Pope John XXIII, born Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli in Bergamo, Italy, in November 1881. Ordained to the priesthood on August 10, 1904. Consecrated Bishop, March 1925, titular Archbishop of Areopolis. November 1934 transferred to the Apostolic Delegation to Turkey and Greece, and appointed Apostolic Administrator of the Apostolic Vicariate of Istanbul.

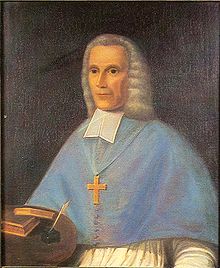

Mgr. Roncalli, far right, Papal Nuncio to Istanbul, with some of the clergy. (c. late 1930s early 1940s)

The following notes were recorded by Mgr Roncalli who was on Retreat between 25 November - 1 December 1940, at Terapia on the Bosporus, at the Villa of the Sisters of Our Lady of Sion.

Monday evening, 25 November, 1940.

Yesterday our Holy Father Pius XII invited the whole

world to join him in the sorrowful singing of the Litany of the Saints and the

penitential psalms, the Miserere.

We

all from the West and from the East, joined with him in his petition.

In

my solitary retreat I am making the Spiritual Exercises, as the Holy Father

himself is doing just now in the Vatican, and in this way I begin the sixtieth

year of my humble life. For myself and for the good of all, I think I cannot do

better than return to the penitential psalm (Psalm 50/51) dividing the twenty

verses into four for each day and making them the subject of religious

meditation.

As a

starting point I am using Father Segneri’s exposition of the Miserere, but with

considerable freedom of inspiration and applications.

To

understand the profound meaning of the Psalm, I find it a great help to bear in

mind the figure of the royal prophet himself and the circumstances of his

repentance and grief. It is a king who

has fallen; it is a king who rises again.

First day, Tuesday, 26 November.

VERSE 1: ‘Have mercy on me, O God, according to thy

great mercy.’

1.. The mourning of the nations. This cry reaches my ears from every part of

Europe and beyond. The murderous war

which is being waged on the ground, on the seas and in the air, is truly a

vindication of divine justice because the sacred laws governing human society

have been have been transgressed and violated.

It has been asserted, and is still being asserted, that God is bound to

preserve this or that country, or grant it invulnerability and final victory,

because of the righteous people who live there or because of the good that they

do. We forget that although in a certain

sense God has made the nations, he has left the constitution of states to the

free decisions of men. To all He has

made clear the rules which govern human society; they are all to be found in

the Gospel. But He has not given any guarantee of special and privileged

assistance, except to the race of believers, that is, to Holy Church as such.

And even His assistance to His Church, although it preserves her from final

defeat, does not guarantee her immunity from trials and persecutions.

The

law of life, alike for the souls of men and for nations, lays down principles

of justice and universal harmony and the limits to be set to the use of wealth,

enjoyments and worldly power. When this

law is violated, terrible and merciless sanctions come automatically into

action. No state can escape. To each its hour. War is one of the most

tremendous sanctions. It is willed not by God but by men, nations and states,

through their representatives.

Earthquakes, floods, famines, and pestilences are applications of the

blind laws of nature, blind because nature herself has neither intelligence nor

freedom. War instead is desired by men, deliberately, in defiance of the most

sacred laws. That is what makes it so evil. He who instigates war and foments

it is always the ‘Prince of this world’, who has nothing to do with Christ, the

‘Prince of peace’.

And while the war rages, the

people can only turn to the Miserere and beg for the Lord’s mercy, that it may

outweigh his justice and with a great outpouring of grace bring the powerful

men of this world to their senses and persuade them to make peace.

2. The mourning of my own soul. What is happening in the world on a grand

scale is reproduced on a small scale in every man’s soul, is reproduced in

mine. Only the grace of God has

prevented me being eaten up with malice. There are certain sins which may be

called typical; this sin of David’s, the sins of St Peter and St Augustine. But

what might I not have done myself, if the Lord's hand had not held me back? For

small failings the most perfect saints underwent long and harsh penances. So

many, even in our own times, have lived only to make atonement; and there are

souls whose lives, even today, are one long expiation of their own sins, of the

sins of the world. And I, in all ages of my life more or less a sinner, should

I not spend my time mourning? Cardinal Federico’s famous reply is still so

eloquent and moving: ‘I did not ask for praises, which make me tremble: what I

know of myself is enough to confound me.’

Far

from seeking consolation by comparing myself with others, I should make the

Miserere for my own sins my most familiar prayer. The thought that I am a priest and Bishop and

therefore especially dedicated to the conversion of sinners and the remission

of sins should add all the more anguish to my feelings of grief, sadness and tears,

as St Ignatius says. What is the meaning

of all these flagellations, or having oneself set on the bare ground, or on

ashes, to die, if not the priestly soul’s continual plea for mercy, and his

constant longing to be a sacrificial victim for his own sins and the sins of

the world?

3. The great mercy. It is not just ordinary mercy that is needed

here. The burden of social and personal wickedness is so grave that an ordinary

gesture of love does not suffice for forgiveness. So we invoke the great mercy.

This is proportionate to the greatness of God.

4. ‘For according to His greatness, so also is

His mercy’(Eccles. 2:23) It is well said that our sins are the seat of divine

mercy. It is even better said that God’s most beautiful name and title is this:

mercy. This must inspire us with a great hope amidst our tears. ‘Yet mercy

triumphs over judgement.’(James 2:13) This seems too much to hope for. But it

cannot be too much if the whole mystery of the Redemption hinges on this: the

exercise of mercy is to be a portent of predestination and of salvation, ‘Have

mercy on me, O God, according to thy great mercy.’

