Wilson takes a few bars; Hampton’s eye is on him, too. Oh play it Mister Wilson! Play that long, long time. Krupa shifts in. Now when Mister Krupa beats those riffs….he don’t let you down! Yeah.

Hampton closes it out like he’s notarizing a deed. Goodman looks at the engineer. All good? Click: a day, a world, disappears.

Booker T. (for Taliaferro) Jones, born in Memphis in 1944, was a musical prodigy. He started on oboe in fourth grade (“a C instrument: that’s how I got into the school band,” he recalled to Terry Gross), soon taking up clarinet (“a B-flat instrument!”), soon again piano (“another C instrument—it helped me to get the structure of music in my mind”). He learned trombone, saxophone and bass; by fourteen, he was playing bass at nightclubs on Beale Street and in West Memphis. “The bandleaders had to come to my house [and] persuade my mom and dad that they were okay,” Jones told Stax historian Robert Gordon (he once was called out of algebra class to play in a recording session.)

Booker T. (for Taliaferro) Jones, born in Memphis in 1944, was a musical prodigy. He started on oboe in fourth grade (“a C instrument: that’s how I got into the school band,” he recalled to Terry Gross), soon taking up clarinet (“a B-flat instrument!”), soon again piano (“another C instrument—it helped me to get the structure of music in my mind”). He learned trombone, saxophone and bass; by fourteen, he was playing bass at nightclubs on Beale Street and in West Memphis. “The bandleaders had to come to my house [and] persuade my mom and dad that they were okay,” Jones told Stax historian Robert Gordon (he once was called out of algebra class to play in a recording session.) off. And, man, that thing went off at 20 tempos!”).

off. And, man, that thing went off at 20 tempos!”). “We would leave our job and go to the colored clubs and listen to those bands play. That’s really how we got started,” he said in 1967. As Jonathan Gould wrote, “whites could move with relative impunity through the black locales of Memphis…their presence not appreciated but tolerated.” (The reverse obviously wasn’t the case.) He took up guitar, soon favoring the Fender Telecaster. An early influence was Lowman Pauling, guitarist/composer of The “5” Royales, and

“We would leave our job and go to the colored clubs and listen to those bands play. That’s really how we got started,” he said in 1967. As Jonathan Gould wrote, “whites could move with relative impunity through the black locales of Memphis…their presence not appreciated but tolerated.” (The reverse obviously wasn’t the case.) He took up guitar, soon favoring the Fender Telecaster. An early influence was Lowman Pauling, guitarist/composer of The “5” Royales, and  Steinberg was nearing thirty and had a deep musical lineage—his father was a Beale Street pianist; his sister sang with Fats Waller; his brothers played with Lionel Hampton; his niece was a Memphis DJ. He’d come up in jazz, favored the upright bass and had a brisk, walking-centered style.

Steinberg was nearing thirty and had a deep musical lineage—his father was a Beale Street pianist; his sister sang with Fats Waller; his brothers played with Lionel Hampton; his niece was a Memphis DJ. He’d come up in jazz, favored the upright bass and had a brisk, walking-centered style. The bassman swap happened while Booker T. and the MG’s were a provisional concept. Jones was at college in Indiana from fall 1962 through spring 1966—some piano and organ parts on MG’s singles of the period are by another Stax mainstay, Isaac Hayes. The band was a foremost a studio outfit (live, “Booker T. and the MG’s” were whoever got on stage under that name—David Porter sometimes sang with them). For a long time, they were that group that did “Green Onions.”

The bassman swap happened while Booker T. and the MG’s were a provisional concept. Jones was at college in Indiana from fall 1962 through spring 1966—some piano and organ parts on MG’s singles of the period are by another Stax mainstay, Isaac Hayes. The band was a foremost a studio outfit (live, “Booker T. and the MG’s” were whoever got on stage under that name—David Porter sometimes sang with them). For a long time, they were that group that did “Green Onions.”

Booker T.’s opening organ riff (song transposed to Gm)

Booker T.’s opening organ riff (song transposed to Gm)