VERSE II: ‘And according to the multitude of thy tender

mercies blot out my iniquity.’

The

Lord is said to be 'merciful and gracious’.

His mercy is not simply a feeling of the heart; it is an abundance of

gifts.

When

we consider how many graces are poured into the sinner’s soul along with God’s

forgiveness, we feel ashamed. These are: the loving remission of our offence;

the new infusion of sanctifying grace, given as to a friend, as to a son: the

reintegration of the gifts, habits and virtues associated with the grace; the

restitution of our right to heaven; the restoration of the merits we had earned

before our sin; the increase of grace which this forgiveness adds to former

graces; the increase of gifts which grow in proportion to the growth of grace

just as the rays of the sun increase as it rises, and the rivulets are wider as

the fountain overflows.

VERSE III: ‘Wash me

yet more from my iniquity, and cleanse me from my sin’: holy confession.

Three verbs: to blot out, to

wash and to cleanse, in this order.

First the iniquity must be blotted out, then well washed, that is, every

slightest attachment to it is removed; finally the cleansing, which means

conceiving an implacable hatred for sin and doing things which are contrary to

it, that is making acts of humility, meekness, mortification, etc., according

to the diversity of the sins These three operations follow one another but to

God alone belongs the first. To God, in cooperation with the soul, the second

and the third: the washing and the cleansing. Let us, poor sinners, do our

duty: repent, and with the Lord’s help, wash and cleanse ourselves. We are sure

that the Lord will do the first, the blotting out; this is prompt and

immediate. And so we must believe it to be, without doubts or hesitations. ‘I

believe in the forgiveness of sins.’ The two processes which depend on our

cooperation need time, progress, effort. Therefore we say: ‘Wash me yet more

……. And cleanse me.’

This

mysterious process of our purification is perfectly accomplished in holy

confession, through the intervention of the blood of Christ which washes and

cleanses us. The power of the divine blood, applied to the soul, acts

progressively, from one confession to another. ‘Yet more’ and ever more. Hence the importance of

confession in itself, with the words of absolution, and of the custom of

frequent confession for persons of a spiritual profession, such as priests and

Bishops. How easy it is for mere routine to take the place of true devotion in

our weekly confessions! Here is a good way of drawing the best out of this

precious and divine exercise: to think

of Christ, who, according to St Paul, was created by God to be ‘our wisdom, our

righteousness, sanctification and

redemption’ (1 Cor. 1:30)

So,

when I confess, I must beg Jesus first of all to be my wisdom, helping me to

make a calm, precise, detailed examination of my sins and of their gravity, so

that I may feel sincere sorrow for them. Then, that he may be my justice, so

that I may present myself to my confessor as to my judge and accuse myself

sincerely and sorrowfully. May he be also my perfect sanctification when I bow

my head to receive absolution from the

hand of the priest, by whose gesture is restored or increased sanctifying grace. Finally, that he may be my redemption

as I perform that meagre penance which is set me instead of the great penalty I

deserve: a meagre penance indeed, but a rich atonement because it is united

with the sacrament to the blood of Christ, which intercedes and atones and

washes and cleanses, for me and with me.

This

‘wash me yet more’ must remain the sacred motto of my ordinary

confessions. These confessions are the surest

criteria by which to judge my spiritual progress.

VERSE IV: ‘For I

know my iniquity and my sin is ever before me.’

The

advice of the ancient philosopher: ‘know thyself’, was already a good foundation for an

honest and worthy life. It served for the ordinary exercise of humility, which

is the prime virtue of great men. For the Christian, for the ecclesiastic, the

thought of being a sinner, does not by any means signify that we must lose

heart, but it must mean confident and habitual trust in the Lord Jesus who has

redeemed and forgiven us; it means a keen sense of respect for our fellow men

and for all men’s souls and a safeguard against the danger of becoming proud of

our achievements. If we stay in the cell of the penitent sinner, deep in our

heart, it will be not only a refuge for the soul which has found its own true

self, and with its true self calm in decision and action, but also a fire by

which zeal for the souls of men is kept more brightly lit, with pure intentions

and a mind free from pre-occupations about success, which is extraneous to our

apostolate.

David

needed the shock of the prophet’s voice saying: ‘You are the man.’ But

afterwards his sin is always there, always before his eyes, an ever-present

warning: ‘My sin is always before me.’

Father

Segneri wisely points out that it is not necessary to remember the exact form

of every single sin, which would be neither profitable nor edifying, but it is

well to bear in mind the memory of past failings as a warning, as an incitement

to holy fear and zeal for souls. How

often the thought of sins and sinners recurs in the liturgy! This is even more

true of the Eastern than of the Latin liturgy: but it is well expressed in

both: ‘My sin is always before me’, just as the sins of men were before Jesus

in his agony in the garden of Gethsemane, as they were before Peter at the

height of his authority as Supreme Pontiff; before Paul in the glory of his apostolate,

and before Augustine in the splendour of his great learning and episcopal

sanctity.

I

pity those unhappy men who, instead of keeping their sin before them, hide it

behind their backs! They will never be free from past or future sins. (to be continued)

Ack. ‘Pope John

XXIII -

Journal of a Soul’ – translated by Dorothy White. Published by Four Square Books, New English

Library, 1966.